On the morning in 1932 that cubs shortstop Billy Jurges was shot in the Hotel Carlos, the team was scheduled to play a home game against the Philadelphia Phillies. The scene of the crime was not a surprise. Over the years, Cubs players regularly rented rooms at the hotel, which was within easy walking distance of Wrigley Field and various nightspots. In addition to Jurges, outfielders Kiki Cuyler and Marv Gudat had rooms there for the season.

Jurges, born in the Bronx and raised in Brooklyn, was known for hard-nosed play and a fiery temperament. He had been signed in 1929 by Cubs scout Jack Doyle and was more skilled as a fielder than as a hitter. In 1931, he met a woman named Violet Popovich at a party. Tall and dark-haired, she had ambitions to break into show business. She liked ballplayers and was romantically linked with several from the National League, including Al López, the Dodgers’ catcher, and Leo Durocher, the shortstop for the Cincinnati Reds. Jurges and Popovich began dating, but the relationship soured. Jurges’s friends and teammates warned him to stay away from her, and he told her he wanted to break up. In June 1932, when the Cubs were in New York, Popovich called Jurges at his parents’ house in Brooklyn, and they argued.

Just before the Cubs were to return to town, Popovich rented her own room at the Hotel Carlos. Her plan was to confront Jurges on the morning of July 6.

That morning, Popovich sat at the desk in her hotel room, drinking gin and thinking about murder. She took out a piece of paper and wrote a note to her brother:

Dear Mike,

I have just a few minutes of waiting before I see Billy so I’ll write and try to explain everything. I know you’ll understand.

To me, life without Billy isn’t worth living, but why should I leave this earth alone. I’m going to take Billy with me. We are getting along famously, just as everything should go, but a few people like Ki-Ki Cuyler and Lew Steadman forgot there might be anything fine and beautiful in our love and dragged it in the mud. I know what I’m doing is best for me and I hate to do it … but???

My last wish is that mother, you, and the boys go to California and enjoy life to the greatest extent, and remember your father once in a while. I can’t write any more. I’m so nervous. I love all of you.

Violet

Popovich placed the letter on the desk, pushed a .25-caliber pistol into her purse, and walked out of the room. She called Jurges from a phone in the lobby and said she wanted to talk to him. Jurges was nonchalant. He said, “C’mon up.”

By the time Popovich got to room 509, she was agitated. She wanted to give Jurges one more chance, hoping he would reconsider. She took a deep breath and knocked. Jurges opened the door and let her in.

They had a brief conversation. She told Jurges that she didn’t want to break up. Years later, Jurges recalled how he had responded. “I’m not going to go out on any more dates,” he said. “We’ve got a chance to win the pennant. I’ve got to get my rest.”

Popovich asked for water. Jurges went to the bathroom, filled a glass, and brought it back to her.

At that point, Popovich pulled the gun from her purse and pointed it at her head. Jurges reacted immediately, lunging for the gun and trying to wrest it out of her hands. They struggled for control of the weapon. Three shots were fired: The first ripped into his right side, colliding with a rib. Another hit his left pinky. And the third penetrated Popovich’s left hand.

Popovich ran out of the room. Jurges stumbled into the hallway, bleeding, and tried to assess his wounds. There was a lot of blood. A terrifying thought rushed through his mind: I’m going to die.

Marv Gudat was in the lobby when he heard three sharp explosions coming from the vicinity of Jurges’s room. His first thought was that his teammate was setting off firecrackers. He rushed up the stairs to find him in the hallway, holding his side. “Get a doctor!” Jurges said.

Soon an ambulance screeched to a halt outside. After taking a quick look at the blood and the wounds, the doctor came to the same bleak conclusion that Jurges had: The ballplayer was probably dying. He told Jurges, “You’ve got it bad.”

Police officers located Popovich, who had returned to her room. She had suffered only a minor wound to her hand. The half-empty bottle of gin and the suicide note rested on the table.

Moments later, John Davis, the Cubs’ physician, arrived. Davis had a different impression of the severity of Jurges’s wounds. “You’ll live,” he said. After treating Jurges, Davis also looked at Popovich’s injury. Then the wounded lovers were escorted into the back of the ambulance. Sirens screaming, it raced to Illinois Masonic Hospital. A few hours later, Popovich was transferred to the Bridewell Hospital and, from there, to the Cook County Jail.

Word of the shooting spread quickly. A man on the street told Cubs infielder Woody English about it as English walked to Wrigley from his hotel a few blocks from the Hotel Carlos. When Davis got to the ballpark, he assured Jurges’s teammates that the shortstop would recover.

From his hospital bed, Jurges phoned his father and told him not to worry, that he would be OK. If the nurses let him, he probably listened to the Cubs game on the radio.

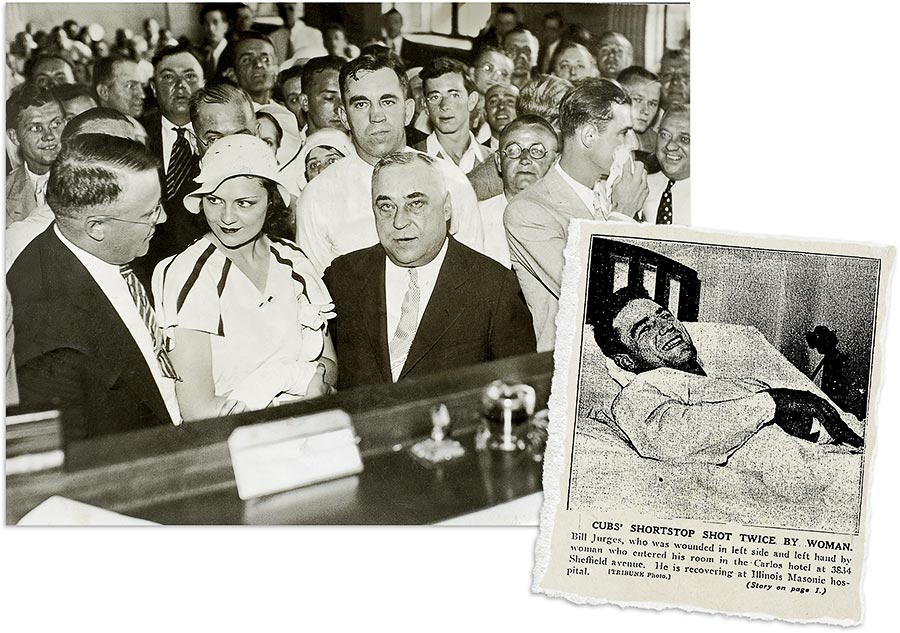

That evening a group of reporters and photographers was admitted to Jurges’s room. The player was photographed in bed, a slight smile on his face. Flashbulbs exploded around him as he patiently answered questions. He tried to downplay the incident, acknowledging that he was lucky to survive but stating that Popovich had come to his room to commit suicide, not to harm him.

Photos of Jurges in his white hospital gown appeared in the Chicago papers the next day. Newspapers around the country picked up the story and ran their own version of the events. The shooting was reported in the sports pages of the New York Times under the headline “Bill Jurges Wounded by Girl He Rejected.” Popovich was described as “a pretty brunette” and “a woman scorned.”

Jurges and Popovich saw each other in court on July 15. The courtroom was packed with spectators and newspapermen. Jurges arrived first, dressed in a suit and accompanied by Davis and Cubs pitcher Pat Malone. A few minutes later, Popovich entered. All heads turned in her direction. She wore a white crepe dress trimmed in red, a white hat, and red shoes, her left forearm covered in a bandage. She was stunning. The young woman offered a shy smile to the assorted onlookers.

The judge, John Sbarbaro, ordered Jurges and Popovich to stand before the bench. A photographer captured the scene: a debonair Jurges looking directly at Popovich, both of them smiling. Flanked by lawyers, they looked mischievous and slightly embarrassed, like young lovers who had been caught playing a prank.

Sbarbaro asked Jurges several questions about the shooting, which the shortstop answered with reluctance. Then Jurges said, “I have no desire to testify.”

“Do you think you will have no more trouble?” Sbarbaro asked.

“No,” said Jurges. “I wish to drop the case.”

Sbarbaro looked around the courtroom and sized up the situation. He took his time, giving the appearance of sober deliberation. “Then the case is dismissed for want of prosecution,” he said. “And I hope no more Cubs get shot.”

Moments later, outside the courtroom, Popovich summed up her feelings to reporters: “If I happen to see Bill again, it will just be impersonal.”

Jurges recovered quickly, returning to the Cubs lineup later that month. In August he drove in a game-winning run against the Boston Braves.

Two decades after the shooting, a writer named Bernard Malamud would recall its details as he sat in front of a typewriter trying to write his first book. The story of Jurges and Popovich would inspire a key scene in that novel, which he had titled The Natural.

As for Popovich, the incident briefly boosted her career. A few weeks after the shooting, she was starring in a new act. She used her stage name, Violet Valli, and billed herself as “the Girl Who Shot for Love.” An advertisement in the Chicago Daily Tribune described the show as a “screamingly funny burlesque production.” Its title: Bare Cub Follies.

Adapted from The Called Shot: Babe Ruth, the Chicago Cubs, and the Unforgettable Major League Baseball Season of 1932 by Thomas Wolf. Reprinted by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2020 by Thomas Wolf.