The email hit my inbox late one afternoon in early February, the sender someone named Monroe Smith, the subject line stating, “Marion is nearing the end.” I opened it and read:

Bryan,

Marion’s health has taken a serious turn for the worse in the last couple of weeks and this weekend he was transferred to Hospice Care. He could pass at anytime and is unlikely to last more than a week or so.

If you would prefer to call me or have me email you more details of his current condition or an update upon passing, I will be happy to do so.

He is suffering so we are hoping for him to pass quickly.

Monroe. It took a moment. How did he get my email address? I wondered.

Marion I knew instantly—although he, too, was a stranger in many ways. And I’d always heard him referred to as Rho.

That’s what my mother called him when she mentioned him, which, given the emotional agony and raw anger such occasions triggered, she rarely did.

She brought him up so infrequently, in fact, and I thought about him so little that I sometimes forgot that Rho was also my middle name. And that Marion, the man who lay dying, was my father.

It had been 18 years since I’d seen him. He had made the trip then from Fort Myers, Florida, where he’d lived for several decades, for a broadcast convention at the Moody Bible Institute here in Chicago. We met for dinner.

Before that, it had been 20 years. And that was it—exactly two encounters in my adult life after he and my mother, Jo, divorced when I was 2 and my sister, Tricia, was 4.

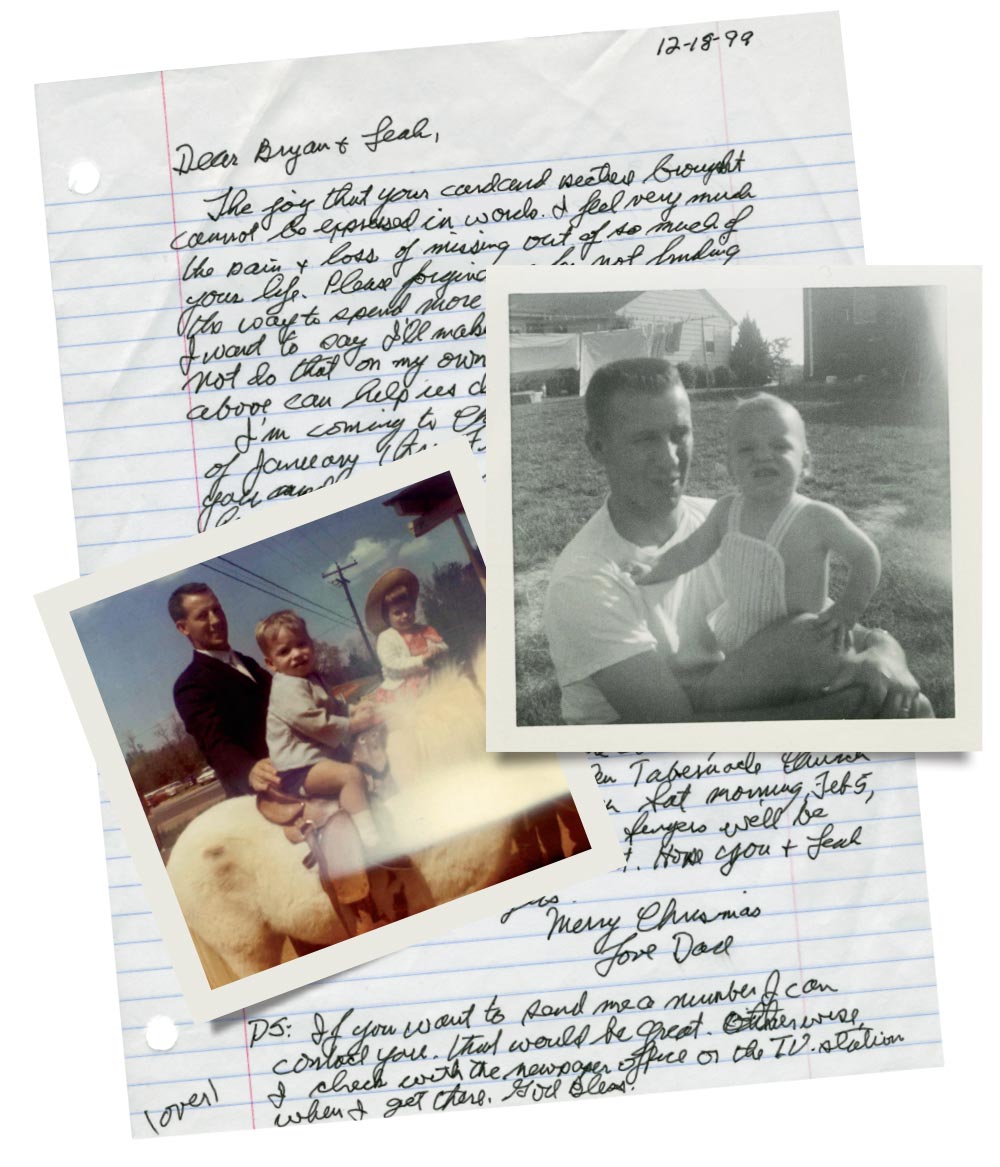

Over the years, he would occasionally send me long letters, always scribbled in a hard-to-read scrawl, always on lined white or yellow legal paper. Invariably, they brimmed with unsolicited advice, testimonials to the wonders of a born-again life dedicated to Jesus (“Have you accepted Him as your savior, son, because he is the only way. What church are you going to?”), or, in one case, a long and bizarre rant about the Masons and how I should be careful because I was in the Something Degree of Something-Something and that could spell big trouble for me. Always, always, without fail, they were signed “Love, Dad.”

I resented it. All of it. Love? We barely knew each other. Dad? That was a term of endearment, like “pop” or “pa” or “my old man”—not earned, exactly, but not conferred by blood alone either. Yes, he was my biological father, but he wasn’t my dad.

My stepfather, George, was Dad.

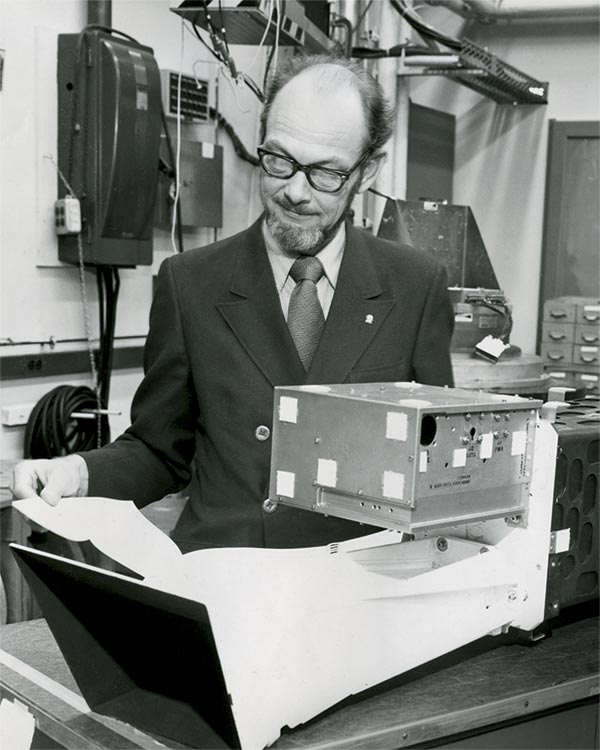

Skinny and bespectacled, genial and urbane, George Engle was a somewhat eccentric David Niven type who carried an elegant black leather cigarette case trimmed in brass and drove a black Volkswagen Beetle, which he kept polished to a high sheen.

He had puttered into our lives like an angel in a Hallmark drama who falls for a mortal and is granted special dispensation to return to Earth to be with his beloved.

With him, I didn’t have to yearn for the type of dad I had always wanted. George was, simply put, a kind, wonderful, gentle man. He didn’t cut the same imposing physical figure as my biological father. George was literally a rocket scientist—a space engineer for NASA—and he looked the part, complete with pocket protector, horn-rimmed glasses, and silver-threaded beard. Rho played football; George played chess.

Oh, how I loved him.

I had taken part in their wedding ceremony—a 6-year-old with a crewcut. Sporting a tiny tux and thin black bow tie, I conveyed the rings on a pillow down the aisle, too young to be anything other than giddy. As family lore has it, after the nuptials, I took George by the hand, looked up at him, and asked if it was OK to call him Dad now. My uncles tied cans to his Beetle and, using white shoe polish, wrote “Just Friends” on the back window as a joke.

He came to all my basketball games at the Laurel Boys and Girls Club in Maryland, even when I sometimes wished he wouldn’t. There he’d be, skinny as a scarecrow, legs double-crossed, pipe clamped between his teeth, wearing a lime-green leisure suit out of which sprouted an ascot that didn’t quite cover a bobbing Adam’s apple. He’d cheer at the wrong times, for the wrong things. I’d glance over and wince—until the time I made a silly, impossible shot, falling onto my butt as the ball rose toward the rafters, plunged back down, and ripped through the net with a loud swish. I glanced over and saw his shoulders shaking with laughter, his face lit up by the biggest smile I’d ever seen him wear. I loved him so much in that moment I’d have licked any kid who said a word against him, no matter how many times he wore yellow—yes, yellow—shoes or cheered the halftime buzzer for no good reason.

The thing I loved most about George was how much joy he gave my mother. She’d had a tough life—really tough—the result of a number of catastrophic experiences with men, including her father and stepfather and especially Rho, during their brief, tumultuous marriage.

In George, she had found a soulmate. He adored my mother, and she lavished him with the kind of affection that Frank Capra might have found schmaltzy.

And then, after nine years in our lives, he died. Lung cancer. Seven months from diagnosis to death.

During World War II, he had suffered terrible wounds to his chest while fighting in the Battle of the Bulge, and he’d also contracted a near-fatal case of tuberculosis. When he returned to the States, his discharge papers said this 5-foot-10 man weighed only 139 pounds. I wear the dog tag today that was cut from his neck in the hospital, the metal of it singed black. I keep his medals, including a service medallion with four bronze stars and the brass sergeant’s bars he wore, in a small black box marked “George.”

Injury aside, George had been lucky. The man next to him in his foxhole had been killed by the same grenade that tore through George’s chest. It’s my mom’s theory that the scar tissue from George’s wounds somehow metastasized into the cancerous lesions that would bleed through his dressings in his waning days. Maybe she was right. It didn’t really matter. He was gone. Dad was gone.

What memories I had of my biological father—and there weren’t many—could not have been more different from the ones I had of George. Through the fog of decades, I have only vague impressions of someone who was hard. Stern. Cold. Severe.

He scared me. He scared my sister, too. And my mother.

My mom always told me she married him for the same reason many young women wed men they weren’t sure about: She wanted to escape her hard upbringing, start a new life, sweep away the ugliness and replace it with a storybook romance, with my father the shining knight who would rescue her from her dark past.

In casting her fantasy, she could not have found a more perfect leading man. He played football in college—tiny Capital University outside Columbus, Ohio, but still. He was tall and strong and handsome and manly.

How he got the nickname Rho—the 17th letter of the Greek alphabet, as my mother often reminds me—remains a family mystery. But she apparently liked it enough to pass it along to me.

She says she only went out with him because a friend bet her she couldn’t. Judging from photos, I would have put my money on her.

My mother was a beauty—a homecoming queen and cheerleader, Norma Jeane Baker before she was Marilyn Monroe.

They were, if based on looks alone, the perfect couple, as handsome as bride and groom figurines atop a wedding cake. I have a photo of the ceremony. My mother’s wedding gown is magnificent. It flows like a lace and satin waterfall, cascading down in sweeping folds, pooling at the bottom like milk froth in an alabaster basin. My father looked dashing in a custom-tailored white tuxedo jacket, his hair in his signature crewcut.

Their happiness did not last past their wedding night. From then on, she says, she knew it was all wrong; from then on, she feared him.

She was determined to make it work, however. Somehow they managed to stay together nine years, long enough to have my sister, then me. My mother stayed at home while my father earned his bachelor’s degree in business, the precursor to a 50-some-year never-quite-successful career as an insurance underwriter for Travelers.

My mom recalls how I nearly died in the first weeks after I was born, my insides twisted by an undiagnosed double hernia. As she tells it, I was clearly in agony, wailing far beyond the normal cries of an infant, but my father refused to allow her to take me to the hospital. She spirited me off one day while he was out golfing. He kept playing even after he learned I would be undergoing surgery.

A couple of years later, as a cure for my childhood fear of the dark, he locked me in a closet.

Such were the stories I heard, recited and rerecited by my mother about my father, stories of cruelty toward her, toward my sister, toward me. They are stories I have little reason to doubt, though they are sifted through the filter of my mother’s deep anger and hurt.

I myself have but one personal memory of him. My father had taken me for a pony ride at a small fair. Lashed to long boards connected like the spokes of a wheel, the creatures trudged bleakly around a dusty circle enclosed by a weathered split-rail fence. Looking back, I’m sure they were as docile as old hounds. At the time, to me at least, they loomed like monsters. All I could see when my father lifted me onto one was its teeth—large yellow chompers through which slithered a pink tongue. The beast kept turning its head back as if, I imagined, to bite me. I started to cry.

I remember my father being not just displeased with me, but disgusted. No matter how far I stretched out my arms to be lifted off, he remained unmoved. Stop crying. Sit there.

The divorce was quick and uncontested and a relief to both sides. A judge granted my mother full custody and ordered my father to pay child support. Opportunities to visit were at my mother’s discretion. Reluctantly, she would allow him to take us for a few hours every so often, but each time my sister and I would return so upset that she finally refused to let him see us anymore.

As it was, he remarried almost immediately—a woman named Marie. Eleven months later, they had the first of their three children in three years.

He made a few attempts to connect with my sister and me, but my mother would not have it. I was 19 the next time I saw my father—three years after George’s death. My sister had moved to Queens, and out of some sudden and consuming curiosity, she was determined to see him, what he was about. He agreed to travel from Florida to New York, where my sister was living. He brought his daughter from his second marriage, Michelle. I drove up from Maryland.

The visit was a disaster. To me, he was too loud, too pushy, too familiar too fast. To cite the most irksome example, he referred to himself throughout the visit in the third person as “your dad.”

Nearly as off-putting was a trip we took with him on the New York City subway. The unwritten rules of the subway are clear: Project a demeanor of studied nonchalance, stare down or straight ahead. My father, on the other hand, bounced in his seat like he was on a carnival ride. There he sat with his too-erect posture, his Pat Boone white bucks sticking out under loud plaid polyester golf pants, declaiming in a booming voice about Christianity (he was, by then, born again). I glanced up miserably, just in time to see people avert their eyes.

The rest of the weekend was similarly awkward, and after he left, Tricia vowed never to subject herself to another visit. I had little desire either, though a couple of weeks later, I did ask if he might send me some money to make my rent. He mailed a check for $150. It bounced.

Many years later, in 2000, came the visit to Chicago, where I had since moved. He and Marie were staying at the Claridge Hotel, and he wanted to get together for dinner.

I had built up a fantasy scenario of how that meeting might go—where both of us had changed and grown since the last encounter, where my father was no longer overbearing and overexuberant, hectoring me about Jesus or, before the first drink arrived (iced tea for him, now a teetotaler), laying out in detail the way he felt my life should be going, where I was failing, all the ways he knew better.

No, this time we would share a simple connection.

He would just listen to me—not interrupting, judiciously offering advice in the thoughtful, measured way of Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. Our eyes would fill as we realized that, beneath it all, we were just two men, a father and son, perfectly comfortable with one another.

There was, of course, nothing to suggest that would be the case. And in fact, the dinner would turn out quite the opposite. After some niceties, he launched into a lengthy defense of his actions when I was a child.

I didn’t want to hear it.

A few days after he left Chicago, his wife sent a letter, apologizing for him. “I know he came across quite ‘hard,’ ” Marie wrote, “but he’s truly not that way.”

The letter went on, but I was done. Like my sister before me, I vowed never to see him again.

In the years that followed, he would send me an email, sometimes a card, on almost all of my birthdays. Sometimes I responded; sometimes I couldn’t bring myself to. Mostly, I put him out of my mind—buried him, if you will—to the point that, in recent years, I almost forgot he existed.

I assumed that he had done the same, frankly, and I understood. He had his own family, three children to raise. Yeah, he sent the birthday notes and said he’d like to see me, but I figured it was just something to say, that he didn’t mean it.

I was wrong.

To the extent that I thought about it at all, I figured that when my father’s passing came, I would learn about it after the fact, maybe years after, getting word by happenstance. Don’t know if you heard, but Rho passed away.

Oh, I would respond, I’m sorry to hear.

Now I was reading and rereading Monroe’s email:

If you would prefer to call me or have me email you more details of his current condition or an update upon passing, I will be happy to do so.

Monroe was the older son from my father’s second marriage. Clearly, he wasn’t expecting me to come to Florida. And I never imagined I’d have the slightest desire.

Learning that the end was at hand, however, I wasn’t so sure. I imagined my father lying in his hospice bed. He was 84 now, this foggy figure from my past.

My mind roamed back to George. He’d had three daughters from his first marriage, daughters he had helped throughout their lives with both money and a place to live while they went to college. None of them thought to show up as he lay dying upstairs in that awful, yellow-walled bedroom, where my mom changed the bandages on his chest every day.

George never let on how much it hurt him for his daughters not to be there, but my mother knew. She was so angry that she actually bribed one of them to visit, which she did, once, briefly.

As the day wore on, that thought nagged at me. The possibility occurred to me that I had been lying to myself about a lot of things when it came to my biological father—most especially the sincerity of his desire to see me again. Dismissing it, I began to realize, was far easier than facing the truth—that I had built a narrative in my mind about how unbearable he was. Judgment had been passed and sentence handed down: I would withdraw from him, I would spurn him and his letters and his birthday cards and his proclamations of fatherly love. And I would convince myself that I was perfectly justified.

Now, however, something began to give in that carefully constructed wall of self-righteousness. Suddenly my inflexibility began to feel cruel. I knew he would be grateful to see me.

I wrote Monroe that evening. “I am thinking of coming down there, but I would like to connect with you before I finalize any plans. Could you call me?”

He did, and for the first time in my life, I chatted with one of my two half brothers. “I think I’m coming down,” I said.

My father—our father—had taken a bad fall a couple of weeks earlier, he explained. That itself wasn’t life-threatening. It was the cancer that had been spreading through his body. He was also experiencing some dementia—the result of two strokes in recent years.

He had proved remarkably resilient until the stumble. Now the doctors weren’t sure how much longer he would hang on. Days. Maybe a week. Maybe a bit longer.

When word reached Michelle, she called me, sobbing: “Bryan, he has never stopped loving you, never. He is so proud of you. Whenever he talks about how many children he has, he always says I have three sons and two daughters. I cannot tell you how much it would mean to him if you came.”

I hung up and sat for a moment.

I picked up my phone and booked the flight.

Time is precious as it runs out,” my mentor, the writer Jon Franklin, wrote in one of his most famous stories. That phrase kept running through my mind as I shifted in my seat, 40,000 feet up.

As did a Warren Zevon song, “Keep Me in Your Heart,” that I played several times over the next few days, including the two hours sealed in the plane:

When you get up in the mornin’ and you see that crazy sun

Keep me in your heart for a while

There’s a train leavin’ nightly called “When All Is Said and Done”

Keep me in your heart for a while

I can’t type those lyrics without getting misty, which gives you some idea of what the trip was like. I’d be sitting there on the plane, staring at the seat in front of me, when I’d feel a hot tear, then two, streak down my face. I dabbed my eyes with a cocktail napkin one of the flight attendants offered and tried to lose myself in other music less likely to slice my heart open.

I arrived in the early evening. The hospice center, a yellow Spanish revival trimmed in white and rust-colored tile, was set back behind palm trees and southern live oaks. It was late for visitors, and the only person I saw in the lobby was an elderly security guard at a desk flanked by white columns. I signed in and began winding through the camphor-scented hallways in search of room 208.

When I found it, I stopped short. I had rushed so urgently—the flight, the rental car, the hotel, directions, Waze—that only now did it dawn on me that I really was here and that Marion Smith, my father, really was on the other side of the door. I hadn’t the faintest idea what to expect. Michelle had texted that she would be waiting. Would we shake hands? Would she be wary? Would I? How would my father react? Would he recognize me? Would I be OK if he didn’t?

I took a deep breath. Then I knocked softly. A woman with straight blond hair and searching blue eyes opened the door. She immediately pulled me into a long hug. “I’m so glad you’re here,” Michelle whispered in a thick voice. “I told him you were coming. He was talking about it all day. You cannot imagine how excited he is to see you. Come on in.”

As I stepped into the room, I saw him. He lay at an angle in the soft orange light of a bedside lamp, a white hospital sheet pulled up to his chest, the television set attached to the wall in front of him murmuring. The room looked like a suite in a business hotel.

Michelle had warned me about his face, that the fall had left him looking like he’d been on the losing end of a bar fight. Sure enough, a black half crescent curved under his right socket. A blotch the size and color of an autumn leaf pinkened the area above and below his brow. His forehead gleamed with a black and purple bruise that I realized, when I looked carefully, was shaped like a large comma. He had a full head of silver hair, but it was wispy and uncombed, with little flyaways sprouting like tufts on a chick. He was, unmistakably, the Rho of my childhood, older, battered, dying, but the same.

He turned his head slowly as I took a seat in the chair Michelle had pulled up for me. His mouth had been a slash before, the corners turned down. When he saw me, his face lit up like a camera flash. “Oh!” he said. His voice was soft and high-pitched and gentle, not at all how I remembered it. “Praise God. Praise God.”

“This is Bryan, Daddy,” Michelle said. “He’s here. I told you he would come. God answered our prayers.”

My father’s eyes welled. He buried his face in his hands. “How are you, sir?” he said.

“Don’t worry, he calls every male ‘sir,’ ” Michelle whispered. “It’s his years in the military. He knows who you are.”

“You’re a writer!” he said. “I have read your stories. I can’t believe someone so important came to see little old me!” He covered his face again.

I didn’t know what to say. Of all the possibilities I had played out in my mind, his reaction, his unadulterated joy, was never one of them. It was heartbreaking—beautiful and deeply poignant. “It is good to see you,” I said.

I took his hand. It was soft as a baby’s, veined and mottled. “I heard you took a bad spill,” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “I was clumsy.” He tapped his head, as if to demonstrate, but he cried out from the pain, then smiled bashfully. “I forget sometimes.”

“I’m going to leave you two alone for a little while, if that’s OK,” Michelle said.

I nodded, my father’s hand still in mine. We sat there not saying much at first. At intervals, a hospice worker came in, fluffed my dad’s pillow, combed his hair.

I looked at him again. For so long he’d loomed as a villain, the boogeyman in a family story that had been told so many times that I could replay it in my mind like a film. The man before me now was at once the same and different. He was still excitable and chatty, but he was also docile, almost childlike.

“I can’t believe it,” he repeated, and began reciting a verse from the Bible about gratitude. Nearby, a picture of his second wife smiled out from a table. Marie had died a year earlier of cancer. I hadn’t known.

I asked if I could take a photo with him, and he smiled. “Yes, sir,” he said. “I would be honored.”

“I just wanted to tell you … ,” I said, pausing, unsure what to say. “I just wanted to tell you,” I began again, “that I’m so glad I’m here, too.”

He squeezed my hand. “How old are you?” he asked. “You’re 13, right?”

I laughed.

“I’m going to live to be 100!” he said, sitting up a bit straighter.

“I’m glad,” I said. “If you live to 100, that means I get to live to 100.”

“Yes, sir,” he said, and closed his eyes. I stroked his hand for a moment.

We talked a bit longer, about nothing in particular, and then both of us fell silent.

In the Hollywood version, this is where I would have said something like “I need you to know that I stayed away because you hurt me.” Or “I just wanted you to know that I forgive you.”

Instead, I held his hand and smiled, and he smiled back.

After a while, he said, “I’m very tired.”

“I’m sure,” I said. “I’ll get Michelle.”

I opened the door and waved her back in. She walked around to the side of the bed and stroked his hair. “You’ve had a big day,” she said. “Do you want to go to sleep now?”

He nodded but looked at me, as if he wanted me to stay.

“Don’t worry,” Michelle said. “Bryan will be back. He’s staying here a few days.”

“Praise God,” my father repeated.

I stood to leave but sat back down and took his hand once more. I looked at him and he looked back, directly into my eyes.

I could hardly choke the words out, but I said, “I love you, Dad.”

He smiled.

“I love you, too, son.”

I went to dinner with Michelle that evening, and we had a long talk about our lives. She told me about some health problems she’d been having and about her two daughters. Brooke—“our Brookie”—had died of a heart defect at 16, just three months before I’d met my father and Marie for dinner in Chicago; Michelle’s other daughter, Sierra, had been a handful, but of late the two had reached something of a mother-daughter détente.

Sierra, Michelle admitted, was wary of my visit. “You’re going to become attached to him, Mom,” she had told her. “And then he’s going to leave and be gone from your life again, and you’re going to be hurt.”

“I can understand that,” I said. “But I want to let you know that isn’t going to happen.” I meant it.

Michelle explained that neither she nor my father had ever given up hope that one day I would come visit. “We have loved you all these years,” she said, tearing up. She took my hand and looked me in the eyes. “He has loved you. You know that, right? Your father has always loved you.”

My father. My sister.

She continued: “He has loved Tricia, too, though I know she probably doesn’t feel like she’s able to come.” She wasn’t. She just couldn’t bring herself to do it.

“No,” I said. “But she knows I’m here, and she says she’s glad.”

My mother knew I was there, too, I explained. Hearing about Rho again had been painful for her. The mere mention of his name had stirred up feelings she had long buried. Still, she gave me her blessing: “I’m proud of you for doing it.”

Michelle paused for a moment, then gathered herself. “I want to say this with all respect,” she began. “About what happened between our dad and your mother …”

I stopped her. I didn’t want to hear it. Not out of some feeling of denial, but because for me, in that moment, it didn’t matter. Whatever happened, happened. “I’m here with an open heart and nothing but forgiveness,” I said. “I have no ill will toward anyone.”

The words surprised me. I hadn’t before articulated how I was feeling, why I wanted to be there, even to myself. It took me saying it to understand.

In the days that followed, I met my two brothers for the first time—Mike and Monroe—and one night we all went to the house Michelle shared with her longtime boyfriend, Jimmy. Sierra was there, too.

The evening was lovely. Comfortable. We laughed. I joked with Sierra—my niece. It felt like a family reunion, even though I had only just met all of them.

I suddenly had a baby sister and two kid brothers. I had inherited a family that already loved me, that had been waiting on me. For all the things my father had never given me, he had, in his final days, bequeathed a gift beyond measure.

My father rallied enough for me to return to Chicago. But after a couple of days, I received another email. This time, Monroe said, Marion might not last more than a day or two.

I flew back to Florida and sat with my father again, only this time, he was too heavily medicated to respond.

I left and went to my hotel. Five hours or so later, at just after 3 a.m., my cellphone buzzed. It was Michelle.

“Daddy is gone,” she said.

“Oh, Michelle…”

“But he’ll be here for a bit if you want to come say goodbye.”

I drove back to the hospice center and sat alone with his body for a time.

I shook my head and wept. For his passing, of course, but also from the sorrow of having stayed away so long.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m so sorry.”

I was a pallbearer at my father’s funeral, which took place in a small town on the outskirts of Nashville, the hometown of Marie, who had bought a plot for him.

Michelle gave the eulogy. She talked about a man I did not know, a flawed man to be sure, but a decent man in the end, who through his faith had shed much of his harshness. She spoke of his love of his recumbent bicycle, which the family had given him when he was in his 70s and on which he tootled about almost to the end.

After the service, we walked outside in the chilly gray afternoon.

My brothers and I carried the casket to the back of the hearse and then, at the cemetary, to the grave, beside which rose a mound of the freshly displaced earth. Some of the family sat under a small tent. By now a few drops of rain had fallen. I had been standing with my wife, but seeing Michelle alone as the pastor wound up his remarks, I walked over and put my arm around my sister, and she leaned onto my shoulder.

One by one, we took up a shovel provided for the purpose and threw a single load of dirt onto the polished casket. It skittered and spread, little pebbles in the soil making a sound like a spatter of rain striking a windshield. Then we walked, arm in arm, back to the church.