Photo: Jason Lindsey

One of Team Judson’s lung-busting early-morning rides along Sheridan Road

On an unseasonably cold Saturday morning in May, the sunlight is still thin and the streets of Evanston are nearly empty, aside from the occasional bleary-eyed dog walker or jogger. But inside the Starbucks on Dempster, 20 wide-awake cyclists are engaging in their weekly preride ritual.

Sipping coffee, they’re decked out from helmet to bib shorts in fluorescent formfitting materials that leave far too little to the imagination. There’s lots of backslapping, loud greetings, and joking around. Cycling shoes clack across the floor like a recital of tap dancers. These are the men (yes, on this day they’re all men) of Team Judson, one of the most hardcore groups of long-distance bicyclists in the Chicago area.

Although they might look the part—from their wiry builds and toned baby-bottom-smooth legs (the better to reduce drag) to their team uniforms (called kits)—and some race competitively, they aren’t pro cyclists. The tight-knit group includes CEOs, engineers, lawyers, a college administrator, and a brain surgeon. Gray hair is not in short supply: Most of these guys are baby boomers or older Gen-Xers with plenty to spend on bikes that can cost as much as cars.

“Who invited winter to stay around? It’s May,” says one rider, complaining about the 46-degree temperature.

“Man the fuck up!” another shoots back with a grin.

As the clock nears 7:30, the men toss out their cups and file outside to the line of shiny bicycles leaned up against parking meters and planters. These aren’t your average Schwinns. No self-respecting Team Judson cyclist would be caught dead riding a basic off-the-rack road model. For many, it’s a customized, ultra-accessorized bike that costs at least $10,000. While bespoke bikes give a performance edge, they’re also status symbols, like luxury cars or fine jewelry.

The riders’ teasing turns to Todd Wiener, 52, a lean environmental lawyer who cofounded Team Judson back in 1989. “You’re not really going to ride that, are you, Todd?” someone says with mock disapproval about Wiener’s bike, a model that was in style about 10 years ago.

“I have to!” replies Wiener defensively. “My other bike’s on the way back from Asheville!” (He had gone to North Carolina for a ride a few days earlier.)

The riders straddle their bikes, adjust their gloves and helmets, and fiddle with their bike computers. Then they push off from the curb and take off down the street. Within moments they’re speeding away, bunched together like a swarm of bees, the clicking of gears filling the air. Their destination: maybe as far as Kenosha, Wisconsin, 50-plus miles away. Maybe farther.

As they pedal north along Sheridan Road for their roughly three-hour rides, other cycling groups like theirs often merge with them. For around Chicago—and especially in the North Shore—group long-distance biking has become all the rage. Ethan Spotts, marketing director of the Active Transportation Alliance (formerly the Chicagoland Bicycle Federation), estimates that there are 200 cycling groups across the area, many of which have sponsorship ties with high-end bike shops. (Team Judson isn’t linked to any store.)

While the routes, intensity, and distances differ, the most serious of these groups share one thing: the near obsessiveness of their members. They have become hooked on cycling as a way to stay in shape, to relieve stress, and to experience the twin joys of competition and camaraderie. “There’s definitely a social component to it, and a real sense of community,” says wire-thin Judson regular Cliff Golz, 37, the assistant dean of students at Loyola University.

In so many respects—the opportunities for social and professional networking; the large time commitment that can leave spouses crying foul; and, of course, the cost—cycling is the new golf.

* * *

To get a better sense of what drives this breed of hardcore gearheads, I decided to take a ride with Team Judson, which for years has been the most intense cycling club in the Chicago area. “When we started, it was just me and my neighbor,” recalls Wiener, who lives in Evanston. “Then a few friends joined us, and it just grew and grew. Slowly it became big, with a lot of new people who came from all over to ride.”

On that chilly May morning, Wiener and company eye me incredulously as I pull up to the Evanston Starbucks on my beat-up 15-year-old Trek hybrid.

“Let’s see,” Wiener says, looking me over skeptically. “Mountain bike shoes, mountain bike helmet, commuter bike, unshaven legs. You look like a civilian.”

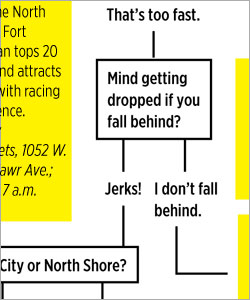

SO YOU THINK YOU CAN BIKE? This decision tree can find the group ride that’s right for you. Click the image to view the full version.

I assure him that, appearances aside, I can hold my own. Heck, I ran a 4:44 mile back in the day. I once cycled 112 miles on an epic one-day ride on New Zealand’s South Island. Sure, that was 12 years—and about 15 pounds—ago. But still.

Wiener remains unconvinced. “Just stay in the back,” he cautions.

I hang with the group as we head north on Hinman Avenue, soon reaching Sheridan Road. After a few blocks, I glance at my bike computer and see my speed steadily edge upward. Twelve miles per hour. Fourteen. Seventeen.

Maybe it’s the endorphins starting to kick in, but as I pedal, I think: This just might be the start of a brand-new me. From now on I’ll start getting up at sunrise to cycle 50 miles before work. Perhaps I’ll join a group like Judson—maybe a second one, too. My sad, flabby belly will soon become taut. I’ll shave my legs without a second thought.

But this fantasy is shattered within minutes as a dizzying succession of riders whiz by me. I try to keep up, going 23 miles per hour by now. My lungs are burning, and my shoes seem to be made of cement. I push harder on the pedals, but it is as if I am riding a 10-foot unicycle. The pack pulls farther away. Soon they are gone, leaving me alone on Sheridan. I had made it exactly 1.88 miles with Team Judson.

I console myself on the way home with a doughnut—OK, two—from Bennison’s Bakery. Wiener later tells me that I had made it about halfway through their warm-up.

* * *

As I learned the hard way, serious cycling groups aren’t for casual riders. You know when you’re on your bike and feel like you’re cruising really fast? You’re probably going around 17 or 18 miles per hour. Team Judson members average 23 miles per hour and can cover more than 100 miles per ride.

Some avid cyclists prefer a more leisurely pace—as does Todd Ricketts, 43, who co-owns the Higher Gear bicycle shops in Wilmette and Highland Park and often takes 25-mile-plus rides. (For more on him and his family, see “The Ricketts Family Owns the Chicago Cubs: Who Are These People?”.) “I like to get out and ride, but I’m not like these other riders,” he says. “They just get hooked.”

Even some Judson regulars can’t always hack the pace. “Usually [only] about one out of every three people finishes with the main group,” says Andy Spatz, 63, an Evanston architect and real-estate developer who has been riding with Team Judson for more than 20 years. “People just get spit out the back.” (This intensity is why Judson rides often draw professional racers who are competing in the area.)

It took Golz several tries before he was finally able to stick with Team Judson. He began cycling ten years ago after letting his health go. “I was living in Minnesota,” he recalls. “A Taco Bell was just across the parking lot, and I ate there all the time. I put on about 25 pounds in a year and a half.”

After moving to Chicago in 2003, he eventually fell into a routine of 35-mile loops along the lakefront. Believing he was ready for the big leagues, he joined Team Judson. Like me, he didn’t last long. “I found out that when you think you’re getting serious, you’re actually not even close to getting serious,” he says, chuckling.

He upped his regimen and now rides with Team Judson on weekends—on top of his daily 35-mile rides during the week.

For bicyclists who can’t keep up with the Judson crowd (that is, almost every person on the planet), there’s a host of other group rides out there, such as the Mafia Ride, which the website

Chicago Bike Racing describes as “not for the inexperienced,” and XXX, a serious group that cycles from Wicker Park to Highland Park and then splits up based on ability. There are others with more quirky sobriquets, including Gruppo Tu Earlio, which goes on several rides a week from Highland Park to as far away as Barrington, and the emphatically named Endure It, which rides 75-plus miles weekly from Naperville through such suburbs as Wheaton, Elburn, and Batavia. (To see which group might be right for you, see “Think You Can Bike?,” above.)

Several of these clubs travel great distances at speeds not far off Team Judson’s lung-busting pace. Others are less rigorous. For example, the Chicago Cycling Club’s top speed is around 10 miles per hour, and its rides end with a communal pancake breakfast. And although Team Judson is primarily populated by men, there are several rides geared toward women, such as Alberto’s Cycles’ on Wednesdays in Highland Park and Higher Gear’s on Tuesdays and Wednesdays in Wilmette and Highland Park.

These cycling groups fan out across Chicago, though many meet around the North Shore and head north through towns such as Glencoe and Lake Forest, and even farther. Why there? For starters, the scenic roads lined with tony homes offer riders nice eye candy along the way. Groups of bicyclists can’t get enough of the picturesque Lake Michigan route, with stretches of steep hills (by Midwestern standards) and sharp curves (which many riders take at more than 20 miles per hour).

Plus, the North Shore is filled with classic overachiever types. “People who are into cycling tend to be pretty driven in their life, so they’re driven in their cycling, too—they’re that type A personality,” says Mark Winston, a 48-year-old owner of a pest control company, who regularly rides with four to five groups. He recently rose before 3 a.m., cycled from his Skokie home to Milwaukee, hooked up with a different ride from Milwaukee to Madison (some 80 miles farther), and then rode back to Milwaukee—totaling about 250 miles in one day. “He’s a very sick man,” one Team Judson rider says admiringly.

Adam Keyser knows the feeling. The 42-year-old from Highland Park, who works in real estate, rides as often as six days a week, and even that is barely enough for him. His main riding group—he’s a regular in three—is called WGAS (Who Gives a Shit), but the acronym is obviously misleading—he clearly gives a, well, you know what. “If there’s a day and it’s beautiful and I don’t get a bike ride in, it upsets me, and I think about it all day,” says Keyser. “It’s a bit of an addiction.”

* * *

At Get a Grip Cycles, a bike shop in Old Irving Park that caters to the serious cycling crowd, bike frames and wheels hang from the ceiling with tiny white tags listing gigantic prices. Get this: A Mavic Cosmic CXR 80 front wheel—one wheel!—retails for $1,300. A Litespeed M1 carbon-based bike will set you back about $2,000, while a Serotta Ottrott frame runs $7,200. Adam Kaplan, the shop’s head bike technician, can put together a Parlee Z-O customized to your body and your riding style that may cost upward of $22,000, depending on the components you choose. (See “Anatomy of a $21,776 Bike.”)

“With bicycles, you can actually buy something that’s the best in the world,” says Kaplan. “You can’t do that with a boat or with a car. But there are bikes here that are better than what they’re riding in the Tour de France.”

Sure, the prices are mind-boggling. But after talking to Kaplan a bit—he explains how ultralight carbon frames provide stability, good handling, and require less energy to ride, how custom-made models are fitted for comfort (which can alleviate back pain), and how electronic derailleurs make shifting a breeze—I find myself thinking, Hmmm, maybe $5,000 for a bike is a pretty good deal.

It’s true that the lighter the bike—even a few hundred grams can make a difference—the faster you can go. As a general rule, as the weight of a bike decreases, the price increases. Then there are aerodynamics. “Lightness is a great bragging point, but being aerodynamic is the more important factor,” says Kaplan. “As you approach your threshold—as fast as you can go without blowing up—your wind resistance increases geometrically. So you need equipment that slices through the air more efficiently.”

Like cars, racing bicycles confer varying degrees of status. Team Judson’s website includes a humorous explanation (if bike humor is your thing) of what a cyclist’s choice of ride says about him. A Kestrel? “You are old, and so is your bike.” A Trek OCLV? “You are cheap.” A Merlin? “You are either an attorney or a dentist [who bought] a bike instead of paying for college for your kid.”

As for a Parlee, Rahm Emanuel, who owns one, has called it his “midlife crisis bicycle.” (Kaplan estimates the mayor’s off-the-shelf model cost around $8,000.)

Extra components and gear—from staples (helmets, gloves, shoes) to electronics (GPS, digital navigation, blinding lights for nighttime rides)—add up fast too. A wind-resistant bodysuit can cost $350. A pair of Assos Zegho shades retail for around $400. Don’t even get me started on the shoes. “You can go to any sports store and buy a bike helmet for 40 or 50 bucks,” says Keyser. “I just got a new one—I paid $180.” The difference? “It’s lighter, and it’s designed with more venting to cool you off for longer rides. And . . . it looks a little cooler.”

The high-tech gadgets are the real showstoppers. For Team Judson riders, for example, a power meter (cost: $800 to $3,600) is de rigueur. It attaches to your bike’s shifting system and tracks your speed, distance, and watts expended (a way for cyclists to see the amount of energy they exert). The more hardcore riders then download that information and send it to their coaches, who use it to customize workouts for them.

“It is expensive to have the supertrick, pro-caliber stuff,” Kaplan acknowledges. “But when your bike is truly a reflection of you, the combination of bike and rider is poetry in motion.”

* * *

When asked how his wife feels about his time-consuming riding regimen—he bikes five to six days a week, in total about 20 hours—Winston, a father of three, pauses and thinks carefully about how to answer. “It’s a little . . . difficult for her,” he says. “Over the years, she’s learned to deal with it. [But] it’s a thorn in her side.”

Let’s face it: Beyond the threat to marital harmony, the whole sport can seem just a little bit insane. Grown men shaving their legs to lessen wind resistance by an infinitesimal amount and spending five times more on a bike than the typical Bangladeshi worker earns in a year? To some, this may seem like just a male-bonding ritual among a tribe of hyper-competitive personalities with too much disposable income.

But ask yourself this: Do you love anything as much as these guys love cycling? What are you doing at 7 a.m. on a Sunday morning? When was the last time you tried to find your physical limits?

Just as Cheers was more than a bar, Team Judson is more than a bunch of middle-aged Lance Armstrong wannabes. It’s about the joy—the pure exhilaration—of propelling yourself down the street with no engine or transmission to drive you. It’s just you, two spinning wheels, your friends, and the open road. “It’s pretty simple,” Golz explains. “You step out the front door with your bike, and the world is yours.”