On a Thursday afternoon late last September, the Chicago Cubs played the Houston Astros in a back-and-forth slugfest at Wrigley Field. In the eighth inning with the score tied 7-7, the Cubs laboring relief pitcher, Randy Myers, faced a Houston batter with a man on base. Sitting in the stands was a 27-year-old bond trader named John P. Murray, a young man who describes himself as a “huge” Cubs fan ever since he was a little kid going to the ballpark with his family. Watching Myers struggle—and anticipating the demise of the Cubs' threadbare hopes of getting into the postseason playoffs—Murray began to boil over. "Sometimes you get so frustrated," he says. ''You pay so much and the team doesn't get better." Finally, he told his companions that if Myers gave up a homer, he was going to run out on the field and tell the pitcher off. "They said, 'No, you won't.' [I said,] 'If he gives it up, I'm going.'"

Sure enough, Myers's next pitch was crushed for a home run. So Murray trotted down the aisle, hopped the first-base wall, ran past first baseman Mark Grace, and chugged out to Myers. "What the hell was that?" he yelled when he got close to the pitcher.

Myers reasonably feared for his safety—"I felt the look in his eyes, that he wanted to hurt me," Myers said later—and decked Murray with a muscled forearm. After a brief melee, the fan was led away and arrested.

John P. Murray's behavior has been appropriately deplored on all sides. Today, he himself acknowledges it was a "stupid thing" to do. At a minimum, the incident is an argument for better security at sporting events; at worst, it's another dismaying sign of the decline of public life in this country.

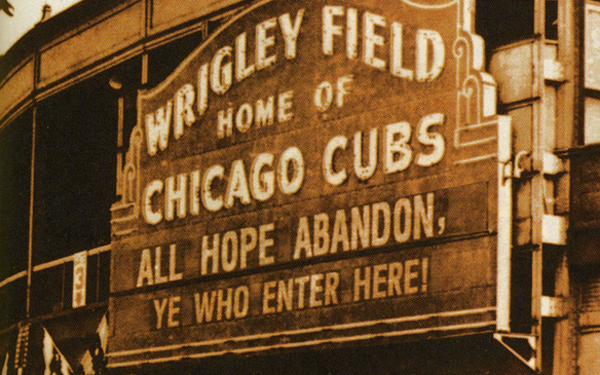

And yet, what true Cubs fan—and by that I'm basically talking about the hereditary variety, bearing the defective gene, usually passed through the father—what true Cubs fan hasn't countless times felt the exact same impulse? The team's phenomenal failure to win mocks the odds and defies the normal cyclical course of human events. Think of the emotional costs. My father, for example, was born in 1917. He lived a life that was long, rich, and productive (despite the habit of turning first thing to the sports pages in the morning paper). He tasted success and he nuzzled grandchildren, and he died without ever seeing his team win a World Series. I’m pushing 50, and I’ve never seen them win a pennant. (For the record, they last won the Series in 1908 and last played in it in 1945.) This is the sort of lush environment to breed a John P. Murray.

These days, under the ownership of the Tribune Company, the club has a fresh management group led by team president Andy MacPhail, who is widely considered one of the best baseball men in the country. “The word around the league is that they are really on the right road,” says the agent Steve Zucker. MacPhail “knows how to win,” says Allan Simpson, the editor of Baseball America magazine.

But MacPhail is swimming against a tradition that has swamped great baseball talents before him, from Bill Veeck to Leo Durocher to Dallas Green. Why? Why this miserable history? We’ve all heard the silly explanations, the stories about black cats, billy goats, and hexes, the kind of nonsense that perpetuates the tedious notion of the Cubs as lovable losers. But there must be more do it than that, some rational answer grounded in science or history or business. To try to find out, I’ve talked to baseball experts, team executives, statisticians, reporters, agents, players, managers, fans—even some sports psychologists. In short, I’ve made an obsessive, even paranoid journey to the heart of Cub darkness, and back again.

The news, friends, is not good.

A BIT OF CONTEXT

Americans are so fixed on winning that we celebrate the great successes in sports—DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak, the Bulls' threepeat, Vince Lombardi's indomitable Packers—without, perhaps, devoting sufficient awe to monumental feats of failure. In that pantheon, the Cubs are true giants. Remember, this is a professional team whose business is baseball. Let’s start with winning a league pennant, the ticket to the World Series. Early baseball history is a muddle of teams and leagues, but once the Series was started in 1903, the old St. Louis Browns (later the Baltimore Orioles) went 41 years before getting there, in 1944; that record was later matched by the Athletics (from 1931, when they were in Philadelphia, to 1972 in Oakland). The Cleveland Indians, who made it last year for the first time since 1954, also went 41 years between Series berths. But none of those low achievers measure up to the Cubs, who are at 50 years and counting. As for actually winning a World Series, no major-league club approaches the Cubs' record of futility: an eighty-seven year drought—fourscore and seven years. (Miserably enough for Chicago, the closest rivals for Series frustration are the White Sox, who reigned champions 78 years ago, in 1917.) When the Cubs last savored triumph, Henry Ford was introducing his Model T. Geronimo was still alive. The Drake Hotel wouldn't go up for another decade.

Even more disheartening, I haven't turned up another team in a major professional sport with a record of failure approaching the Cubs'. In football, the peripatetic club called the Cardinals hasn't won the big one in 48 seasons. In hockey, the New York Rangers went 54 years without a championship, then won one, two years ago. The National Basketball Association has been around only since 1949, and the Phoenix Suns—formed in 1968—are the oldest winless club.

Though this would seem to make an anecdotal case that we are witnessing something extraordinary with the Cubs, I called on the world of science for confirmation.

Stephen M. Stigler is the Ernest DeWitt Burton Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Statistics at the University of Chicago. In a charming letter responding to my inquiry, Professor Stigler pointed out that over the span of World Series history, the Cubs have actually made a reasonable number of appearances (ten), "and the number of victories (two), while disappointing, is not astonishingly low." But he goes on to add, "What is striking is the paucity of recent appearances (and of course, of victories)." Taking into account the expansion of the league and assuming that every year was a clean slate, with every team having an equal opportunity, Professor Stigler says, "The chance that the Cubs would make no World Series appearances since 1945 is (7/8)^16 (9/10)^7 (11/12)^24 (13/14)^2 = 0.006, about half of 1 percent." In fairness, he goes on to point out that every year is not a clean slate—that the team doesn't change that much from year to year. If you assume that the team renews itself only every three years, for example, "the chance of no Series appearances since 1945 rises considerably, to 20 percent," a figure he describes as not remarkable at all. However, Professor Stigler concludes sagely, "if there is a lesson in all of this, it is that the Cubs would fare better if they changed the team yearly, at least until they come up with a winner!"

Now we're getting into a management strategy that John P. Murray could appreciate: Fire the whole bunch of them!

A PERSONAL NOTE

My son asks, his four-year-old face twisted with worry, "Why are you getting so angry, Dad?"

My wife: “It’s like being in love with a woman who constantly disappoints you."

In my earliest memories of the Cubs, my father is working in the garden outside our house. The car is in the driveway, the window rolled down and the radio tuned to a Cubs game. I am beside the car, excavating a gravel pit with a toy truck, and Dad has moved around the side of the house, out of earshot of the radio.

"Ernie just hit one!" I yell in response to a commotion on the broadcast.

"No kidding," he yells back past a plastic-tipped cigar clenched in his teeth. He stops digging and looks up. "Anybody on base?"

"The bases were loaded," I say, mimicking the announcer, though I'm not sure what the phrase means.

"Hey, that's great," he says, beaming, and I spend the rest of the game reporting loudly and inaccurately on the staticky bursts of radio enthusiasm.

I learned the rules of baseball lying on my stomach on the floor in front of the TV while my father, buried in his chair above me, explained the action. In one of the first games he annotated for me, the Cubs pushed ahead, then fell behind to a late rally. "They're gonna lose," I moaned and got up to leave.

“Just hold it, buddy," he said in a voice that simultaneously managed to convey hurt at my faithlessness and an admonition not to let it happen again. "The game's not over yet."

In those days, the Cubs held a sliver of promise in the new combination of shortstop Ernie Banks and second baseman Gene Baker. Baker and Banks produced a tying run in the ninth and the Cubs won in extra innings.

"I told you not to give up," he said afterwards. "I had a feeling they were going to win."

Over the years that followed, through eras painted with names like Drott, Lamp, Foote, and Trout, I've tried to imagine what my father felt that day. But my intuition has always screamed the opposite: Disaster lies ahead. Oh, there have been surprises over the years, flowers in the desert. A game in the early sixties when the Cubs' pitcher Glen Hobbie hung on for ten innings and then hit a homer to win it himself A no-hitter by Kenny Holtzman when the Cubs were cruising in 1969. At Wrigley Field in 1988, watching Greg Maddux pitch beautifully against the Mets, while my father, his heart failing, popped nitroglycerin pills as the game tightened up in the late innings (I thought, Are the Cubs finally going to kill him?). A year later, on the day the Cubs hoped to clinch a playoff spot, I got a call in New York, where I was living: Dad was being rushed in for an emergency heart bypass the next day. That evening, the phone rang again: It was Dad. He'd somehow gotten hold of a TV in the Rush-Presbyterian intensive-care unit, and while his surgeon stood by, furious, Dad announced, in a faltering, phlegmy voice, the final ecstatic pitches in the Cubs' victory. (The operation was a success and gave Dad four more years; the Cubs blew out of the playoffs in five games.)

Only once in all those years have I experienced anything approaching a feeling that they were going to win. In the sixth inning of the fifth and deciding game of the 1984 National League playoffs, with Rick Sutcliffe pitching (he'd gone 16-1 during the regular season), the Cubs were beating San Diego 3-0. Three innings to go. For some immeasurable moment shorter than a nanosecond, I allowed myself to think, Yes, they're going to make it, yes, yes, they're in the Series, yes. And in that instant, the demon was out of the box. Everything fell apart, climaxing in a ground ball that dribbled through Leon Durham's legs into right field.

Jim Frey was the Cubs' manager at the time. He's out of baseball now, but from his home in Maryland, he sounds weary over the phone: "I can still see that ground ball rolling into right field," he tells me. "I wake up at night and see it."

Amen, brother.

But enough dithering. Herewith, as best I can sort it out, is the anatomy of the Cubs' ignominy:

TIME FLIES

Harvey Walken, a former co-owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, famously remarked about the Cubs, "I guess any team can have a bad century." Presumably, he was joking. But, in fact, if you parse Cubs history, 87 years of failure slips by remarkably quickly.

To begin with, for a third or so of that time, the club was actually quite good, one of the strongest in the National League. It just always lost (seven times) in the World Series. That competitive team was largely the child of William Wrigley, the founder of the chewing-gum company, who bought a piece of the club in 1916 and acquired total control in 1921. "He was a guy who loved baseball, and he was a guy who was very much into winning," says Peter Golenbock, the author of Wrigleyville, a new oral history of the team. Wrigley hired smart baseball people and wasn't shy about spending for good players, and the team he built won pennants in 1929, 1932, 1935, and 1938. But William Wrigley died in 1932 and was succeeded by his son, P. K, an odd, private man who cared nothing for his father's beloved game. "P. K Wrigley had no interest in the team—he'd rather tinker with his cars in Lake Geneva," recalls Eddie Gold, the veteran Sun-Times sportswriter who's written five histories of the Cubs.

But P. K did have a knack for promotion. "When he took over the team, he fixed up the ballpark, made it clean, beautiful, and nice and safe, and he promoted coming to Wrigley Field and having a wonderful afternoon," says Golenbock. Unfortunately, he didn't much care how well his team played. P. K wouldn't spend money on players, and he alienated smart baseball executives (among those who left the team was Bill Veeck, who went on to a distinguished and occasionally uproarious career in baseball management). He let the Cubs' minor-league system—the R & D department of the baseball business—putter along in mediocrity. And he pushed crackpot ideas that disrupted the club—replacing the manager with a nine-member "college of coaches" being the most notorious. "Mr. Wrigley was a contrarian," says Jerome Holtzman, the Tribune's Hall of Fame baseball writer. "Whatever somebody did, he did the opposite. He didn't have night baseball because everybody else did." Overall, P. K Wrigley ran the team on his whims until he died in 1977.

For all but a handful of those years, the Cubs were terrible, and the team's management didn't seem particularly concerned. Jim Frey arrived a few years after the Tribune Company bought the team, and he recalls that some of the holdover Wrigley employees remarked on how there were limits on what they could do to improve the club. "There didn't seem to be a dramatic interest in winning a pennant or World Series," Frey says.

After P. K.'s death, his son William took over the team, but inheritance taxes were a problem. So in 1981—just after unloading Rick Reuschel, the best Cub pitcher, to the Yankees for $400,000 and two mediocre pitchers—he sold the club to the Tribune Company for $20.5 million.

In the 15 seasons since then, the Cubs have won division titles twice (in 1984 and 1989)—suggesting that things are moving in the right direction. "I'd argue that in the 15 years since the Tribune bought [the team], it's probably not that they've been so bad—their record is actually no worse than a lot of other organizations—it just seems that way building on the previous 35 years," says Bill James, the respected baseball statistician and analyst.

In other words (so this gentle analysis goes), the Trib hasn't owned the team long enough to erase the P. K. legacy, which Golenbock describes this way: "If you went to Wrigley Field, you'd have a wonderful time—and, oh, by the way, there was going to be a baseball game."

Still, 87 years is 87 years. (Question: If an infinite number of monkeys typing on an infinite number of typewriters would one day produce Romeo and Juliet, how many years would it take a baseball team of monkeys to win the National League pennant?) I pressed on with my quest.

PRETTY POISON

Over all those losing decades, ownership, management, and players have come and gone. The one constant (since 1916, when the team moved in) has been Wrigley Field.

Is it really possible that this landmark of taste and charm, this monument to everything that is warm and classic and human about baseball, is the cause of the problem? Well, no, but certainly management’s response to the park has guided the team toward mediocrity.

In baseball mythology, Wrigley Field is a little jewel of a ballpark in which the wind always blows toward the fences. In deference to this perception, the Cubs have traditionally larded their lineup with power hitters—players who could hit the ball high and far enough to ride the wind out of the park. The team never put a premium on speed. In my mind, Moose Moryn, the lumbering slugger of the late fifties, will always be the prototypical Cub outfielder. Indeed, in 1958, Moryn hit 26 home runs. But in his entire eight-year career, he stole all of seven bases. This is not a formula for success.

"The Cubs have been reluctant to get and accent speed; so has Boston. That's the greatest physical reason those two teams haven't won," says Tim McCarver, the savvy ballplayer turned broadcaster. "They just lack speed, and speed is the most vital thing in an offense."

What makes this particularly disconcerting is that the myth of Wrigley as a fly-ball hitter's paradise may be off. George Castle, the host of Diamond Gems, a syndicated baseball radio show originating in Chicago, studied the weather record at Wrigley Field between 1982 and 1986. "I found out the wind blows in two-thirds of the time," Castle says. "It's always been my contention that the Cubs never diversified their offense. They always seem to think you should load up with power, when two-thirds of the time the balls get hung up there in the wind."

The impact of Wrigley Field's greatest anomaly is harder to figure. Until 1988, when the Tribune Company installed lights, the Cubs were the only team to play no home night games. Even now, the club plays only 18 home night games, compared with 55 or so for most other teams. One line of analysis says the Cub players get worn out playing all those day games under the hot Chicago sun, and they have nothing left as the season winds down (a corollary holds that with their evenings free, the Cubs are out painting the town until all hours). Indeed, the heat factor has been widely retailed as the cause of the infamous 1969 collapse, when a strong Cubs team was, overtaken in September by the upstart Mets. "[Manager Leo] Durocher wore that team out," says McCarver. "He played 13 or 14 guys all year long. By mid-August, they were exhausted."

A variety of insiders dispute this analysis. "Who can't play baseball every day?" asks Gary Matthews, the former Cubs outfielder. George Casde points out that a summer day game in Wrigley Field is often cooler than, say, a night game in St. Louis. "With that wind coming in off the lake, I've worn my jacket in the press box in August," Castle says. As for the overactive nightlife, former manager Don Zimmer points out, "I would say that two-thirds of the players have families. They go home after the game. I was no angel, but when I did my running around with the guys, I did it on the road."

What's indisputable, though, is that the modern Cubs have an astounding pattern of falling apart late in the season. The numbers trip off Castle's lips: "'Seventy-seven, '79, '87, '88, '91, '92. In each of those years, they had a .500 or better record going into September [but ultimately fell below]."

Peter Palmer, the coeditor of Total Baseball, ran some statistics for me and found that between 1963 and 1995, the Cubs' overall record was close to .500 (that is, they won as many as they lost) in games played between April and August. In September, they sank to a miserable .450 (397-486). "The impression people get is that they do well up to a point, and then they kind of fade. And the statistics bear that out," Palmer says.

Clearly, something is going on. Castle blames the "body clock." "Cubs players are constantly shifting their body clocks back and forth," he says. "Everyone else in baseball is on an entertainer's schedule, where you stay up all night and sleep in the day." He theorizes that by the end of the season, the Cubs are out of sync.

Several doctors I spoke to were skeptical of Castle's diagnosis, though Joel Press, who practices sports medicine at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, says, "There may be something to it. One thing I know about athletes—they like a regular regimen."

Whatever, Cubs management has rarely developed and run the team to avoid the September swoon. How to do that? "Platoon," says Bill James. "Build a stronger bench. Give your pitchers a rest. But the managers have been like Durocher—they put their best players out there and ride them until they drop. They see they've got a chance and don't have the nerve to let up. I don't think Wrigley itself condemns them—it's how they deal with it."

There’s one more Wrigley Field factor to consider. This one leads into economics, once known as the "dismal science," and that expression was never more apt. Investment banker Paul J. Much puts it succinctly: "In some ways, you can have a tradeoff between having a great stadium with great ambiance or a winning team on the field." In other words, if you tore down beautiful little Wrigley Field (capacity 38,765) and put up a bigger stadium with more seats, more skyboxes, and more lucrative concessions, you would (presumably) make more money and thus be able to buy better players. "Stadium economics is frequently a key to fielding a winning team," says, Much, the senior managing director of Houlihan, Lokey, Howard & Zukin, a Chicago investment banking firm that specializes, among other things, in advising sports franchises.

Seymour Siwoff, of the Elias Sports Bureau in New York, agrees. "Eventually, Wrigley Field has got to go—just like the Bears at Soldier Field," he says. Last year, Siwoff points out, the Colorado Rockies, a new team playing in a new stadium, drew 3,390,037 people. In 1993, the Cubs' best attendance year, they drew only 2,653,763, even though they played before dozens of sellout crowds. "How much can you charge for the tickets?" he asks.

If told their only choice was between keeping Wrigley Field and creating a winner, most fans would storm Tribune Tower in fury—and it’s safe to assume the Tribune Company knows this. Though there was some low-grade rumbling about abandoning the ballpark when the Tribune Company was maneuvering to install lights in the mid-eighties, the talk has since subsided. Team president Andy MacPhail says, "When 1 interviewed for this job, I told the Tribune that I didn't want to preside over the demise of Wrigley Field." He swears it's not in the plans.

THE BURDEN OF HISTORY

Critical errors. September swoons. Decades of falling short. Nonetheless, Cubs players and managers insist that history doesn't weigh on the team and hold it back. "I never really got a sense that players got bothered by that," says Scott Sanderson, who was with the club from 1984 through 1989. He points out that in today's game, the players move from team to team and not many "feel or understand a sense of history."

"1 heard all that in '89," says Don Zimmer. "It didn't mean nothing."

Jim Frey says you can't play for the Cubs without confronting the jinx. "Anybody who goes in there has to read that shit day after day—and after July fourth, the writers start asking about it." In his mind, this is unjust. "I didn't have nothing to do with Durocher blowing the pennant [in 1969]," he says, his voice rising. "The players think, I can't help it if Ernie Banks didn't get into the World Series." Still, Frey insists, the questions were simply "irritating" and didn't affect the team's play.

Sports psychologists give a mixed assessment of the relationship between history and performance. "I think the players who deny [the impact of history] are deluding themselves," says Robert Schleser, director of the Center of Sport and Performance Psychology at the Illinois Institute of Technology. "The past does make a difference." Others cite an expectation of losing that could set in, particularly in pressure situations.

But virtually everyone I contacted said that good athletes could readily overcome a team's dismal traditions, and, indeed, we witness such successes repeatedly—the Indians last fall, for example. "No young player sees himself as a loser," says Rick Wolff, a sports psychology consultant who worked with that team. "We'd tell the kids that they were the ones to break out of the mold."

(My hunt for helpful sports psychologists led to a remarkable discovery. One day my research assistant, Tim O'Connell, bounced into my office with the news that he'd located a professor, Dr. James Dabbs of Georgia State University, who'd studied testosterone levels in athletes. Dr. Dabbs found that the levels increase after a win and decrease after a loss in both the players and the fans. Think of the consequences: On top of the general decline in sperm counts, this could mean that the Cubs' base of support will eventually disappear for failure to reproduce itself.)

Putting all this together, it's probably reasonable to assume that the psychological damage of the long Cub slide is felt less by the strapping young players than by the fans, who carry the baggage of defeat wherever they go (ever wonder why you can never get that first serve in when the match is on the line?). Nonetheless, even for professional athletes, there's an undeniable mystique—for better or worse—about the Cubs' condition. Here's Jim Frey, cooled off from the memories of those pesky writers: "For a guy that didn't play in the big leagues, I had a lot of good things happen to me in baseball. But I think when people ask me when the best time of my life was, it would be standing in [Wrigley Field, in September 1984] and watching them fill up the seats and knowing we were going to win the division."

THE LEANING TOWER

At the end of the 1981 season, the year the Tribune Company bought the Cubs, the seven teams with the worst records in the National League were Philadelphia, San Francisco, Atlanta, Pittsburgh, New York, San Diego, and the Cubs. Since then, all those teams have won pennants except Pittsburgh and the Cubs (and the Pirates lost in the playoffs three years in a row). This speaks well of major-league baseball’s recent tendency to spread the joy of victory, but it says nothing happy about Tribune ownership.

"You question whether they are more interested in winning or in payroll," says Eddie Gold.

There’s the issue that haunts the Tribune era: This is a company with some of the deepest pockets of any baseball owner, with revenues of more than $2 billion last year. Yet—many fans and critics believe—it refuses to spend for topnotch players to bring a winner. Indeed, so this argument goes, the Trib has no financial incentive to field a winner, since the fans will come out to Wrigley Field in any case. "I have a lot of friends who are Cubs fans," says Allen Sanderson, a White Sox fan and an economist who has studied the sports business. "I tell them, if you weren't so loyal, [the Cubs] would be better."

The issue is complex because, by several accounts, the top Trib executives are dismayed by the losing streak. "There seemed to be a real urgency to the Tribune people," Jim Frey recalls. "Two or three of them made comments about how they wanted to be the guy who brought a World Series to Chicago."

But the mix of corporate culture and baseball culture has not been easy—Cubs insiders, for example, have been known to refer derisively to the Tribune execs as Tower Guys, for their natural home in Tribune Tower.

At first, things looked bright. "They were considered a savior when they bought the team," George Castle says. The Tribune hired smart, cocky Dallas Green to run the dub. He started building the farm system, but he also made shrewd trades, leading to the division title in 1984. Following that season, though, he signed a number of veterans to expensive contracts. Most of them came up hurt or flopped. The Tower Guys seemed to grow gun-shy. After a few years, Green left, ushering in an era of churning management and nervous oversight by the Tower. "The guy that fired me, Don Grenesko, didn't know a baseball from a football," says Don Zimmer, who led the team to a division title in 1989, but was fired two years later. "You couldn't even carry on a good conversation on baseball with Grenesko, and he was president."

An agent who dealt with the team in that era sensed the problem. "There was too much of the Tribune, all that corporate stuff, and not enough baseball people. It became a very unhappy place."

The arrival of free agency meant that superstar players were available on the market (albeit for prices that were sometimes grossly inflated), but the Cubs rarely went after them. Worse, the team developed a great young pitcher, Greg Maddux, but dickered so ineptly over his contract that after the 1992 season, when he won his first Cy Young Award, he left for Atlanta, where he has won three more Cy Youngs and helped the Braves last fall to a World Series championship. Maddux's aggressive agent, Scott Boras, recalls dealing with the Tower Guys then running the Cubs: "I told them, 'He is not a print machinist. This is one of the most talented players in baseball. You're dealing with unique talent here.'" Boras adds, "This is a corporation that is seeded in the element that we don't pay labor to this extent. We can get someone else. We can get someone besides Maddux."

Several Cubs insiders say the Tribune Company's emphasis on the bottom line has sometimes taken the focus off winning. One former Cubs executive tells this story: "In 1985, we got off to a great start, and then the pitching staff all got hurt. Sometime in June, we hit a long losing streak. Soon it was up to seven or eight games. Each Monday morning, we'd have a meeting of directors of all the Cubs divisions—marketing, and so on. Don Grenesko was president then. He was a real bean counter. We go around the meeting, everyone giving his report. And when we get to Grenesko, he says, This is one of the great weeks in Cub history. We sold out every game. And Dallas kicked me under the table, as if to say, 'Look what we're up against.' The whole thing was, we made money." (Grenesko wouldn't comment.)

By one measure, the Tribune has done very well with the Cubs, paying $20.5 million in 1981 for a team that is now estimated to be worth between $140 million and $170 million. Of course, baseball has been beset by labor woes, and investment banker Paul J. Much says all but a small number of teams are losing money these days. Andy MacPhail has said the Cubs lost $15 million last year, and the team payroll of about $35 million was 12th highest of 28 teams. But fans have to take MacPhail on his word about the loss; the Tribune Company doesn't disclose the budget for the team. Several people I talked to were skeptical of Tribune accounting, particularly of the revenue credited to the Cubs for selling broadcast rights to WGN television and radio, which are also owned by the Tribune Company. Obviously, that programming is worth a lot—the Madison Square Garden cable network, for example, is paying the Yankees close to $500 million over 12 years for rights to their games. But since WGN’s payment to the Cubs is a secret kept in Tribune Tower, no one knows if the Tribune Company is just crying poor—a tactic to improve its position in the labor dispute with the players.

"It's a great conspiracy theory," says Peter Walker, the general manager of WGN-TV. Unfortunately, he adds, it's not true. The deal between the Cubs and WGN is "set up on a revenue-sharing basis," according to Walker. "We split the profits."

Still, many outsiders are suspicious. "All these things are being hidden," says Boras, who's not above a bit of rabblerousing. "It's not fair not to disclose to the true Cubs fans."

My friend Kenneth Labich, a lifelong Cubs fan and an editor at Fortune who has written about the elements of great teams, finally summed up the perception of the Tribune era this way: ''You have got to have a commitment to excellence by management. With the Cubs, you get the idea its sort of comfortable, like a picnic. They don't really need to win—the fans will come out in any case."

Full of moral rage and certainty, I finally marched up to Wrigley Field to confront Andy MacPhail. I found him in his office, an extraordinarily neat room in the bowels of the stadium. MacPhail comes from a respected baseball family and, at 42, he has already tasted World Series victory twice, with his previous team, the Minnesota Twins.

With the weary patience of someone who has had to do this dozens of times before, MacPhail explained to me why the rich Tribune Company won't drop a few extra million to buy a couple of great players. He said that baseball is a business, not a philanthropic exercise, and thus the team has to be fiscally responsible. What's more, he insisted that the only way to build a winning club is over time, by developing players. Buying free agents, he insisted, hasn't worked, except for those good teams that just needed a player or two to push them to the top. He scoffed at the argument that the Tribune Company is satisfied if the fans come out. "If ever there was a company that was motivated by winning, it's the Tribune," he said.

Then why not sign a top free-agent pitcher? I demanded. The Cubs weren't bad in '95. Maybe '96 will be the year! "There's only one way I know how to do it," he said. ''You build a solid foundation."

Through our hour's discussion, MacPhail was pleasant, reasonable, and articulate. Again and again, he returned to his mantra: You build a team over time by developing young players.

Finally, desperate, I did something cruel. I asked him what he would say to an 85-year-old Cubs fan, someone who's been following the team and buying tickets all those years, but who may not have the time left to wait while the Cubs try once again to put together a winning team.

A faint, wistful smile crossed Andy MacPhail's young face. "I'm doing the best I can," he said softly.

Moments later, I walked out of Wrigley Field, pushing through the administration door near the ticket booths at Clark and Addison. It was a gusty, bitter January day, and at that moment, the dreams of Cubs fans seemed as trifling and helpless as the scraps of litter being blown around the barren McDonald's parking lot across the street.

THEN WHY?

In thinking about the relationship between the Cubs and their fans, I sometimes recall a few lines from Paul Scott's great novel of British imperialism, The Jewel in the Crown (oh, all right, I remember them from the Masterpiece Theatre version). Scott was writing about England and India, but what he said could be applied equally to countless Chicagoans and their team: They were "locked in an imperial embrace of such long standing and subtlety it was no longer possible for them to know whether they hated or loved one another, or what it was that held them together and seemed to have confused the image of their separate destinies."

So let us return finally to John P. Murray, the frustrated fan who ran onto the field at the end of last season. In October he pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct. The judge sentenced him to 200 hours of community service, told him to make a $500 charitable donation, and ordered him to stay away from Wrigley Field for the 1996 season. When I talked to Murray in late December, he was cross at the way the incident had been portrayed in news reports. "They make me out like some madman, like the guy who stabbed [the tennis star] Monica Seles," he said. He'd only run out there to yell at Randy Myers. Still, Murray said, his life was returning to normal. And he'd been wondering: After he completes his community service and pays his fine, "if [the Cubs] make it to the postseason, would it be all right if I went?" He said he planned to ask the judge.