History tells us that great artistic movements beget great artists, but Intuit Art Museum has been challenging this idea for decades by asking, “Who gets to make great art?”

Formerly known as the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, the River West institution reopens May 23 after a 20-month, $10 million renovation, with the pithier name, triple the space, and an intriguing exhibition, Catalyst: Im/migration and Self-Taught Art in Chicago. Running through early next year, it showcases 92 works by 22 Chicago artists from 1930 to the present — an apt homage to the city’s early championing of outsider art, a genre that is approachable yet difficult to define. Museum president and CEO Debra Kerr describes it simply as work by “untrained creators.” It’s a movement that declares, audaciously, that art can be found anywhere and be made by anyone.

“There’s so much important work happening in spaces like public libraries, the park district, and artists’ homes,” says Alison Amick, Intuit’s chief curator. “These were artists who were making their own paths to create and work, looking for opportunities to build community and exhibit their art.”

The show provides a timely exploration of the impact immigrants have had on the city’s culture scene. Even so, Catalyst is more of a celebration than a political message: This is our city; these are our people. Look around you — art is everywhere.

Here are three of the artists featured in the exhibition.

Alfonso “Piloto” Nieves Ruiz

The 49-year-old has long used art to give language to his experiences, whether as a child growing up in a working-class neighborhood of Querétaro, Mexico; as an undocumented immigrant arriving in Chicago in 1996; or today, as the chef-owner of Zentli, a Mexican restaurant in Evanston. “I did art as a way of cleansing myself from all the things I couldn’t say,” Nieves Ruiz notes. Made with clay and discarded objects, his sculptures examine how in our attempts to further society we end up destroying ourselves. In his In the Name of Progress (above), Lady Liberty is represented as an Indigenous woman; chains encircle her body, severing her from the nourishment of Mother Earth.

Pooja Pittie

Growing up in Mumbai, India, Pittie was always making art. But it wasn’t until 2016, after completing her MBA at the University of Chicago, that she decided instead to fully embrace her passion as a painter and fiber artist. Pittie’s deeply personal work reflects her reality as a woman with a progressive form of muscular dystrophy. Her Be in Softness contains more than 240 knit vessels, each containing a handwritten message that expresses her doubts, fears, and questions. “A lot of the notes are tied to how I’m living as a disabled woman in this city,” says Pittie, 48. The work is both a conversation and a meditation, juxtaposing the difficulties of a body that’s slowing down with the tenderness of simply being.

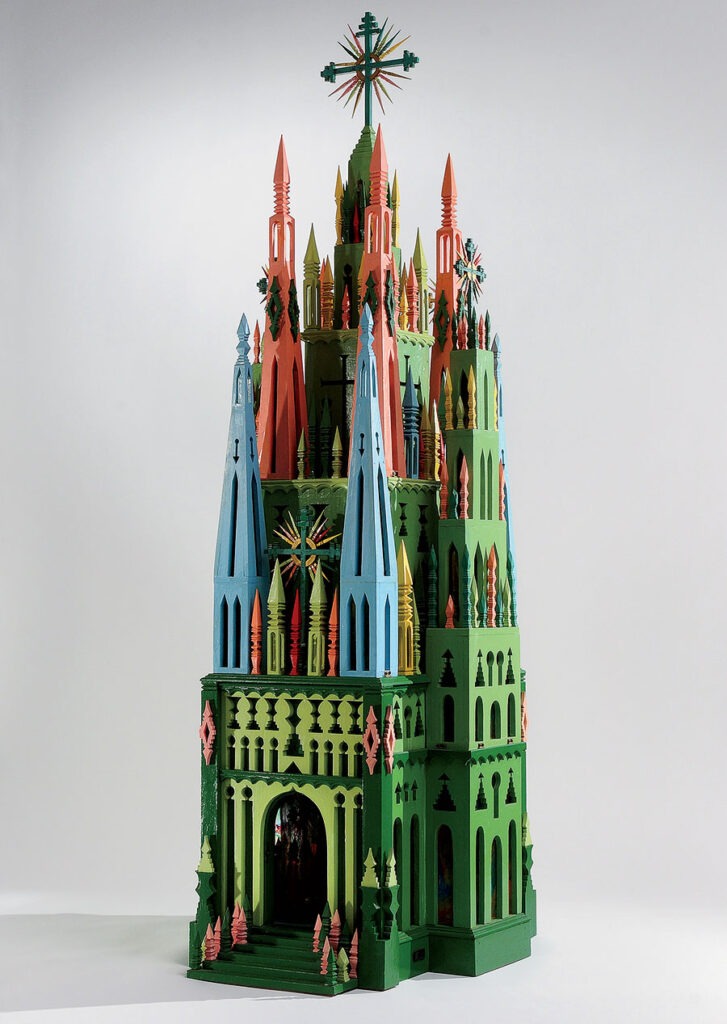

Charles Warner

Warner immigrated to the U.S. when he was 16, but his artistic era didn’t begin until he retired from a career as a carpenter and began woodworking in his garage. The Mundelein craftsman, who died in 1964 at around the age of 80, spent the last nine years of his life creating intricate, vibrantly colored, large-scale models of cathedrals reminiscent of his childhood in Poland. Using a jackknife and jigsaw, he hand-carved his structures, then meticulously painted them and even wired them for electricity. Even in their impressive specificity — small chandeliers hang above the altars, miniature pews line the naves — the cathedrals aren’t replicas. They are reflections of memory, an innate expression of his heritage.

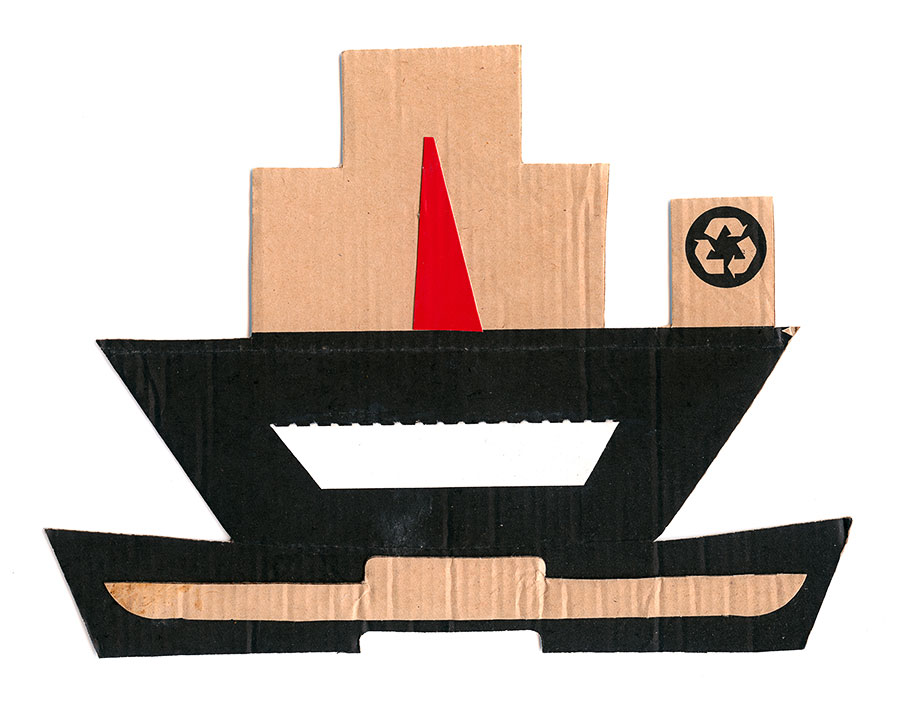

Thomas Kong

For years, Kong (born Kong Tae Kwon in North Korea in 1950) could be found at the cash register of his convenience store, Kim’s Corner Food in Rogers Park, cutting up bits of packaging, discarded advertisements, and other surplus material to make whimsical, almost compulsive collages. At first, he wanted something to decorate the store’s unsightly metal shelves, but soon every surface was covered with nearly 30,000 pieces, creating an unexpected but delightful installation. Kong died in 2023 and his store closed soon after — but not before inspiring a cult-like following of appreciators. Last year he was honored with a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo.