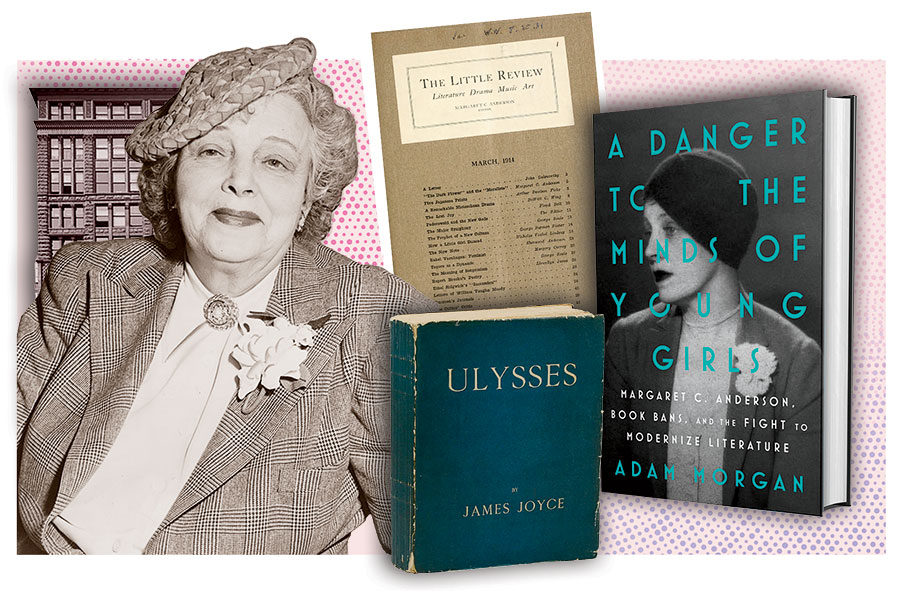

1 Margaret Anderson revolutionized literature on the cheap.

When she launched The Little Review in 1914, out of the Fine Arts Building, she created one of the first outlets for avant-garde lit. But the underfunded editor didn’t pay her writers, notes Adam Morgan in the new biography A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls. She argued that for a writer like Sherwood Anderson, it was “better to remain unpaid than for him to remain unprinted.” As Morgan points out: “The work of these misfits on the outer fringes of literature would become the new canon, but not until Margaret had made them acceptable to mainstream publishers.”

2 Her Uptown apartment was a hangout for radicals.

Emma Goldman visited Anderson’s place at 837 West Ainslie Street, where, the anarchist observed, “the entire furniture consisted of a piano, piano-stool, several broken cots, a table, and some kitchen chairs.” Anderson also hosted hobo doctor Ben Reitman and Wobbly labor leader Big Bill Haywood.

3 She was beautiful and knew it.

“It would be unbecoming of me not to know that I was extravagantly pretty … like a composite of all the most offensive magazine covers,” she wrote. Her many male admirers included Ben Hecht, who said his writings for The Little Review “may have been actually valentines composed for [her].” But, as Morgan chronicles, Anderson was a lesbian who coupled with her Little Review collaborator, Jane Heap.

4 For a while, she edited her magazine out of a tent.

When she was essentially homeless in 1915, she spent several months living and working with her team in five tents on a beach in Highland Park. Clad in a bathing suit, Anderson announced: “The next reporter who comes to this camp will receive a bullet. We came out here to be alone and we are tired of visitors.”

5 She introduced Ulysses to the world.

After Anderson moved in 1917 to Greenwich Village, Little Review contributor Ezra Pound sent her an unpublished novel by his friend James Joyce. “This is the most beautiful thing we’ll ever have,” Anderson told Heap. “We’ll print it if it’s the last effort of our lives.” They serialized Joyce’s masterpiece, knowing that the sex scenes could get them into trouble. In 1921, New York City authorities fined Anderson and Heap $50 each for publishing “lewdness and obscenity,” and their magazine soon folded. Morgan says Anderson doesn’t get enough credit for championing Ulysses, which “would change the very definition of what a book could be.”