As a kid on Long Island, Jesse Ball thought he would grow up to become a caretaker for his older brother Abram, who was born with Down syndrome. “I even worried (as a boy) about finding a partner willing to live with my brother and me,” he writes in the preface to his new novel, Census, out this week. But after more than a dozen surgeries, Abram died in 1998 at the age of 24.

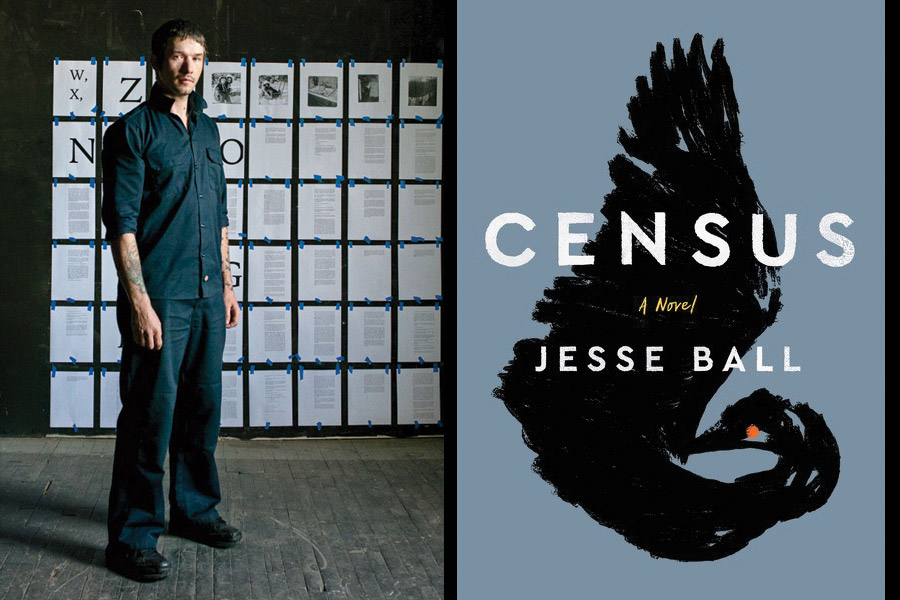

In the years since, Jesse Ball has become one of the most iconic writers in America, a knife-sharp surrealist in the vein of Italo Calvino. He moved to Chicago in 2007, when he took a teaching gig at the School of the Art Institute, and now lives in Lincoln Park. A few months after finishing his last novel, How to Set a Fire and Why, he decided to write a book about his late brother.

The result is a brutal but beautiful story of a dying widower and his son on a road trip across an unnamed country. After learning he only has a few weeks to live, the father becomes a census taker, traveling through 26 cities named after letters of the alphabet, going into people’s homes and marking them with a ribcage tattoo at the behest of a shadowy government.

Like Abram Ball, the widower’s son was born with Down syndrome, and their relationship mirrors the one Jesse imagined with his brother as a child. “But it is not so easy to write a book about someone you know, much less someone long dead,” Ball writes. “I didn’t see exactly how it could be done, until I realized I would make a book that was hollow. I would place [my brother] in the middle of it, and write around him for the most part.” To that end, the widower’s son is always present, but never fully seen or heard.

I recently spoke with Ball over the phone about writing that hollow book, as well as Chicago, American morality, and of course, death.

Where in Chicago do you usually write?

Most of the time, I don't write. But there are breaches in the edifice of my regular life where I'll go and write a book, usually in about a week. I pick a cafe and I work in that cafe. Lovely in Wicker Park was the first one. I wrote my last two books—How to Set a Fire and Why and Census—at a place called Ch’ava on Clark, near the cemetery. I loved that place. It went out of business.

Where is Census set? At times it feels a lot like the post-industrial Midwest.

It's really set in the present—in any first-world, modernized place. The setting is just kind of sketched in, because I’m not a proponent of this realistic view of fiction. If your character walks into a Taco Bell, what the reader can feel about someone being in a Taco Bell is already constrained in a way. There are people who make it their specialty to de-familiarize these places, to fight a war of words. That's just not my personal ambition. I don't have the stamina to cite Coca-Cola and Crest toothpaste and Shell gasoline.

How did the concept of the census enter the story?

I didn't know it was going to be in the story, but when it appeared there on the first page, it seemed like the shape and scale of that metaphor fit the kind of interrogation I was adapting. The census was an excellent vehicle for articulating the different ways we see the world—the way a conformed, consensus person sees it, the way a person with Down syndrome sees it, this concatenation of all possible visions, and the distinction between objects.

In the preface, you describe writing the novel “around” your brother, who would be like a “hollow” space at its center. Why did you take that approach as opposed to something more direct?

For me, it wasn’t possible to write about him directly because the English language is the aggregate speech of all English speakers historically, especially English speakers with power. And historically, that language has not been kind to people with mental disabilities. The language inherently forces a kind of a pantomime caricature, like a “donkey laugh, or whenever people say “d-d-d-d-d-duh,” or “retarded.” I wasn't going to permit him to be written about in a way that didn't have dignity—not like the dignity of the Queen of England, but the basic dignity that human beings have and should have. So it had to be written in the negative.

What do you think most people misunderstand about Down syndrome?

They don’t know much because they essentially choose not to. When there's a person with Down syndrome in public, people will avoid looking at them. I can't say exactly what people think, but they should attempt to see the reality.

I think one of the questions America has ceased struggling with is what it means to be moral. On the one hand, there's this cartoon morality. On the other hand, you have people who say morality is so complicated that anything is fine, some sort of pandering nihilism. In this book, and in all my books, I try to say that morality is not so complicated. It's very simple — you can try to be gentle and generous and kind. But if you're in this brutal, possessive, American mode of morality, you can't even see who's standing in front of you, because everything’s mine, mine, mine. You're my enemy or you’re my friend. Everything is in this bifurcated distribution of horror and shit.

One of the blurbs on the back cover of Census says your view of the world “might be described as tender nihilism…”

I think it’s nihilism because the United States is a theocracy. I'm an atheist—I believe you die and that's it. I don’t believe in a magical energy that flies around and flows from this person to that person. Things mean exactly what they mean. I don't believe in a grand ethical power that predates humanity. I think the most pathetic thing about human beings is anthropocentrism. The way we treat animals is one of the worst things in the history of existence. So if you add that all together, it ends up seeming like nihilism. But really it’s just looking at what can be proven. I try to be an empiricist.

There are a lot of cormorants in this book, including on the cover, usually as reminder of death. What drew you to cormorants?

The cormorant is a dear friend to me. I’ve always liked them a lot, but I don’t know very much about them. They’ve always fascinated me, so it seemed a fitting thing for someone to be obsessed with, their motion between different planes of being. Even when you see one, they’re so strange-looking, but they're common enough for people to know.

Do you think about death a lot?

I think it's crucial to think about death as often as possible. Maybe there are other ways to properly value your life moment-to-moment, but I haven’t found them.