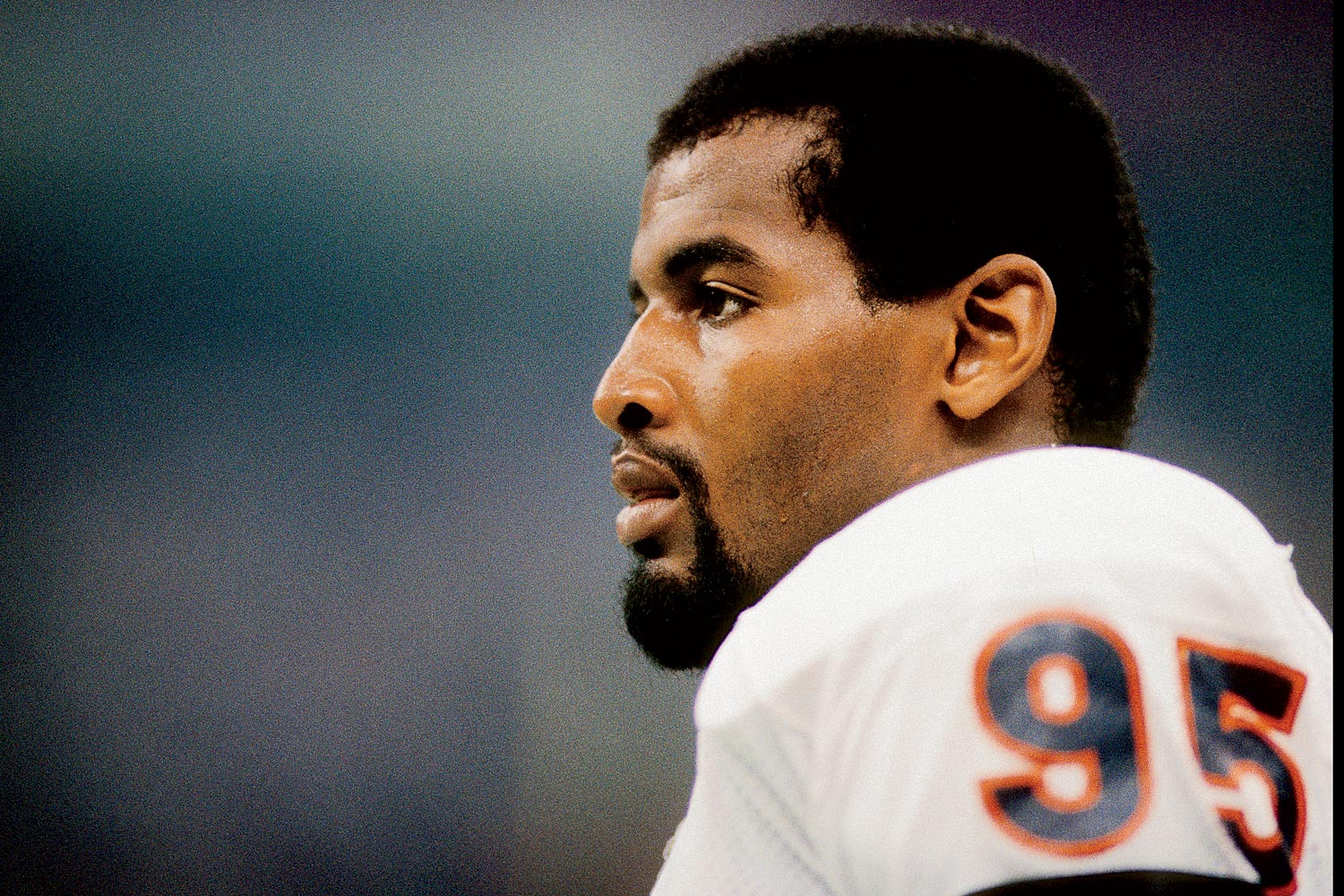

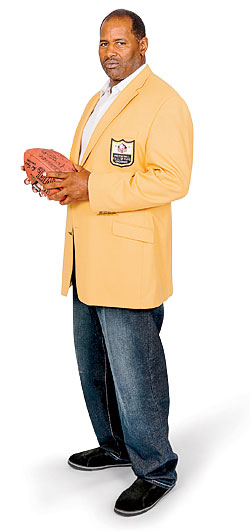

He was, simply put, the most fearsome player on the most iconic team in Chicago sports history. As a Pro Bowl defensive end for the 1985 Bears, Richard Dent thrilled fans and obliterated quarterbacks. Over the course of his 15-year career (12 with the Bears), he racked up 137.5 sacks, which ties him for seventh most of all time. In 2011, he was elected to the Hall of Fame.

What many fans don’t know, though, is that Dent’s playing days left him with a slew of debilitating conditions (specifically, an enlarged heart from prolonged use of painkillers and nerve damage in his right foot from a separated toe). In a lawsuit filed against the NFL in May, the soft-spoken Georgia native, along with seven former players (including teammates Keith Van Horne and Jim McMahon), alleges that teams supplied players with painkillers without providing prescriptions or warning them of possible downsides and in some cases hid from players the extent of their injuries. In addition to seeking punitive damages, the suit demands that the league create a pain medication monitoring program. Both the Bears and the NFL declined to comment for this story, citing pending legislation.

Dent, 53, now owner and CEO of a Chicago-based energy and telecommunications company, recently sat down with Chicago contributing writer Joel Reese.

Why take on the NFL?

When you come into the league, you expect that your team will look out for you, do what’s best for you. You’re given pills and painkillers, but when it’s over, you don’t see any record of that. When I filed for disability and looked at my medical file, how many pills I’d taken, how many shots—none of that was in there. “Oh, you separated your toe. What did you take?” That’s where the problem lies. I have two boys, six and nine. I don’t want to look at them later in life and say, “I had a chance to do something about it and didn’t.”

What do you want this suit to accomplish?

Changing the policies within the game. For instance, I took two physicals every year I was in the league. That’s 30 physicals. Yet no one ever pushed any paper in front of me telling me the outcome, how my body was looking. That affects me now. My rookie year, I had a major tear in my hamstring. Four guys fell on me in the first preseason game, and I did the splits. I was given Tylenol and codeine, but those type of things just didn’t work for me. So I was started on something else. One of the pills might have been Percodan [a prescription painkiller]. When I took that, I felt like I could do anything. But there was no accountability of letting a person know, “Hey, look, Richard, we’ve given you 50 Percodan. That’s your limit—you can’t take any more.”

So you didn’t know what you were taking?

No, I’m not a doctor. I assumed they knew better than me. When I first came to the league, a lot of these pills were just sitting in a bowl on the table. [The suit claims that jars of amphetamines were routinely left in the Bears’ locker room for players to take.] But I didn’t really know what they were. It’s all about getting you ready to play. Whatever we need to do to play is what is important. After my career was over, I was like, “Why is my body acting like this?” I didn’t know that I had an addiction to pain meds. It took me five or six years to really understand what was taking place. I had no source for the kind of meds they had been giving me, but I would dip into the Tylenol or Advil or Aleve—four or five or six a day.

Were a lot of Bears taking excessive painkillers?

I saw a lot of that, every day. It was normal. On the plane, off the plane, in locker rooms, wherever. The little brown envelope—that’s what’s in there. Pills.

On the plane?

After away games, they’re walking up and down the aisle passing out beer, wine, and meds.

Isn’t some of this just the nature of the game?

I understand this is a violent game. It’s not a contact game. It’s a collision game. I understood that I could get paralyzed, anything could happen to me while I’m out there. But the league’s duty is to make sure that they’re looking out for my well-being. I didn’t know I was out there fighting by myself, all alone. There was a situation one time in 1990: I intercepted a ball, the guy tackles me, and my toe pops out. It’s separated. You could go get surgery, but then you’re gonna be gone for the whole year. [The team doctors] say, “Or we could numb it up and tape it down [and you play on it], because most of the damage has already been done.” They weren’t thinking long term. They were thinking short term.

Does the league have a responsibility to players after they retire?

I’m getting paid for my time [while I’m playing], but after I leave, I’m a worn-down horse, and you know, I think I deserve something for that, to keep me living. I’ve been taking all this stuff, but now I can’t sleep, I can’t breathe. I stop breathing five or six times a night, maybe for 30 or 40 seconds. You have guys dying in this industry, and they’re in their 40s and 50s, and nobody’s doing anything. The thing about the NFL is, the owners have all the rights. This is closer to slavery than anything.

What if your sons wanted to play football? Would you be opposed to that?

No, I wouldn’t. I look at it this way: It’s your life. I brought you into the world, and I can show you the world, but you choose what you want to do. But we don’t have to go there now—I didn’t play football until high school. Music is a big part of their lives. One plays the harp, one plays piano.