UPDATE (11.14.12): Rita Crundwell pleaded guilty to fraud on November 14 in federal court in Rockford.

It was time. The three men, in standard-issue FBI suits and ties, arrived at Dixon City Hall just after nine on the morning of Tuesday, April 17. They chatted breezily with Jim Burke, the mild-mannered, silver-haired mayor, who smiled and nodded from behind a cluttered desk in his office on the second floor. But for the badges tucked into the men’s wallets and the guns holstered on their belts, the gathering might have looked like a few insurance salesmen debating weekend tee times.

As the small talk petered out, however, a chill settled over the room. Burke looked up at the men. “Are we ready?” he asked.

The lead agent, Patrick Garry, nodded. “Yes. Let’s bring her in.”

Burke reached for the phone and punched in the number for the comptroller. “Rita, would you mind stepping into my office for a minute?”

“Sure,” Rita Crundwell answered brightly.

For five long months—ever since Dixon’s city clerk, Kathe Swanson, had stumbled upon a curious bank statement from an even more curious bank account—Burke had been helping the feds unravel an embezzlement scheme so vast and so brazen it seemed almost inconceivable. Tens of millions of dollars had been siphoned from the tiny rural city’s operating budget. The money was being dumped into a mysterious account and allegedly spent on everything but city business: jewelry, fancy clothes, a custom motor coach, boats, property in Florida, luxury cars, hundreds of the finest horses this side of Amarillo. And that was only what the feds had found in their cursory first look at the city’s cooked books.

Most stunning of all was the identity of the person suspected of masterminding the scheme: Rita Crundwell, a woman whose parents were the kind of humble, hardworking community pillars upon which Dixon’s reputation was built, a woman who had been the town’s comptroller for more than three decades, as trusted and efficient as a church tithe collector.

It was Burke who had taken the dubious bank statement to the FBI office in Rockford back in October 2011. Agents instructed him to hold his tongue while they investigated. As the months passed, he woke often in the night. Was this really happening?

The mayor’s thoughts turned to Crundwell’s hobby. Everyone in town knew that Crundwell, 59, who is divorced and has no children, owned and showed horses. The local paper reported on various championships she won, honors that bestowed a measure of pride on the city.

But very few in Dixon had the faintest idea of the operation Crundwell was running or of the magnitude of the double life she was leading. By day, she was a modest municipal worker with a high-school education; by night, she was a diamond-bedazzled high roller, the doyenne of a world that was a million miles in glamour and several million dollars in wealth from the cornfields and cattle farms of Illinois.

Week after week, Burke would pass Crundwell in the upstairs offices—a warren of cubicles with pile carpeting and cheap wood paneling—and pretend that nothing was wrong, trading “good mornings” with the woman he’d been told was robbing the city blind and smiling as she did. Week after week, Swanson, the city clerk who had flagged the telltale bank statement, swallowed her disgust as she watched the coworker she had once considered a friend breezing around the building.

Now the day of reckoning was at hand.

“Hi,” Crundwell chirped, sticking her head through the door.

“Morning,” Burke said. “Would you mind coming in?”

Garry wasted no time. “I’m with the FBI,” he said, displaying his badge. “We’d like to ask you some questions.”

From his desk, Burke studied Crundwell. If she has an ounce of shame, he thought, it will show on her face. When he saw her expression, the unwavering calm smile, he was stunned. “I was looking right at her,” Burke recalls. “And the look on her face never changed. Absolutely never changed.”

The mayor would have been even more aghast had he known what the world soon would: the amount the feds allege that Crundwell stole. Since 2006, according to an indictment filed in May in U.S. District Court, Crundwell filched some $30 million, or an average of $5 million a year—more than half of Dixon’s entire operating budget over that period. From 1990 to 2006, she stole another $23 million, the feds say, bringing the grand total to an unthinkable $53 million.

If the allegations against Crundwell prove true, she not only is the biggest municipal embezzler in U.S. history but ranks fifth among embezzlers of any kind, says Christopher Marquet, CEO of Marquet International, a Boston-based security consulting firm that specializes in employee misconduct. And though the amount that Crundwell is alleged to have stolen does not reach Madoffian proportions, it’s still “an outrageously, grotesquely huge amount,” Marquet says. “That she was able to do that and no one smelled it—it almost seems not possible.”

Crundwell awaits trial on a single count of wire fraud, for which she could face up to 20 years in federal prison and a $250,000 fine. In late September, state prosecutors added another 60 counts of felony theft, each of which carries a sentence of 6 to 30 years behind bars. If she is found guilty of all counts and the judge does not allow her to serve her sentences concurrently, she could spend the rest of her life in prison.

Meanwhile, Crundwell is free on a personal recognizance bond of just $4,500. The bond is so low because a judge deemed that Crundwell does not pose a flight risk—she has been lying low at her boyfriend’s place in Beloit, Wisconsin—and, sources say, because she has been cooperating with the feds. She has not fought the seizure and sale of almost all her assets by the U.S. Marshals Service, including more than 400 horses. Some of their names are almost comical in their irony: I’m Money Too, I Found a Penny, Good I Will Be. “These horses represent some of the best raised and bred in the quarter horse industry,” Darryl McPherson, U.S. marshal for the Northern District of Illinois.

Even though Crundwell pleaded not guilty in May, she acknowledged in the initial FBI interview in Burke’s office that she used “proceeds that she wrongfully obtained” to buy and maintain horses, among other things, according to court documents. Her lawyers, Paul Gaziano and Kristin Carpenter, who declined to comment for this story, are public defenders. Observers expect her to change her plea to guilty in the coming months.

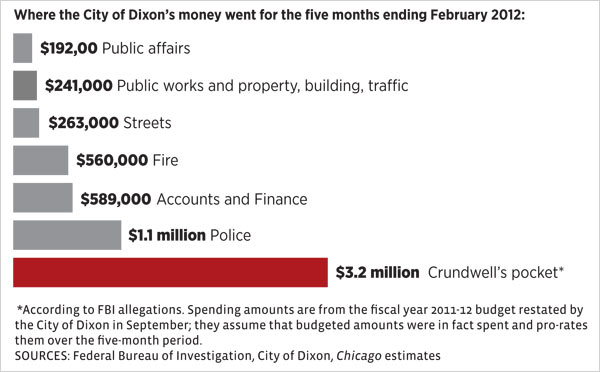

Despite the ongoing liquidation of Crundwell’s property, the City of Dixon stands to get only a fraction of its missing $53 million back. That’s galling enough to the citizens. Further fueling their outrage is that Crundwell pulled off this alleged crime during a period when the city was gasping financially. When the chief of police begged her for the money to buy a few more radar guns, a couple of new squad cars, some new uniforms, only to be told that, sorry, there just wasn’t enough money. When the budget of the city’s beloved Municipal Band had to be cut in half, forcing the townspeople to raise money to make up the difference. When officials were compelled to slash the police, cemetery, and street departments and leave vacant jobs unfilled. “The city is in a fiscal crisis,” said the finance commissioner, David Blackburn, in a City Council meeting in October 2011.

If what the feds say about Crundwell is true and she was able to face the townsfolk with a bright smile every day, “well,” Burke says, “it is sickening. It shows she didn’t give a shit about our town.”

What Crundwell is alleged to have done isn’t the only cause for outrage in Dixon. After the tornado of her arrest passed, many more funnel clouds, equally dark, have dropped: How on earth could this have happened? How could no one have noticed? How was it possible for a small town not to miss that much money?

Two hours west of Chicago, perched on the banks of the Rock River, amid the cornfields and pastures that form large green checkerboards across the state’s northwestern farm belt, Dixon could be a back lot for a Capra film on all that is best about small-town America. Limestone courthouse, old-fashioned downtown, flag-flapping front porches—they’re all here. So are two bronze statues commemorating the years that Ronald Reagan spent in town. One shows Dutch astride a horse; the other gleams near the former president’s boyhood home, at 816 South Hennepin Avenue, Dixon’s primary tourist attraction.

Something else—ominous in retrospect—summons a small-town feel: the unusual system of governance. Since 1911, Dixon has been run by the commission form of government, an old model used by only about 50 of the 1,300 municipalities in Illinois. Power is divided among five people: a mayor and four part-time commissioners who oversee their own fiefdoms (public property, public health and safety, streets and public improvements, and finance).

The positions pay a pittance—the mayor makes $9,600 a year; the commissioners, $2,700 each, according to the annual budget—which means that most officeholders juggle their duties with full-time jobs and spend limited time at City Hall. The owner of a carpet and flooring store served as finance commissioner for a number of years. He was succeeded by a business teacher and athletic coach down at the high school, Roy Bridgeman, who served for more than two decades. As for Mayor Burke: he runs his own real-estate firm.

The problem is that “the commissioners are just citizens,” says Jim Dixon, a retired attorney who served as mayor from 1983 to 1991 and is a descendant of the town’s founder. “Some of them may not always have been qualified for the areas they were elected to oversee.” Dixon says he pushed, unsuccessfully, to change to the far more common city manager model of government.

Still, the commissioner system made for a neighborly and easygoing approach and seemed to accomplish the goals that gave rise to its adoption in the first place: placing a check on the power of the mayor’s office and curbing the possibility of corruption. It didn’t hurt that it also saved the city money on the salaries that a professional city manager and staff would command.

Until that day this past April—when word spread that the FBI had taken over City Hall and that Rita Crundwell had been frogmarched down the back stairs in handcuffs—the idea that such confidence could be either deeply misplaced or dangerously naive never seemed to occur to anyone.

And even if someone did have ill intent—a silly notion, given that most of Dixon’s officials had known one another for decades—it seemed highly unlikely that they could get away with anything. Not with Rita Crundwell watching the purse strings. She knew the books too well, was too smart and scrupulous. As finance commissioner Bridgeman (who did not respond to a request for an interview) told the City Council upon his retirement in April 2011: “Rita Crundwell is a big asset to the city. She looks after every tax dollar as if it were her own.”

One of six children, Rita Crundwell (née Humphrey) grew up in the cow-patty and chores-at-dawn world of a modest farm just off U.S. 52 on the southern outskirts of Dixon. On Sundays, Caroline and Ray Humphrey and their three boys and three girls piled into a pew at Dixon’s Immanuel Lutheran Church.

The Humphreys were known as the kind of salt-of-the-earth people who formed the backbone of the town in the days before chain stores and fast-food joints became as ubiquitous as grain silos. “I can remember [Caroline] coming into town in her beat-up pickup truck,” says Joseph Rock, a local farmer. “[Her face] was weathered and her hair was pulled back. She’d be wearing boots. She looked like she was a hard worker.”

But the family wasn’t all work. Caroline, in particular, had a cherished avocation: showing quarter horses.

The nation’s most popular breed, the American quarter horse has long held the imagination of equine lovers. It is known for its looks (muscular, though more compact than a thoroughbred) and athleticism (its name comes from its speed in races of under a quarter mile).

Agile and good at working ranches, this is the horse that helped win the Wild West. A quarter horse can cost anywhere from a few thousand dollars to $250,000 or so. Preparing to show one can be costly too. Like dog shows, horse shows involve training, grooming, and parading prime specimens before judges.

The family hobby was more than just pricey; it was a source of conflict between Rita and her younger sister, Linda. The two never really got along, says a childhood friend who went to school with both girls and remains friends with Linda, who today owns a Dixon saloon called Tipsy. (She asked that her name not be used.) Some of the fights may have stemmed from resentment over who got the best horses to show. “Whatever Rita wanted, Rita got,” says a family member who asked not to be identified. Other members of Crundwell’s family didn’t return phone calls seeking comment.

A pretty girl with long brown hair and big round glasses, Rita Humphrey was smart—of the more than 300 Dixon High School students named to the National Honor Society, she landed in the top 20—and a hard worker like her mother. Through the school’s work-study program, she got a part-time job at City Hall, where she impressed her bosses. “She just caught on to everything so well,” recalls Walter Lohse, a city commissioner from 1967 to 1987.

Rita had planned to attend nearby Sauk Valley Community College after graduation, but when Darlene Herzog, Dixon’s first comptroller, encouraged her to stay on at City Hall, she decided to skip it. “Darlene took Rita under her wing,” says Lohse. “We hired Rita full-time because Darlene spoke so well of her.”

It didn’t hurt that the teenager was already familiar to the denizens of City Hall, both past and future. Burke, for example, had known her for years. “My real-estate office sponsored a girls’ baseball team she was playing on,” he recalls. “We had a pool then, and I remember she and all these girls came up to our house once. So I’ve known her for a long time.” Bridgeman—who was her supervisor during most of the time she was allegedly stealing—taught Rita typing at Dixon High. (“He was a great teacher,” Crundwell told the local newspaper when Bridgeman retired. “I loved him.”)

Three years out of high school, in 1974, Rita met Jerry Crundwell. An engineer with Homer Chastain and Associates, an engineering firm based in Decatur, he was working on a highway project with Rita’s brothers. Though little is known about their courtship (Chicago was unable to track Jerry down; through relatives, he has refused to publicly discuss her), something clicked. They were married that same year.

As the years went by, Rita stayed at City Hall, working her way up from secretary to treasurer. Finally, in 1983, health problems forced Herzog to retire as comptroller. Her replacement was obvious. “Rita was very efficient, very pleasant. She got along with everyone, and she knew the job in and out,” says Jim Dixon, who by then had begun his first of two terms as mayor. “She seemed like a perfect fit.”

Rita’s personal life wasn’t so perfect, however. In 1984, her mother died; two years later, she filed for divorce, alleging “extreme and repeated mental cruelty.” Jerry did not show up at the hearing.

The divorce was granted, and their few assets were split. Rita was awarded their $80,000 house at 1673 U.S. Route 52 and her six-year-old Oldsmobile Cutlass. Jerry got to keep his 1983 truck.

By all accounts, Rita Crundwell blossomed both professionally and personally after the divorce. Because Dixon’s comptroller was not elected but appointed, her job was secure. She began to make herself indispensable, tightening her grip on the city’s books and studying the finer points of the complex and politically charged budget process.

By the late 1980s, says Jim Dixon, she controlled virtually everything having to do with the city’s money. She balanced the checkbook. She wrote the checks. She made the deposits. She requested funds. If people wanted money for a project, it was Crundwell to whom they appealed. Financial statements were sent to a City of Dixon post office box that she controlled; when she was away, a relative collected the mail.

That mail would have included statements for the secret account authorities say she created in 1990.

Though it was not a city account, Crundwell tried hard to make it look that way, federal sources say. She designated the City of Dixon as the primary account holder, with a second account holder listed as “RSCDA c/o Rita Crundwell.” Not that she needed to: Apparently no one at City Hall—or at the bank—ever questioned her about it.

As commissioners came and went, it was Crundwell—who had spent her entire adult life working for the city—who showed newcomers the ropes (Burke says five city councils, three mayors, and three financial commissioners came and went during Crundwell’s alleged spree). She knew what bills needed to be paid and when, whose arm to twist when checks were late. And she was meticulously organized. “I could go into her office and say, ‘Rita, do you have a copy of the cable TV contract from 1986?’” Burke recalls. “And she’d go right to a drawer and pull it out.”

Cheerful, smart, and attractive, she represented Dixon well, professionally and socially. During the 1980s, for instance, she played on the softball team of the accounting firm Clifton Gunderson, which would eventually prepare audits for the city.

If there was one complaint about Crundwell’s work—and it wasn’t so much a complaint as an understanding—it was the amount of time she took off for quarter horse competitions. She had been participating in them at the regional level since 1978. “We’d occasionally see something pop up in the paper about some ribbon or other that she’d won,” recalls Lohse. In 1985, the year before her divorce, she won both the Indiana State Quarter Horse Championship and a national quarter horse title in Texas.

By the mid-1990s, however—unbeknown to the folks down at City Hall—Crundwell had become far more than a hobbyist. She was now a major player in the big-money, high-stakes horse world. And her success demanded requests for more and more time away from the office.

In 2011, for example, in addition to her four weeks of paid vacation time, Crundwell took off an extra 12 weeks. But even there, she seemed scrupulously honest. “What she did was, she would dock herself for her time off,” recalls Burke. So instead of the $83,000 annual salary that Crundwell was scheduled to be paid—not bad for a small-town resident without a day of college—she would wind up making about $61,000.

“The ladies up here [in City Hall] told me that if we wanted to get in touch with her, she was always accessible. They said she had computers in her motor home and would call right away,” Burke explains. “I think most of us thought, Well, she’s doing the job, and when she’s gone, she’s docking herself for it. We’re actually kind of making out on the deal.”

Starting around 1990—the year the feds say she opened the secret account—Crundwell began investing heavily in horses. Her collection went from a handful of mares and stallions to a trophy-winning herd of several hundred championship-caliber animals.

By the end of the decade, she had developed a multimillion-dollar breeding and showing empire so vast that even the high rollers of the horse world were taken aback. “People said, ‘Where did this woman come from?’” says Sally Hope, a certified appraiser with the American Society of Equine Appraisers, who watched Crundwell’s rise. “I was showing with my daughter in the ’80s, and I [had] never heard of Rita Crundwell. She came in with everything blazing.”

In 1997, Crundwell had stables built for her horses on the 6.9-acre property in Dixon that her mother left her, according to records. (She later renovated the house, doubling its square footage, and had an in-ground pool installed.) In 2006, she turned a nearby 88-acre parcel she had bought for $540,000 from her brother Richard into Rita’s Ranch: a breeding and showing operation that included a 20,000-square-foot barn, complete with an arena, an office, and stalls.

While Crundwell kept most of her horses at Rita’s Ranch, she began stabling some at the Meri-J Ranch in Beloit, Wisconsin, little more than an hour north of Dixon. It was run by her new boyfriend, Jim McKillips, a longtime fixture on the competitive quarter horse circuit. (The McKillips family had originally owned the ranch but later sold it; Jim, now 67, stayed on as a paid manager and lives in a house on the property. He did not respond to a request by Chicago for an interview.)

By the late 2000s, Crundwell had established herself as the undisputed grande dame of the competitive quarter horse circuit. Its two showcase annual events—the All American Quarter Horse Congress in Columbus, Ohio, and the American Quarter Horse Association World Championship Show in Oklahoma City—are among the biggest conventions in the world. The Columbus show, for example, draws hundreds of thousands of people each year, placing it just below the Democratic and Republican National Conventions in size. The events attract socialites, captains of industry, and celebrities such as Robert Redford, Harrison Ford, and Lyle Lovett.

Crundwell would sweep into town in a vehicle so grand that the term “mobile home” doesn’t do it justice: a 45-foot Liberty Coach with marble countertops, tile floors, leather-wrapped railings, a king-size bed, five satellite televisions, even a washer and dryer. Accompanying the coach were custom-painted 10-horse trailers, some with attached living quarters, all emblazoned with her initials. (The typical competitor brought a horse or two.) One trailer, a Featherlite, cost nearly $260,000. “Everyone knew that Rita Crundwell was coming with the best horses in the country,” says Hope.

A retinue of hired hands would appear to clean the stalls, brush and exercise the horses, and set up stall decorations. “There would often be a luxury car of some kind,” Hope adds. Plus a couple of gleaming new Ford F-650 pickups. All around her encampment, Crundwell would string yellow police tape.

The setup in the parking lot across from the exhibition hall was only the beginning. Inside the arena, where breeders and performers put up booths to advertise wares such as saddles, costumes, and tack, Crundwell erected a replica of a log cabin as an entrance to her personal exhibit. Custom stall curtains hung next to expensive decorations. “She would have shelving where she would place the trophies that she had won, and she won a tremendous number of trophies,” recalls Debby Brehm, a horse owner from Lincoln, Nebraska, who has competed against Crundwell many times. Out front, a bartender would serve cocktails from a fully stocked bar.

While City Council members back home in Dixon were lamenting tight budgets, cutbacks, and a cash-flow crisis bordering on calamity, Crundwell was hosting lavish parties and dinners with her boyfriend at her side. Crundwell’s 57th birthday bash, thrown by McKillips in Venice Beach, Florida, featured “delectable” jumbo shrimp cocktail, Caesar salad, prime rib, and “other mouthwatering entrees,” wrote fellow competitor Dakota Diamond Griffith in an article for the website Go Horse Show. In 2009, the site named McKillips the best horse show tailgater, noting: “There’s never a shortage of food when Jim’s behind the grill.”

Crundwell became known for her fashion sense. She arrived at that birthday party in a snow-white coat with a plush fur collar. (“Where does she find these items!” gushed Griffith.) The shirts she wore to the shows were usually beaded and sequined, Hope recalls. “They’re beautiful. I went to look at a couple of the blouses she wore. The used ones were $1,800 a pop—and Rita didn’t wear used. I thought, Gadzooks!”

And Crundwell won. Big. At the time of her arrest, her horses had taken 54 prizes at the Oklahoma City world championships, the Oscars of the quarter horse world, which in 2011 drew competitors from eight countries. The American Quarter Horse Association had named her the leading owner—an honor that goes to the person who racks up the most points for horses he or she enters—for the eighth straight year.

Brehm and Hope didn’t give much thought to where Crundwell’s money was coming from. “I knew she worked for the city in Dixon, so I kind of wondered,” says Brehm. “But the story I heard was there was something from her past, where she had inherited land in the Chicago area, so I never thought anything of it.”

Neither, apparently, did Dixonites. That’s partly because, for all her flash on the horse circuit, Crundwell appeared modestly in town, never in expensive cars or dripping with jewels. “She wasn’t showing any diamond rings or anything,” Burke says. “It wasn’t like she was driving that [$2 million] bus around.”

It’s also partly the classic Midwestern reluctance to pry. When asked if anyone wondered where Crundwell got the money to fund her horse empire on an $83,000 salary, Burke says no: “We all knew that she had these horses, but, you know, there were big write-ups about her in the papers that she’s winning all these national championships, and there were stories flying around town that she was selling horses for $250,000, $300,000. So we thought that this was what was providing her this nice income: a successful horse business.”

It was true that Crundwell sold horses. It was also true that she collected stud fees and sold semen from her championship stallions and that she won hundreds of thousands in prize money. But those revenues were a drop in the bucket of the cost to maintain her horses—not to mention her own travel expenses and lavish spending on jewelry, clothes, cars, and parties. That lifestyle requires the kind of deep pockets that even millionaires struggle to fill. When she was arrested, a former ranch hand told me at Rita’s Ranch one day in late September, “it finally made sense. I know how much this stuff costs, and we were always wondering where she got the money.”

Simple is elegant. And the strategy used by Crundwell, the feds say, was in some ways very simple, at least for a person who knows her way around bank statements and balance sheets. Crundwell essentially shell-gamed a variety of city tax funds, then doctored the books to make balance statements look as if they matched, authorities allege.

The scheme, the feds say, started with the Illinois Fund, a money market mutual fund open to Illinois municipalities. Towns deposit their revenues from taxes, fees, federal grants, and the like into the account, hoping to maximize the interest they earn while the money is waiting to be spent.

The City of Dixon—in the person of Crundwell—could make withdrawals from the Illinois Fund. According to authorities, Crundwell wired money from there into various city accounts, such as the “corporate,” “motor fuel,” and “capital development” funds, and a city money market account. She fattened the capital development fund by transferring money from the other accounts into it.

From that capital development fund, she would write checks made out to “Treasurer.” “Anybody looking at it would conclude that it must be a payment to the Illinois state treasurer and she was the treasurer on the other end of the check,” explains Carol Jessup, an accounting professor at the University of Illinois Springfield and a former internal auditor for the Illinois Capital Development Board who has studied Dixon’s finances. Instead, Crundwell deposited the money into the secret RSCDA account, the feds say.

If what the feds allege is true, Crundwell succeeded for so long by cleverly exploiting the weaknesses in the system. For starters, accounting regulations were far more lax in 1983, when Crundwell took over as comptroller. “No one paid much attention to government reporting [back then],” says Jessup. “Government accounting was much more about budgets and the management of cash.”

Today, it would be nearly impossible for someone—even a government official—to open a bank account in a city’s name without city authorization, the way Crundwell allegedly did at First Bank South in 1990, adds forensic accountant Dennis Czurylo, a former special agent in the Internal Revenue Service’s criminal investigation division. Once that account was established, it got lost in the shuffle of takeovers: First Bank South gave way to Grand National Bank, which was bought by Old Kent Bank, which was in turn gobbled up by Fifth Third. New employees trying to get up to speed on old accounts would have little reason to question what appeared to be just another city account. (A spokesman for Fifth Third Bank declined an interview request from Chicago.)

What’s more, Crundwell knew that the State of Illinois was often late—sometimes by as much as a year—in making certain payments to its municipalities. So Crundwell would tell the mayor and the City Council that the state was late in sending payments “when in fact,” the federal indictment alleges, “she had fraudulently transferred those funds to the RSCDA account for her own use.”

The financial documents that Crundwell prepared for Dixon were unorthodox, to say the least. With Chicago, Jessup went line by line through the budget and financial statements that Crundwell prepared for Dixon’s last fiscal year, which ended on April 30, 2012. Jessup calls the budget an “obtuse mix of loan balances and interfund transfers with revenues, all labeled as revenue. Tracing the inflows and outflows . . . is impossible.”

Even an Accounting 101 student knows you can’t mix assets and revenues. That mixing took place on the budget, a document that auditors don’t routinely see. The people who do see it are Dixon’s mayor and commissioners—who, as you’ll recall, work part-time and are paid just a few thousand dollars each. “If the finance commissioner [Crundwell’s boss] is paid $2,700, how motivated do you think he’s going to be to do this job?” Jessup asks.

Because Crundwell was the only one who could make heads or tails of the books, it was far easier to just let her handle everything. Dixon’s leadership essentially allowed a closed-loop system in which one person controlled all aspects of depositing and spending money, plus keeping the books. “You always want to split those duties up,” says Czurylo. “In a normal organization, you would never see that kind of concentration of duties.”

The one who has come in for the most heat in the still-simmering mess is Burke. In the days following Crundwell’s arrest, an angry group took to the sidewalk in front of City Hall to demand answers; letters to the editor of the Sauk Valley Telegraph and comments in the blogosphere savaged him. “The only time it really got to me was when some people I knew well confronted me at the County Market grocery store,” the mayor says. “And this lady, boy, was she giving me a grilling.”

Jessup has some sympathy for Burke. “There’s so much more to being a mayor than the budget and finances. He has so many headaches. I’m sure that in his heart he thought the money was in trustworthy hands,” she says. “He’s responsible for being naive.”

What about the auditors, who are supposed to detect fraud? Audits, cautions Jessup, are not guarantees. For starters, responsibility for the financial statements on which the audit is based falls on whoever provides those statements—in this case, the City of Dixon. The auditor gathers and views evidence that backs up the numbers, based on standard sampling methods. The samples chosen might not show fraud. In fact, says Burke, 21 audits over the years failed to turn over any red flags.

There’s yet another complication: Dixon had two sets of auditors. Clifton Gunderson (now CliftonLarsonAllen), the firm on whose team Crundwell had played softball, compiled the data; since 2006, a solo auditor, Samuel Card, analyzed it to comply with federal regulations triggered when Dixon received an influx of federal cash. It’s possible that the mayor and commissioners did not fully understand the scope of the work being done by each auditor. Neither Card nor representatives from CliftonLarsonAllen would comment for this story, citing a pending lawsuit filed against them by the City of Dixon for failing to “apprehend and/or disclose numerous accounting irregularities,” among other allegations.

To prevent a repeat of the current catastrophe, things in City Hall will “change dramatically,” promises Stan Helgerson, one of two interim commissioners who reviewed Dixon’s books after Crundwell’s arrest. The city has eliminated the position of comptroller, hiring instead a $95,000-a-year finance director named Paula Meyer, who started in mid-September. Formerly the dean of business services at Sauk Valley Community College—the very school Crundwell hoped to attend more than 40 years ago—Meyer is charged with financial planning and budgeting. She will have numerous sets of eyes on the books, including those of every City Council member. Dixon’s commission form of governance, however, remains.

But the most fundamental question, if what the feds say is true, is not how Crundwell pulled off this brazen bamboozle but why. Why would someone with deep roots in her town, without so much as a parking ticket to her name, damage the very people who had provided her with so many opportunities? Especially when it was likely that she would eventually be caught?

Research shows that a desire for the trappings of luxury is a major motivation for male embezzlers. Female embezzlers are more often driven by the desire to take care of their families. Linda Grounds, a clinical and forensic psychologist in Portland, Oregon, who has evaluated more than two dozen women charged with stealing from their employers, has identified two other patterns common among female embezzlers. One is addiction—to alcohol or gambling, for example. Another is to “meet their emotional needs by spending money on themselves and others.”

Women in the latter category are often extremely intelligent and, on the surface, “likable, courteous, gracious, personable, well-spoken,” says Grounds. Underneath, however, they have “this quality of immaturity. . . . They don’t have a strong sense of self-esteem, and they’re kind of needy of approbation, of approval.” Compounding this is denial that their crimes will be discovered: “They don’t think forward to what the consequences are going to be when they are caught.”

Brehm, the Nebraska woman who competed against Crundwell, sensed in Crundwell a desperate need for approval. “I feel sorry for her, that she felt that she needed to take this kind of money and present this number of horses to feel like she was accepted in the horse world,” Brehm says. “It’s almost like she felt she had to set the bar higher for herself, and that once she did, she had to maintain that image.”

Cindy Hale, a journalist who has written four books on equestrians and judged numerous quarter horse competitions, says, “For someone who for whatever reason has poor self-esteem or an addiction to recognition, it’s hard to walk away. You’re at this event and there’s an entire sea of people and you’re throwing parties and rubbing elbows with celebrities and politicians and highflying CEOs and oil people. And I can see how someone’s whole identity becomes wrapped up in being that person.”

Martha Stout, a clinical psychologist in Boston who taught at Harvard Medical School and wrote The Sociopath Next Door, offers another perspective. While she stresses that she cannot diagnose Crundwell or anyone who isn’t a patient, she notes that many embezzlers are sociopaths. “The central trait of sociopathy is a complete lack of conscience,” she says. “If you don’t have a conscience—if you can’t truly love—then the only thing that’s left for you is the game. It’s all about controlling things, manipulating people, lying. The sociopath is ice-cold inside, and though he or she may spend a great deal of energy attempting to look like us—to appear ‘normal’—sometimes this coldness is the giveaway.”

One thing about Crundwell always nagged at Burke: She had a quality that was “like an invisible screen.” She was friendly, yes. Cheerful, always. But there was a part of her that couldn’t be reached. “I’ve known her for years and years, and even when she was working for the city in her teens, it was there,” the mayor says. “It was hard to define. . . . I couldn’t put my finger on what it was.”

On a crisp fall day, under a painfully bright blue sky, Rita’s Ranch, desolate for these many months, once again teems with life. There are ranchers in jeans and boots and cowboy hats; auctioneers in blue blazers and red ties, their voices barbed and twangy; families with kids, gawking under their sunglasses. And, with their coats gleaming against the high sun, their noble heads and curious eyes lifted to the crowd of some 2,000 people, the creatures who lured them here. Horses.

Conspicuously absent from this carnival-like scene, redolent with the smell of hay and dung and funnel cakes sold from stands that sprang up overnight, is the person whose initials brand the buildings yet: Rita Crundwell. The live auction to sell off 319 of her prized horses, her lavish saddles and bridles, and her 10-horse trailers that included suites with standup showers, flat-screen TVs, and microwave ovens, is underway.

Some people are clearly here to buy: The first horse auctioned—Good I Will Be, a multiple world champion—goes for three quarters of a million dollars. Another 146 horses, along with related items, brings in an additional $2.4 million. (The total haul for the two-day September auction was nearly $5 million.)

Some attendees are here for other reasons. Says Jeff Kuhn, the current streets and public improvements commissioner for Dixon: “I came to see where Dixon’s money went.”

Kuhn’s wife, Jeanne, taking in one of Crundwell’s custom trailers parked on the grounds, shakes her head. “The emotions are so varied,” she said. “From disgust, to amazement, to—look at all this beautiful stuff. And it is beautiful.”

She pauses, shakes her head. “To think,” she says, not finishing her sentence.

She moves on, with her husband close behind, her boots crunching the gravel.