Chris Collins has a cold. A small botheration, to be sure, but nettlesome nonetheless, bedeviled as he is with regular volleys of small concussive sneezes and sniffles. “A little summer thing,” says the 34-year-old-looking 43-year-old between tissue dabs. “Sucks.”

Especially today, in early August, when he’s huddled with his Northwestern University basketball staff in his sun-dazzled corner office, brainstorming a sequel to last year’s blockbuster season, which enthralled not just Chicago but the nation for a few delicious weeks in March. In case you hadn’t heard, Collins and his team accomplished a feat considered only slightly less wondrous than the Cubs’ championship run. After 78 years of hapless, sometimes heartbreaking futility, Northwestern rode the head coach’s self-confidence to its first-ever appearance in the NCAA tournament. As if that weren’t enough, the Wildcats managed to actually win a game—in thrilling last-minute fashion—and then gave top-seed Gonzaga a bona fide scare in the second round.

To the Cinderellas go the spoils, which Northwestern certainly enjoyed this off-season. Collins was asked to throw out the first pitch at Wrigley Field. Team members strode the red carpet at the ESPY Awards, having been nominated for their full-court-pass buzzer-beater win over Michigan. Collins’s summer camp drew a record number of attendees, the kids awestruck by the coach and player-counselors who had previously toiled in anonymity but now, by dint of relentless ESPN coverage, were minor rock stars. And Northwestern counts the likes of alums Stephen Colbert and Julia Louis-Dreyfus among its suddenly blossoming fan base. (OK, the latter has a son on the team, but still.)

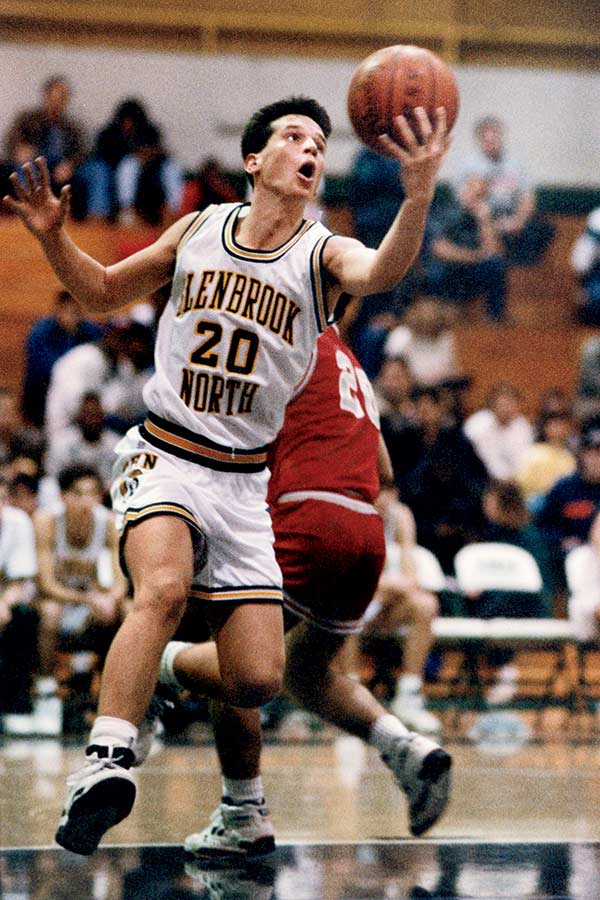

It is heady stuff for anyone—even Collins, who is used to such hoopla. He grew up as the son of longtime NBA player and coach Doug Collins, generated press as a schoolboy sensation at Glenbrook North, and played and was mentored at basketball juggernaut Duke under the legendary Mike Krzyzewski. “I’m a dreamer. I’ve always envisioned things—the kid in the backyard sinking the game-winning shot,” says Collins. “Then all of a sudden, you’re there and it’s real. It was emotional.”

So it would be understandable if Collins relaxed a bit and relished it all. Though he watched his 14-year-old son, Ryan, try out for his high school golf team and spent time with his wife, Kim, and 11-year-old daughter, Kate, also an athlete, Collins, if anything, drove himself and his coaching staff harder in the off-season.

His goals, of course, include far more than slipping into the tournament once; rather, he envisions a program of sustained excellence—a sort of Duke of the Midwest—where an NCAA berth is a given, not a history-making event, and where a top seed, even a championship, is not just talk.

“You have this big year, and part of you wants to kind of sit back,” Collins acknowledges. “But then you smack yourself in the face and remind yourself, No, that’s not what I’m about. We’ve got a lot more to do.”

And so, sniffles and all, Collins has hauled himself into the office this morning—more than eight weeks before his 2017–18 squad is officially even allowed to practice—surrounded by his staff, to trade notes on recruits, finalize blueprints for the team’s first workouts, float likely lineups, deliberate where new players will fit, how much court time they might get. But most of all, he’s here to hammer home the message he’s delivered since day one of the off-season: Last year, as wonderful as it was, is over. “What,” he asks rhetorically, “have you done for me lately?”

It’s easy now to see the whole thing as fate. That after a handful of near misses over the years, the team was bound to make the tournament eventually. And in hindsight, the Chris Collins narrative seems almost as pat: A young, dynamic, highly pedigreed go-getter takes the reins of a program with nowhere to go but up and reaches stupefying new heights within four years.

The reality, of course, is something far different—not so much a fairy-tale smooth ride as a wildly bumpy boat trip across a stormy Lake Michigan, full of crashing waves and narrowly averted capsizes. It was enough at times to shake the considerable faith of Collins. But he had something working in his favor, something fueling him: a relentless desire to escape the rather large shadow of his dad that has long loomed over him.

From appearances alone, it’s impossible not to link the two men. Both share the high foreheads, the lanky frames, the wide grins, and the faces that can cloud with intensity or anger in an instant. The son bears a striking resemblance to the late actor Bill Paxton in his Titanic days. The father leans more toward James Woods. In careers and coaching styles, however, they have followed different paths. Doug, the fiery, heart-on-the-sleeve, tough-love drill sergeant; Chris, the players’ coach who is not averse to lacing into his team when he feels it’s warranted but, at the same time, doesn’t mind cutting his players slack on chest bumps and small displays of cockiness.

If Chris Collins didn’t lead a charmed life as a boy, it was something close. He grew up in New Jersey, just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, where his father was a guard for the 76ers. Young Chris would toss footballs with Ron Jaworski, the Pro Bowl quarterback of the Eagles, and hang out with Bobby Clarke, the star center for the Flyers. Just up the street lived Mike Schmidt, the Phillies’ Hall of Fame third baseman. “To me, they were just dads,” Collins recalls.

The family moved to the Chicago area—to Northbrook—in 1986 when Doug, by then retired as a player, was hired to coach the Bulls. The roster included a third-year guard by the name of Michael Jordan. “I was like, Man, how cool is this?” recalls Collins, who was 12 at the time. So awestruck was he that he didn’t know how to react when the icon in the making shoved a box of new Air Jordans at him. Thinking it was a gift, he was putting the kicks in his bag when Jordan growled that he wanted them laced, not taken. In short order, Collins became the shoe king’s unofficial shoe handler.

He also had another gig. “I was the guy who used to sit under the basket, and when the players would fall down, I’d run out and wipe the floor up and then hustle back under the basket,” he says. “There are these great pictures and videos: Anytime the Bulls had a big win, my dad would give me a hug and we’d walk off the court together. It was really special.”

That was the good part of being a coach’s son. The other side? Constantly being coached. “It was an interesting dynamic,” says Collins, who first started playing basketball at around age 5.

“We’ve always been very close, but I used to take his coaching direction very personally. The moment he would turn and say something to me, I just couldn’t take it. It was way too personal, way too emotional.”

He explains: “I’m a supercompetitive person, and I’ve always been really driven to create my own mark. I loved who my dad was, I loved that he was a great player and coach and all these things, but I was already being referred to as Doug Collins’s kid, and quite frankly, I didn’t like that. My whole goal growing up was that one day, when they write ‘Chris Collins,’ it would not say ‘comma, son of Doug.’ ”

That doesn’t mean he didn’t absorb his father’s wisdom. One venue provided neutral ground: the living room, with a game on satellite TV, dad on one couch, son on the other. Says Collins: “He’d explain to me what’s going on—‘This is why they’re doing this, and here are the adjustments.’ Just X’s and O’s strategy.” Recalls his father: “I might ask, ‘Now, why do you think they did that?’ ”

At Glenbrook North, the local high school, Collins joined a team that was hardly a powerhouse. Or, as he puts it more directly: “It was a graveyard for basketball. People would ask, ‘Why would you go there? They’re no good. You’re going to lose.’ To me, that was the exciting thing about it—the opportunity to change that, to leave a legacy, to be that someone who put Glenbrook basketball on the map. I wanted to leave my own mark.”

Opposing fans didn’t make it easy for him. “When I was playing on the road, I was hearing the chants: ‘Daddy’s boy,’ stuff like that,” he recalls. But he embraced it. “I loved people chanting at me. It really got me thick-skinned early.”

The taunts certainly didn’t hurt his play.

His senior year, the 1991–92 season, the 6-foot-3 Collins put up 32 points a game, shot a ridiculous 47 percent from the 3-point line, and was named Illinois’s Mr. Basketball, an award given to the state’s top high school player. He also led Glenbrook North to a 27–3 record and its first-ever supersectional appearance, one step from going downstate for the state tournament’s quarterfinals. (The team lost the game, played at Northwestern’s Welsh-Ryan Arena, in triple overtime.)

At Glenbrook North, Chris Collins and his teammates created this hype video for the 1991-92 season, set to MC Hammer’s “2 Legit 2 Quit,” that doubles as a time capsule. Come for the highlights, stay for the dance numbers.After Mike Krzyzewski came calling, Collins enrolled at Duke, which his dad describes as “quietly his dream school.” By his sophomore year, he was a key player coming off the bench, averaging 10 points in helping the Blue Devils reach the national championship game, which they lost to Arkansas.

Then, for the first time in his life, Collins faced real adversity. On the first day of practice his junior year, he landed oddly while running a routine fast-break drill. “I felt kind of a crackle,” he recalls. “I went over to the trainer, and I’m like, ‘I sprained my ankle,’ and he said, ‘Then why are you holding your foot?’ ”

Collins had suffered a break that required surgery to implant a screw. He was out eight weeks—missing the rest of the preseason practices and the first three games. When he came back, both he and the team struggled. “I just could never get right,” says Collins, who eventually lost his starting spot. Then, 12 games in, Krzyzewski decided to take a leave to recover from back surgery and exhaustion. Duke went into a nosedive, finishing 13–18 and missing the NCAA tournament for the first time in 12 seasons.

“The bottom just fell out,” Collins says. “I was at a crossroads. I’ve always been very self-confident. I’d lost that. I knew I had to either figure out how to get it back or quit.”

His father could sympathize. His rookie year he’d also broken his foot. “People were saying, ‘Oh, he’s just another 76ers draft pick bust,’ ” Doug recalls. He battled self-doubts, too, but he also developed the philosophy that he now passed on to his son: “If you want to succeed, one, you better be resilient and, two, you better have grit.”

His son took it to heart. That summer, after some soul-searching, he went into “an unbelievable mission mode,” he recalls. “I wanted to get back to the basics of who I was.”

He returned for his senior year no longer the coach’s favorite. “We had all these McDonald’s All-Americans coming in. I think Coach K always valued me, but frankly, coming off the awful year I had, he was a little down on me. I was an afterthought.”

Collins had a different plan. He wound up starting every game, averaged 16 points, and was named second-team all–Atlantic Coast Conference. In his last game, however, he rebroke the foot, damaging his NBA draft prospects.

He played in Finland for a year, then tried to catch on with the NBA’s Minnesota Timberwolves—and very nearly made it. “He reached the final cut,” his father says. “One of the things he realized very quickly was that he didn’t want to be the guy chasing that last spot and maybe not getting it again. He was ready to move on.”

He decided to try his hand at coaching—a notion he’d never given much thought to. “I’d always wanted to be a player,” he says. What got him interested? “My love of basketball. There was nothing in life that gave me the feeling of being in a gym—no desk job. There’s something about the game. It’s a passion. I had to be part of it, and coaching was the next best thing.”

He worked as an assistant for the WNBA’s Detroit Shock for a year, then joined the staff at Seton Hall for two seasons. In 2000, Coach K came calling again, bringing Collins on at Duke. During his 13 years there, the team won two national championships, and he rose to be Krzyzewski’s top assistant. He also began a family with Kim, whom he had met in New York City while he was working at Seton Hall.

Then in 2013, Northwestern, long the doormat of the Big Ten, approached Collins. He had his doubts. “There were a lot of people around me who were saying, ‘You’re nuts for even being interested in this situation. You’re putting your neck on the line. What if it doesn’t work?’ ” The parallels between those warnings and the ones he’d heard entering Glenbrook North didn’t escape him. Nor did the irresistibility of the challenge.

A conversation with Coach K proved the clincher. Recalls Collins: “He just told me, ‘If I was your age, I’d be all over this. I’m telling you, they’ve just been waiting for the right guy.’ That gave me a lot of confidence.”

And so began the Chris Collins era at Northwestern, a school with a trash heap of coaches who had come in with great promise (Bill Carmody, Kevin O’Neill, Bill Foster), only to fall short. Collins’s first move was to bring onto his staff someone he trusted: his old high school coach, Brian James. Since leaving Glenbrook North in 1995, James had worked for a handful of NBA teams as an assistant coach or scout. “To me, it was a no-brainer trying to get him to come with me,” Collins says. “He’s someone who was practically family, but also superqualified and really talented. So you have someone who is part of your inner circle that you know you can trust and is going to be loyal.”

They turned their attention to recruiting, long a struggle for Northwestern. Knowing that most blue-chip prep stars were out of their league, Collins says, they had to “do a good job of evaluating and finding some guys who were maybe a little under the radar, but who could be really good.”

To run his offense, he needed a strong point guard, the same position he had played at Duke. He and James targeted Bryant McIntosh, a converted shooting guard from Indiana who was “really good,” Collins says, “but someone who wasn’t considered a top 50– or 100–type player.”

Recalls McIntosh: “They didn’t just recruit me, they recruited my family: my girlfriend, my godfather, my grandparents.” He remembers Collins’s pitch well: “He said that I could be part of something special, that everybody remembers the first time something is accomplished, and that we could be remembered forever.”

McIntosh committed to Northwestern that September. But even before then, the coach had landed a bigger name, signing Vic Law, a local product out of St. Rita. No. 66 in ESPN’s national rankings, the 6-foot-7 forward was the highest-rated recruit in Northwestern’s history.

But Collins wasn’t done. He also had his eye on another Chicago-area player, Scottie Lindsey, from Oak Park’s Fenwick High School. Lindsey’s stock had dropped after he broke his leg that August in a pickup game during a recruiting trip to Vanderbilt. “There was trepidation because it was pretty serious,” Collins says. “He was in a full-length cast.”

As James remembers it, Lindsey called Collins. “Do you believe in me?” he asked the coach.

“Yes, I do. I believe in you.”

“Will you take me right now even with a broken leg?”

“For sure.”

That was enough for Lindsey, who committed to Northwestern.

The strength of that recruiting class sent a clear message that Collins was serious about turning the program around. But it would be a year before any of those players, 2014 high school grads, would arrive on campus.

In the meantime, Collins had to win over his current players. They were stunned by the canning of Bill Carmody, a man who had recruited them and coached the Wildcats for 13 years, including back-to-back 20-win seasons in 2009–10 and 2010–11. Some even felt responsible after a 13–19 season in 2012–13 led to his ouster.

“We knew his getting fired was a possibility, but we also thought maybe it wouldn’t happen because of the number of injuries,” says Sanjay Lumpkin, then a redshirt freshman guard, who had missed most of that year with a broken wrist. “It was definitely a transition, definitely a time of uncertainty.” Still, with Collins’s pedigree, “there was a buzz around the whole Evanston area when he was hired,” Lumpkin recalls. “We were superexcited.”

As Collins saw it, his most critical mission was to change the culture of Northwestern basketball. He laid out his vision to players at a dinner at an Evanston steakhouse. “He wanted to change the perception of us being lovable losers to a team that expected to win,” Lumpkin says. “A lot of guys bought in, and some guys didn’t. The guys who didn’t, didn’t make it.”

Explains Collins: “I thought coaching was all about strategy—putting guys in, taking them out, all that stuff. But I realized, being around Coach K, that the most important thing is getting the group of guys that you lead to believe in you and want to fight for you. In order to do that, they first of all have to know that you love them, that you care about them, that you have their best interest at heart.”

The team felt a difference on the court, too. “The practices were quicker, more streamlined,” says Pat Baldwin, a former Northwestern player whom Collins brought on as an assistant. And the emphasis, at least initially, was on defense, slowing the game down. “For the first couple of workouts, we didn’t even touch a basketball, which was definitely a change to everyone there,” Lumpkin recalls. “He wanted us to know we were going to be a hard-nosed, blue-collar team. We’re going to stop guys, and the defense was going to win games.”

One former player, Kale Abrahamson, remembers finishing what seemed like a routine scrimmage—only to receive a group text from a teammate later. “Guys, get here early,” it read, according to an account on the website Inside NU. “Film room. I’ve never seen a coaching staff this mad in my whole entire life.”

“We didn’t know what we did,” Abrahamson recalls. “We walk in there, and they played the film of that scrimmage. It was a 15-minute scrimmage and it took three and a half hours. And there was a lot of bad words in that meeting. It was superintense. That woke us up quick.”

Through the first part of the season, the team played solidly but not spectacularly, going 7–6. Then came their first Big Ten game, against No. 4 Wisconsin. “We were all geared up,” Collins recalls. “Then I walked out [into Welsh-Ryan Arena] and 60 percent of the crowd is wearing [Wisconsin] red.”

Things got worse from there. At halftime, the Wildcats found themselves down by 26 points. “I’m sitting in the locker room staring at the wall,” Collins says. “For the first time I really just didn’t have any answers. Really, I was just staring at the wall like, What do I do?”

James was speechless as well: “We didn’t even meet each other’s eyes. It was like, What have we gotten ourselves into? He’s left the best college program in the country, I’ve left the pros, and we’re down 40–14 in our first conference game.” Adds Baldwin: “It was a wake-up call as to how much work had to be done.”

Recounting the story in his Evanston office, Collins points out a framed photo on his wall, a group shot of his five starting players from that first season—the ones who were humiliated at home by Wisconsin. This particular photo, though, was taken under much more joyous circumstances. “One month later, those same guys went up to Wisconsin, and we beat them on their home floor,” Collins says. “It was like, ‘OK, here we go.’ That picture will always be in my office.”

But it certainly wasn’t the last test Collins would face in building the program. After a lackluster 14–19 first season, his team started out the next year a promising 10–4. They then proceeded to lose 10 conference games in a row. “This was the hardest thing I’ve ever dealt with,” says Collins. “Going two months and not winning a game, coming back every day and trying to get these guys in practice without ever tasting the joy of what it feels like to win—that was awful.”

It was enough to shake Collins’s confidence. “I was asking myself questions like, Am I doing the right stuff? Am I saying the right things?”

Searching for answers, he turned to his father, who now worked as an NBA television analyst. Recalls Doug: “He said, ‘Dad, what do you think?’ I said, ‘It’s not about X’s and O’s, Chris. You’ve got to get their spirits built back up.’ ”

Collins’s solution was to do a complete reset. At practice, he started piping in music to loosen up his players. And he all but threw out his old playbook. “We changed everything,” he says. “We had played all man-to-man defense. We went to all zone. We put a bunch of new plays in the offense.”

The team responded, ripping off four straight Big Ten wins. But in that fraught period arose what has been the only real controversy involving Collins. Johnnie Vassar, a freshman point guard at the time, would later accuse Collins of berating him in front of teammates after one of those losses and then pressuring him to transfer. Vassar eventually did leave the team. A year later, he made those allegations in a lawsuit against Northwestern and the NCAA that challenges NCAA rules requiring transferring players to sit out a year. The suit is winding its way through court. Northwestern issued a statement saying Vassar’s allegations “are without merit and simply inaccurate.”

Despite having found their footing again, the Wildcats finished the 2014–15 season a middling 15–17, but the momentum seemed to carry over into the next year, Collins’s third, when the team finished 20–12.

Even with the steady improvement, an invitation to the NCAA tournament still eluded the Wildcats. But as the 2016–17 season rolled along, the anticipation that this might be the year began building. By the end of January, the team was a stunning 18–4, having won six straight Big Ten games, and that initial class of recruits Collins had landed—McIntosh, Law, and Lindsey—was leading the way.

“Everywhere I went,” says Doug Collins, “when I broadcast a game, every NBA coach I came across, walking through airports, walking in Starbucks with my Northwestern gear on, people would say, ‘We’re so cheering for you guys! We’re cheering for Chris. I can’t believe the job he’s doing.’ ”

The team stumbled, though, winning just two of their next seven games. The last of those was a heartbreaking loss to Indiana in which the Wildcats had been up by 7 with a minute and a half left to play. Says Collins: “I remember going into the locker room [after the game] like, How do I keep these guys from losing hope?”

Until then, Collins had avoided addressing with the team its prospects for making the tournament. But he figured the mounting pressure was getting to them anyway, and at 20–9, Northwestern no longer seemed like a shoo-in. “I feel like that was a key moment in all of this,” he says. “Something in my gut told me that we needed to stop skirting the issue. I realized that even though I’m not talking about it, it’s all the players’ families are talking about. It’s all they’re seeing on social media. So me not talking about it, it was almost like I was being naive.”

Next up was a tough home game against Michigan, and two days beforehand, Collins bluntly laid things out for his team. “If you want to go to the NCAA tournament, we have to win,” he told them. “And if that’s too much pressure, then tough.” Facing the situation head-on was actually a relief for the players, says Lumpkin, adding, “We stepped up to the challenge.”

It wouldn’t come easy. With the seconds ticking down and the score tied, Michigan’s Zak Irvin launched a 3-pointer. He missed, and the ball was knocked out of bounds in a scramble for the rebound. Possession was awarded to the Wildcats, with 1.7 seconds left.

In the Northwestern huddle, James cautioned Collins about taking any big chances. The Wildcats were taking the ball out under their own basket, a full court length from where they needed to score. Recalls Collins: “He was in my ear, saying, ‘A lot can go wrong. Let’s just get it in [bounds]. Let’s not do something stupid. Let’s go to overtime.’ ”

No, Collins said. “We gotta go for it. I want to try to win, and I want you to draw up a home-run play to get it done.”

Both he and James knew who would throw the ball in: 6-foot-7 senior Nate Taphorn. “Throughout the course of the season, you always do drills with baseball passes so if you’re in that situation, you want to see who you want,” Collins says. “He was always the best at throwing long and being accurate.”

But early in the year, during a key inbounds late in a game against Notre Dame, Taphorn had thrown the ball away, and Northwestern wound up losing. “The whole year he had lived with the regret of that, feeling like he blew the Notre Dame game,” says Collins.

The stakes were even higher now. Throw the ball out of bounds and Michigan would get possession near the basket—with enough time to win the game. Recalls Collins: “The only thing I said [to Taphorn]—and I must have said it 10 times—is, ‘Don’t overthrow it, don’t overthrow it.’ ”

The ref, whistle in mouth, handed Taphorn the ball. As instructed, Taphorn looked for 6-foot-8 center Dererk Pardon down near the basket, some 90 feet away, and let loose a pass like an NFL quarterback. The ball sailed in a long, graceful arc just to the right of the hoop.

Pardon caught the ball with two hands, over his left shoulder,

then went up and dropped it off the backboard and in.

Bedlam.

Fans swept onto the court. Pardon’s delirious teammates chased him to the sidelines, mobbed him, burying him in a sweaty, euphoric pile. Collins, in a dark suit, his tie flapping, mouth agape, took a big skip, then leaped into the air. As the bench emptied behind him, he grabbed a player, then looked around for someone, anyone, to hug. Moments later, he saw a blond woman wearing a wide grin sprinting down from the stands. “Chris!” Kim yelled before wrapping her husband in a bear hug.

Northwestern’s fantastic finish against MichiganFor good measure, the Wildcats won two more of their last four games, including making it to the semifinals of the Big Ten tournament, to all but ensure themselves—at long last—the prize that had eluded them for the better part of a century: an NCAA tournament bid.

On Selection Sunday, when the 68 teams in the tournament field were announced, Northwestern fans, players, and coaches gathered in Welsh-Ryan Arena, eyes glued to overhead TV screens, waiting to hear the Wildcats called for the first time ever. And waiting. They weren’t in the East, the first region unveiled. Or the Midwest. Or the South. They had to wait until the last of the four brackets, the West, was announced (“Of course,” Collins laughs), but there it was: Northwestern the region’s eighth seed, facing ninth-seeded Vanderbilt. Collins, McIntosh on his left, Lumpkin on his right, the rest of his players filling out the bench on either side of him, reprised his Michigan celebration, jumping into the air, both arms raised, index finger pointing skyward on each hand, as his players jumped and shouted around him.

Shortly afterward, ESPN did a live interview with Collins, and the network had a surprise for him, bringing up his dad, who was offsite for an NBA game he was calling, on a split screen. “Congratulations, buddy,” Doug said. “I know all that you’ve put into it, and … to see this happen today was incredibly special for me.” The coach soaked it in. “It was great to hear his voice,” he told the ESPN studio panel, his tone thickening. “He’s been my hero in the game, obviously a mentor, but the best thing he is to me is a dad.”

Now it was time to get to work. Northwestern had a game to play. Collins’s message to his team: “They call it the Big Dance. When you go to a dance, do you just show up and listen to one song and leave? Let’s dance for a few songs.”

Playing 1,400 miles from Evanston, in Salt Lake City, but with the crowd clearly behind them, Northwestern built a 15-point lead in the second half against Vanderbilt, only to see it evaporate in the final minutes. But then, with 14.6 seconds left and his team down 66–65, McIntosh, who had 25 points in the game, sank two free throws to put the Wildcats back up for good.

Collins was particularly proud of the victory because it affirmed that his team belonged in the tournament. “It was a great opportunity for us, as a program, to show where we were at.”

The next game presented an even bigger opportunity—and challenge: The Wildcats faced Gonzaga, the region’s top seed and a perennial Pacific Northwest powerhouse. A deeply shaky first half, in which the Wildcats found themselves down by as many as 22 points, cast some doubt on whether the team was really ready for the big time.

“We were just a little jittery,” Collins says. “I remember going into halftime and saying to the guys, ‘Look, I don’t know if we’re going to win, but we weren’t ourselves this half. We’ve had too good a year. We’ve been too determined. We’re too tough of a team to come out here and just roll over. Let’s start fighting and just see what happens.’ ”

They did. And after a run of 3-pointers, Northwestern had Gonzaga on the ropes, pulling to within 5 with five minutes to play. Then came the most infamous noncall in Northwestern’s history. Pardon put up a point-blank shot at the rim that a Gonzaga player blocked by reaching up through the basket—a clear goaltending violation that the refs missed.

Collins blew up, drawing a technical foul that ended the Wildcats’ run, effectively sealing the win for Gonzaga and striking midnight on Northwestern’s magical season. Cue the kid-bawling-in-the-stands meme.

“I should have just been calm and not let it rattle me,” says Collins. “But in that moment, you’re in a fight. You’re in a battle. You see something and you’re going to instinctively have some sort of reaction.” He continues: “I’m not going to say we would have won the game, but I would have loved to see what would have happened that last four minutes. We were playing really confidently.”

The meeting in Collins’s office has broken up. The coach pulls a tissue from a box after sneezing again.

The pressure is on this season. Northwestern boosters ponied up big to help fund a $110 million massive overhaul of Welsh-Ryan. University officials have promised a state-of-the-art arena, with chair-back seats in place of wooden bleachers, increased capacity, premium seating areas, new concession stands, more bathrooms, and five elevators replacing the lone existing lift. In short, the kind of facility that befits an elite program. But the renovations will put the venue out of commission all season; the Wildcats will play their home games at Allstate Arena in Rosemont.

If he needs any inspiration for an encore, Collins only has to look to his old mentor, Coach K, now in his 38th season at Duke. “Any time I find myself feeling a little satisfied, I think of him,” Collins says. “He’s won five national championships, a thousand games, three Olympic gold medals, and he still coaches as if he’s accomplished nothing. He still has a drive as if he’s chasing his first win. That has always stuck with me.”

Which is a good thing, because expectations are high for Northwestern. The team is returning with its top five scorers and all but one of its starters: Sanjay Lumpkin graduated and is now playing professionally in Belgium. Also gone: assistant coach Pat Baldwin, lured away by the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee to head the program there. Success comes with a price.

One person unlikely to leave anytime soon, though, is Collins. In April, he signed a reported eight-year extension at $3 million a season, dispelling worries among the fan base that another school might try to entice him.

Also dispelled, in his first meeting with this year’s squad, was any notion that Collins is satisfied with last year’s historic run. Sweeping the faces of his players, old and new, with an intense glare, he laid out a new set of expectations at the mid-September meeting. “We won last year because we willed it,” he said, the moment captured by an in-house video crew. “You guys were not going to be denied and you put in the work and you were the most together team in the conference. If you lose those elements, we will lose.”

The magic of last season, like his cold, is fleeting. “Come tomorrow,” Collins told his team, “there’s one mission, it’s the championship mission. That’s the only goal I have. I want to be a champion.”