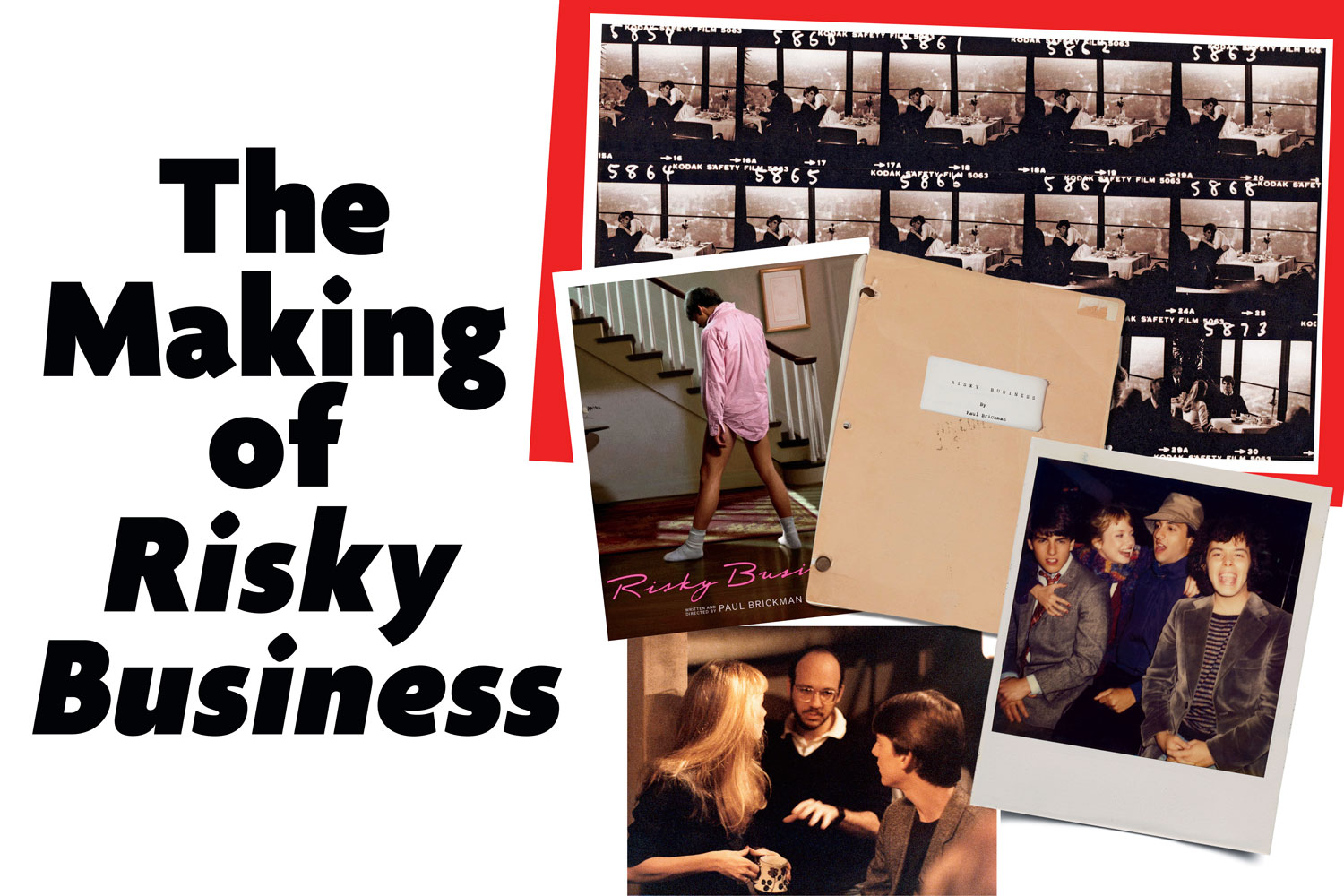

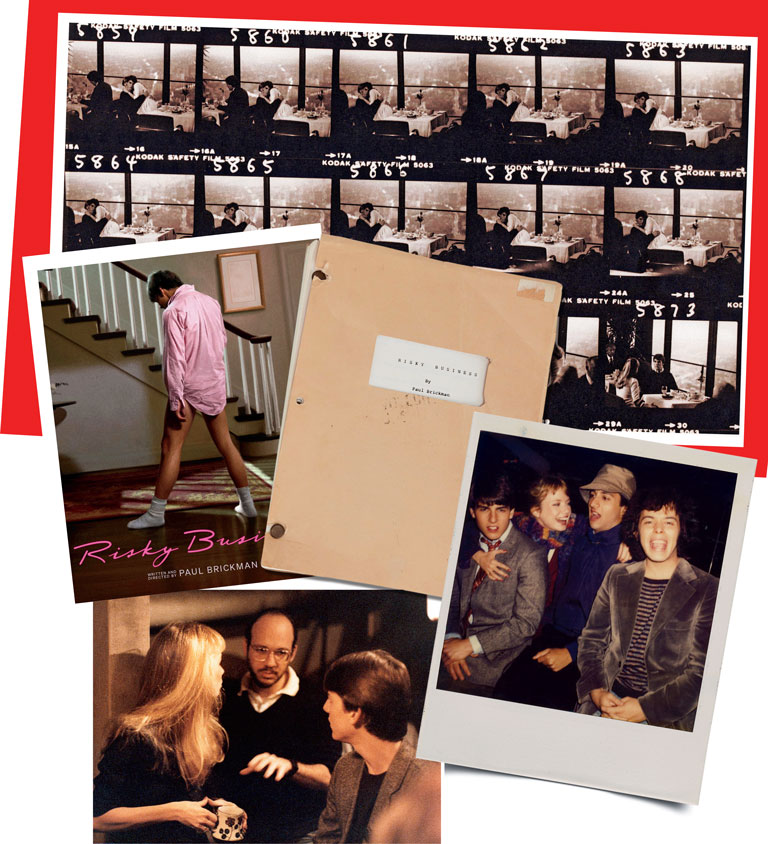

FFor Paul Brickman, the dream was always the same: to make a film for the youth of the 1980s that was smart and stylish and seductive. The Graduate for the Reagan era. While working as a Hollywood screenwriter in the late ’70s, the Highland Park native (son of syndicated Chicago Daily News and Sun-Times cartoonist Morrie Brickman) clashed with Jonathan Demme and other directors he felt weren’t fully realizing his material. Brickman quickly came to believe that if he ever wanted to see his unspoiled vision rendered on the big screen, he would have to not only write a cracking script but direct the picture himself.

Sometimes you gotta say, “What the fuck,” make your move. That seize-the-moment mantra has become one of the most quoted lines from Risky Business. It was also Brickman’s attitude as he set out for a rented cabin in a mountain town outside Los Angeles to write the film. He channeled his North Shore upbringing for the world of Joel Goodsen, a “white boy off the lake” (Glencoe, to be exact) so concerned about jeopardizing his future that he can’t have a guilt-free erotic fantasy, let alone actual sex. That is, until his parents go out of town and he has a fateful rendezvous with a Chicago call girl named Lana, who turns out to be the ultimate capitalist — and, for Joel, a masterful teacher of what he calls “the shameless pursuit of immediate gratification.”

As Brickman and producer Jon Avnet sought to sell studios on their coming-of-age art film — one that carried a broader social critique of the era’s unbridled capitalism and the toll it was exacting on young people — they bumped up against the vagaries of commercialism: companies interested in financing only vacuous teen sex comedies like the hit du jour, Porky’s, as well as a powerful executive who, at the eleventh hour, would force Brickman to compromise his vision.

Nevertheless, the movie became a surprise hit of 1983, and a relatively little-known 21-year-old actor named Tom Cruise made an instantly iconic slide in his socks and skivvies into the consciousness of the moviegoing public. As for Brickman, in the wake of Risky Business’s success, he turned down the chance to direct such films as Rain Man and Forrest Gump and helmed only one other feature, 1990’s underrated Men Don’t Leave, before all but vanishing from Hollywood.

For this behind-the-scenes account of the making of Risky Business, I talked to more than two dozen members of the cast and crew — virtually every major figure except the guarded Cruise. They recalled their extended residence during the summer of ’82 at the since-demolished Purple Hotel in Lincolnwood, Cruise and costar Rebecca De Mornay’s on- and off-camera boffing, the Method-acting mischief of a visiting Sean Penn, and even a brush with death on Michigan Avenue.

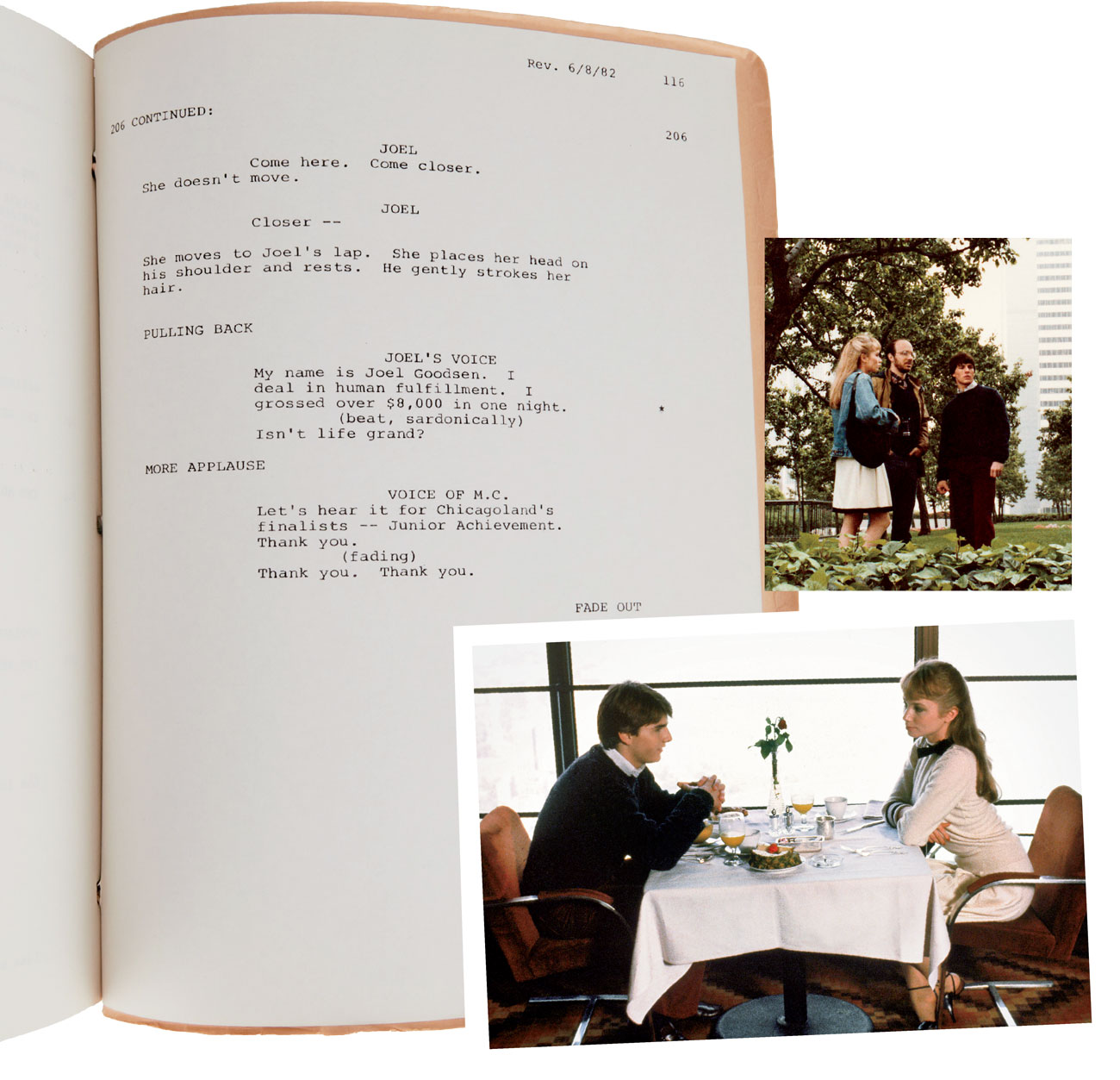

The reclusive Brickman, who admits he’s “from the J.D. Salinger school,” has given few interviews. He once sent me a bulleted list to explain why he avoids talking to journalists. He didn’t even do an interview with the Criterion Collection, which last year put out a restored edition of Risky Business that includes a version with his original ending. But Brickman, now 76, has been exceptionally responsive to my long-held fascination with his one hit. His words here are drawn from a recent conversation of ours, as well as one we had on Risky Business’s 30th anniversary in 2013 (portions of which were first published in Salon).

Now, to quote Lana’s advice to Joel: Go learn something.

Chicago is set up well for Risky Business, because you have the relative safety of the North Shore suburbs and you have the train line, which was a theme, connecting to adventure and darker elements in the city.

I“Let’s get this made”

Chicago is set up well for Risky Business, because you have the relative safety of the North Shore suburbs and you have the train line, which was a theme, connecting to adventure and darker elements in the city. That’s the journey Joel takes. It was an exploration of things not only geographically but of the darker side of himself.

Shooting the film in Chicago was always the idea. Paul was familiar with it, and that was very, very helpful.

The exterior of Joel’s house is three minutes from the house where I grew up. Shelton’s Ravinia Grill, where Joel and his friends talk about their futures, is where I used to hang out after walking home from school in the eighth grade. We’d go there and throw french fries at each other. Part of the car chase sequence with Guido, the killer pimp, goes by the Highland Park Theater, where I saw movies as a kid. The bank where the guys take money out to pay the call girls — I opened up an account there when I was 7.

The way I met Paul was I was producing my first film for Paramount. It needed a rewrite. I had read some of Paul’s stuff and thought he was a really good writer. So I asked him if he would take a look. He read it and said, “How much time do you have?” I said, “Two weeks.” He said, “I don’t think I could fix this in two years.” I went, Oh, I like this guy. We had lunch at Paramount shortly thereafter, and he mentioned the idea for Risky Business. I said, “I would love to be involved with that, if you think I could be of value.” Several months after our lunch, I got a call from Paul on the weekend. He said, “Remember that project? Would you read it?” I said, “Of course. Send it over on Monday.” He said, “Would you mind if I brought it up to your house now?” That was unusual. So he came up. I said, “Why don’t you walk around the house while I read?” And he said, “Would you mind if I read it to you?” When he finished, I said, “Well, Paul, this is certainly the best script I’ve read in a long time. What do you need me for?” He said, “I can’t finish it.” After about an hour or so of talking, it was clear to me a lot of what I could do for him was just be a third party who could say, “Look, this is good!” So we decided that I would be a producer.

While I was developing the script, I interviewed some call girls from the Midwest. They were so young. And what was sad was how optimistic they were about where they were going and what they’d be able to afford in life. I was looking at these girls, thinking, You don’t get it; you’re headed for trouble.

About eight or nine months of work later, Paul had finished the script. I said, “OK, let’s get this made.” At that time I was in partnership with Steve Tisch, so our company would be the producing entity with Paul.

I developed the project at Warner Bros. Upon reading the script, they passed and put it into “turnaround.” The working title was White Boys Off the Lake. I think the studio rejected that because it sounded like an off-Broadway play. So we started doing word association to come up with a new title. Jon and I shopped the film all over Hollywood. It was turned down everywhere.

The thing we were competing with, through the commercial lens of the studios, was that Porky’s had been successful.

I had no interest in doing that kind of film. What I was inspired by greatly was Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist, which I thought was beautifully rendered. I thought, Why can’t you present that as a film for youth and aspire to that kind of style and still have humor in it? That was the test: to meld that darker form of filmmaking with humor and a strong narrative. We were just about out of options when an entertainment attorney and friend, Peter Benedek, connected us with the nascent Geffen Film Company. I had lunch with David Geffen and he said, “Let’s make it.” After the production, we ended up gifting Joel’s mother’s crystal egg to Peter. He still has it.

David responded to the quality of the writing. He saw the humor in it, and he was not put off by the sexuality. And it was no small irony that David’s deal was at Warner Bros., so he was bringing the film back to a studio that had passed on it, but he had total control. So that began the journey. It would be quite a journey.

When we saw Tom, there was initially some trepidation because he looked like an Oklahoma greaser. Everybody was going, ‘That’s not the way a suburban kid from the North Shore of Chicago would look.’

II“There they are”

David said from the beginning, “It’s your movie, Paul.” But he was always going to have approval over the casting of Joel and Lana.

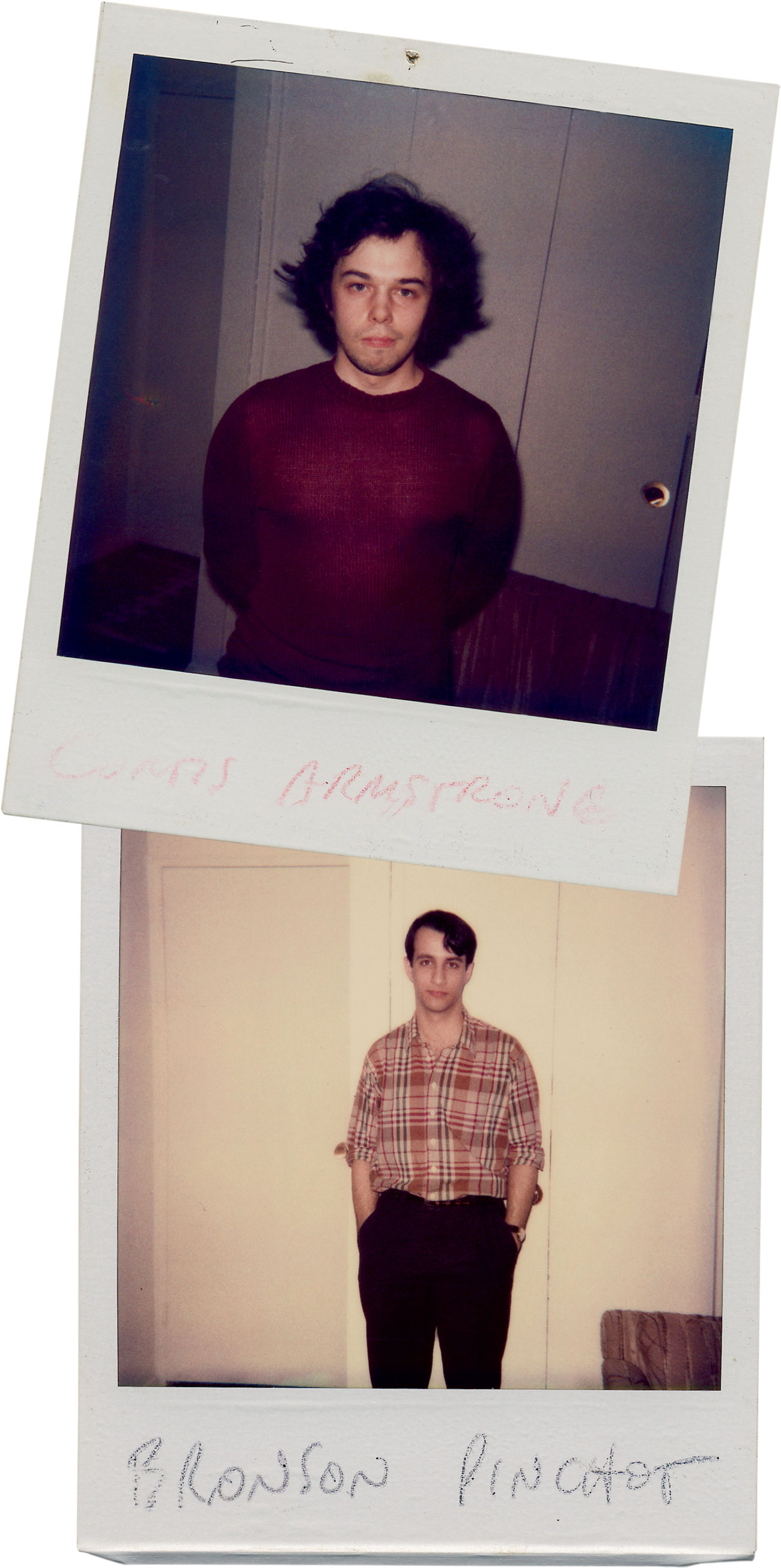

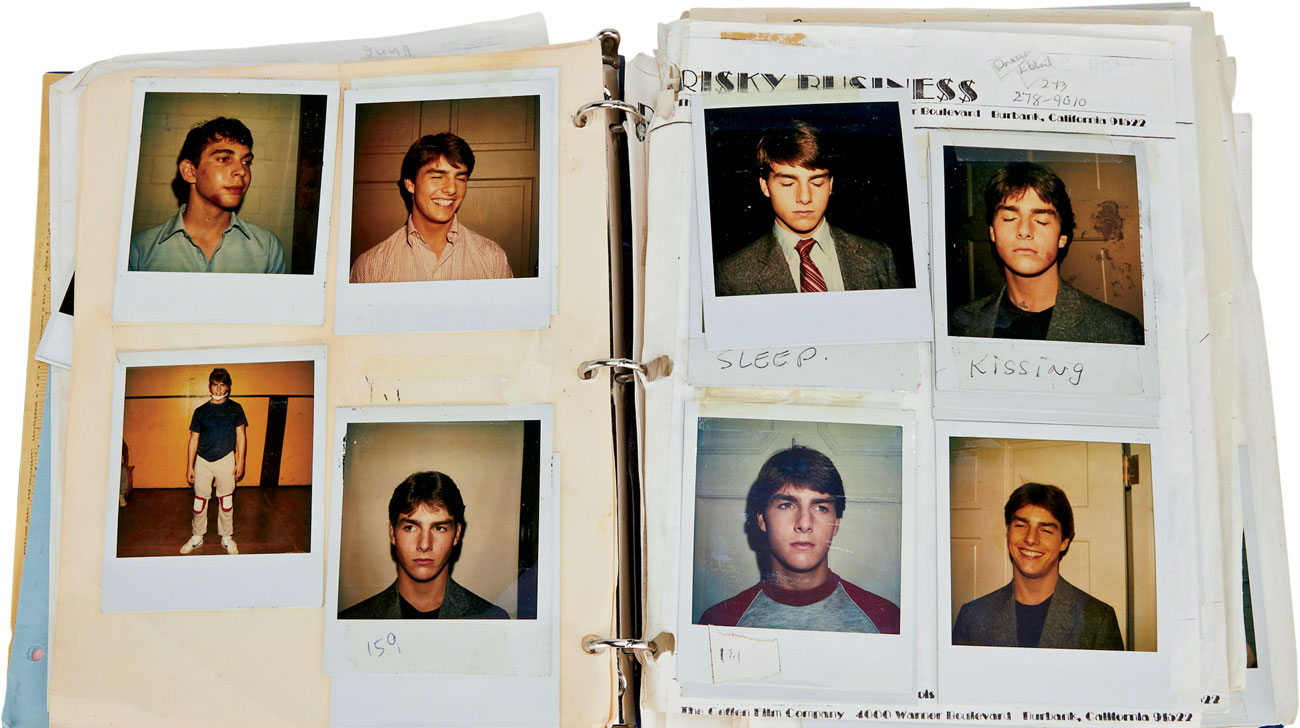

David wouldn’t greenlight the movie until he felt we had Joel and Lana. A huge swath of up-and-coming young actors on both coasts came in and read for Joel: Kevin Bacon, Sean Penn, John Cusack, Matthew Broderick. The same for Lana. We approached Michelle Pfeiffer, and she passed because she felt the film glamorized prostitution. Daryl Hannah also passed.

We had seen virtually every single young actor of the day — Tom Hanks, Diane Lane.

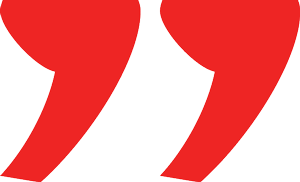

Jon and Paul then went to Chicago to continue the search there, and I stayed in New York and kept digging. They came out of Chicago telling me, “We met these two really special, incredible local actors” — Kevin Anderson and Megan Mullally.

I was so Joel. I had grown up in Gurnee, which is like 20 miles from where the movie takes place. I think Paul liked that. When Great America came to town, I was a sophomore in high school, and that was my first job: I was Bugs Bunny and other Warner Bros. characters. I read with Megan. We really connected, and they just loved us. We were flown out to L.A. on Easter Sunday in 1982 to screen-test for the two leads.

I remember sitting in the screening room, watching their screen tests with Paul. At the end, he said, “Well, Klop, what do you think?” And I said, “I don’t think we have them.” Paul said, “I think you’re right.” David Geffen agreed. That was a crushing moment, but we had to be honest. You look at actors up on the big screen, and they either jump out at you or they don’t. It had been months of work, and we were back to the drawing board. [Anderson ended up cast as one of Joel’s friends, and Mullally was given a minor role as a call girl.]

For Lana, we needed to cast the kind of woman that a teenager from the North Shore would do anything to be with.

Lana had to be gorgeous and tough — and she also had to have a vulnerability. You had to care about her, and you had to understand why Joel would risk everything for her while his parents were out of town. I called [actor] Harry Dean Stanton, who I knew a bit. He always had beautiful women around him. He recommended Rebecca De Mornay. She had a very minor role in Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart. That’s where he met her, and they were together at the time.

I was living at Harry Dean Stanton’s place. One day there was this script sitting on his couch. I saw the name: Risky Business. He was going to read for Guido, the pimp. Something about the title Risky Business just seemed like that was for me. So I laid down and read it. I had this overwhelming feeling about Lana: This is my part.

Rebecca came in, and she was very raw, very unformed as an actor. But she did have a quality about her that made her seem wiser than her years, as if she had been through a lot. And she was sexy. She came back the next day and read for Paul and Jon.

We had interviewed call girls of all different natures, and control was a big factor for why they did the job — liking to have control. There was a street quality, a toughness that made Rebecca feel believable.

I had lived by my wits in London for about a year before I got to L.A., waiting tables illegally without a green card and performing as a singer with bands. There was a strain in me, similar to Lana, of a deep melancholy about injustice within the system of capitalism. That’s why Risky Business is so affecting — it is a commentary on social injustice, on how the machine is oiled for certain people. Lana is the underdog of society, and I related to that. I related to the dignity that she carried herself with, even though she was a prostitute.

Within a day or two of seeing Rebecca, we got a call from Creative Artists Agency that Tom Cruise was in Oklahoma filming The Outsiders with Francis Ford Coppola but was coming into L.A. for a day and could we see him. We were like, “Of course.” He came in and he was very much in character for The Outsiders.

When we saw Tom, there was initially some trepidation because he looked like an Oklahoma greaser. He had a chipped tooth, big muscles, tattoos, greasy hair. Everybody was going, “That’s not the way a suburban kid from the North Shore of Chicago would look.”

We always did the opening monologue: “The dream is always the same …” He did it just like it was in the film — so great. Then I read with him for a couple of the scenes between Joel and Lana. He was terrific. When I first met Paul, he said, “What we’re looking for is Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate” — a young guy who is both a sexy leading man but also has a great sense for dark comedy writing, and Tom had that combination. He knew where the jokes were. He was sexy. He got all the irony.

When Tom came in, I was comfortable with him right away. I felt he embodied the role really well. I thought, Here’s a guy I can work with really easily. He appreciated the humor in the piece, and I thought that he would give a very credible performance, and you’d really believe the character. Tom is very expressive physically. That’s one of his strong suits as an actor. There’s a lot of body language going on with his performances. It serves him well, and it helped him in Risky Business.

Tom’s audition was singular. He would literally, in the middle of a reading, stop himself and say, “No, let me try this,” and then he would make an adjustment. He controlled the audition — and it wasn’t in an arrogant way. It was in a way of searching for the character. He had ideas. Part of what Paul liked about Tom was that Tom brought stuff to the table. Paul wanted a collaborator.

Tom had to fly right back to The Outsiders, but we wanted to test him with Rebecca. So we arranged on a weekend for him to fly back to L.A.

We scheduled a screen test at dawn at Steve Tisch’s house in the Hollywood Hills, with me working the video camera and Steve doing sound.

Tom flew into L.A. for our 6 a.m. screen test. I got up at 2 in the morning to get all my makeup on and get ready. Tom walked in, and he looked kind of disheveled. There was no real spark between us. I leaned into him and said, “Tom, you know what this is, right?” He said, “What do you mean?” I said, “This is the chemistry test, so we gotta get some chemistry going — fast.” I saw a light go on in his eyes. He was going to follow what I said. A connection happened in that moment.

We felt definite for the first time: OK, there they are. We sent the tape to David Geffen, who said, “Go make your movie.”

After I was cast, Paul took me into his car, and he played me the Phil Collins song “In the Air Tonight.” He said, “This is the mood for the movie.” It was exactly what I’d envisioned: a melancholy, aching love.

III“What kind of name is Cruise?”

David Geffen came to town only once, because he didn’t like the casting of Joe Pantoliano to play Guido, the pimp. We thought Pantoliano was perfect because he was menacing in a weaselly way.

Geffen was saying, “He doesn’t remind me of any pimp I know!” But Steve Tisch, Paul Brickman, and Jon Avnet all dug their heels in and protected me.

Tom and I were brought in two weeks prior to shooting for rehearsal. Paul had us also do theater games with each other to find our dynamic. That really helped cement my leadership role over Tom’s character. He had to be one step behind me all the time, and yet that is not something that is second nature to Tom Cruise. He likes to steer the ship. So it was interesting maintaining that leadership role, letting him know we’re going to do things the way I want them done. That dynamic had to work in the film.

When I found out the production schedule we would have in Chicago, the producers also told me Tom Cruise would be playing Joel. I’d never heard of Tom Cruise. I was scribbling all this stuff down, and I spelled his name Crewes. I thought it impossible that anyone would actually have the name Cruise.

I remember saying, “What kind of name is Cruise? Like cruising in a car?”

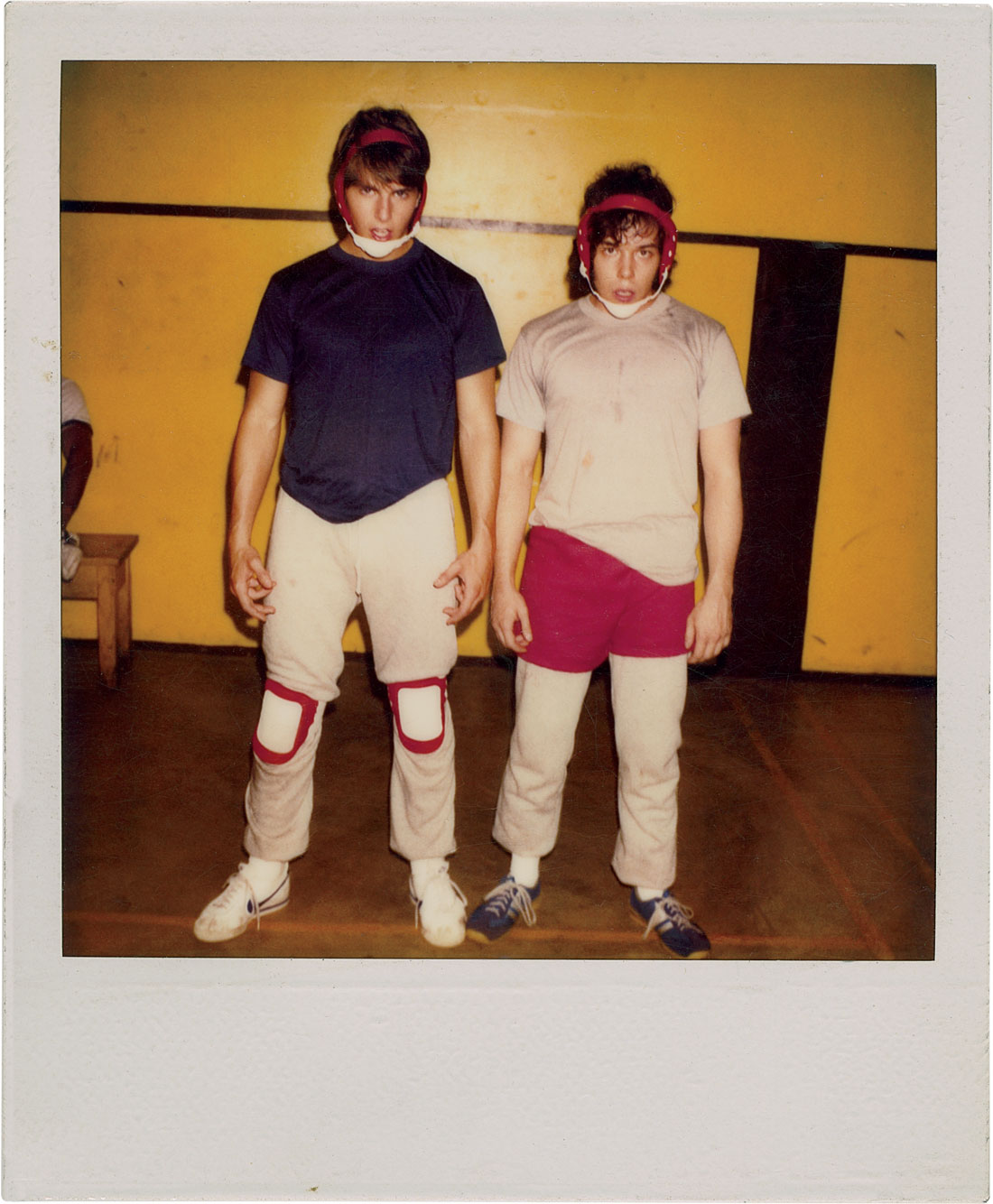

The rehearsal process that Paul Brickman had come up with initially involved all of the guys who were playing friends — Tom Cruise and Bronson Pinchot and Kevin Anderson and Raphael Sbarge and me — being picked up in a van and driven to a suburban Chicago shopping mall, and we would be left for the day at the mall. Paul’s theory was that we were supposed to be high school kids who were on the verge of going off to college, so we should be doing the things that high school boys do when they’re hanging out, which is go to the mall and the record store and the hamburger joint.

Tom and I realized right away we were incredibly different. I had just graduated magna cum laude from Yale, and — did Tom go to college? He was interested in Pac-Man, and I was interested in Thomas Hardy.

Tom had attended a Catholic seminary. He was literally planning to become a priest, and he had taken this left turn. He had already done Taps and The Outsiders, but only Taps had come out.

The main thing I noticed was Tom referred to me as Miles. He called everyone by their character name. At the time I didn’t know whether that was part of his process as an actor or just that he didn’t know my name.

Tom called me Barry. You think, Are you dead serious? Just turn it on when it’s time to turn it on! I had never been exposed to a Method actor before. I think it was something he picked up from Sean Penn, whom he idolized.

I lived in Old Town at the time. I split the second floor of a house for 50 bucks a month. I would take the L up to Skokie, and then get on a bus to get to the set. I was so green, just out of acting school. The other guys seemed so accomplished and loose. Bronson and Curtis had acted onstage in New York. Curtis was the coolest of all of us. His character, Miles, was the one who says, “Sometimes you gotta say, ‘What the fuck,’ ” and Curtis was like that in real life.

They housed all of us in a funny purple Hyatt in Lincolnwood — this dopey little hotel with vinyl wallpaper.

We were kept there for the entire run of the film, which was 11 weeks or something. There were weeks where I wasn’t shooting. I was just hanging out at the hotel. We would all get together at the hotel in the evening, or in the morning if we had an all-night shoot.

We couldn’t risk tanning, because we had to match for continuity. So we were often stuck in the hotel, bored as shit.

I went past Tom’s room one night, and there was literally a line of young women outside. It was sort of baffling to me because I didn’t know who Tom Cruise was. How somebody who wasn’t famous managed to get this following was beyond me.

Word had gotten out among the teenage girls who loved him from Taps that he was at the hotel. So there were lumpy teens sitting as if they were waiting to go into an audition or a dental appointment, with their backs against the wall, just sitting there cross-legged, doodling.

There was a lot of partying going on. It was a period of experimentation. I was probably drinking more than doing coke. It was mostly motivated by boredom. When you have a lot of time on your hands and you’re in a situation where there’s a lot of that going on, it can be a problem.

The scene at the hotel was the most fun. It was summer, with a group of young actors living together, drinking at the hotel bar, playing a lot of Pac-Man. There were little trysts happening here and there.

Harry Dean Stanton was there with Rebecca, and even Harry would be playing Pac-Man.

We were all in awe of Harry. He was the actor’s actor. He was an amazing swimmer, that guy. He would be in the hotel pool, and I would watch him swimming laps for hours. You’d think that maybe he’d gotten out at some point, but then you’d see that his towel was perfectly dry and folded next to the pool.

Tom was without a car during the production. So I took him out a couple of times. I was 26 or 27, he was 20. There was a Bennigan’s in the Old Orchard shopping center. I’d order a pitcher of beer and get him a glass.

One of the nights we went out, Tom was behind the wheel. We were driving down Michigan Avenue, and we got a little open road. So he was like, “Let’s fucking floor it.” He hit the gas, and we were going as fast as the vehicle could go. We were laughing, having a good time, and suddenly the light started to change and a huge truck pulled into the intersection. We were headed right for this fucking truck. And like out of a movie, Tom did a hard right turn, missed the truck, hit the brakes, and squealed the car to a stop into a parking spot on the right side of the road. Then he turns to me and gives me one of those huge Tom Cruise smiles. I was like, “Oh my God!” We almost didn’t make it that night.

IV“That was a hugely ballsy thing to do”

The interiors were shot mostly at a defunct high school in Skokie called Niles East. We built the sets in the school’s gymnasium.

John Hughes later used the same old high school for Sixteen Candles.

The first line in the film is “The dream is always the same,” and it was very much a conceit of Paul’s for the film to have the look of a dream. The first cinematographer was Peter Sova. He had done Diner, which we thought was a very good movie. But we hated his lighting. He would light the exteriors with big cranes with flat light coming down. It just looked so fake, so Hollywood. I said, “We’ve got to get rid of him,” and we did.

That was a hugely ballsy thing to do, because Paul hadn’t directed anything, but he wasn’t getting what he wanted.

We brought in Reynaldo Villalobos, who did a really good job. He lit with China balls that had a certain quality of light. It was very effective and essential. Rey had to leave, and we ended up with Bruce Surtees, otherwise known as the Prince of Darkness, who shot the last third.

Visually, I do appreciate something stylized, something abstract, when possible. Or, occasionally, something overromanticized, like wind and leaves blowing a door open.

Paul was so confident in his style and camera placement. Early in the film, he has a sequence where Joel’s parents are giving him instructions before they leave town — and it was all done from Joel’s point of view. It was showing the parents as alien to the world of a teenager. When the dailies came in and I looked at that, I thought, Fuck, man, this guy is bold.

Brickman was diligent about every detail. That scene where I say to Tom, “In a sluggish economy, never, ever fuck with another man’s livelihood” — during one take, I had a toothpick in my mouth. At one point, I took out the toothpick and put it under Tom’s neck, threateningly. After the take, Paul came up to me and said, “Listen, I don’t want you to do the toothpick. I want all the characters in this movie to be liked, and by doing that, you cross the line. I want Guido to be a likable pimp.”

The prop master on Risky Business was Jack Ackerman. He was an old guy who had worked as a kid wagging the tail on the lion from The Wizard of Oz with a fishing line. Jack goes, “We want to throw a pair of sunglasses on Tom Cruise.” So I run to the prop truck.

We were about to shoot the opening and closing shot in the backyard when my prop man showed me all the sunglasses in his kit. Nothing worked for me. So at lunch, Cruise and I hopped in my car and raced to the nearest optician in Wilmette. We tried on a bunch of pairs. I picked the Ray-Bans. I thought they looked both cool and comical on him.

V“He just knew”

We’d start shooting at 6 a.m., and Tom would be out running an hour or two before that.

Tom was trying to lose weight from having been in The Outsiders. He was running in one of those rubber suits, trying to get down to a normal size.

We were playing softball before filming began, and Tom broke a finger. He didn’t say anything, because he was worried it might interrupt the shoot schedule.

The guy was a machine.

Tom was focused and ambitious. This was a huge thing for him. He was serious about it. I didn’t get it because I thought he should be hanging out more. I was always just a “learn your lines and do it” actor, and then go to the bar. One night Tom told me, “I have to go prepare for an early shoot, and I also want to do some Bible reading before I go to bed.” It was said very seriously, but now that I look back on it, I’m not sure how much of it was a joke.

I felt a tap on the shoulder, I turned around, and he said, “Kessler, I’m Joel,” and he gave me that smile. I was completely taken. I don’t think anyone has ever hit me that hard with natural charisma. The “get off the babysitter” scene where Tom and I are kissing on a table, I was thinking, I can’t believe this! I said to Tom at one point, “I’m in a play in Chicago, if you want to come see it.” It was a play called E/R from the Organic Theater Company. He came to the show one night, and we went out afterwards. I had my first sushi dinner with Tom. We went dancing, then said a very cordial but sweet goodbye, because he had to get up early and go to the set the next day. But at that point, I had a complete crush on him.

On set, we were all in honey wagons — little trailers that have a toilet. I mean, small! Serial killers get more room in San Quentin. That’s probably the last time Tom Cruise ever set foot in a honey wagon. I remember him telling me that he was going to be a big movie star, and I was thinking, Well, that takes a lot of guts.

Once we were having ice cream sundaes, and Tom said, “I’ve got a sweet tooth, and I have to watch it. I gain weight.” I said, “Oh, lots of people do.” He said, “Really? Like stars? Like Al Pacino?” And I remember thinking, You don’t need to be worrying about Al Pacino level. That’s how [his ambition] came out — innocently. But that’s where he was pointed. He knew he was going to be a gigantic movie star. He wasn’t arrogant about it. He just knew.

The first time that fucking [Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll”] song came on and Tom went sliding across the screen, I just went, Who the fuck is this?

Tom and I went to the set by ourselves on a Sunday. We got silly, tried a bunch of moves, and had a lot of laughs. Our first attempt for the opening was to have Tom spring into frame from a trampoline off camera. That was too ridiculous, even for us. As a kid, I always loved sliding around the house in socks, so we gave it a try, and Tom nailed it.

When Tom came into frame the first time, what happened was he didn’t slide real well, so they worked on the socks and the floor slickness.

The Seger song provided the needed energy, a useful intro, and a fun lip-synch. But most importantly, in a slightly retro mode, I considered it to be timeless.

When you’re doing stuff like that, you never know how big it’s gonna be. It’s just another day at the office.

I think there’s a universal connection to that scene. People respond to that sense of freedom for a moment that’s so exuberant and so much fun.

It really captures the adolescent joy of having the house to yourself.

Tom and Rebecca were having an affair on the set. Everybody knew it. When the trailer was jumping, you weren’t supposed to go knock.

VI“My God, they’re naked”

When Tom and Rebecca shot the first sex scene, where the leaves blow in through the French doors, the filmmakers closed the set. Even the script supervisor came off the set saying, “My God, they’re naked — and they’re really doing it.” That’s when Shera Danese, who played the call girl Vicki, got the devil on her shoulder. She said, “We’re going to find a way in there to watch!” We climbed up the set and looked over the top.

I was completely in the moment and feeling a sense of power as I walked in the room in character. I felt that this was Lana’s arena. And I was game for some Risky Business.

Rebecca was drinking white wine to mellow her out. She was in these high heels, and then she inched off her underwear with her thumbs — but they got tangled in her shoes! It was supposed to be sexy and elegant, but she was tangled up. I started to laugh so hard that I shook the set, and then the assistant director came over and I felt this vise grip on my Achilles tendon. He was like, “I need to get you off this fucking set!” and hauled us out. Shera and I were limp with laughter. I respected Rebecca very much. I was also a horny 23-year-old not that far removed from the horny 17-year-old I was playing.

The chemistry you feel coming off the screen between Tom and Rebecca was very real.

Tom and Rebecca were having an affair on the set. Everybody knew it. When the trailer was jumping, you weren’t supposed to go knock.

At some point, Harry Dean Stanton was not so intent on Rebecca spending so much time with Tom.

I was in a relationship with Harry at the time and feeling drawn to Tom. We were very attracted to each other, which made the love scenes not unpleasant. Tom and I started to feel ourselves in our roles a lot. I’m trained in Method acting, and Tom was untrained, but he naturally becomes his roles. So at the beginning, there was sort of an antipathy that I felt toward him, honestly, and slowly feelings developed.

They were filming downtown at the Drake Hotel one day, which was literally two blocks from my apartment. So I walked over to say hi, and I was looking for Tom, who was busy. Bronson came up and goes, “Well, he and Rebecca are now officially together.” And I was like, “What?” It broke my heart.

VII“That’s actually Sean Penn in the car”

Bad Boys was also shooting in Chicago, and they had to halt production because Sean Penn broke his ankle. So Sean wound up moving into Tom’s room at the hotel, and he was there for ages. Normally, Tom, being Joel Goodsen, kept his room very neat and tidy. Suddenly, when Sean moved in, it became totally chaotic.

Sean was playing a hoodlum in Bad Boys, and he had gotten an actual tattoo for the character. He was in character all the time, which made him a bit scary to be around. One night we were at the hotel’s restaurant, and he lit a napkin on fire, then took one of those little paper doilies and literally made a little bonfire right there at the table. The waitress came and threw water on it, like, “What are you doing?”

Sean wanted to drive Joel’s dad’s Porsche, and he found an opportunity.

When the car is backing out of the driveway and stalls? That’s actually Sean Penn in the car.

The car’s engine conks out — that was a mistake. And then Sean started it up again. Paul realized after the fact, Oh, this is a happy accident. He used Jeff Beck’s “The Pump” underneath it, stopping the music when the engine stalled, which is just a brilliant use of music.

The Porsche 928 the film bought had been in a wreck and had no second gear. It was supposed to be used for all the stunts, but it was always in the shop. We got Tom a rental Porsche with an automatic transmission because he didn’t know how to drive a stick. We ended up doing most of the car chase with that one. I was driving the Porsche along Lake Shore Drive with Rebecca hanging out of the window while Guido was chasing us. Then there was a Porsche shell with no motor in it. That’s the car that actually went into the lake.

For the scene where the Porsche rolls down a hill onto a dock that collapses into Lake Michigan, we had to build a stunt dock at Belmont Harbor. There are a lot of things I can’t tell you about how I got that location.

Finally, after months of work, they gave us three nights to build and shoot. The problem was, I came back from another location to check on the dock they were building, and the production designer had put it in the wrong place — and the clock was ticking.

The production designer had chosen an area where there wasn’t a hill for the Porsche to roll down.

Avnet had to get them to work all night to disassemble the dock they had just built and move it to the proper location.

Paul was angry, but Paul never yells at anybody. He’s not a traditional Hollywood asshole. I said, “I have no idea how, but we’re going to get it done.” It was really a nightmare.

The first night we were supposed to shoot the scene, it rained. That was a dead night. The second night, it rained again. So on the last night, we did three nights of shooting in a single night. It was freezing cold. We had garbage bins with big fires right off camera, so the cast could race over after their takes and warm up.

Tom was in front of the car as it’s rolling down the hill, and I told him, “Just don’t get your feet under the wheels.” He sold the stunt great. Tom was a good athlete. He had been a wrestler in high school. I’m in the driver’s seat with a black cloth covering me so you can’t see me. I had my foot on the brake, just easing the car down to the dock. And then Tom jumped on the hood. That’s all him to the last beat when the car comes to the very end of the dock. We worried the pier might give way prematurely, because we’d built it to collapse.

It was a little bit dangerous. Tom would’ve gone in the water with the Porsche.

We didn’t get a chance to test that dock. I wasn’t sure when it was going to collapse.

When they pulled the release pins out from the hinges under the water, they had a tow truck pulling the cable that took out the pier pilings, almost like a weak knee. The columns buckled, the pier gave way, and the car went right in. It was one take and done. For the scene after that — where they go to the mechanic with the Porsche and the guy asks, “Who’s the U-boat commander?” — the filmmakers bought a bunch of trout from a trout farm and put them in the car, so that when the doors opened, like 30 fish came flooding out.

VIII“It was truly a party”

For the house party scene, the filmmakers were using a Steadicam, moving through the crowd. We were on the sound stage during a blistering hot and humid Chicago summer. There was loud music, a lot of very provocatively dressed women, and lots of shooting the shit.

It wasn’t like the director would say, “You stand here and hold this drink and laugh.” It was truly a party. People were mixing and mingling and having fun.

Tom would bring his big boom box to the set with all his cassette tapes. He was always playing Springsteen or something to get the actors and extras riled up.

The women who played the call girls — many of us knew each other because we were models from around Chicago. Megan Mullally was also one of the girls. The first time you met her, you knew she was going to be big.

The filmmakers picked me and my girlfriends from the Playboy models portfolio. I was at the top of the stairs coming down in a pink teddy, and the director was shooting up — so I actually had a crotch shot in a movie before Sharon Stone.

Jon Avnet grabbed me and said, “We’re going to do a scene. You just open the door and let the call girls in, and I’ll shoot it.” So I opened the door, and I reacted to all of the women coming in, and he said, “Perfect! That’s it!” And I said, “Oh, I can do much better.” He said, “I’m sure you cannot.”

Bronson is an astounding improviser. The scene where they’re putting Joel’s parents’ house back together after the party, they’re placing all of these knickknacks on a shelf, and Bronson says something to the effect of, “No, no, no. That doesn’t go there. You can’t mix centuries!”

The Princeton admissions interview scene in the den [during the house party] with Tom and me — Paul saw it as a pivotal scene, and he was very insecure about whether or not it was going to play. He said, “I don’t think the scene works. It’s just clunky.” I said, “Well, I’m being shitty to Joel with no sugarcoating. What if I say to Joel that we’re going to go over his résumé? I’ll read aloud these totally lame things he’s put on his application: recording secretary of the Spanish club, things like that — stuff that’s not getting anyone into Princeton. Let me be slimy with him.” Paul really liked that, and that’s what the scene became. At the end of it, Tom slaps me on the knee and says, “You know, Bill, there’s one thing I’ve learned in all my years. Sometimes you gotta say, ‘What the fuck,’ make your move.” The knee slap was an ad-lib. Tom just did that. And I look at him like, “Are you fucking kidding?” At the end of the house party sequence, there’s a moment where you see me leave with one of the call girls — a tall, breathtaking blonde. That wasn’t in the script. I told Paul, “The way to set up Joel getting into Princeton at the end of the film is to have me leave with one of the girls.” Paul was like, “Wow, yeah, that’s a great idea.”

The scene we didn’t quite get done on time was the first in the film — the shower dream scene. We shot it after the wrap party. That was a complicated one.

The shower was built inside the gymnasium along with the other interiors of Joel’s house. In the scene, which is Joel’s dream, the hallway to the shower appears to lengthen as he walks toward it, so he never reaches the shower. But it wasn’t the hallway that was moving; it was a shower that was on wheels, and as Tom Cruise began walking into the bathroom, they pulled the shower back. There was an eight-gallon water heater attached to the shower — and eight gallons didn’t last long. The steam you see was actually mineral oil vapor made with a diffuser. It was not a nice, warm shower. It was cold, and it was awkward. It was an 18-hour shoot. I never thought anybody would even recognize me, because by the end I looked like a drowned rat. On the last take, Tom was like, “Just go with me on this.” He made sure it would be the last take, because he kept on walking, opened the shower door, and got in, the water flowing all over his letterman jacket. So I can say I actually took a shower with Tom Cruise.

IX“It came across as pornographic”

When the movie was over, I went back to Los Angeles, and Tom went back to New York. One day I got a call from Tom. He said, “So do you want to meet me for coffee? I’m in L.A. Let’s see what we would feel if we just met each other off the street.” The relationship took off. And then Paul realized he didn’t like the love scene on the train. He got the money to go back to Chicago and reshoot. Tom and I were in the full flush of a relationship. How often is a camera taking a movie of you simulating a love scene while you’re actually in love?

If you look at the original screenplay, the scene was very vague. Paul had written, “Unrestrained passion against a window of exaggerated romantic imagery (to be devised).” He didn’t have a plan for how to shoot it to make it erotic.

Jon and I went to an Italian restaurant in Chicago one night that had the worst service I’ve ever had in my life. We were there for about three and a half hours. Out of that dinner, we came up with the initial concept of the flying train — an homage to a scene in The Conformist. It had Joel and Lana in a single CTA train car that at some point leaves the tracks and flies over Chicago. We shot it, but failed to execute it very well. It came across as pornographic. The film slipped into literal fantasy and became ridiculously romanticized.

It was as if he was trying to be Michelangelo Antonioni or Fellini. It did not belong because the rest of the picture is more naturalistic.

It was way too explicit. There was no mystery. The sensuality that ultimately took place wasn’t there. So Paul and I huddled, and I said, “They need obstacles. It’s too easy for them to get on the train and make love. The anticipation is probably as powerful as anything.”

In his rewriting for the additional shooting, Paul realized he wanted to build up to Joel and Lana being alone on the train. He added people to the train. Brilliantly, Paul got the wino homeless guy in there as the last remaining passenger, and the really nice touch of Joel escorting the guy off the train and compassionately covering him with a jacket. That was so Joel Goodsen.

We reshot it, but when we put it together, it was mediocre. It didn’t transcend into something that had a meaning outside of two people making love on a train. We still needed something that created sensuality and some style.

I started to play around with different speed changes, in order to take us out of real time by slowing down the footage. In my mind, it was bookending what was established at the beginning with the shower dream sequence.

Paul was using Music for 18 Musicians, the Steve Reich composition, as temp music, and Richard was creating a strobe effect. I said, “Look how sensual it is, particularly when Tom leans back and opens his mouth. Look how the Steve Reich plays with the sense of motion from a train.” This was before we went to Berlin to work with Tangerine Dream on the score.

Initially we sent some film to Tangerine Dream, and they came back with their first pass. It was clear they were trying to write music to a typical teen movie. The chord changes were like ’50s and ’60s teenage rock, and that’s not the direction I was trying to go. That’s when we got on a plane and went to Berlin. We hung out in Tangerine Dream’s studio for 10 days and knocked out the score with them. They worked in an old church. We’d start work around dinnertime and work through the night every night.

The first seven days, we got nothing useful. We were quite panicky. Then the eighth day, Edgar Froese comes in with a two-inch tape and plays “Love on a Real Train,” and we go, “Bingo!”

Tom, Rebecca, and I had gone out to dinner the night before the film came out, and I had told them, ‘Your lives are going to change radically now.’

X“The battle over the ending”

I got very close to achieving what I wanted to achieve for the first time, then the football was taken away from me like Charlie Brown and Lucy.

The battle over the ending was very disappointing. David felt that a more glib, upbeat ending was more commercial, and Paul and I were fighting for the integrity of the film. It was very tough on Paul.

In my original ending [a farewell-feeling dinner scene], everything gets flipped around totally. Lana is in control for most of the film, then Joel sees how vulnerable this young girl is and his heart goes out to her.

Lana says, “Why does it have to be so tough?” She’s never let her guard down in any way like that. Paul’s ending is so beautiful. Is it down? Well, yeah, it is much less buoyant than the theatrical ending [which shortens the dinner scene and adds a park scene that nods to a continued relationship]. What David wanted subverted the meaning of the movie.

It’s a small tonal thing, but it was very important for me to pull the themes of the film together. I fought like a madman to preserve the ending.

David was saying, “I’ll bring in a television director to finish it.” What I had said to Paul was, “By all means, stay with the film. Don’t let David beat you down so badly that you abandon it. Because you have to minimize the damage.” Paul had to write the new ending. The whole experience was brutal.

We had a screening where we had two theaters with two audiences looking at the two versions. It was the only movie I’ve ever worked on where I had to put together two versions.

The new ending tested a bit better — five or six points. It was enough that the argument David was making was not nuts or spurious. It was really disappointing to Paul.

We were very against it, Tom and I. We both really wanted it to stay true to Paul’s vision, but we had no choice.

I felt the film went out in a weaker form, and it really bothered me. Due to the dispute, our cast-and-crew screening was canceled. There was no premiere. The film opened in about 700 theaters. I got a call from Geffen. He said, “It’s a hit.” Tom, Rebecca, and I had gone out to dinner the night before the film came out, and I had told them, “Your lives are going to change radically now. I hope it’s what you want.” Unrelenting adoration can really twist you in some strange ways. It’s crazy to think that one day I was sitting in a cabin thinking of these lines of dialogue, and a few years later, these young lives were profoundly changed.