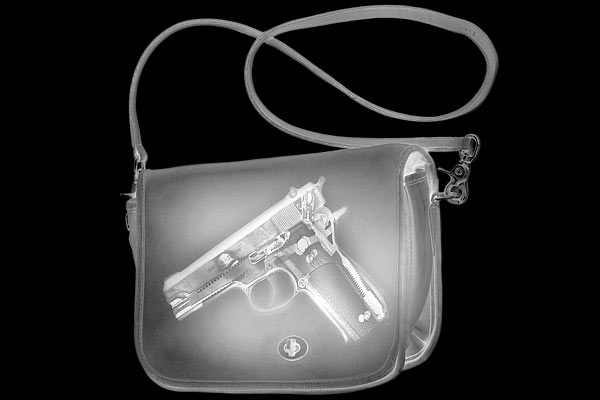

Photograph: Calysta Images/Tetra Images/Corbis

So it looks like Illinois now has to join the other 49 states and pass a law allowing ordinary citizens to carry concealed firearms. (Thanks a lot, Judge Posner.)

As the rest of the states’ concealed-carry laws demonstrate, there are lots of ways to do it. I’ve looked at them all. If legislators want to try to keep gun restrictions in Illinois as tight as possible, while still complying with Posner’s December order to undo the state’s ban on carrying concealed guns in public, here are a few suggestions.

Vet permit applicants like crazy.

Wayne LaPierre, the CEO of the National Rifle Association, has famously said: “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

But how do you determine who the good guys are? You can start by asking the cops, which New York and California do before granting any concealed-carry permits. In California, local police must confirm that applicants are not only felony-free but also of “good moral character.” New York requires applicants to provide character witnesses and a mental health history—and to have a “special need for self-protection.” These states are good models, says Jonathan Lowy, the lead lawyer with the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence: “They allow law enforcement to have a say in whether carrying would increase the danger to the public. Any system that forces law enforcement to issue to people they know are dangerous is a bad system.”

Sometimes, of course, good guys turn bad (Drew Peterson, anyone?). Good concealed-carry laws try to weed out those people too. For example, California, Texas, and Tennessee prevent anyone who is behind on child support payments from getting a permit. And to prevent chronic alcoholics from carrying, Florida won’t issue a permit to anyone who has been to court-ordered treatment within three years (or to anyone who has received two DWIs). Virginia and Louisiana extend that period to five years; Tennessee to ten.

Make them prove their gun skills.

I’m a pretty good guy—no DWIs, no rap sheet, no missed child support payments—but you wouldn’t want me packing heat, at least if my experience shooting (and badly missing) pop cans with a 12-gauge is any indication. I’d certainly need some practice first, and I’ll bet others would too.

Shooting is not unlike driving, points out Philip Cook, a criminologist at Duke University. You don’t need a license to own a car, but you do to drive it on public streets. “There has to be a demonstration of competence,” says Cook. “You have to have . . . regular reviews, and [a license] can be revoked for bad behavior.”

Tennessee and Texas are among the 30 or so states that require training before someone can get a concealed-carry permit. Tennessee requires four hours of classroom instruction and four hours on the firing range. Texas mandates ten to 15 hours of training. At the very least, Illinois should borrow one requirement from these states: If you aren’t 70 percent accurate in live-fire training, you don’t get a permit.

Ban gun toters from as many places as possible.

Returning to the car analogy: The state tightly restricts where you can drive. You can’t go for a spin in Grant Park or through Daley Plaza (even though the Blues Brothers did). And there are lots of private streets where only authorized people can go.

All states restrict the places that permit-holders can legally carry guns, to one degree or another. Utah, for one, is extremely permissive—concealed guns are allowed in public schools. Across the country, a patchwork of restrictions is more typical: 26 states let businesses turn away pistol-packing patrons. Others ban guns in sports arenas, hospitals, and polling places. Perhaps because some gamblers don’t know when fold ‘em, several states have banned them in casinos, like in Indiana.

Illinois should be as restrictive as possible—for example, opposing the local rifle association’s push to allow CTA riders to carry. That could cause some serious road rage.