From my own personal anecdata—I don't know how else you'd measure this—people seem to like the White Sox this year. (Their attendance is pretty bad, but it's only down about 1,000 from 2016 and 2015, and about the same as 2014.)

This is a non-trivial achievement given that they could still finish the season as the worst team in baseball. But after years of unsuccessfully chasing the playoffs with aging, second-tier free agents, resulting in a series of meaninglessly OK teams, they've blown up the whole thing and restocked their farm system while putting a compelling-if-bad team on the field. Yoan Moancada and Lucas Giolito have shown flashes of what made them the team's big acquisitions; Yolmer Sanchez and Nicky Delmonico have exceeded expectations; Avisail Garcia and Jose Abreu have been among the best hitters in baseball.

My favorite White Sox player this year has been Omar Narvaez, their 25-year-old, 5-foot-11, 215-pound catcher. There are better catchers; per Fangraphs' WAR (though it's a cumulative stat), he's only been the 21st-best catcher in baseball. He's probably not a good framer. On a good team he might fulfill his scouting destiny as a "low-end backup or an up-and-down catcher."

But he's gotten the most at-bats of any catcher on this bad White Sox team, and he's been… fascinating. Not great—he's almost literally average—but unique.

His reputation as a prospect was that his sole offensive skills were plate discipline and the ability to make contact. In 88 games, he's shown elite plate discipline and elite contact skills—and basically no other offensive skills at all. Average them out and you get an average hitter.

But the way Narvaez averages them out, if you are into that sort of thing, is wonderful.

Let's start with the basics. Narvaez is hitting .277 with a .375 on-base percentage and a .341 slugging percentage (slugging measures total bases per at-bat, so home-run hitters—sluggers—have high slugging percentages). His batting average is pretty good. His on-base percentage is very good, 36th out of 311 players with 250 or more plate appearances. His slugging percentage is bad, 20th-worst. (Over 408 plate appearances in two years, his slash line is .274/.368/.340, so he's sustained it over a decent sample.)

First, it's unusual for a player to have a slugging percentage that's lower than his on-base percentage. Only eight players out of those 311 have an SLG lower than their OBP. Narvaez has the second-highest negative difference.

From that we know he's an outlier, especially in an era with lots of power and lots of strikeouts. We also know that he's a good contact hitter with an excellent eye and no power. And the way he gets there is wonderfully odd.

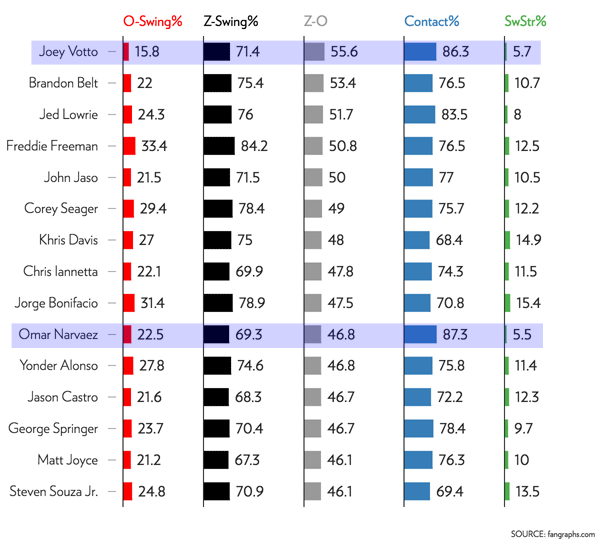

Take this chart. I took the frequency that players swing at pitches in the strike zone (Z-Swing) and subtracted the frequency that players swing at pitches outside the zone (O-Swing) to get a sense of how good his batting eye is. There are different ways of thinking about how selective a player is, but "swings at strikes and doesn't swing at balls" is a pretty good one. And Narvaez ranks pretty high by that measure (Z-O) this year.

He's 10th in baseball among players with at least 250 plate appearances, which is impressive. But I included the other numbers for a reason. Of the top 20 players by this measure, only four have a swinging-strike rate (SwStr%) under ten percent, and Narvaez has the lowest. Only three have a contact rate (how often they make contact when they do swing) over 80 percent, and Narvaez has the highest.

And he's neck-and-neck on contact rate and swinging-strike rate with one guy in this list: Joey Votto, one of the great hitters, from a technical perspective, of all time. This is kind of an arbitrary way of looking at Narvaez—he is not, in the parlance, a "Vottoesque" hitter—but he has a satisfying combination of selectivity and ability to make contact.

Another thing about Narvaez is that he has zero power; he's essentially a singles hitter. According to Statcast, out of 286 players with at least 190 batted balls, Narvaez has the second-lowest average exit velocity, down with speedy slap hitters like Dee Gordon, Billy Hamilton, and Ben Revere.

And he's slow, as his physique suggests. By Statcast's sprint-speed leaderboard, Narvaez ranks 412th out of 451 players, down with the catchers, big power hitters, and old guys. This should be a recipe for disaster, but Narvaez makes it work. Here's a list of the 15 players with the lowest batting power in baseball, as measured by ISO. (Spd is "speed," a "slightly outdated statistic that attempts to measure a player’s running ability." Narvaez has the third-lowest Spd figure in baseball this year.)

Narvaez is a speedy slap hitter without the speed, but he maintains a high batting average on balls in play (.295 last year). And because a wRC+ of 100 means league-average, he's been a decent hitter despite those considerable deficiencies, especially compared to other hitters with his lack of power.

One last thing about the wonders of Omar Narvaez. In 2017 he's pulled the ball 34.1 percent of the time, he's hit the ball to the center of the field 33.2 percent of the time, and hit the ball to the opposite field 32.7 percent of the time. It's a very even distribution–he hits to all fields.

If my use of standard deviation is correct, and it's at least in the ballpark, Narvaez ranks fourth in baseball this year in terms of pure spray hitters. This is neither good nor bad; there are good hitters who hit to all fields, like seventh-ranking Eric Hosmer, and good hitters who pull the ball more than half the time, like 311th-ranking Gary Sanchez (the best-hitting catcher in baseball this year). It's just another aesthetically satisfying way in which Narvaez is an outlier.

Omar Narvaez is a hitting machine. He's not a good hitting machine, relative to his major-league peers, but he's a machine that does a certain number of things beautifully—seeing the ball, making contact, hitting to all fields—and certain other things not at all. The sum total of all this is an almost perfectly league-average hitter and an OK starting catcher, but the joy of it is that, looking behind the sum total, he's anything but average.