The video dropped like a bombshell. Late in the afternoon of November 24, 2015, two days before Thanksgiving, media outlets in Chicago and far beyond posted and broadcast the graphic footage, which shocked and enraged viewers, hundreds of whom soon clogged the South Loop intersection of Roosevelt and Michigan during raucous protests that lasted into the early-morning hours.

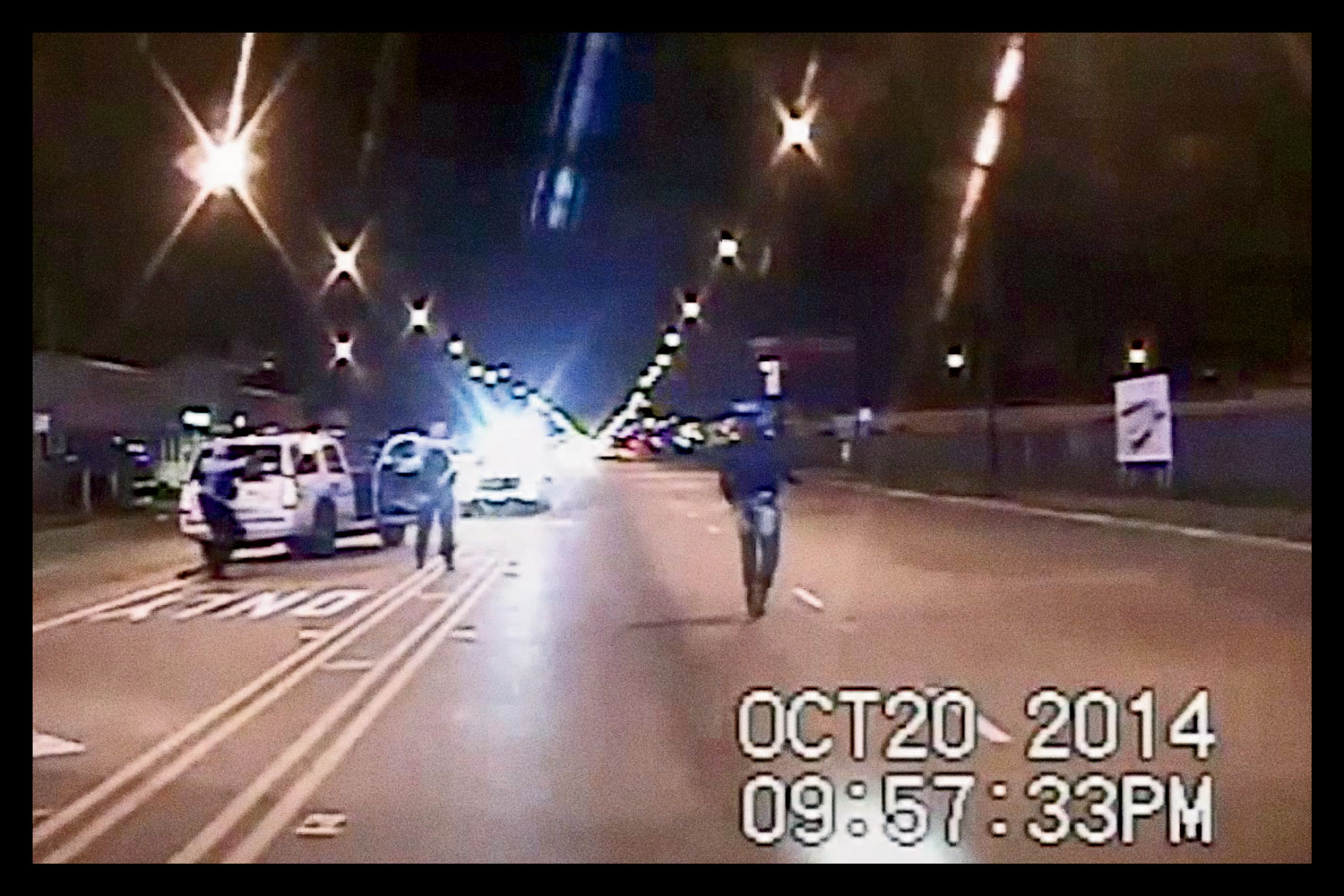

Captured by a Chicago Police Department dashcam and released by the city under court order, the roughly six-minute video is blurry, with muddy colors and blooming lights. It is also silent but for the faint, high-pitched sound of sirens. As displayed in flashing white type, the date is October 20, 2014, shortly before 10 p.m. The POV is that of a police cruiser, which rolls up behind a male pedestrian in the 4100 block of South Pulaski Road in the Southwest Side neighborhood of Archer Heights. He is 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, and he is holding a three-inch knife. The police are responding to calls he had been breaking into trucks and acting erratically. He will later be found to have a low dose of PCP in his system.

Wearing jeans and a dark hoodie, he runs down the middle of the street before slowing to a bouncy walk and drifting right. Eleven more seconds pass, then he stops suddenly. His feet together, he spins all the way around and crumples to the asphalt. Shot. One of the officers who’d pulled up in a squad car and approached McDonald had fired at him as McDonald passed by. That is 13-year Chicago Police Department veteran Jason Van Dyke, though his identity — and his history of excessive-force complaints — will not be revealed publicly for six more months. Van Dyke keeps firing — a rapid succession of 16 bullets in all — striking McDonald’s jerking body in the back, chest, arms, hand, elbow, neck, scalp, and leg. Within an hour, he will be pronounced dead.

Laquan McDonald’s death may well have become just another statistic if not for a yearlong battle by journalists, activists, and lawyers to unveil this video evidence of the brutal shooting. The consequences of their often intertwined efforts were wide-ranging. For the first time in nearly 35 years, a Chicago police officer was charged with first-degree murder for an on-duty killing. A U.S. Justice Department investigation uncovered a pattern of excessive force by Chicago police, leading to widespread reform measures. A police superintendent was fired. A state’s attorney lost her reelection bid. A mayor declined to run for office again.

A decade after their historic victory, the key players recount how they helped bring the transformative video to light.

The Narrators

Craig Futterman

Jamie Kalven

José Torres

Jeffrey Neslund

Shaddai Calloway

Brandon Smith

Matt Topic

“I got a call from someone in law enforcement. They’d seen the video and knew that the incident was being covered up. They told me it was an execution and that the police shot that boy like he was nothing but a dog in the street.”

University of Chicago Law School professor and founder of its Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic

My first intersection with anything related to Laquan McDonald was reading a couple of paragraphs about the shooting in the local papers. This was a story you’d see on a weekly basis because, at that time, Chicago police were shooting, on average, [close to] one Black person a week. The story was like, “Police see a young Black man armed with a knife, he comes at them, an officer shoots him in self-defense. End of story. Nothing to see.” And then three words that shut down all further inquiry: “It’s under investigation.” That meant you wouldn’t have access to anything about it. I could put air quotes around these “investigations,” because they were very much a part of the machinery designed to ensure police officers wouldn’t be held accountable.

Then I got a call from someone in law enforcement in Chicago. They felt they could trust me because of my long history at the U. of C. clinic. They’d seen the video and knew that the incident was being covered up. They told me it was an execution and that the police shot that boy like he was nothing but a dog in the street. They walked me through it frame by frame. It was the complete antithesis of what the police department had told the news media. Laquan was not threatening anyone and was moving away from the police when they first shot. Then, while the boy was on the ground, they shot him repeatedly while he writhed in pain. The source was tired of this mess and asked if I could help stop it. So I reached out to Jamie Kalven, who I’d been working with closely for 14 years at this point, and began to put in place plans to investigate this with my law students as well.

founding executive director of the Invisible Institute, a local investigative journalism nonprofit

The concern at that point was also the concern of the person who provided the tip — that the video would be deep-sixed. There was also a civilian eyewitness who had come forward to report what he had seen. That was José Torres. I didn’t have an exact address, so I spent time trying to track him down. I finally located him and came to his door several times before his wife answered and said she’d convey a message to him. But there was no contact, so I came back. It was kind of a great scene. It was raining lightly. I knocked on his door, and he answered. He was standing in the doorway and really upset to see me because he’d been given reassurances of confidentiality by the people he talked to. But even as he was alarmed by my presence, he couldn’t not tell me the broad strokes of what he had seen. Before parting with him, I left him my card and urged him to get in touch if he had more. Then I went to my car and immediately called Craig and said, “There’s a story here.”

“We were on an angle in the third lane over and had a clear view. I got upset. I said, ‘Why are they just shooting him? He’s on the ground.’ ”

witness to the shooting

Back in 2014, my son Xavier was 22 and really ill with Lyme disease, but we didn’t know what it was at the time. He was constantly going in and out of the hospital. We’re on the South Side, in West Elsdon, by Midway, and I have a sister-in-law who worked for a hospital up north, Lutheran General. We were on our way there, traveling north on Pulaski. It was just before 10 p.m.

When I got to 41st, I saw a police car coming in my direction, and I pulled over. Then police started surrounding the area. There were several police cars at that point. And I remember seeing Laquan McDonald walking in the middle of the street. The whole time, I was on the phone with my wife, just making sure my sister-in-law was aware we were on our way. I was describing everything I saw: “There’s something going on here. There’s police. There’s a guy in the middle of the street.” Shortly after that, I heard the gunshots and Laquan fell. We were on an angle in the third lane over and had a clear view. I got upset. I said, “Why the fuck are they just shooting him? He’s on the ground.” Xavier was freaking out. I remember him telling me “Let’s go!” as soon as the shooting happened. He goes, “We just witnessed this. We’ve got to turn around and get out of here.” He felt that the police were going to shoot us. But it took a while for us to do that because police officers were still arriving. You could actually see the blood running away from the body. We felt sick.

The following morning, I woke up and turned on the news like I always do. What got me upset was when [Chicago Fraternal Order of Police spokesman] Pat Camden came on and made some remark about, “What are you supposed to do with a knife-wielding person, have coffee with them?” I’m like, that’s BS, that’s not what happened. I called a buddy of mine, who was a Chicago police officer, and was going back and forth with him about what to do. He said, “Do what you think is right.” I was telling my wife, “I need to speak up.” She was worried: “You don’t know what’s going to happen. We’re going to have retaliation by the police.” But I couldn’t sleep. It kept eating away at me: What if that was my son?

It took me less than two weeks to contact IPRA [Independent Police Review Authority, a city agency tasked with investigating allegations of police misconduct]. I spoke to a detective there, and we made an appointment for me to come in. I was worried: “Am I going to be safe?” They promised me that everything is kept under wraps and my information wouldn’t come out. During the interview, they kept asking me if I thought Laquan McDonald was getting up. I said I didn’t see that. I said it looked like his body was bouncing from the gunshots. But they kept on pushing it: “Did you think he was getting up?” At the end, I finally said, “I don’t know. Maybe. But from what I saw, he was just moving because he was in pain.”

Shortly after, Jamie Kalven came by, and my wife called me. I was really pissed off. They said my name was going to be kept out of it, and here I had a reporter at my door. And if a reporter is able to find out my information, I know for a fact that the police know who I am. When Jamie came back, he told me he got a tip that the police were trying to sweep this under the rug. I was paranoid. I was looking behind him, looking around to make sure I wasn’t being set up for something. Like, I watch movies.

After Jamie left his information, I looked him up and saw exactly what he did. I contacted him and we met up. When he got involved, that’s when everything started unwinding. Jamie was really passionate about getting to the truth. And I’m like, OK, this is a good thing, he’s not going to let this go.

“Toni [Preckwinkle] pulled up in her car and beckoned me. The first thing she said was ‘16 shots.’ She is the first person who uttered that phrase.”

founding executive director of the Invisible Institute, a local investigative journalism nonprofit

Now I had two points in what proved to be a three-point stool. I had reason to believe that the video was pretty definitive of what happened. I had an eyewitness who was credible. So my next move was to try to get the autopsy. But there’s a period when an autopsy is not subject to FOIA [the Freedom of Information Act], until the medical examiner has concluded their final report. So I went to [Cook County Board President] Toni Preckwinkle, who I have a good relationship with, and asked if she could get top-level information. The Pat Camden account was that the young man lunged at the officer, and the officer shot him in self-defense. And it wasn’t said explicitly, but the impression was that one or two shots hit him in the chest and he died.

Toni’s chief of staff was [future Cook County State’s Attorney] Kim Foxx. So Kim went to the medical examiner’s office and got the basic information about the autopsy. By that time, it was around the holidays in December. One evening after dark, it was snowing and I went out for a run in Washington Park. And as I was running down 51st Street, Toni pulled up in her car and beckoned me. No niceties. No “Hello, how are you? Merry Christmas.” Toni cuts to the chase. And the first thing she said to me was “16 shots.” She is the first person who uttered that phrase.

University of Chicago Law School professor and founder of its Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic

Jamie and I posted a public statement on the web calling on the mayor to release the video and share the truth about what happened. We raised fundamental questions and called on him to do the right thing. But the city and the police department doubled down on “Nothing to see here.” There was also “What can we do to dirty up this kid?” Whatever they could do to bolster the narrative of a single shot in self-defense. But when we got the autopsy, it mapped each and every one of the 16 shots — a completely different reality.

founding executive director of the Invisible Institute, a local investigative journalism nonprofit

I knew I had enough to construct the narrative, so I started to write. I needed a national publication for it, so I sent a draft to Jacob Weisberg at Slate, where I’d written previously, and to Bill Keller at The New York Times, who was starting the Marshall Project [to report on abuses within the criminal justice system]. Jacob got back to me faster, so I ended up doing it for Slate, though Keller had a couple of suggestions that I incorporated in the piece.

It was exciting to break a story on that scale. But we were waiting to see how the Emanuel administration would respond. They had an opportunity to say, “In light of public interest, the gravity of this incident, here’s what we know about the case. Here’s the video.” The astonishing thing is, they just kept doubling down on this false narrative. Various media outlets made FOIA requests for the video and were denied, so I felt no need to make an additional request. I accepted, as most seasoned journalists did, that the city’s rationale — that the video figured into an ongoing investigation — would prevail in court.

attorney for McDonald’s family

The case came in through a defense lawyer we shared office space with. He knew the family and made the introduction. They had pictures from the funeral home, because the funeral home director was concerned about the number of gunshot wounds. But they were kind of blurry; you couldn’t tell what was what. So we opened a probate estate. In a wrongful death, a probate estate gives you subpoena power. We knew where the shooting happened, so we issued subpoenas to all the businesses in the area for any video footage: Dunkin’ Donuts, Burger King, the Greater Chicago Food Depository. We got a call back from the food depository, and the guy said, “Yeah, we’ve got video footage. The FBI was just here. You guys can come look at it whenever you want.” And the Burger King folks were really upset because IPRA took their entire server with all their video.

Craig Futterman was chasing the case, and he had an investigator talking to [McDonald’s sister] Tariana. Laquan’s mom, Tina Hunter, was upset: “Who’s this strange man in the apartment with my 15-year-old daughter?” We knew Craig from civil rights work. So we called him and said, “First of all, back off. We got the case. Second of all, what do you know?” He said he’d heard from a source that there was disturbing dashcam video, so we sent out a wave of subpoenas for all the police reports and 911 calls. Eventually, we got reports back showing that not just one but two dashcams had been preserved. So we sent another round of subpoenas asking for the dashcams. And somebody over at CPD made a copy, put it in the mail, and sent it to us.

Instantly, we knew this wasn’t your normal police shooting. This was a murder. We called the supervisor of the city’s federal torts division and said, “We represent the McDonald family. We have a copy of the dashcam video. Does the city want to sit down and talk about it, or should we just go ahead and file suit?” Because we thought it was pretty much a slam dunk. The city said, “Sure, we’ll talk to you about it.”

We told them we had to see the police reports and the detectives’ GPRs — their handwritten general progress report notes. So they set up a reading room and said, “We’ll let you come in and read everything. You can make all the notes you want, but you can’t copy anything.” We saw that there were three witnesses they had brought to the police station. And for one, a truck driver, there were like three scribbled lines: “I heard a bunch of shots, saw nothing.” When we got back to the office, we called him, and he said, “It was an execution.” He was in the upper cab of his truck, heard the sirens, and saw the whole thing. They kept trying to get him to change his story. When he wouldn’t, they finally cut him loose in the middle of the night. After that, we wrote a second demand letter to the city saying it wasn’t just a bad shooting — it was an attempt to cover it up.

Then we met with the medical examiner, who walked us through the gunshots. And it was an education. There was an entry wound to the top of Laquan’s right hand but no exit wound, which meant his hand was up against something. We knew it was the ground. He had shrapnel in his teeth from ricochets off the ground. Tina did not want to see the video, so we watched it and described it to her.

attorney for McDonald’s family

attorney for McDonald’s family

community activist

We’d experienced Trayvon Martin being killed by George Zimmerman in Florida. You had Michael Brown in Ferguson. You had [police killings] in Baltimore and New York. So the groundswell had started all across the country, but it had a special presence here in Chicago.

In April 2015, [Chicago police Detective] Dante Servin went to trial for the shooting death of Rekia Boyd. He was acquitted on a technicality. So Rekia didn’t receive justice. If something like that happened now, there would be press everywhere. But at that time, it was just Rekia’s brother, her mother, and some supporters in the courtroom. That year, the Chicago Police Department shot between 40 and 50 people, and nobody was held accountable. So for me it was a gumbo of rapid injustice. I felt defeated. I’m like, We’re losing on all fronts. We’re losing judicially and we’re losing politically. What can we do? I remember going into my apartment after the Servin trial, and I didn’t come outside for a week. It really put me in a dark space.

I talked with a civil rights attorney named Billy Joe Mills, and I told him, “Man, police have this video of a boy getting shot 16 times. We got to get it out. How do we do that?” He said, “We probably just have to FOIA it. But they might not release something like that, so you have to sue them.” He knew an independent journalist who did a lot of FOIA stuff. A couple of days later, he put me in touch with Brandon Smith.

independent journalist

Will was doing the really hard work of reaching out to and talking with the relatives of people who had been murdered by police, and I deeply respected him for that. He was the one who said, “I think this is going to be a big deal.” He pointed me to Jamie Kalven’s piece in Slate and [a segment by] NBC-5’s Carol Marin. That’s how we knew there was a video. Will was looking for someone to FOIA it. He found the right person.

At the time, I was working as a cook and dishwasher at a restaurant in Logan Square and doing journalism on the side, mornings and weekends. By that point, I had filed suit for three FOIA requests, and I kind of knew we would have to sue for this one, too. So did the lawyer I worked with, Matt Topic. I’d been his client for almost two years. If you win a FOIA case in Illinois, the attorney gets paid by the losing side. So the lawyer comes at no cost to you. As a cook-dishwasher, I wasn’t funding a high-dollar attorney for this. I just brought Matt a good case, and he was confident he could win it.

FOIA attorney

I had been eyeballs-deep in another case about surveillance technology, and that was where my head was at that time. So Brandon had to nudge me a bit. The point he made was that this potentially was going to be extremely explosive, and it was really important for the video to be released. Then I dug into it, and I completely agreed.

If it wasn’t for Jamie in Slate, I don’t know that the case would have gotten any further attention. That really set the table for someone to come in and say, “I’m not just going to ask them to release the video, I’m going to try to get a court to make them release the video.” Brandon didn’t understand why others weren’t pushing it, so he wanted us to push it.

founding executive director of the Invisible Institute, a local investigative journalism nonprofit

independent journalist

FOIA attorney

The city delayed him a few times, and it eventually got to the point where he said we weren’t going to accept any more delays. We had been preparing a complaint on the assumption that they were eventually going to deny the request. And we were getting ready for a point in the near future where if they weren’t going to produce it, we were going to take the case to court. Craig Futterman was a cocounsel. He and I had been looking for some things to collaborate on, and I thought there could be opportunities here to work together and give his students a chance to get involved in something important.

A lot of reporters, and a lot of lawyers representing reporters, were accustomed to the police department’s standard practice that if it’s an open investigation, they’re not going to release anything. And that’s not really what the law says. The law says not only does there have to be an open investigation, but they have to prove that releasing the requested information would interfere with the investigation. Proof generally means declarations or affidavits signed by knowledgeable personnel at the Chicago Police Department under penalty of perjury. But I think what happens more often is they dance around the issues, which is what they tried to do in the Laquan case. Delay is a huge tactic. The city did not want to release the video unless the feds were going to charge Jason Van Dyke. And there was no indication that that was ever going to happen, or that [State’s Attorney] Anita Alvarez was going to charge anybody.

independent journalist

FOIA attorney

The city never claimed there was a Chicago Police Department investigation, because there wasn’t. There was an IPRA investigation, a state’s attorney’s office investigation, and a federal investigation. And so they were relying on those things, but that’s not what the text of the statute says.

One of their arguments in the case, and one of the things that greatly offended me about their position, was that they said they still had to interview some witnesses, and if those witnesses saw the video before they’d interviewed them, they wouldn’t know the extent to which their statements were influenced by the video. At the same time, when you tell the public that Laquan was lunging with a knife, what are you doing to the witnesses who saw it differently? You’re telling them they’re sideways with the Chicago Police Department.

I knew that under the law, we were right. I also knew that the legal system is imperfect. This had been the CPD’s custom for a very long time, and a lot of judges were going to give that some deference. It was also a politically sensitive case, and that adds a whole other dynamic. I was confident the city would argue that releasing the video would create another Ferguson in Chicago and that any judge would want to think about that.

“When I came back from court that day, I was crying on the couch. The irony was, as hard as we fought for the video, I didn’t want to watch the murder of a 17-year-old kid.”

community activist

independent journalist

University of Chicago Law School professor and founder of its Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic

attorney for McDonald’s family

Hours later, on the afternoon of November 24, a day before the court-ordered deadline, Emanuel held a press conference at police headquarters in Bronzeville in which he urged calm. Coinciding with that, the city released the video. It quickly circulated online around the country and the world.

community activist

independent journalist

FOIA attorney

University of Chicago Law School professor and founder of its Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic

independent journalist

founding executive director of the Invisible Institute, a local investigative journalism nonprofit

The following March, Kim Foxx defeated Alvarez in the primary for Cook County state’s attorney. Alvarez’s loss was seen as a referendum on her handling of the Van Dyke case, in particular the holdup in charging him. And while Emanuel has sought to downplay the subject in interviews, the blowback from the delay in the video’s release is believed to have played a significant role in his decision not to seek a third term.

In October 2018, Van Dyke was convicted of second-degree murder and 16 counts of aggravated battery with a firearm. He was sentenced to 81 months in prison. Freed in February 2022, he served less than half his term.

community activist

I never in a million years thought this was going to get as much traction as it got. I just wanted to put pressure on Rahm. I wanted some type of justice for Rekia. I never thought there would be a Department of Justice investigation, Anita Alvarez being ousted, Garry McCarthy being fired, Rahm retiring, City Council changing over. So the video had maximum effect. And if you look at statistical data of how many Chicagoans were getting shot and/or killed by Chicago police around that time and you compare it to now, it’s really night and day. And without Laquan, you have no Lori Lightfoot. Without Lori, you have no Brandon Johnson. So it accomplished everything I wanted to accomplish, except Van Dyke being released from the penitentiary after serving only three and a half years. That part was a huge miscarriage of justice.

founding executive director of the Invisible Institute, a local investigative journalism nonprofit

University of Chicago Law School professor and founder of its Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic

witness to the shooting

founding executive director of the Invisible Institute, a local investigative journalism nonprofit

FOIA attorney