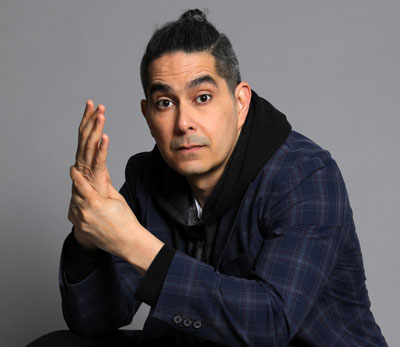

Dramatist Kristoffer Diaz is a New Yorker, through and through. He’s lived in both Brooklyn and Manhattan and teaches at NYU — yet considers the Windy City his second artistic home. “I’ve never lived in Chicago for more than three weeks at a time,” he says, “but I consider myself a Chicago playwright.”

That makes sense, given his long affiliation with local company Teatro Vista, which (in partnership with the now-defunct Victory Gardens) launched Diaz’s The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity. Set in the world of professional wrestling, the play had its world premiere here in 2009 and went on to become a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

This fall, Diaz is all over Chicago’s theater scene. The Alicia Keys jukebox show Hell’s Kitchen, which earned Diaz a 2024 Tony nomination for Best Book of a Musical, lands at the Nederlander Theatre for a three-week run in November. Meanwhile, American Blues Theater, where Diaz is an artistic affiliate, is producing his latest world premiere, Things with Friends, running through October 5.

Ambitious in both form and content, Friends is tricky to describe. It’s part dystopian thriller, part ambiguous drama, part dark comedy. While two couples gather on the 27th floor of a luxe Manhattan high-rise, the city below has sunk into turmoil: The George Washington Bridge has collapsed; the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, flooded; and everyone’s on edge about an impending storm.

Amid their wine drinking and steak eating (real steak, cooked live onstage), the four titular friends — spoiler alert — behave like they’re anything but. Although Diaz deliberately leaves certain things unsaid in this bleak satire, he lays down plenty of menace-coated breadcrumbs. “The apocalypse couldn’t keep us away,” says one dinner guest, ominously. Meanwhile, a narrator adds levity, addressing the audience directly while commenting about the characters.

Chicago talked to Diaz about creating a dinner-party play for the 21st century.

As I understand it, Things with Friends has been percolating with American Blues for two years. When did you first get the idea for the play? I wonder if there’s some Hurricane Sandy encoded into its DNA.

I forget how long exactly — over 10 years. I started writing it in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy [in October 2012]; I guess it wasn’t technically a hurricane. I had just had my first son. He was maybe 6 months old, and I have a very clear image of us in an apartment in Brooklyn, just looking at the sheets of rain coming in. It gives you a whole different sense of how powerful nature is. And then in the aftermath, I remember waiting on a super long line for gas, not knowing when things were going to come back to life. It’s not the first time I’ve been around something like that in New York City. I mean, we’ve had a bunch of blackouts; I was in my second year of graduate school for September 11. So, these things happen in New York, and then New York gets up and keeps on going somehow. So I started thinking about writing a play based around that.

How did you and your American Blues crew decide how to describe this play to potential audiences? In the marketing, you clearly want to avoid spoilers — which you cleverly get around with just six short sentences, ending with “We’ve already said too much.”

Most of the time, when I sit down to write something, I have a real clear sense of what it’s going to look like on stage, a real clear sense of what I’m trying to do. This was not that. I wanted to write a “people sitting on the couch drinking wine” play because I generally don’t like those plays. I wanted to understand what my aversions were, and what was resonant about this kind of play. I didn’t know how to do it, so I just started writing. It very quickly became three pages of stage directions to start the play. I didn’t think that that would make it into the final draft, but we’ve been workshopping this play in various places for many years, and a series of actors have come in and read those stage directions with such various ferocity, judgment — just cool approaches. We realized: In some way, that’s actually baked in, this commentary happening on top of the dinner-party play. So that was the permission to be really weird.

How many steaks and sweet potatoes does American Blues go through in a week?

[chuckles] I don’t think it’s a ton. The last I saw, it was eight sweet potatoes.

It looked like the actors were consuming a lot.

Yeah, they’re eating. It’s written into the play. There are stage directions that say things like, “I’m sorry, there’s no other way to do this. You’re going to have to eat it.”

Tell me a bit about your history with American Blues Theater.

[Executive artistic director] Wendy Whiteside was one of my first professional collaborators, from way back. It’s so great, being an artistic affiliate with a company in Chicago. It doesn’t exist in the same way in other cities, as far as I know. And my relationship with Teatro Vista is still intact. Between Blues and TV, it feels like I’ve got my foot back in this world, and I love it.

Later this fall, Chicago audiences will get to see another of your high-profile, award-winning works when the official tour of Hell’s Kitchen arrives. What were the challenges of writing the book to a jukebox musical?

Well, the appeal of working on this show was that Alicia Keys is one of the greatest singer-songwriters of all time. It’s so fun to talk about these two shows in connection to each other, because they’re so completely different. I come into the theater through musicals more than through plays. I grew up on musicals. I think it’s a surprise to some people when I show up to a theater meeting in my baggy hip-hop sweatshirts and jeans, and I’m like, “Yeah, let’s talk about Rent and how it changed my life.” You know, the wrestling guy is also the musical theater guy — but wrestling is kind of musical theater. They’re all of a piece in terms of theatrical vocabulary.