The sun sizzles, curling against the Dolton pavement as I round the corner on Manor Avenue, onto the 200 block of East 141st Place. Sherry Newsome sits on her stoop, the garden beds beyond its wrought iron railing brimming and lush. Her daughter has just pulled into the driveway. She parks and slides the door of her van open so she can sit on the bench seat, her legs dangling out.

“Do you know what time she gets here?” I ask from the sidewalk, second-guessing my thick denim shirt in this mid-June humidity. I tug at the collar.

“She’s usually here by noon. Sometimes earlier, if there’s a lot of people,” Sherry tells me, nodding to the empty police SUV across the street, in front of what had been, until recently, a nondescript midcentury brick cottage.

It’s quiet. In the stillness of the heat, flies buzz. The occasional car whizzes down Indiana Avenue, a few yards away. I hear the gentle rumble of a car starting up the street. A kid laughing.

“What happened to the blessings?” I ask.

Sherry’s daughter shakes her head. “Too loud and too early.”

Donna Sagna-Davis, who lives next door to the house we’re all now staring at, has taken it upon herself to create a kind of ad hoc welcome center, playing blessings from YouTube on a loop through her window. But without the breeze, and with the heat wave, everything — and everyone — feels a little more on edge. Or at least I am as I get back into my car to try to find a cup of coffee and kill some time.

When I return, after a tepid hour in a Dunkin’ Donuts with broken AC, a black SUV is parked, facing the wrong way, in front of the police vehicle. Inside the black SUV, Officer Latonya Ruffin checks her phone, glances out her tinted window. They’ll be here soon. The first ones always seem to arrive before noon. Throughout the day, more arrive in groups of two or three, like the couple who rode a tandem from Beverly. People from the city stop by, but also people from everywhere. A teacher came from Clarion, around 80 miles west of here. A journalist from Italy showed up one day.

They don’t do much, mostly stand in the front yard quietly. Sometimes they’ll sit on the stoop. Early on, one woman climbed the steps, placed her hand on the red front door, and prayed for a miracle.

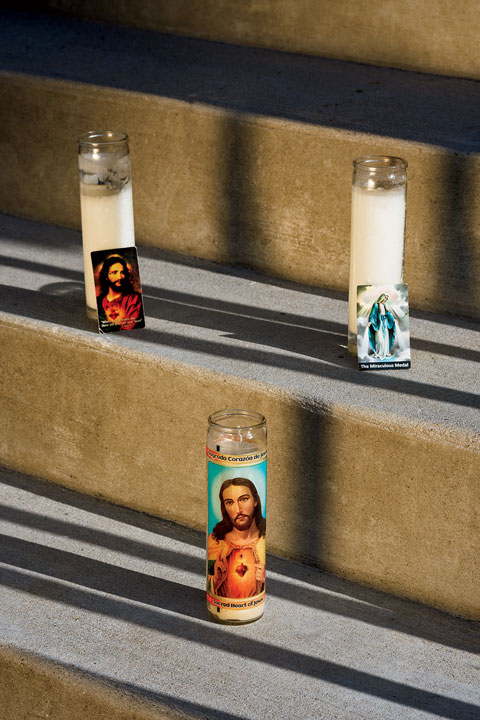

The house that sits quietly at 212 East 141st Place isn’t impressive. The roof’s shingles are peeling and in dire need of replacing. The unpainted, unsanded wooden front railing is abrasively new, the stamp from the lumberyard still visible. The concrete steps, also new, have started accumulating objects: rosaries, unlit candles, apples that are now browning. A silver crucifix rests on the windowsill.

Built in 1949, the house was bought that year by a family called the Prevosts. Louis Prevost was a navy man, fresh from the European front. His wife, Mildred, was a librarian. In quick succession, they had three boys: Louis, John, and Robert. The neighborhood was lively and a short distance from St. Mary of the Assumption in Riverdale, where the family attended Mass.

In 1990, Mildred died from cancer. Six years later, the family sold the house; the kids had already left. The youngest, Robert, was a missionary in Peru. When Pawel Radzik bought the house in 2024 for $66,000, it had already been through four different owners since the Prevosts. He gutted the place, putting in a new kitchen and flooring and replacing the original windows with vinyl double-pane ones. The house needed work — years earlier, the next-door neighbors caught folks selling drugs in the gangway — but by January it was ready to be listed for an optimistic $219,000, which Radzik later dropped to $199,900. No one was interested. Not even with its brand-new quartz countertops.

After a potential sale fell through in April, Radzik took the house off the market. Three days after he relisted it on May 5, the youngest Prevost boy, known to his friends as Bob or Bobby, walked out onto the balcony overlooking St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City. The house on East 141st Place, still empty, was no longer an unassuming flip. It was the house that raised a pope.

The eyes of the wiry middle-aged man from Texas grow wider as he walks briskly up the sidewalk toward the house, where I’m trying to read what’s inscribed on a small wooden cross that’s been left on the concrete steps (“Jesus — I Trust in You”). “An American pope,” he whispers. “Can you believe it?” In Chicago for a previously planned trip, he had gotten in his rental car and driven here. “Just to see if I could find it,” he says, then lifts up his phone to take a selfie in front of the house.

There’s the gentle ding of an open car door, followed by a high, cheer-filled voice: “You can get closer!” Officer Ruffin is leaning out of the driver’s side, her foot on the lawn. Even though she spends most of her workday sitting in an unmarked police vehicle, her uniform is pressed and impeccable. Not a strand of hair out of place, her nails painted bright orange. “You can go around back,” she says, waving toward the side of the house. She smiles and slides back into the car, its tinted window rolled up.

Ruffin sits and watches, making herself known only when she wants to, which is often. She gets out of the car to help take a group picture; rolls down the window to ask where people are from. When it’s quiet, she listens to music and checks in on her mom. Within the span of a few weeks, Ruffin became the unofficial greeter of Dolton’s first unofficial pilgrimage site.

“An American pope,” a man from Texas whispers. “Can you believe it?” Visiting Chicago, he had gotten in his rental car and driven here. “Just to see if I could find it,” he says, then lifts up his phone to take a selfie in front of the house.

There’s no precedent for something like this. No one really knows what to do with the childhood home of a newly elected American pope: not the eager but cautious outsiders who venture into Dolton to get a glimpse of the Prevosts’ old house, nor the village itself.

Almost immediately after Pope Leo XIV’s ascension, the house was swarmed with visitors; in quick order, Ruffin, a four-year veteran of the Dolton Police Department, was assigned to her post. Each morning, the marked squad vehicle that’s parked nightly in front of the home of Dolton’s new mayor, Jason House, is moved to 212 East 141st Place. Ruffin arrives around 11 a.m., sometimes earlier, in the unmarked SUV to begin her watch. She might head back to the station when there’s a lull or they need her for something, but Monday through Friday, until 6 p.m., this is her assignment.

Ruffin doesn’t miss having a regular patrol — she likes this style of community policing, talking with people, hearing their stories. There’s something about the house that inspires people to share. Most of the time, Ruffin is the one who listens.

Sometimes the conversation turns to the future of the house. “The archdiocese is getting involved,” a man named Michael Kelly says. “At least that’s what I read.” He’s wearing a red cycling kit, and a bike rests on his leg. Another visitor, Dennis Menke from Champaign, is looking at the walnut tree in the backyard. “I think he’ll really bring people back to Jesus,” he murmurs, kicking the uneven turf before ambling back to the front of the house.

As people come and go, I lean against the SUV and talk with Ruffin. “Someone told me the pope’s coming here in September,” she says, nodding. Someone also told her that investors bought up all the abandoned properties on the block. The neighbors tell her they don’t know what’s going to happen to them. The guy across the street has been there for three years — Ruffin says he told her he’ll move if the money is good enough. People tell Ruffin a lot of things. She has a knack for making people feel comfortable.

Originally, Ruffin wanted to be a pediatric nurse — “I love babies and seniors,” she says — but she fell into law enforcement instead. Police work is not the same as her first passion, but it’s not entirely different. She still gets to work with people and play some small part in making the world a better place. Sometimes there’s overlap, days when she works side by side with medical professionals. “We’re all first responders anyways,” Ruffin observes, almost as an afterthought, as if to say, Whatever happens, happens. You work with what you’ve got, you stop trying to anticipate the unexpected. A would-be nurse ends up a cop, guarding the childhood home of the first American pope. And as people can’t help but notice, a village disgraced is miraculously sanctified.