Growing up in Chicago in the 1950s and ’60s, Margo Jefferson enjoyed all the luxuries of an upper-middle-class childhood. Her father was a pediatrician, and her mother, a University of Chicago graduate, was a socialite. The family lived in tony parts of Bronzeville and Park Manor and, eventually, Hyde Park, where Margo and her older sister, Denise, both attended the prestigious University of Chicago Laboratory Schools.

They were well-off—“comfortable,” as Margo’s mother would say. They were also black.

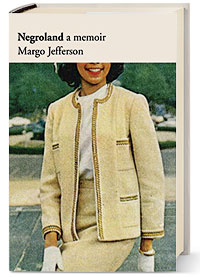

In her new memoir and social history Negroland (out September 8), Jefferson, a Pulitzer Prize–winning former New York Times art critic who now teaches at Columbia University, examines the cultural mores of this select social class, rarely written about with such thoughtfulness: “Inside the race we were the self-designated aristocrats, educated, affluent, accomplished; to Caucasians we were oddities, underdogs, and interlopers.”

Negroland, which takes its title from Jefferson’s term for the black elite of the time, is rife with examples of this stinging, subtle racism: A police officer stops her father on his way home and asks if he’s selling drugs in his own neighborhood. Two white classmates ask her if she is friends with the school’s black janitor. A white acquaintance rescinds an invitation to a dance because “my mother would commit suicide if I did.”

“We were a class within a caste,” explains Jefferson, 67, calling from New York, where she’s lived since 1969. Jefferson may have attended a predominantly white school, but by and large her neighbors and friends were black. (The Jeffersons lived down the street from the Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens and were friends with John and Eunice Johnson of Johnson Publishing, the company behind Ebony and Jet). Navigating those two worlds required a certain dexterity. “We had to constantly negotiate social interactions,” says Jefferson. “Were you around blacks who might be resentful of your wealth, or were you around whites who made it clear you were inferior?”

Negroland is not a conventional memoir. Jefferson writes in vignettes, sometimes in the third person, sometimes in the first. She juxtaposes childhood memories with historical biography (of the civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune, for example), musings (on, say, Lena Horne’s face), and close readings (of James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, among them). The history lessons can be a bit monotonous, and her prose overwrought. (One chapter begins: “All the bright young faces, generations of them, learning the standard race curriculum of wounds and grievances!”)

But at its strongest, the book delivers thoughtful ruminations on what it means to be black and economically privileged and on the tensions that inevitably arise as a result. About the arrival of the Black Power movement in the ’70s, Jefferson writes, “We’d let ourselves becomes tools of oppression in the black community. We’d settled for a dessicated white facsimile and abandoned a vital black culture.”

Thanks in part to the high profile of a certain Kenwood family who now lives in Washington, D.C., Chicago’s black bourgeoisie no longer suffers from a lack of exposure. Jefferson acknowledges as much. For her, Negroland is both a personal look back at her childhood and an examination of this social group. “Who you are in the world and how you look at your history and respect its beauties and criticize its flaws,” she says, “that has a lot to do with why I wrote this book.”