The fatal triangle: Returning from a nightmarish Acapulco vacation in March 1958, Lana Turner and Johnny Stompanato arrive in Los Angeles, where they are met by Turner’s daughter, Cheryl Crane.

Fifty years ago this April, a young man from Woodstock, Illinois, named Johnny Stompanato was stabbed to death in the bedroom of his lover, the movie goddess Lana Turner. Stompanato was a minor hoodlum and notorious lothario, and news accounts eviscerated his character in the media frenzy after his death. Now a writer, also from Woodstock, follows a fading trail to find how a small-town Midwesterner landed at the heart of one of Hollywood’s most enduring scandals.

A gracious mapled square dominates the center of Woodstock, Illinois, the former farm town in the flat landscape about 60 miles northwest of Chicago. Though strip malls in the area have eaten into businesses in the heart of town, and residential development has gobbled the circling cornfields, the square itself retains its 19th-century charm, with a bandstand, a filigreed spring house, and a sturdy monument to Civil War soldiers.

An 1889 opera house, a charming relic of another civic age, holds down the square’s south side. As a teenager, Orson Welles, who had been deposited by his father in the excellent (now long gone) Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, put on shows at the opera house that helped launch his lifelong passion. On the square’s west side stands an antique courthouse and jail where the union activist Eugene Debs was held in 1895—far from the riotous city—for his role in the Pullman Strike. Today, the jail has been turned into a lively restaurant, and the neighboring courthouse contains galleries, shops, and the Dick Tracy museum, an attraction (slated to close in June) honoring the late Chester Gould, the comic strip’s creator and a longtime Woodstock resident.

Welles, Debs, Gould. Those names shine with as much luster as Woodstock has offered the world over the years, though if you go north from the square about a hundred yards on Main Street and look up at a fading pinkish storefront on the east side, you can see the ghostly outlines of another, more infamous name associated with the town: Stompanato.

Fifty years ago on an April Good Friday, Johnny Stompanato, the on-and-off lover of the movie star Lana Turner, was stabbed to death in her Beverly Hills bedroom by Turner’s 14-year-old daughter, Cheryl Crane. The slaying set off a worldwide sensation, and it remains one of Hollywood’s most notorious scandals.

I grew up in Woodstock, 20 years or so behind Johnny Stompanato, whose parents owned a barbershop and beauty salon on Main Street. On the Monday after his death, I remember seeing the famous photo on the front page of the Woodstock Daily Sentinel. (The caption began: “Woodstock got into the news plenty over the weekend. . . .”) The three principals in the scandal had greeted photographers just weeks earlier—Lana, platinum and taut; handsome Johnny, his silk shirt unbuttoned to reveal a large medal dangling in a field of dark chest hair; and Cheryl, looking hopelessly plain and gawky against the glowing human specimens beside her. To an 11-year-old heartlander, the picture offered a perfect expression of the imagined Hollywood nuclear family, shortly before detonation.

At the time, Woodstock was still largely rural, still basically disconnected from Chicago. I wondered even then where this son of the small-town Midwest had come up with the ambition that would land him in Hollywood in the arms of a goddess. Over the years, even as I’ve come to realize that Hollywood is a repository of small-town refugees, I’ve tried to imagine what ignited Johnny—or Jack, as he was known in Woodstock.

His story, as it came out after his death, got told in a toxic confluence of tabloid reporting, police assertions, and spinning by the Hollywood establishment. The portrait appalled: hoodlum, blackmailer, bully, gigolo. But the reports were largely uncorroborated and many of them quoted each other in a kind of echo-chamber effect. I remained curious over the years, so recently I went back looking for a true picture of my fellow son of Woodstock. I suppose I secretly hoped to find evidence that an aggressive but basically decent man had been terribly libeled.

That doesn’t turn out to be the case. From this distance, it’s almost impossible to sort the facts, but in particular the accounts—largely unconfirmed but consistent—of his mistreatment of women are ugly and disheartening. Johnny could certainly charm, but he belongs to the predatory genus of that familiar archetype, the American dreamer. As Erlene Wille, who worked in his father’s shop and knew Johnny’s pleasing side, says in her gentle way, “I liked John, but I also don’t know that he was a man that you could trust.”

Still, for a villainous footnote in pop culture history, the Johnny Stompanato who emerges from a bit of research led an exotic, even mysterious life, certainly given his small-town roots and early death at 32. He served under fire as a marine in the Pacific theatre, hung out at Hollywood’s swankiest lounges, befriended the flamboyant West Coast mobster Mickey Cohen. Not even counting the affair with Lana, Johnny passed through a rich and beautiful assortment of women, including three wives. Indeed, it’s hard to separate Johnny’s ambition from his romantic escapades. Early on, he developed that passion that stirs some small-town folks to get out, move on, move up. And women were his way.

* * *

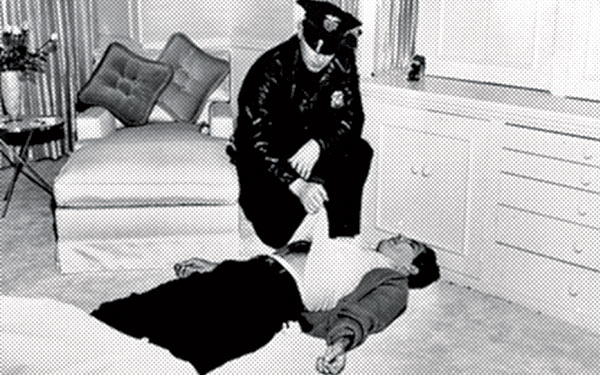

Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

A cop examines Stompanato’s corpse.

The Pink Bedroom

Though the slaying of Johnny Stompanato follows a rich tradition of Hollywood mayhem, it continues to intrigue because of the persistent speculation that Lana killed Johnny and, to save her career, arranged for Cheryl to take the blame. In fact, the homicide bristled with the sorts of anomalies that stoke the American love of conspiracy. To begin with, How could Johnny let it happen? He was an ex-marine with a résumé that, by some accounts, placed him as a bodyguard to Mickey Cohen; Cheryl was barely out of children’s clothes. Given a delay by Lana in calling the authorities and a strangely feckless coroner’s inquest, it’s hardly a wonder that the Stompanato family always thought there was more to the story than came out.

Still, only three people witnessed what happened in the pink bedroom on that Good Friday night, and the two who survived stayed basically consistent in their stories, from the immediate aftermath through their autobiographies decades later. And by everyone’s account, the whole evening’s tableau of happenstance, rage, violence, and tragedy has the messy illogic of real life, trampled by hysteria.

Johnny and Lana had been lovers for months, though afterwards Lana maintained that he had grown increasingly possessive and threatening and that she had been trying to break off the affair. Lana had just moved into a new, furnished house in Beverly Hills, and on the day of the killing, Cheryl, her troubled only child, was home for the holiday from her private school up the coast. Lana’s friend and makeup man, Del Armstrong, had dropped in for a visit and brought with him C. William Brooks II, a Hawaii businessman. In an odd coincidence, Brooks had known Johnny 17 years before when they were cadets at Kemper Military School, in Boonville, Missouri. Johnny hardly seemed eager for the mini reunion and left quickly.

“He had a great fear of me talking to her,” Brooks says today. It’s little wonder. Johnny had told Lana he was 43. Here was Brooks, 34, who revealed to Lana that he had been a year ahead of Johnny in school.

For an actress who, at 38, was already self-conscious about her age, the thought of being squired by a younger man was terrifying. After the guests left and Johnny returned, Lana berated him for lying about his age. She insisted that the affair was over, and he had to leave. He yelled at her for drinking too much and refused to go.

The argument drifted upstairs, where Johnny followed Lana into Cheryl’s room. In her 1988 autobiography, Detour (written with help from the veteran entertainment reporter Cliff Jahr), Cheryl says that now, for the first time, she saw Johnny’s rage: “[H]is neck veins stood out and he breathed from one side of his mouth. He hunched his shoulders as though he were going to pull out a pair of six-shooters, while the hands at his sides clenched and writhed like a snake’s tail in death.”

The fight moved to Lana’s bedroom. According to Lana’s testimony at the inquest, Johnny shook her violently and told her he would never let her go, that “I would have to do any and everything he told me, or he would cut my face or cripple me and if it went beyond that he would kill me and my daughter and my mother.”

Cheryl heard the terrible threats. She knew of her mother’s aversion to calling the police—bad publicity, of course. In a panic, she says, she ran downstairs. In the kitchen, she seized a knife with an eight-inch blade and dashed back upstairs, intending, she says, to scare Johnny. More screaming in the bedroom. Cheryl pounded on the door. It opened suddenly. “Mother stood there, her hand on the knob,” Cheryl says in Detour. “He was coming at her from behind, his arm raised to strike. I took a step forward and lifted the weapon. He ran on the blade. It went in. In! For three ghastly heartbeats our bodies fused. He looked straight at me, unblinking. ‘My God, Cheryl, what have you done?'”

In her testimony, Lana said the whole thing happened so fast, “I truthfully thought she had hit him in the stomach with her fist.” Johnny staggered and fell onto the pink carpet, “making dreadful sounds in his throat, gasping, terrible sounds,” Lana said. He hadn’t been about to hit her—his arm was raised because he was carrying a jacket and shirt on a hanger.

Lana got a towel for the wound and then phoned her mother, who lived nearby and who called a doctor. Lana summoned the lawyer Jerry Geisler, a famous Hollywood Mr. Fixit. They tried to resuscitate Johnny and the doctor gave him a shot of adrenaline. The Stompanato family later questioned why it took Lana and her people so long—at least 30 minutes—to summon the police. But the authorities said it wouldn’t have made any difference. Johnny Stompanato died within five minutes. On his wrist, he wore a silver bracelet inscribed in Spanish: “Papa Johnny, sweet love of mine, when you use this remember it is a piece of my heart that will always be with you. . . . With all my love, Lanita.”

Mickey Cohen identified the body at the morgue and called Woodstock with the details. Carmine Stompanato, a 45-year-old barber in the family shop, flew out to Los Angeles to bring his younger brother home.

* * *

Photograph: Los Angeles Times/AP

Her finest performance: A week after the slaying, a distraught Turner testifies at the coroner’s inquest looking into Stompanato’s death. The jury would deliverate for less than half and hour before delivering its verdict.

Farm Town

When Johnny Stompanato was growing up in Woodstock in the 1920s and ’30s, the Stompanatos were one of the few Italian families in the town of 6,000 or so. Johnny’s parents, John Sr. and Carmela, were born in Italy, but met and married in Brooklyn. They moved in 1916 to Woodstock, where John took a job in a barbershop and Carmela worked as a seamstress. John founded a beauty and barbershop in 1929, and in 1949 he opened a real-estate business under the same roof. Outside of town, he had a small farm with dairy cattle.

Before Johnny, the Stompanatos had three children, Grace, Teresa, and Carmine, and the family lived in a big house on Blakeley Avenue a few blocks southwest of the high school. Though the town had a flourishing Catholic church, the family belonged to the Presbyterian Church.

The girls were in high school and Carmine was 12 when Carmela delivered John Jr. by cesarean section on October 19, 1925. Six days later, she died of peritonitis in the Woodstock hospital. Both local dailies ran front-page articles. The American described her as the “favorite Italian mother of Woodstock.” The Sentinel called the death “very very sad.”

Though there’s no way to know the impact on the infant of the absence of his mother, in later life Johnny showed a remarkably consistent inclination to attach himself to older women. In any case, four years later, John Sr. took a new wife, a Wisconsin woman named Verena Frietag, and she and young Johnny enjoyed a warm relationship. Years later, Erlene Wille recalls, “he said, ‘I used to get confused, whether she was my real mother and [my father] was my stepfather, or vice versa.'”

Woodstock kids in those days had the run of the pretty little town. Johnny played marbles in front of the courthouse, games in the leafy square. Casimer Polizzi, a younger schoolmate from another Italian family in town, says Johnny had a bit of a swagger early on. “He was my protector—nobody fooled around with me as long as I was with Jack. He was tough, but he liked people.” This was less than a decade after Al Capone ruled Chicago, and given Johnny’s Italian name, dark complexion, and curly black hair, Polizzi recalls, kids used to say he was connected to the Mafia.

Johnny may have been happy to encourage the notion, but people who knew the Woodstock Stompanatos say it was utterly false. Wille, who worked in the barbershop for six or seven years in the late 1940s and early ’50s, never saw or heard a hint of anything to do with the mob. “They were nice, good people,” she says.

Johnny’s peers remember a boy who was rambunctious, but not a serious troublemaker. “Jack was a devil—he got away with everything,” recalls Alice Nulle, who knew him from church. By the time Johnny hit his teens, however, he had become a handful at home. He put in a year at Woodstock Community High School, and then in 1941 his parents enrolled him at Kemper. The institution (closed since 2002) had a reputation as one of the outstanding military schools in the country.

Johnny’s grades put him in the bottom half of the class, and teachers complained he didn’t work to capacity. “Better than average intelligence and a quick learner when he wishes, but interested in little but salacious literature and women,” says a note on his record. (Kemper’s records are at the Western Historical Manuscript Collection at the University of Missouri at Columbia.)

* * *

By then Johnny was six feet tall, 180 pounds, with dark wavy hair. He tooted saxophone in the band and wrestled and swam to little distinction. His interests lay elsewhere. “He was a good-looking scamp and he liked his fun,” recalls Richard Heisler, who also came from Woodstock and knew Johnny at Kemper. “The girls all went for him.”

Johnny’s roommate one year was a former New Trier High School student named Hugh Krampe, who went on to fame as the actor Hugh O’Brian, star of the 1950s TV show The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp. “He was a pretty amazing person in many ways,” O’Brian says of Johnny today. “Unfortunately, not all of it was put to use in the right direction.”

O’Brian recalls that Kemper occasionally ordered up surprise five- to ten-mile marches early in the morning. It seemed as if Johnny had always checked into the infirmary those mornings and hence avoided the hikes. The other boys suspected that he was having an affair with a nurse, who would alert him to the surprise drills.

Like kids in Woodstock, the Kemper boys gossiped that Johnny’s family had links to the mob. Many were “country club boys,” as the widow of one classmate puts it, and gave Johnny a wide berth. “He kinda liked that reputation,” Bill Brooks recalls.

In his second and final year, Johnny seemed to make a little academic progress and teachers began to cite his college potential. By then, though, the United States was well into the war. Johnny enlisted as a private in the marines, joining the 1st Marine Division, one of the military’s legendary fighting units.

By the spring of 1944 he was in the Pacific, moving from island to island as a clerk in a service battalion. During the war, the Sentinel sent copies of the paper to local boys overseas and asked them to send letters back. On August 10, 1944, the paper printed a note from Johnny written on a Japanese post card. “We have a wonderful bunch of fellows in our outfit and everything is pretty much O.K. Of course we would rather be home but that is besides the point . . . ,” he wrote. “But when the outfit isn’t in a combat zone we have movies most every night. It is a grand thing, the motion picture industry is doing by seending [sic] the movies over here to us.”

Five weeks later, the 1st Marine Division invaded Peleliu, a tiny island held by the Japanese. “Peleliu was a horribly costly battle,” says Len Hayes, a retired marine colonel who is executive director of the 1st Marine Division Association and who examined Johnny’s military records. “[Stompanato] was in a service unit, but he would have seen action, artillery fire and mortar fire. At Peleliu, everybody came under fire.”

The next April, Johnny participated in the capture of Okinawa. By the time the island had been subdued, however, he was up to trouble—sneaking into the officers’ mess wearing someone else’s lieutenant’s stripes. “That’s just the kind of guy he was,” says Alice Nulle, whose late sister, a nurse, was on Okinawa with Johnny. “Nobody was going to tell him what to do.”

* * *

Johnny took his discharge in March 1946 in the Far East. He claimed later on that he ran a string of nightclubs in China, though it’s likely he was just polishing his résumé for his cronies in Hollywood. By another account, he was working as a civilian for the U.S. government. In any case, one day the handsome ex-marine wandered into a dress shop in Tientsin and met a petite, pretty saleswoman named Sara Utush, who had grown up in China with her immigrant Turkish parents. The attraction was immediate. Johnny converted to Islam to marry Sara that May. Not long afterwards, he brought her back to Woodstock. She told Erlene Wille that she didn’t realize until they were filling out papers for the return that he was only 20, five years her junior. She said she knew that wasn’t good, but by then they were married.

After marine combat and China, Johnny grew restless in Woodstock, where he drove a bread truck and worked in an auto-parts factory. Sara got pregnant, but Johnny left for California not long after the baby, John III, was born. Sara had to work nights, sewing in a factory. Charla Johansen Pierce, whose mother baby-sat the child, remembers that Sara sang to the little boy to put him to sleep. “And then she had to go to work,” Pierce says.

Later, after Johnny’s death, Sara spoke graciously of her ex-husband. “He had a good heart, you know,” she told a reporter, “but he just never grew up.”

* * *

Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

“Like a kid brother”: Stompanato (left) with his mobster mentor, Mickey Cohen, 1950.

Mickey’s Boy

Johnny Stompanato had been thinking about Hollywood since before he left his wife and child behind. He spoke vaguely of knowing some marines from Los Angeles, and at one point he urged an old schoolmate to join him on a foray there. The schoolmate turned him down, but Johnny found a traveling companion well outside the Woodstock norm—Charles A. Hubbard, a titled heir to an English fortune with whom Johnny danced an odd minuet for several years.

Like so much else about Johnny’s West Coast years, details are sketchy. By one account, Johnny met Sir Charles at a Chicago restaurant. Hubbard was headed cross-country, and Johnny went along. The two may have roomed together for a time in L.A. Over several years, Johnny later told the Internal Revenue Service, he “borrowed” $65,000 from Hubbard. The sum apparently was never paid back, and this led to unconfirmed suggestions that Johnny held something over his British companion.

Johnny soon fell in with the man who would color and shape the last decade of his life. Mickey Cohen had been a thug and likely a killer in his younger days, but by the late 1940s he was running gambling operations and vice rackets out of his clothing store on Santa Monica Boulevard. By various accounts, East Coast mobsters had instructed him to keep an eye on West Coast business, which meant, principally, the activities of Bugsy Siegel, a Hollywood figure who had helped pioneer casinos in Las Vegas. A sniper assassinated Siegel at his girlfriend’s home in 1947, leaving Cohen as the mob kingpin on his side of the country. The Siegel murder has never been solved.

Mickey Cohen made other mobsters anxious. A puggish ex-boxer, he had grown into a peacock who hung out with reporters. Whether his flamboyance provoked his colleagues or he simply got tangled in the usual underworld disputes, he was targeted for several shootings and two home bombings in the late 1940s and early ’50s in the so-called Sunset Strip War.

It’s not clear how Johnny hooked up with Cohen—by one account, they met at Cohen’s haberdashery; by another, Johnny took a job as a bouncer at a Cohen club. But by July 1949 (according to Hollywood’s Celebrity Gangster, a Cohen bio by Brad Lewis), when gunmen ambushed Cohen and his cronies as they left a Sunset Strip nightspot, Johnny was in the entourage—and escaped unharmed.

The newspapers and cops insisted on referring to Johnny as Cohen’s bodyguard, but that seems to overstate the case. Cohen scoffs at the notion in his 1975 autobiography, Mickey Cohen: In My Own Words. “There was no get-up about Johnny being a bodyguard at all,” Cohen says. “He didn’t have the kind of vicious makeup whatsoever for those kind of things. In fact, although he was a marine hero, when it come to violence or gun activities outside a war situation, Johnny would shy away completely.”

Cohen recounts how his crew terrorized Johnny during the Sunset Strip violence by putting black handprints on his garage door, supposedly an ancient sign that he had been marked for death. The henchmen were teasing and testing Johnny, and Cohen had to tell them to lay off.

In fact, Cohen genuinely seemed to enjoy the handsome younger man. “He was like a kid brother,” Cohen writes. Johnny hung out at Cohen’s house, and he often served as Cohen’s driver. Occasionally, the two traveled cross-country together. Because of Cohen’s notoriety, they were chased away by cops in cities along the way, including Chicago. “We don’t want your scar tissue scattered around our city,” deputy chief of detectives John T. O’Malley told Cohen. Perhaps on that same trip, Johnny dropped Cohen somewhere and drove the mobster’s big black car to Woodstock. The town’s hugely fat police chief, Emery “Tiny” Hansman, ordered Johnny to get the thing off the streets—Woodstock didn’t want any trouble, either.

Johnny’s police record and FBI file suggest he was a lackey for Cohen—running errands, handling cash, making purchases, perhaps operating small businesses used to launder money. Johnny carried a gun at least occasionally, and confidential informants told the FBI that he collected protection money from spots that had jukeboxes ($1 per week) and picked up proceeds from the numbers racket. In that period, he sometimes used an alias (Johnny Valentine, Thommie Valen) and he was arrested six times, usually for vagrancy (part of a police effort to “dehoodlumize” the strip, as the authorities put it). None of the charges stuck.

* * *

By far the darkest aspect of Johnny’s dealings with Cohen—one that is featured in rumor and allegations—involves sex and blackmail. Stories circulated that Cohen ran an extortion operation that preyed on Hollywood stars, acquiring tapes and photos of compromising encounters. When Johnny appeared on the scene, the stories go, he became Cohen’s magnet for aspiring actresses and established stars. “This was a guy who Cohen had seduce targeted women—anyone who was on her way up or down,” says Ted Schwarz, the author of Hollywood Confidential: How the Studios Beat the Mob at Their Own Game. Schwarz says his chief source for the blackmail charge is an ex-cop turned investigator named Fred Otash, whose credibility suffers somewhat from his association in that era with Confidential magazine, a notorious scandal sheet.

The authorities certainly believed that Johnny had used his charms to take advantage of women. Immediately after his death, Beverly Hills police chief Clinton H. Anderson called him “a gigolo type character,” and the newspapers quoted a Los Angeles police report that accused him of preying on rich women (the report apparently contained no details). Johnny’s old roommate Hugh O’Brian, who ran into him occasionally in Hollywood, says he heard various accounts that suggested the accusations were true. “He carried a date book and always had 8 to 15 women in it, all of them married,” O’Brian says. “He would see them at a club and somehow get their phone number. Then he would call—’I saw you last night at Ciro’s. I got your number because I think you’re the most beautiful woman in the world.’ They’d ask, ‘Who’s this?’ And he’d tell them he can’t say. Then he’d hang up. He’d do it two or three times and lure them in.”

Eventually, Johnny and his target would meet and the encounters often led to sex, O’Brian continues. After a few trysts, Johnny would tell his victim he needed a small loan, $150 or so. She would give it to him. Soon enough, he would ask for big money—”$5,000 or so,” O’Brian says. “They’d say, ‘That’s too much.’ He’d say, ‘If I don’t get this money, your husband will get pictures.’ Usually, the women came through.”

A loose piece of evidence that turned up after Johnny’s death supports O’Brian’s account: Chief Anderson said he had found incriminating negatives in a little wood box that Johnny owned. “The pictures would have been a gold mine for a blackmailer,” said Anderson. He added that the “picture collection verified information we already had.” The chief said he destroyed the film, and that was that.

According to Johnny’s FBI file, the Los Angeles Police Department long suspected him of being a pimp. Despite investigations, however, the LAPD never charged him. The file is thin on specifics, but one anonymous source provides a secondhand account from a woman who claimed Johnny had lured her into prostitution. The woman said he charmed her and she became infatuated. Then he borrowed money, which he didn’t repay. When he wanted more money, he suggested she quit her job and work as a call girl. She did, and Johnny arranged for another man to send her dates, at a minimum of $20 per. She estimated that she gave Johnny at least $5,000 of her earnings before quitting the game.

The shady financial manipulations echo a style of Johnny’s operation that is undisputed. After his death, authorities turned up a number of troubled transactions. A woman described by the papers as a “pretty, red-haired Mar Vista widow” acknowledged she had loaned him $8,150 to start a gift shop, a loan that was never repaid. “He needed the money to buy it and he came to me because he said he felt I was the only one he could talk to,” Doris Jean Cornell told reporters. “He was nothing but a gentleman toward me and there was no romantic interest whatsoever.”

Johnny’s effects also included several bankbooks and documents that seemed to indicate he had been married to a Rosemary Trimble, “the beautiful blond wife of a West Los Angeles physician,” as the Los Angeles Times put it. Mrs. Trimble said she and her husband knew Johnny while he was married to his third wife. “We played cards with them,” she said. “He seemed to be a very nice man at the time, but as far as being married to him—oh, no!”

In all, Johnny left a thick portfolio of unpaid obligations and other financial shenanigans, the sort of record that would have appalled his enterprising immigrant father. (For all the money that passed through Johnny’s hands, his estate totaled $274 at his death.) Erlene Wille thinks the family didn’t realize he was hanging out with the notorious Mickey Cohen until a picture of the two of them together appeared in Life magazine. She recalls that another barber in town ran down to the news depot and bought up all the copies to save the Stompanatos further embarrassment.

* * *

Photograph: AP

“John Steele”

|

|

With Cohen and his cronies, or on his own, Johnny gravitated to the nightspots along Sunset Strip, places that brought together money, glamour, and beauty. Hollywood offered Johnny a lush environment to flaunt his looks and charm. He “was running around with every broad in the movie industry,” Cohen writes. (In Detour, Cheryl recounts the gossip that Johnny was nicknamed “Oscar” because the size of his penis recalled the Academy Award statuette.)

In 1948, Johnny married the actress Helen Gilbert, whose slight career was shifting from movies to television. She was ten years older than he, and the marriage lasted just three months. Later, she reportedly testified, “Johnny had no means. I did what I could to support him.”

He had his eye on the stars. Chasing after Ava Gardner, Johnny apparently never got much beyond sharing drinks, but it was enough to infuriate her other suitor of the time, Frank Sinatra. In his book, Cohen reports that Sinatra asked him to get Johnny to stay away. Cohen says he told the singer: “I don’t mix in with no guys and their broads, Frank.”

Around 1950, Stompanato began surreptitiously courting the actress Janet Leigh, sending her flowers and records with a card signed “Johnny.” The two finally met and even visited together on a few occasions, but when Johnny finally revealed who he was and described his connections to the mob, Leigh sent him packing.

In 1953, Johnny broke his pattern and married a younger woman, Helene Stanley, an actress best known for playing Davy Crockett’s wife in the Disney TV show. The year before, in Woodstock for his father’s funeral, Johnny had invited Erlene Wille and her then husband to drop in if they ever vacationed in Los Angeles. In 1954, they did and looked Johnny up—just knocked on the door, as she tells it today. “He came to the door and said, ‘Oh, hi!’ as if we were his long-lost friends. I mean, he was so happy to see us.”

He was living with Helene Stanley and her parents, and he was raising parakeets in back. The Woodstock couple stayed at a nearby motel and joined Johnny and his wife at a lively party that night. At one point, Johnny confided to Wille that he wanted his young son, who was living with his mother in Indiana, to come out for a visit in the summer. “And I said I didn’t think it was a good idea—’He doesn’t even know you,'” Wille recalls. “And, oh, well, he didn’t see why not. He was his father!”

Wille befriended Helene Stanley and kept in touch by mail. A year or so later, Stanley revealed that the marriage was breaking up. “I wrote and I said, ‘I thought Johnny really loved you,'” Wille says, “and she wrote back and said, ‘He doesn’t; all he really cares about is what he can get out of me.'” They divorced in 1955.

* * *

Over the years, Johnny held down a series of legitimate jobs—or, at least, he claimed to: jeweler, car salesman, florist, pet shop owner. His last occupation was running the Myrtlewood Gift Shop, the place that had been generously funded by Doris Jean Cornell. Cheryl Crane worked one summer in the shop, and in her book she recalls it as a “puzzling operation,” with “some inexpensive pieces of crude pottery and wood carvings displayed as if they were art.” Johnny spent most of his time in the back on the phone, and part of Cheryl’s job was to “run to the post office with brown packages eight inches square. Judging by their size and weight, they probably weren’t pottery.”

He was spending less time with Cohen (who served time for tax evasion in the early 1950s), and Johnny occasionally left hints that he wanted to break away from the mob. Wille recalls that he came through Woodstock one time and told his family he was going to escape by leaving the country. He got as far as New York, and something or somebody turned him back. At home in California, he told Wille’s husband that he wasn’t “involved” at that point, but he carried a gun because, as she recalls, “there were always the little guys that were trying to make a name for themselves that were ready to shoot somebody like him who already had a name.”

By the time he met Lana Turner in the spring of 1957, Johnny increasingly entertained hopes of getting into the movie business. “[H]is dream was to become a motion picture producer,” writes Taylor Pero, who worked as the actress’s personal manager in the 1970s and later co-wrote the book Always Lana. Other accounts say Johnny even had a story in mind that he unsuccessfully urged Lana to option.

At 37, Lana’s Hollywood image as a ripe Sweater Girl was starting to fray, and her prospects of staying a bankable star seemed uncertain. She and her mother had moved to Los Angeles after her father, a gambling man, had been bludgeoned to death in San Francisco. As a teenager, Lana had been discovered at a soda shop, and throughout the 1940s and early 1950s she starred in 20 or so movies, notably as a sexually charged small-town wife in The Postman Always Rings Twice and a scorned and embittered movie actress in The Bad and the Beautiful. The summer after she met Johnny, she started work on Peyton Place, playing the mother of a troubled teenager. Her personal life was messy: She had already been through four husbands.

Johnny first courted her just the way he had approached Janet Leigh: with an outpouring of flowers and record albums, accompanied by a card signed, “John Steele.” In her autobiography, Lana says she raged at him when she finally learned, after they had started their affair, that he was really Johnny Stompanato, a Mickey Cohen associate. She hesitated to appear in public with him, fearing bad publicity. Still, she stayed with him as he lavished jewelry and a blanketing attention on her. He telephoned constantly, broke into her apartment and bedroom, told her she would never get away from him. Still, Lana admits she was hooked: “His consuming passion was strangely exciting,” she writes. But it wasn’t just the sex, which she calls “nothing special.” He could be thoughtful and caring, and she was weak and lonely.

Through the summer and fall of 1957, Johnny insinuated himself into Lana’s life. He gave Cheryl her summer job and bought the teenager a horse (Cohen later claimed to have paid for it). Some days, Cheryl and Johnny would go riding together in the hills above Los Angeles. “[There] were times I saw more of him than [my mother] did,” Cheryl writes in Detour. Cheryl was the daughter of Lana’s second husband, Stephen Crane. The girl had endured what she calls an “appalling” childhood—scrambling for her mother’s attention and suffering sexual abuse at the hands of her mother’s fourth husband, the actor Lex Barker. She had become hard to handle, and Lana worried about the crowd she hung out with. Johnny came up with the idea of sending her to live with his stepmother in quiet little Woodstock, and with Lana’s approval broached the idea. Verena Stompanato eventually said no—she thought she was too old to take in a troubled teenager, Wille recalls.

In her book, Cheryl remembers her outings with Johnny as “halcyon” and calls him her “sidekick.” Though people later speculated that Johnny, too, had abused her, Cheryl says no—”[H]e took pains to stay at arm’s length,” perhaps aware of her previous torment.

It’s tempting to think of Johnny at about this time as a kind of pernicious Jay Gatsby, almost within reach of the alluring green light at the end of the pier—life with a genuine star, a place for himself in the movie business, a path carrying him beyond the tawdry fame of being one of Mickey Cohen’s boys. But a better literary parallel probably comes from Budd Schulberg’s 1941 Hollywood novel, What Makes Sammy Run? Another ambitious son of earnest immigrants, Sammy Glick scammed and wormed his way to success in the movie business, shamelessly using and discarding people as he went.

* * *

Photograph: AP Photo/Stewart

|

|

At the end of Schulberg’s book, Sammy Glick is still on top, if alone. Johnny’s demise started as the summer of 1957 wore on and Lana began to have doubts about her mysterious boyfriend. In her autobiography, she tells a horrific story of his escalating anger and violence as she tried to curtail and ultimately end their affair. That fall, “an escape hatch seemed to open” when she flew to England to star with Sean Connery in Another Time, Another Place. But then she got lonely in cold, damp London and sent Johnny a ticket. “Our reunion was a joyful one and for a while John showed only his loving, docile side,” she writes. Soon he got bored, however, and insisted on coming to the studio. Their arguments built until one night he choked her so violently she had trouble talking and filming was disrupted. Her friend Del Armstrong was in London and arranged to have him deported.

When the movie wrapped, she left for Acapulco, planning a long rest. Her plane stopped in Copenhagen, and to her astonishment and dismay, she says, he met her at the airport and accompanied her to Mexico. She describes their stay at Villa Vera in Acapulco as a nightmare of tantrums and fights. He would never let her alone. After an iguana invaded her suite, the hotel’s proprietor gave him a gun and he used it to taunt and threaten her. “If you’re not going to be with me, you aren’t going to be with anyone else,” she says he told her.

Another escape hatch opened when she got word that she had been nominated for a best actress Oscar for Peyton Place. They cut short the vacation and flew back to Los Angeles, finding Cheryl, Lana’s mother, and an eager press corps at the airport. Johnny “seemed to be basking in the limelight,” Lana writes.

She refused to take him to the Academy Awards ceremony. He complained bitterly, and late that night when she got back to her bungalow at the Bel Air Hotel (having lost the Oscar to Joanne Woodward in The Three Faces of Eve), he was waiting and beat her viciously. Still, she didn’t try to get away from him or notify the police. Why? She writes that she was afraid. He had made repeated threats—he’d kill her or disfigure her face. He would kill her mother and Cheryl. He would use his mob connections to get the job done. “And then, too, there was the publicity,” Lana admits in the book. The newspapers would go to town if she went to the police, and her career would evaporate. “I was trapped, helpless because of my fear,” she writes.

Around that time, Lana’s mother, Mildred Turner, told the Beverly Hills police chief that her daughter was scared of Johnny and needed protection. Chief Anderson said there was nothing he could do unless Lana herself came to him. That didn’t happen, and a week later, during another bitter fight, Johnny ran into Cheryl’s knife.

In the immediate aftermath, Lana gave the authorities her account of being trapped and threatened. A few days later, Mickey Cohen deflated that bubble by giving the newspapers copies of letters Lana had sent Johnny from Europe. In her book, Lana calls them “too sentimental,” but that hardly describes the gushing endearments she showered on her lover: “Please keep well, because I need you so, and so you’ll always be strong and able to caress me, hold me, tenderly at first then crush me into your very own being,” she wrote in October from London. “[N]o matter what, it must be with me!!!”

Johnny apparently had a gift for gush, too. In another letter, Lana writes, “So many precious things you told me, described to me, each beautiful and intimate detail of our love, our hopes, our dreams, our sex and longings—My God, how you could write and when near me, make most of those dreams come to life and throb with the realness of you and me and us.”

In fairness to Lana, some passages in the later letters suggest that she was trying to pull away from him when she went to Acapulco—or, at least, she wanted to spend time alone to decide what to do. But Lana had been acting since she was 16; her letters and her behavior strongly suggest that she didn’t know what she felt—that she knew little of true passion beyond the romantic gestures, the purple words, the overheated outbursts.

I think a good case can be made that Lana and Johnny had a kind of folie à deux—a mutual delusion that each nourished alone and encouraged in the other. She vacillated between longing and fear. He swung between hope and fury. The lovers were so charged with misguided and misunderstood emotion that together they were almost bound to ignite a tragedy.

A week after the slaying a Los Angeles coroner’s jury held an inquest into the case. From this distance, the proceedings seem ludicrously thin. Among other things, the questioning of Lana was gentle and Cheryl never testified, appearing only through the statement she had given police the night of the killing. The jury quickly came back with a verdict of justifiable homicide. Observers wickedly called Lana’s trembling, weeping testimony her greatest performance ever.

* * *

Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

The starcrossed couple share a close moment at a Hollywood club in September 1957.

Taps

In Woodstock mythology, Johnny Stompanato’s funeral features endless lines of black cars, gangs of swarthy mobsters, troops of undercover officers. Contemporary reports indicate an event far quieter than that. Around 75 friends and family, including Johnny’s first wife, Sara, gathered at the small Merwin chapel. The Reverend Cecil C. Urch of the Presbyterian church told the mourners, “Our purpose . . . is not to praise John Stompanato, but to give comfort and consolation to those who remain.” Johnny lay in an open coffin, dressed in a tuxedo and ruffled shirt.

A larger crowd proceeded to Oakland Cemetery, accompanied by Woodstock’s 22-man American Legion color guard. The legionnaires fired three volleys and blew taps. Johnny was buried in the family plot, beside the graves of his mother and father. His stepmother, Verena, stood by bereft. “Johnny was the only child that she had; she didn’t have any children of her own,” says Erlene Wille. “And it was very sad.”

Mickey Cohen had announced that he would pay for Johnny’s funeral, but he couldn’t attend himself because he was on trial in Los Angeles for punching out a waiter. He came to pay his respects about a month later. Art Petacque of the Sun-Times caught up with him in Chicago at the Sands Motel on North Sheridan, where a squad car kept watch outside. Johnny “never did a bad thing in his life,” Cohen said. “Whatever he did for me was legitimate—I was always in legitimate business as well as in the rackets.” Cohen argued that Johnny should be pitied. “He was like a little baby, like a young kid. He got rushed into a falsely glamorous life too fast.”

The next day, Cohen drove his new pink Cadillac to Woodstock. He put flowers on Johnny’s grave and took Carmine and Verena to dinner at the Elks Club. Later, Carmine told Woodstock’s police chief, Tiny Hansman, that the coffin Johnny arrived in from Los Angeles was cheap and too small. The family had to get a new one before they could bury him. Carmine added that he was going to reimburse whoever had bought the cheap casket—the family didn’t want to owe anyone anything.

* * *

Despite the finding of the coroner’s jury, the Stompanato family had trouble believing the accounts given by Lana and Cheryl. “I don’t have any desire to prosecute [Cheryl],” Carmine said at one point. “I just want the truth to come out.” In late April, the family sued Lana for $750,000 on behalf of Johnny’s son. They built their case on the claim that Lana had negligently failed to control her daughter, but in fact they seemed to be searching for information about what happened that night. The suit kicked around the California courts for a few years and at one point the famed lawyer Melvin Belli represented the boy. In 1961, the parties settled with a $20,000 payment.

Just a year after the slaying, Lana scored a Hollywood success in Imitation of Life, playing another mother of a problem teenager. Her career puttered on for several decades beyond that and then she became increasingly reclusive. In 1995, she died of throat cancer at 74.

Cheryl couldn’t escape her unhappy adolescence. Though she was removed only briefly from her family’s custody because of the homicide, later troubles landed her in reform school and an asylum. As a woman, however, she straightened up and found success as a real-estate agent. In her book, she writes of her longtime, loving partnership with another woman, a relationship that continues to this day. (In an e-mail, Cheryl said she had nothing to add to the facts in her book.)

Verena and Carmine Stompanato died years ago, and today the only Stompanato I could find in Woodstock is a retired schoolteacher who was married for a time to Carmine’s son, who is also now dead. The barbershop stayed open into the 1970s, then became the Stompanato Barber Shop Lounge before it finally closed. Today, the space is again a tavern, D. C. Cobb’s. I stopped in last summer, and the genial young man behind the bar had never heard of Johnny Stompanato.

As I gathered information, I wondered whether Johnny’s son, John III, might still be alive. He would be about 60 now, and I knew he had taken the name of his mother’s second husband, Ali Ibrahim, like her a Turkish immigrant. What had the son’s life been like? Had he escaped the notoriety that touched his family? Through an old Woodstock address book and some Internet sleuthing, I found John Ibrahim in California. Out of the blue, I called one day. He was understandably guarded, but as we were about to sign off on our first conversation, he asked me if I knew what day tomorrow was. I fumbled: An obscure religious holiday? The date of a big football game? I stared at my calendar. October 19th. The birthday of the father he had hardly known.

Last January I flew to California to visit John Ibrahim. He and his wife, Lilly, live in a modest over-55 community in a ranch house on a golf course in a flat, desert town east of Los Angeles. He is a handsome man who resembles his father, though he wears his graying hair short and he sports a trim salt-and-pepper beard. As we talk, he describes a productive life, with a close family. Ali Ibrahim adopted young John and raised him as his son. The two were close throughout the adoptive father’s life. Sara, John’s mother, is still alive and lives nearby. John himself has two children and five grandchildren. He served in the air force, then worked for years for the Defense Department, handling electrical systems on airplanes. Today, he is retired on disability, owing to lung damage from a career breathing in chemicals.

Only family and close friends know he is the son of Johnny Stompanato, and yet it’s clear that his natural father has often been in John’s thoughts. Sara sheltered the boy at Johnny’s death and didn’t let him go to the funeral, but John has read the newspaper clippings, the books. He doubts his father was as bad as portrayed. “How much do you believe in what you read?” he asks. Still, he has a theory about Johnny’s character: A baby boy, left motherless in his first years, and a loving family tries to compensate. “He was spoiled,” says John. “His family spoiled him.”

Today, John carries his father’s marine dog tags, and he has seen all of Lana Turner’s movies. He has even visited the house on North Bedford Drive in Beverly Hills. He wants to meet Cheryl. “I would like to sit and talk to her, just to find out, really, what is in the back of her mind . . . is it true or false or whatever?”

When I finally take my leave, walking out on a quiet street under the pale winter sun, the distant mountain peaks serve as a dramatic reminder that I am half a continent away from Woodstock. John Ibrahim, still wary of a reporter, waves goodbye from the driveway.

He had told me he was an emotional man, and at one point as we talked and traded information, he wiped tears from his eyes. Not strictly out of sadness, I think. We invest such hopes in our heroes, our friends, our spouses, our fathers. We make up our stories about them, contend with the facts. In they end, they don’t so much disappoint us as leave us unknowing.

Photograph: Bettman/Corbis