1 De La Salle Institute was the birthplace of the Chicago political machine.

After the Catholic lay group Christian Brothers opened the South Side private high school in 1889, generations of Daleys and other boys from nearby Bridgeport were educated there. De La Salle instructed them in communal loyalty, hierarchy, and obedience — all of which became machine traits. Think of it as civic grooming. The city’s political structure was even modeled after the Catholic Church: The mayor and Democratic Party chair were popes, aldermen and ward bosses were bishops, and precinct captains were priests.

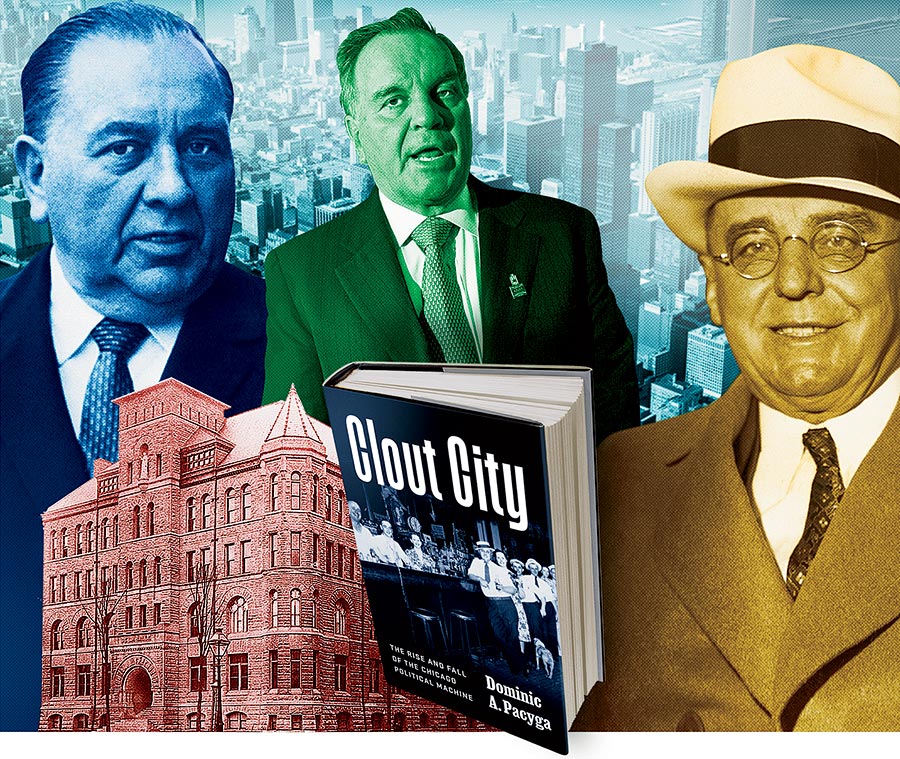

2 Anton Cermak (briefly) interrupted the Irish stranglehold on local politics.

A native of what’s now the Czech Republic, the city’s only European immigrant mayor, elected in 1931, attracted votes from Poles, Germans, and Jews. Once in office, Cermak supported Henry Horner, a Jew, in his successful gubernatorial run — “an extremely bold move to recognize ethnic groups often ignored by the old Irish party bosses,” Pacyga writes. His goal was to create a Chicago version of New York’s Tammany Hall. “Cermak built a powerful machine that would outlast and, in many ways, outperform the legendary New York City Democratic organization.” But after the mayor was killed in 1933, by a bullet meant for President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Irish regained control of the city. Five subsequent mayors were Irish, most of them from Bridgeport.

3 The Catholic Church began to undermine the machine.

The liberalization of the church in the early ’60s, under the Second Vatican Council, contributed to the liberalization of society — and the diminishment of obedience to both bishops and ward bosses. Here in Chicago, nuns even took part in a demonstration against the machine-appointed superintendent of public schools, protesting his segregationist policies. And Catholic parents, no longer required to send their children to Catholic schools, began to move to the suburbs for better public education, reducing their voting influence in the city. “Catholic loyalty to the teachings of both the church and the Democratic Party waned precipitously,” writes Pacyga.

4 Political nepotism here reached its peak under Richard J. Daley.

Helping family, friends, and neighbors was a core machine value, and the six-term mayor was unapologetic about doing so. A Daley-allied judge awarded lucrative cases to Daley’s lawyer sons Richard and Michael. And in the early ’70s, Daley transferred much of the city’s insurance premiums to an Evanston-based broker, Heil & Heil, which had just hired his son John (who received a nice commission on the deal). “If I can’t help my sons then they can kiss my ass,” Daley responded when the news broke.

5 Richard M. Daley brought the LGBTQ+ community into the fold.

Once gays became more politically active during the AIDS crisis, Daley began treating them like “a traditional ethnic group within Chicago’s political structure,” Pacyga writes. In 1989, after being elected to his first term, he became the first sitting mayor to march in the city’s Gay and Lesbian Pride Parade, which “would have been unthinkable for the older Daley,” Pacyga writes. He also supported the 1991 opening of the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame, personally handing out awards to honorees. And in 2002, he appointed the first openly gay alderperson, Tom Tunney, to represent the 44th Ward.