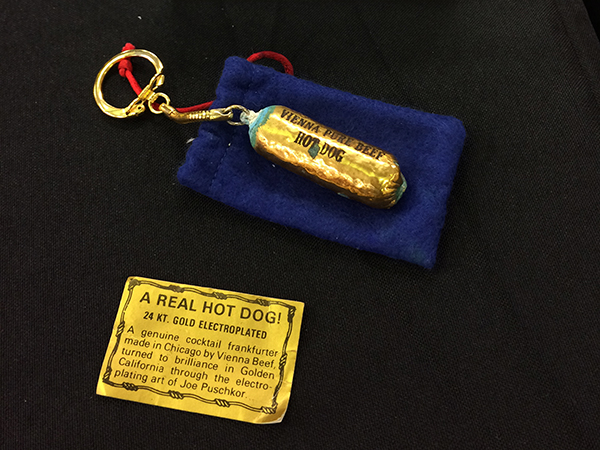

In the 1970s, someone at Vienna Beef came up with a one-of-a-kind idea to promote the company’s sausages: electroplate them in 24-karat gold, and turn the results into keychains to hand out to customers. Cocktail franks were sent to California, where a specialist encased each in a thin coat of metal. It’s the least appetizing way Chicago’s leading hot dog supplier has ever dressed up a sausage in its many decades of being in the business.

This year, Vienna Beef turns 125. To celebrate its long history of hawking hot dogs—most famously, Chicago-style hot dogs—it recently opened a free museum at its Chicago headquarters on 2501 N. Damen Avenue. Occupying a former plant room, the small exhibition features archival documents and an array of paraphernalia that chronicle the company’s origins and evolution—including one surviving gold-plated sausage keychain, whose tips have gone green from corrosion.

“That came out of somebody’s drawer,” says Tom McGlade, Vienna Beef’s vice president of marketing/eCommerce. “I’m sure it’s turned into a rock by now.”

The Vienna Beef History Museum. Photo: COurtesy of Vienna beef

McGlade, working with the company’s chairman and president, came up with the idea to create the Vienna Beef History Museum as one way to engage customers in the quasquicentennial celebrations. He also served as its curator, foraging for objects that, for the most part, have never before been on public display. Much of the material on view was in company offices, while other objects came from the Vienna Beef factory, which occupied the building between 1972 and 2016. Visitors can check out a retired sausage stuffer from 1859, hand-painted signs by Gus Korn, and a whole row of merchandise that underscores the hot dog’s prominent role in local sports culture.

“The rich history of Vienna Beef and how it’s been part of the fabric of Chicago—that’s the number one thing that people can walk away with,” McGlade says. “There are also curious artifacts that demonstrate the evolution of the Chicago-style hot dog from its very beginning at the World’s Fair to today.”

The 1893 Columbian Exhibition featured a number of sausage vendors from Germany and Austria-Hungary jostling for attention. Among them were Vienna Beef’s founders, Samuel Ladany and Emil Reichel, brothers-in-law who had arrived in Chicago three years before. Trained in sausage-making in the Austrian capitol, they set up a stand to sell their chops at a prime location near one of the fair’s entrances. Sales were so strong they ended up purchasing a storefront on South Halsted Street the following year. The pair was Jewish and used beef in their products—hence, the company’s name.

A cocktail sausage, gold-plated in the 1970s. Photo: Claire Voon

Black-and-white photographs at the museum document how one store grew into a booming empire. Ladany and Reichel began supplying sausages to other retailers and food stands, with horse-drawn carriages initially delivering the goods. This fleet became motorized in 1928, and business, of course, got bigger. In later decades, the company’s vice president of sales, Henry Davis, worked with hundreds of hot dog stand owners, helping them to launch their businesses; in return, they stocked Vienna Beef sausages. A portrait of Davis identifies him as “Father of the Modern Hot Dog Stand.”

By 1962, Vienna Beef products were appearing in supermarkets. One decade later, to keep up with the high demand, the company moved into a new factory on Damen Avenue. It knocked down the original plant in style, commissioning a wrecking ball shaped like a giant sausage to do the job.

Today, more than 90 percent of Chicago hot dog stands serve Vienna Beef sausages, McGlade says. While Ladany and Reichel can’t be credited with creating the Chicago-style hot dog—which was born from the recipes of 20th-century immigrants—their wiener has become the quintessential heart of it. A lot has changed since the men opened their store, but their sausage is still made the same way 125 years later.

Of course, a visit to the Vienna Beef History Museum wouldn't be complete without a gustatory experience. The building has a longstanding eatery that now doubles as the perfect museum gift shop. Once you've had your fill of culinary history, be certain to nourish your stomach as well.