Sloane Williams’s lesson doesn’t start for another hour, but she’s already warming up on a court at XS Tennis in Kenwood. Though only 15, she generates impressive power from her long, thin frame, slamming serve after serve into an invisible opponent’s court. Her early arrival piques the interest of her instructor, XS Tennis founder Kamau Murray, for a variety of reasons.

“Look at her,” Murray says. “Most kids just sit around until it’s lesson time. She’s out there working. That will pay off for her.”

But since it’s barely past two o’clock on a Wednesday, her presence also raises a question. “Why aren’t you in school?” Murray asks her pointedly.

“I was sick today, so I thought I’d come here,” answers Williams, a sophomore at Kenwood Academy.

“You were sick from school, but you’re well enough for tennis?”

“I’m feeling better now.”

Murray isn’t buying it. “I love the effort, but academics come first,” he reminds her.

Advertisement

The real teaching moment, though, happens later, in the waning minutes of their lesson. As Murray fires ball after ball at her, Williams grows fatigued. She stops moving her feet into position, instead relying on her long reach. Most of her shots go wild.

“Are you thinking about winning the next point, or are you thinking about being tired?” asks Murray, who is quickly losing patience.

“What?” Williams replies, breathing heavily, slumping onto her racket, physically begging for mercy.

“I said, ‘Are you thinking about winning the next point, or are you thinking about being tired?’ ”

“Being tired,” she answers in a huff.

“Come on!” Murray commands. “Think about the next point and win it!”

He smacks a forehand to her right, and Williams steps into position perfectly to fire a return down the baseline.

“Thank you!” Murray says in triumph. “You can never win a point if you’re thinking about being tired. Do not forget that. It’s always, always, always about the next point.”

Williams drops onto a bench and inhales a red Gatorade. It’s hard to tell whether the lesson has been absorbed. Still irritated, Murray walks off the court. “Sissy girl,” he mutters to himself.

“Sissy” is a word that Kamau Murray uses with rather jarring frequency. But he is not a man who worries about political correctness or hurt feelings. He is about getting results, particularly when it comes to his most promising players. “You can be a wonderful person and do wonderful things,” he says, “but our country is structured so that if you don’t win, no one cares.”

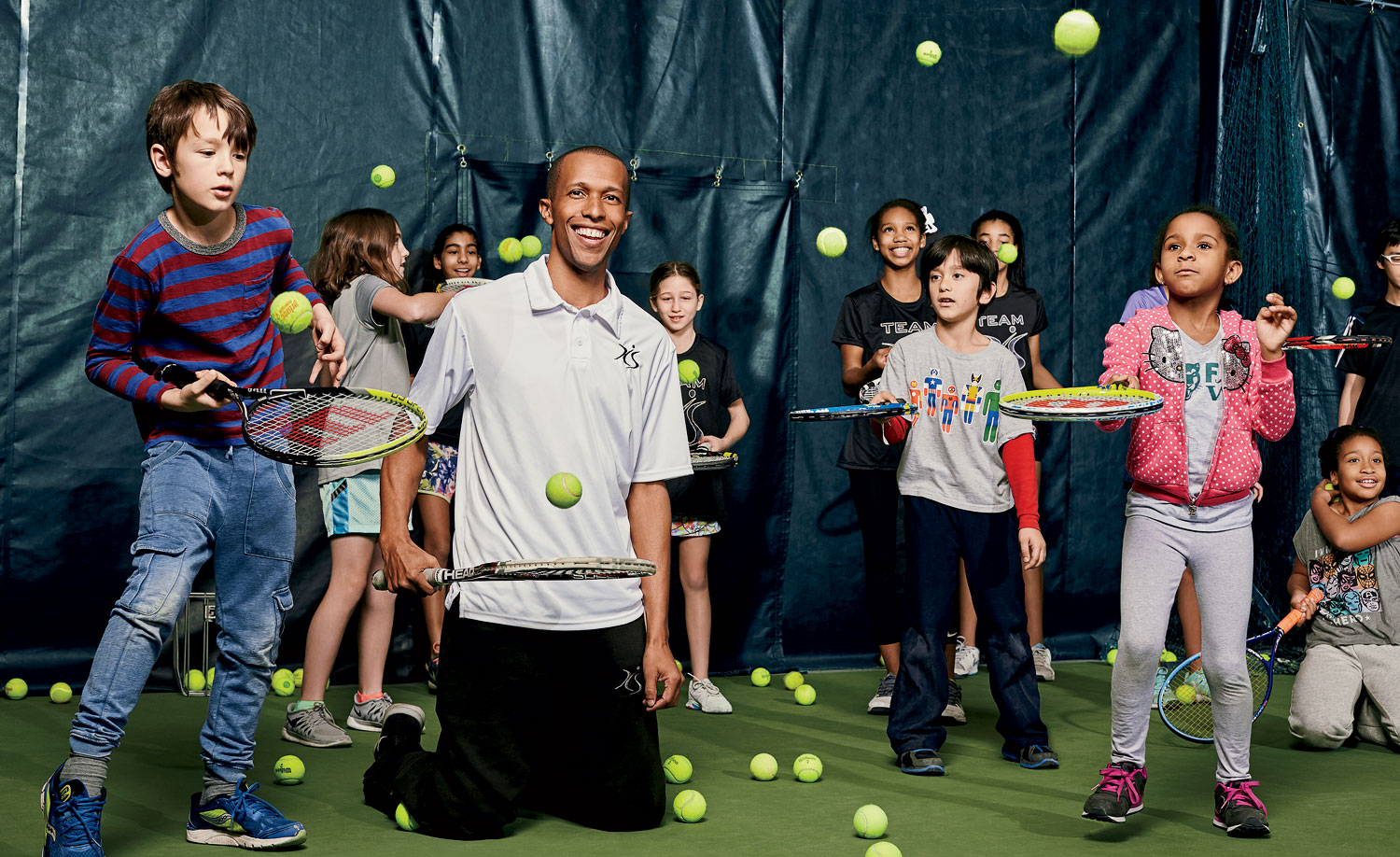

Whatever you think of Murray’s approach, the former college player and ex–pharmaceutical rep has almost overnight become the best-known, best-connected tennis coach in the Chicago area, and his reputation is growing outside the city as well. Recently, the 35-year-old was hired to assist Sloane Stephens, a pro ranked in the top 50. When not joining the Florida native at tournaments around the globe, Murray plies his trade on the South Side, not exactly known as a tennis hotbed.

If he has his way—and he’s relentless about getting his way—that will soon change. Last summer, Murray’s nonprofit, XS Tennis and Education Foundation, which operates the Kenwood club, broke ground on a $12 million new base at 54th and State in Washington Park, on land where the notorious Robert Taylor Homes once stood. The massive new center—backed, both financially and otherwise, by the city, Mayor Emanuel personally, tennis great Billie Jean King, and other notables—will be something of a cathedral to youth tennis, rising in a distressed part of Chicago. Spread across more than 13 acres and anchored by a 116,000-square-foot building, the XS Tennis Village, as it’s being called, is scheduled to open late this year and will feature a whopping 27 courts—12 indoor and 15 outdoor (four of them clay).

Murray’s plans for the center are wildly ambitious. For one thing, he wants to attract major national junior tournaments to the South Side. But most important, he sees it as a way to ramp up his foundation’s mission: to improve the lives of as many neighborhood children as he can.

His pitch to parents is simple: More than a thousand college tennis scholarships go unused each year, particularly on women’s teams, because of the lack of qualified talent. “I tell them that if they follow my plan,” he says, “I can guarantee their kid a free college education. So many kids, they drop out mentally, out of school and out of life in general, because they feel like there’s no light at the end of the tunnel. If I can say, ‘If you do right, I will give you this opportunity,’ there is a light: you will go to college.”

He’s made good on that promise for nearly three dozen of his students who’ve landed tennis scholarships over the past eight years. The rub, of course, is that his guarantee hinges on students following his plan. And that plan means putting in the kind of work, both on the court and in the classroom, that he mercilessly demands.

Advertisement

“His style probably doesn’t work for everyone,” says Natalie Whalen, a 19-year-old graduate of magnet high school Whitney Young who began lessons with Murray when she was 12 and now plays at Indiana University. “But I like him because he’s real. He always found the right thing to say to improve my game. Actually, I think my best learning days came when he was extra critical.”

Murray makes no apologies for his brash approach, saying that scholarship-caliber athletes need to be pushed to reach their full potential. From day one, he tells parents and kids that they’re all in it for the long haul—until high school ends. It’s an unwritten contract: He’s completely invested if they are. “There has to be a level of trust and commitment with all parties involved,” Murray says. “When I see a young kid for the first time, I can visualize how this kid needs to play to be successful. I can visualize the coaching process from beginning to end. You have to see that process through. Every kid is different, and you have to recognize early how to coach each one individually, to maximize that player’s individual abilities.” His standard rate is $80 an hour for individual lessons, but the foundation offers reductions, from 25% to 100%, based on family income; academic tutoring is free.

It’s hard to argue with his results. Over the past few years, he has produced a stellar roster of players (see “Kamau Murray’s Star Students,” below), most notably Taylor Townsend, the 19-year-old pro he coached in her first years on the circuit. The Englewood native, who reached No. 1 in the junior rankings in 2012, was heralded at one point as “the next Serena.” Though Murray and Townsend parted ways in the spring of 2015 (“Sometimes players need to hear a new voice,” says Murray), his involvement with her boosted his reputation and his Rolodex.

For players who remain committed to Murray’s program, XS Tennis represents not just a pathway out of their circumstances but an everyday sanctuary from urban ills. “As a single mom, I can say the reason my son didn’t wind up on the street is tennis saved him,” says Renell Perry, a retired IBM executive from Jackson Park Highlands. Her son, Adam Wright, a product of XS Tennis, went on to play at Tennessee State University. “My son was always in this tournament or that tournament, so there wasn’t that idle time that can get young men in trouble. When I dropped him off to play tennis, and those doors closed behind him, I knew he was safe. I am one of the mothers down here who thanks God for Kamau.”

In his spare, glass-windowed office, Kamau (pronounced Ka-MOW) Murray thumbs through his text messages and points to one big name after another. “Look at this from Billie Jean King,” he says, holding out his iPhone. The message reads: “Keep on changing the world, Kamau, XOXO.” Murray brushes a hand across his tightly cropped hair and leans back in his chair, his youthful face breaking into a wide grin.

He clearly relishes mixing it up in the rarefied world to which tennis has provided access. The Pritzker Traubert Family Foundation, the Lacoste clothing company, Mesirow Financial, Northern Trust, and Guggenheim Partners—these are only a handful of the heavy hitters who have contributed financially to Murray’s vision. “I had never met anyone with a net worth of $2 million until a few years ago,” he says. “Now I text a few of them on a regular basis.”

Murray paid himself just $8,820 out of XS Tennis in 2013, according to tax records, though he has since quit his pharmaceutical rep job and this year will start taking a full-time salary from the foundation. His wife, Jennifer Anderson-Murray, is a high school guidance counselor with Chicago Public Schools. “We are never going to be rich,” he says. “I guess we are both bleeding hearts.”

Murray’s own story begins not far from where his tennis center is going up. He was raised in South Shore, a working- and middle-class neighborhood along the lake, in a family of talented athletes. His father, Leonard Murray, a Cook County judge, played baseball at St. Francis University in Pennsylvania, and each of Murray’s three siblings earned sports scholarships. One sister played volleyball at Illinois State; another ran track at Howard. Murray’s older brother, Malik, played basketball at DePaul and is now a vice president at Chicago-based mutual fund giant Ariel Investments. “I’m the sissy in the family because I play tennis,” says Murray, who is 6-foot-1 and a rail-thin 165 pounds. “But I didn’t choose tennis. Tennis chose me.”

His favorite sport growing up was basketball. But when he got to high school, at Whitney Young, and realized he would be a bench player at best, he turned to tennis. (That basketball team included his best friend and XS Tennis benefactor, Quentin Richardson, who went on to play for DePaul and the NBA’s Miami Heat.) The shift paid off. Murray became one of the state’s best players and also got his first chance to coach. At the start of his senior year, the coach quit, and Murray, as team captain, more or less filled in. His play earned him a scholarship at Florida A&M. When he graduated, the university hired him as a coaching assistant and funded his master’s degree in finance.

After grad school, Murray participated in a few professional satellite tournaments, but it was clear to him that playing tennis wasn’t going to pan out as a career. He landed a job in marketing for pharmaceutical giant Pfizer and spent a couple of years in Manhattan before transferring to a sales role back in his hometown in 2005. To earn some extra money and stay involved in the sport he had grown to love, he devoted a few evenings a week to teaching tennis to a handful of South Side children. Soon more parents came calling, and then more.

Eventually, by 2008, he realized he needed to expand his capacity. For $90,000, he estimated, he could buy out the contract of the tennis operator at a Bally fitness center at 47th and Lake Park—the same facility where he’d learned the game as a boy and where he was now coaching part-time. Problem was, he didn’t have $90,000.

He turned to his father. “You are out of your mind,” Leonard Murray told his son. “You went to school, got a degree, and you want to do all this tennis stuff?”

Advertisement

So he played on his dad’s emotions. Less privileged kids on the South Side deserved the same opportunity to go to college as suburban youngsters, he told his father, who caved. The pitch wasn’t just a line. “I couldn’t be a jerk and just walk away and let this thing die,” he says.

Malik Murray isn’t surprised his brother has taken an altruistic path. “My mom [Linda, a retired CPS assistant principal] was the dreamer in the family, and she always pushed people to rise above themselves, challenge themselves, to believe that everything is possible,” he says. “That philosophy rubbed off on my brother.”

Murray set up XS Tennis as a foundation and began seeking out students with potential. He poked around CPS after-school tennis programs, guest-taught PE classes, asked gym teachers for recommendations. What he was searching for, more than anything, were pure athletes. “That girl who takes tennis lessons and plays the flute, that girl probably isn’t going to get anywhere, no matter what I do,” Murray says. “I am looking for the athlete who can catch a tennis ball in one hand on the run, who plays soccer or basketball or runs track, who’s laser-focused on the ball. Look at Serena Williams. She isn’t necessarily the best female tennis player in the country, the best ball striker. But she is the best female athlete in the country, and she happens to play tennis.”

Several students in his first crop began running over more highly touted suburban opponents, rising in state rankings. “Suddenly these black girls from the city are winning tournaments, and players are asking my kids, ‘Hey, who’s your coach? Would he work with me?’ ”

One of the players who knocked on his door was Steven Hill. Despite being only 5-foot-5, Hill, like Murray, initially yearned to be a basketball player—until, that is, he missed the tryouts at Lincoln-Way North in south suburban Frankfort. So five years ago, when “Lil Steve,” as Murray calls him, was 14, his mother enrolled him in XS Tennis. Hill put in the work Murray demanded but faced other obstacles. He didn’t compete in many regional and national tournaments because his parents couldn’t afford to send him. That meant he couldn’t achieve a ranking that would catch the eye of college recruiters. When Murray reached out to schools on Hill’s behalf, he got a cold reception. But he kept calling, finally persuading a coach at Morehouse College in Atlanta to let Hill try out. The school offered him a partial tennis scholarship—enough that he could afford to go.

“I wouldn’t be here today without Coach Kamau,” says Hill, now a freshman studying business marketing. “When it comes to tennis, I owe him everything.”

For as long as Malik Murray can remember, his younger brother has spoken his mind. As a boy, Kamau would voraciously read newspapers and magazines, then rant about opinion pieces he felt were off the mark. And when Malik played basketball for DePaul, Kamau, then about 14, would approach Malik’s teammates after games to point out what they had done wrong. “To come into a locker room and call out a guy who’s six inches taller—well, my brother has never been short on bravado,” Malik says.

Mayor Emanuel got a whiff of that when Murray came calling in 2014, looking for funding for his planned tennis mecca. Murray says he provided City Hall with evidence of the good his program was doing—how many students he’d helped land scholarships, how his program, in conjunction with the University of Chicago, provides free after-school tutoring. He also talked about the tourist component—how thousands of young players and their families would visit Chicago for tournaments if the facility were built. And he promised it would include a fitness center and multipurpose space for dance and other activities—all just a few blocks from the likely site for the Obama presidential library, further spurring development in the area.

The way Murray tells it, the mayor was impressed but still not convinced that the city should chip in financially. So Murray played his trump card: Billie Jean King, already a backer of his foundation. “I told Billie, ‘I need you to come here,’ ” Murray says. “Then I called the mayor and I said, ‘I got someone who wants to see you and talk about my project.’ We walked in and the mayor said, ‘Oh, wow, OK.’ Now his ears have perked up and this is something more than just an idea. I think people don’t always get my reach, at least not at first. I have to show them how far my arms reach.”

The tactic worked: The city is providing $2.9 million in tax increment financing for construction. Emanuel even dropped $5,000 of his own money and strong-armed a luncheon of fence-sitting investors for another $200,000. “Kamau has the data to back up the success of his program, but it’s even harder to say no to his sincerity and earnestness,” Emanuel says. “This is a guy who could be making a healthy six figures doing something else, and yet he’s selflessly working on behalf of these kids. Who couldn’t get behind that?”

Advertisement

Murray claims to be inherently shy (“I’m pretty good at one-on-one interactions, but at public events I wind up standing against a wall”). As a former salesman, though, he knows the importance of making a strong, lasting impression. And that has served his mission well, says Derek Douglas, vice president of civic engagement for the University of Chicago. (Tutoring is not the school’s only connection with XS Tennis: U. of C.’s tennis team practices at the club.) “Kamau has an incredible voice and a gift for making you believe in something,” Douglas says. “We’re lucky to have a leader like him on the South Side.”

Douglas was so impressed with Murray that he encouraged him to speak at a January 2015 community forum about locating the Obama library in Washington Park. That effort was running into opposition from parkland preservationists, public housing advocates, and other activists. If Murray was to build his tennis center nearby, he’d need these people on his side. “I don’t think many of them expected me to be black,” Murray recalls of the audience at Washington Park’s field house. “All they heard was ‘City proposes a tennis village.’ And they are thinking, OK, what Jewish developer has Rahm found now? So I walked into the town hall meeting, and the stunned faces were like, Oh, you’re a Negro! And I was like, Yes, I am a Negro.”

Dressed in black Nike tennis attire, Murray stepped to the microphone and took direct aim at those seeking to preserve the park for green space. His program had provided free lessons for low-income children on Washington Park’s outdoor courts for eight years, he told the crowd of hundreds, and he hadn’t seen much other activity except for “gang meetings on the courts.” He continued: “In the middle of July, six days out of seven, my organization is the only one doing work in the park. So to all the opposers, when was the last time you walked your dog in Washington Park? Because I didn’t see you. When was the last time you held a picnic in the park? Because I didn’t see you. This conversation should not be about preservation of parkland, but it should be about increased utilization of parkland.”

Murray was one in a long line of speakers, yet his plea stood apart for its bluntness and passion. “Brutally honest,” says Murray. “That’s usually what you’ll get from me.”

Murray is on a break from a lesson at XS Tennis when he gets a text that makes him shake his head. A coach at a major Southern university is inquiring about one of Murray’s players, one who happens to be getting a lesson at the moment: Isabella Lorenzini, a junior at Hinsdale Central High School.

Unlike most of Murray’s students, Lorenzini is white and hails from the western suburbs. She is also the best female high school player in Illinois. Just a few days earlier, she had won the state singles championship. As Murray’s reputation has grown, he has attracted more students like Lorenzini, who pays the full $80 hourly rate. “It used to be that to find a good coach, black tennis players had to commute out to the suburbs,” Murray says. “Now there are white people from out there coming this way. I love that they drive right by tennis facilities in Hinsdale and Oak Park and wherever else to come here, to the South Side.”

Murray tends to steer these kids toward earlier lesson times within the 3 to 7 p.m. slot he reserves for XS students on weekdays. His more underprivileged pupils, he reasons, come from single-parent or dual-working-parent households and need the added flexibility that evening hours provide. His heart clearly belongs to these students. He is downright gleeful when they beat more privileged players in tournaments. “Sometimes my kid will be working hard to win, and you can see it in that tennis brat’s face: Why are you working so hard to beat me? You’re supposed to just roll over and I’m supposed to win because things are supposed to go my way,” he says. (After winning the state championship, Lorenzini texted Murray: “Am I your favorite NOW?”)

As Murray reads the college coach’s text again, a sneer runs across his face. “Can you believe this guy?” he says. “Forget him. Just forget him.”

The coach was asking if he could come to Chicago to meet Lorenzini. Ranked in the top 30 nationally, she can have her pick of scholarships from almost any university with a tennis program. She won’t need a dozen phone calls from Murray, the way Hill did. She won’t even need one.

A few silent moments pass before Murray looks up from his phone and fixes his eyes on Lorenzini. “This guy didn’t have the courtesy to inquire about my less advantaged minority kids when I asked—he couldn’t get himself on a plane to Chicago for them—so I won’t be giving him the courtesy of returning this text,” Murray says. “Fuck him.”

When it comes down to it, Murray is building a sprawling tennis center on the former site of a public housing project not for the Isabella Lorenzinis of the world, but for the Steven Hills.

“Isabella’s future is defined: She is headed wherever she wants, and she will be great when she gets there,” Murray says. “But my minority kids, they just need a chance—one look, one ounce of access—and then you never know how great they can be.”