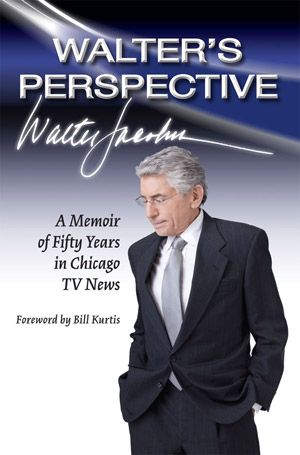

Walter Jacobson was often lampooned—think Mike Royko—and sometimes deservedly so, but he was also a scrappy, indefatigable (if occasionally sneaky in service of a scoop) newsman. His life story, Walter’s Perspective: A Memoir of Fifty Years in Chicago TV News, is as lively and jumpy as its author’s on-screen presence. At age 75 he’s still on air and still paired with the stentorian-toned Bill Kurtis, who writes the book’s foreward and claims the two never had an argument. If you care to catch their act, do so soon, because the bosses at WBBM-TV have already announced their retirement this February.

Walter Jacobson was often lampooned—think Mike Royko—and sometimes deservedly so, but he was also a scrappy, indefatigable (if occasionally sneaky in service of a scoop) newsman. His life story, Walter’s Perspective: A Memoir of Fifty Years in Chicago TV News, is as lively and jumpy as its author’s on-screen presence. At age 75 he’s still on air and still paired with the stentorian-toned Bill Kurtis, who writes the book’s foreward and claims the two never had an argument. If you care to catch their act, do so soon, because the bosses at WBBM-TV have already announced their retirement this February.

I read an early copy of the slim book (181 pages), officially published next week by Southern Illinois University Press. (That it’s published by an Illinois-based press is not surprising. Walter is a genuine local; he tried once to get a spot on “60 Minutes,” but was rejected and never made it out of Chicago where his quirks, his nasal voice, his un-anchor-like excitability were accepted and promoted but never exported). Here’s just a sample of the best of Walter’s memories, many winningly self-deprecating.

* When he was 15 in 1952 he landed a job as Cubs batboy; his per game pay was $2.50. That didn’t cover his train fare from Glencoe where he lived in a tense household with his domineering mother and her “terrorizing tongue”—the source, he writes, of his need to “stick it to authority”—his insurance salesman father, and three younger siblings. He learned to love the camera from being the first to shake the hand of a home-run hitter “in front of a full house screaming with delight.” His duties were less glamorous: “soaping” the urinals and sinks and putting “dirty socks, jockstraps, and uniforms into the wash.” Looking to curry favor, he attempted to steal the opposing teams’ signals. He also counterfeited Cubs’ names on baseballs sold for $10 to unsuspecting fans.

* In the spring of 1958 he landed a job as legman for Daily News columnist Jack Mabley, who later helped young Walter get a job at the City News Bureau. While covering a fire he was outsmarted by a Daily News reporter who pretended to be a fire marshall and dispatched Walter into a burning building to get quotes from firemen on whether they thought the building would collapse. Covered with ash, he handed his sooty notebook to the supposed official, who rushed away with the quotes for his own story.

* His next gig was at the wire service UPI. Looking to “make a splash” and move up to a job at a daily—there were then four in Chicago—he assigned himself a story on the increase in shoplifting, and stole a pair of $30 sunglasses from Marshall Field’s. The two “beefy guys” who detained him were not impressed with his explanation of having gone under cover to get his story. A Field’s executive let him go, but when he returned to UPI, the general manager fired him.

* The young reporter was hired next by the Chicago American—in pre-Woodward and Bernstein days, reporting jobs were not hard to get and the American didn’t check his UPI reference. He happened to be in the County Building when the assessor dropped off a pile of news releases intended for distribution to all reporters. Walter stuffed them in his pocket and rushed back to his typewriter. He got the scoop about a tax increase. For that, and other things, he earned Royko’s lifelong enmity and the indelible nickname “Skippy.”

* In 1963 he moved to television, WBBM Channel 2, and in six months was promoted to reporter, but he was far from realizing his fantasy of being Walter Cronkite. When JFK died that November, Walter dreamed of being dispatched to Dallas but instead was sent, with a cameraman, to the Chicago Theater. Having been ensconced in the theater, moviegoers would not have heard of Kennedy’s death. Walter was ordered to get plenty of “shock and tears” as he stopped people and asked them how they felt about the news.

* His first shot at anchoring came when he was at the WBBM studio on a Sunday afternoon, dressed in shorts and a t-shirt, and the anchorman called in sick. He had never been before a “live camera,” had no experience with a “teleprompter or lights, microphones, floors directors or commands in my ears….” He found a dirty, way-too-big shirt, a wide, ugly polka dot tie, and a stage hand put bricks under his feet to solve the problem of the anchor desk being up to his chest. Unable to get sound from the mic attached to his tie, with seconds to airtime, he was ordered to “drop your drawers,” so they could use a “rectal” mic.”

* He was soon assigned to write, produce and anchor a Sunday newscast, and he showed moxie by adding live interviews to his program—for example, an interview with Muhammad Ali about his refusal to serve in the U.S. army.

* WBBM fired him in 1971 because, Jacobson speculates, his analysis had become too strong. He moved to WMAQ. In 1973 he was hired back at WBBM to anchor the 6 and 10 o’clock news and to lift last place Channel 2 from the ratings basement. “We’re going to make you a star,” the CBS executive promised; he was paired with Bill Kurtis. The point, they’re told, is to have an anchor team of newsmen, not news readers, and “distinctly different personalities….. Bill the mature and fatherly figure. Me the saucy young kid….” (Jacobson is actually four years old than Kurtis.) When Jacobson signed on, his salary was boosted to $55,000 from $25,000. His “Perspectives” proved popular and the newscasts’ ratings improved. By 1979 the 10 o’clock segment was in first place.

* Walter reveals in this memoir time and again that he’s paid less than Kurtis, significantly less. Eventually both anchors make more than $800,000 a year.

* Both Kurtis and Jacobson get foreign assignments not typical of local news shops. In the fall of 1978 Jacobson went to Poland and was presented with the choice of interviewing Lech Walesa, the Solidarity hero to so many Chicago Poles, or the less known Archbishop of Krakow, Karol Cardinal Wojtyla, mentioned as the successor to Pope John Paul, who had died two weeks earlier. Jacobson chose Walesa and learned the next morning that Karol Cardinal Wojtyla has been named Pope—his “biggest and worst mistake in 50 years of journalism.”

* Not a mistake but an embarrassment was his and CBS’s guilty conviction in 1985 in a libel suit brought by tobacco company Brown and Williamson. Walter had delivered a “Perspective” labeling B & W executives “liars” for their denial of a campaign—designed by an ad agency and implemented by B & W—to hook “young starters” on cigarettes by making smoking seem cool and glamorous. As the jury selection was underway, Walter recognized that the selected jury members didn't like him.

* Royko described Jacobson in his column as “wee, wee Walter”; Walter retaliated by, after following an anonymous tip, reporting that the “flat-above-a-tavern” Royko lived in a fancy condo on Lake Shore Drive.

* After 20 years, Walter’s welcome at Channel 2 wears out; he’s removed from anchoring and his “Perspective” is put on hold. A boycott of the station by the Rev. Jesse Jackson hurts and Channel 2 is again in last place. That’s when the news manager, desperate for a boost, puts Walter in heavy homeless-man makeup—yellowed teeth, a “knotted beard” pasted on his face—outfits him in filthy, tattered, oversized clothes, and leaves him and a cameraman for much of a 48-hour-span in sub-zero February Chicago. They slept, at times, in a box on Lower Wacker. It’s a ratings boost, but just temporarily. So his boss tells him to get an interview with death row serial killer John Wayne Gacy. (Gacy agrees to see Walter, the former Cubs batboy, because Gacy is a lifelong Cubs fan.) The boss had promised Walter that if he carried off this dicey assignment he’d give him back his “Perspective.” Walter and his cameraman travel to the prison and Gacy, seeming to forget that he is still proclaiming his innocence, borrows Walter’s pencil to show how he strangled his victims. “I have pure gold," Walter thinks, “just in time for the February sweeps.” The Gacy interview plays over five nights and ratings double, but the boss doesn’t keep his promise to restore “Perspective.”

* It’s 1993 and 56-year-old Walter wants out of Channel 2, ending up at Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News at half his salary. But he’ll get to do his “Perspective.” After 13 years, in 2006, he’s out at Fox, replaced by a much younger man. He’s settled into retirement, still not using a computer, when the Channel 2 news director teams him and Kurtis for a nostalgic return. It seems to work, and about two years ago they’re signed to do the news at six; a gig which will end, not by their choice, in February 2013. Their replacements will be a much younger duo.