This story was reported by Injustice Watch, a nonprofit newsroom in Chicago that investigates issues of equity and justice in the Cook County court system. Sign up here to get its weekly newsletter.

In early 1991, Timothy C. Evans was running for a sixth term as alderman of Chicago’s 4th Ward. If he had any premonition about his impending loss, he wasn’t showing it. “I expect to win without a runoff,” he told the Chicago Reader. “The race is not always to the swift,” he said, referencing an Old Testament verse. “It also goes to he who endures. And I expect to endure.”

Soon after, Evans lost in a runoff to longtime rival Toni Preckwinkle. Though Evans refused to issue “political epitaphs,” it seemed a deflating end of a public career in a city that had nearly made him mayor two years earlier. The Tribune described him as “washed up in city politics.”

But Evans was right to eschew epitaphs, because a year later he was elected judge. And within a decade, he had ascended to the top of America’s second-largest county court system. A far cry from being “washed up,” he was favored by the city’s elites for a state Supreme Court seat and lauded by the legal community for the reforms he had implemented as an administrator. Over the next quarter-century, Evans, 82, became the longest-serving chief judge in the history of the Cook County Circuit Court.

In September, his tenure came to a surprising conclusion when he lost his eighth reelection bid to Circuit Judge Charles Beach — a relative newcomer to the bench with no background in politics. As the county’s vast and complex court bureaucracy prepares for its first change in leadership in decades, questions about Beach and his plans abound. His election would have many believe the courts no longer need a career politician at their helm. But Evans’ story suggests otherwise.

Evans’ political acumen allowed him to endure as chief judge for 24 years and to enact significant progressive change in the inherently conservative courts, often for the benefit of the most vulnerable people to come through the system. His actions often seemed to come under duress, and his inaction was often criticized. But he achieved longevity in this role by keeping enough judges happy, absorbing public pressure, and weathering scandals unperturbed. His deliberative and self-assured leadership style was also well suited to the peculiar nature of the circuit court, an institution whose opaqueness is baked into law, whose principal actors are themselves elected officials, and whose bureaucracy is an entrenched extension of Chicago’s old political machine.

Evans grew up in segregated postwar Arkansas. As a child, he and his white friends would play football down by the railroad tracks, so the adults wouldn’t see them together. He earned money by cleaning an illegal gambling parlor where only white people were allowed. “But you still had to get along with those people,” he said. “Why? Because they tipped.” His mother, a teacher, moved the family to Chicago when he was 15, after Arkansas’ governor temporarily shut down public high schools in the state capital to prevent them from integrating.

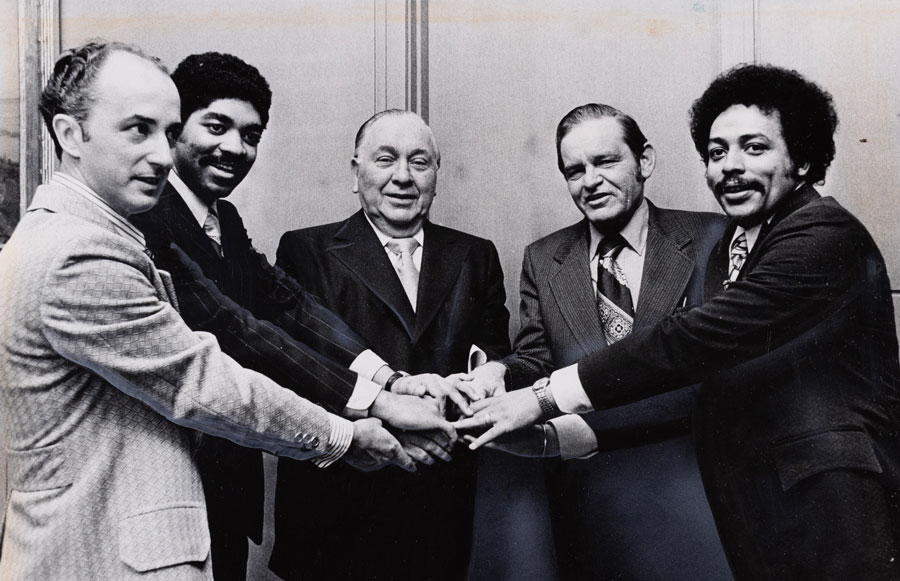

Evans’ father had played high school football with Glenn T. Johnson, who would eventually become the second Black appellate court justice in Illinois. In 1966, while Evans was a student at John Marshall Law School, Johnson ran to become a judge in the Circuit Court of Cook County, which was scarcely two years old. It was Evans’ first experience as a campaign soldier, and it ended with a celebration thrown by the Democratic Party at a Loop hotel. The winners were treated to cold-cut sandwiches prepared by Mayor Richard J. Daley’s wife. As the well-lubricated machine crowd dispersed in the wee hours of the morning, Evans reportedly whispered to Johnson: “I like this.”

Johnson introduced Evans to 4th Ward Ald. Claude Holman, one of a handful of Black City Council members and a self-described “puppet for Mayor Daley.” After graduating from law school, Evans, with Holman’s help, started a series of government jobs. When Holman died in 1973, Evans won the subsequent 4th Ward aldermanic election with a huge campaign war chest, and was backed by Daley to replace Holman as ward committeeman.

“Some people talked about me as a possibility to be the first black mayor of Chicago,” Evans, just 30 years old, told the Tribune after his victory. “But I don’t have any illusions along those lines. My horizons are set to be a good alderman, and that’s all I’m worrying about.” He also denied charges of being a machine stooge, assuring reporters: “I am not the mayor’s man.” Still, like most Black aldermen, over the next decade he was a reliable machine ally — until the 1983 election brought Harold Washington to City Hall.

Washington was looking for a floor leader in the City Council, and didn’t seem to care that Evans had a past with the machine. During a first term marred by the “Council Wars,” a targeted obstruction of Washington’s legislative agenda led by white South Side aldermen, getting anything done required buy-in from the opposition. Evans — likable, eloquent, well-dressed, and exceedingly polite — was the best bridge-builder in Washington’s camp.

“The skills he had as a get-along guy worked,” recalled David Orr, a key Washington ally on the council. Evans was not only a well-known colleague to the machinists (politely referred to as “regular Democrats”) but was “smooth,” Orr said. “He could travel well between the regulars and a smaller number of independents.”

When Washington died unexpectedly less than a year into his second term, Evans was seen by many as the rightful successor to the mayoralty. But the machinists on the City Council instead installed Eugene Sawyer, a Black alderman they thought they could more easily control. They turned out to be wrong, as Sawyer continued the Washington agenda. Evans pushed for a special election in 1989 and ran a high-profile but “penniless” campaign as the “Harold Washington Party” candidate.

Evans and Sawyer were trounced by the machine, and Richard M. Daley took over the city for the next 22 years. People who were active in Chicago politics back then still wonder if Evans was serious about becoming mayor: How badly did he want it? Had he made a deal with Daley to run and divide the Black community? If so, in exchange for what?

Reconciling with Daley and the rest of the white machinists would have made political sense for Evans, Orr says. The regular Democrats were emerging from the 1980s with a sordid reputation for racism. Meanwhile, Evans, who was still very popular in the Black community, no longer had a patron or access to the levers of power, especially once he lost his seat on the City Council. He and his old opponents stood to gain by standing together.

“That doesn’t mean Tim Evans is a sellout,” Orr said. “It just means he’s who he is: He’s a smart politician.”

Throughout his time as alderman, Evans maintained a solo law practice and represented clients in estate, family law, and personal injury cases. But he wasn’t content to live a life outside of public service.

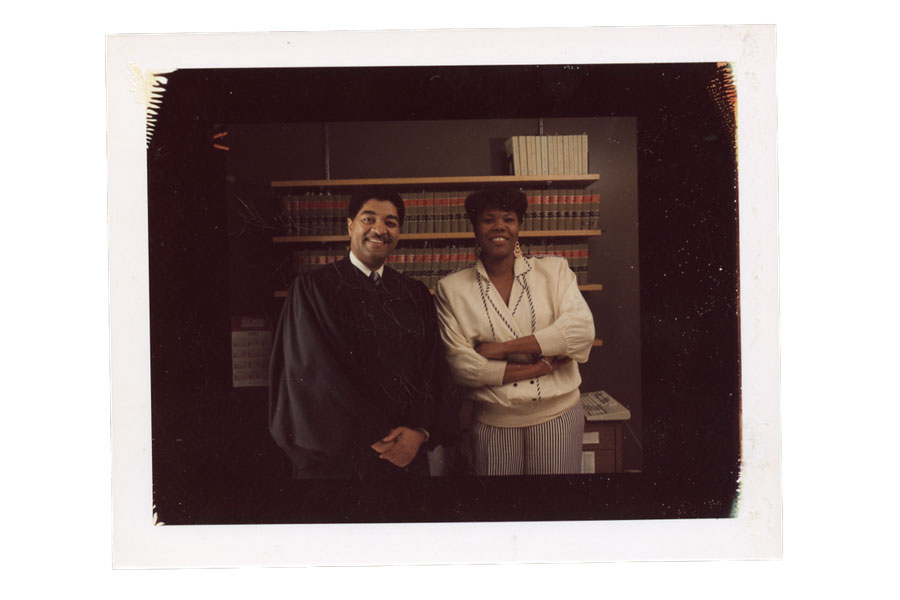

Evans had not dreamed of becoming a judge, he said. But in 1992, Cook County held the first elections in its new judicial subcircuits, which had been drawn to bring more diversity to the bench. It presented Evans with an opportunity. “That’s how these things happen for me,” he said.

The Chicago Bar Association and Chicago Council of Lawyers found him qualified for judge, and he won by almost 14,500 votes. Preckwinkle, who had backed Evans’ opponent in that race, observed that his rise to the top of the courts in the next few years was “meteoric.”

Evans was sworn in at a challenging moment in the circuit court’s history. On the criminal side, the war on drugs and record-high violent crime had created an unprecedented caseload at the main courthouse at 26th and California, exacerbating its reputation for dehumanizing conditions and wrongful convictions. The juvenile courts had been declared an “unworkable failure” by a task force of lawyers. The court was still reeling from two massive corruption scandals uncovered by the FBI, which had led to the convictions of 17 judges and dozens of other officials. Chief Judge Harry Comerford, only the second person to hold the position since the circuit court was created, was not implicated in the corruption but was under pressure to bring order to the courts.

The people who worked under the chief judge — whether judges themselves or the thousands of employees who administered everything from the county’s probation programs to psychiatric evaluations of criminal defendants to the guardianship of minors and older adults — were part of the Cook County Democratic Party’s patronage network. Although a lawsuit brought by good-government advocate Michael Shakman beginning in the late 1960s had delivered substantial blows to political hiring practices in much of city and county government, the Office of the Chief Judge was never subject to the Shakman decrees. No federal judge or court-appointed monitor kept watch over how jobs were doled out there. Evans’ twin daughters began working for the courts soon after he was sworn in and remain in administrative posts to this day.

Just like the rank-and-file staff, chief judges weren’t nobodies nobody sent — they were a “vital link in the patronage chain,” as a political editor at the Tribune once described them. Judge Patrick Murphy, who spent 26 years as Cook County’s public guardian before joining the bench in 2004, described the courts as “basically a medieval institution, where you have the king and vassal lords and the serfs. The king picks his lords and they run things. That’s a system that was set up by Richard J.”

It wasn’t long before Evans was picked to run things. His first assignment was in the domestic relations division, which handles divorce, child custody, and other family law issues. Case management had been a mess there for years. Instead of having trials on consecutive days, they were scheduled weeks or months apart. There was also discrimination against litigants tied up in child-support disputes. The court maintained separate and unequal facilities for married and unmarried parents, leading to a 1993 federal class-action lawsuit against the chief judge’s office for violations of the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Soon after taking office in 1994, Chief Judge Donald O’Connell appointed Evans to chair a committee tasked with making the division more efficient. The following year, O’Connell named Evans as the division’s presiding judge, praising his “outstanding” performance as a supervisor, his ability to work with attorneys and other judges, and the administrative experience he brought from his days on the City Council. The Chicago Bar Association applauded Evans’ elevation.

As presiding judge for the next five years, Evans oversaw major reforms: restructuring court calendars to fight judicial burnout, reorganizing the division to promote continuity in case handling, and expanding the division into the county’s five suburban courthouses so litigants and lawyers didn’t have to schlep to the Daley Center. He also led a panel to study racial and ethnic bias in the courts and extended job opportunities to people without political connections.

“As a young lawyer, I found the Cook County system to be a difficult one to navigate, rife with political and personal hierarchies and rivalries,” recalled Loyola University law school professor Lisa Jacobs, whose first job after law school was clerking for Evans. “Judge Evans assured me that if I did my work well and to the best of my ability, I did not need to have political patronage to keep my job or to be successful under his supervision. He was true to his word.”

The Chicago Sun-Times reported that the city’s divorce lawyers, who had initially been skeptical about Evans’ lack of judicial experience, described him as “the best presiding judge that Cook County’s Divorce Court has seen in years.”

In November 1998, Evans faced his first retention election with ringing approval from the city’s legal community. It seemed that he excelled as a court bureaucrat even more than he had as a ward boss. Far from calling him a has-been, the Tribune was advocating for him to become an Illinois Supreme Court justice. In the summer of 2000, O’Connell made Evans the head of the prestigious law division, citing his “significant experience” and “superior administrative skills.” Some suspected that Evans, now the highest-profile Black judge in the county, was being groomed for chief. O’Connell announced his resignation a year later.

On Sept.12, 2001, 251 circuit judges gathered on the 17th floor of the Daley Center — nervous to be in a skyscraper the day after the terrorist attacks — for the most contested chief judge’s election in the court’s history. The candidate lineup was reminiscent of a dad joke about Chicago’s ethnic makeup: It was Evans against three other candidates, one Italian, one Irish, and one Jewish. (A woman had initially joined the mix but ultimately withdrew.) After a record three rounds of voting, Evans emerged victorious.

If there were any lingering questions about whether the Daleys played a role in Evans’ ascent to chief judge, Cook County Commissioner John Daley — Richard M.’s brother — recently put them to rest at Evans’ last county budget hearing.

Reflecting warmly on their years of friendship and collaboration, Daley reminisced: “When you were elected as chief judge, I was part of that and tried to help you.”

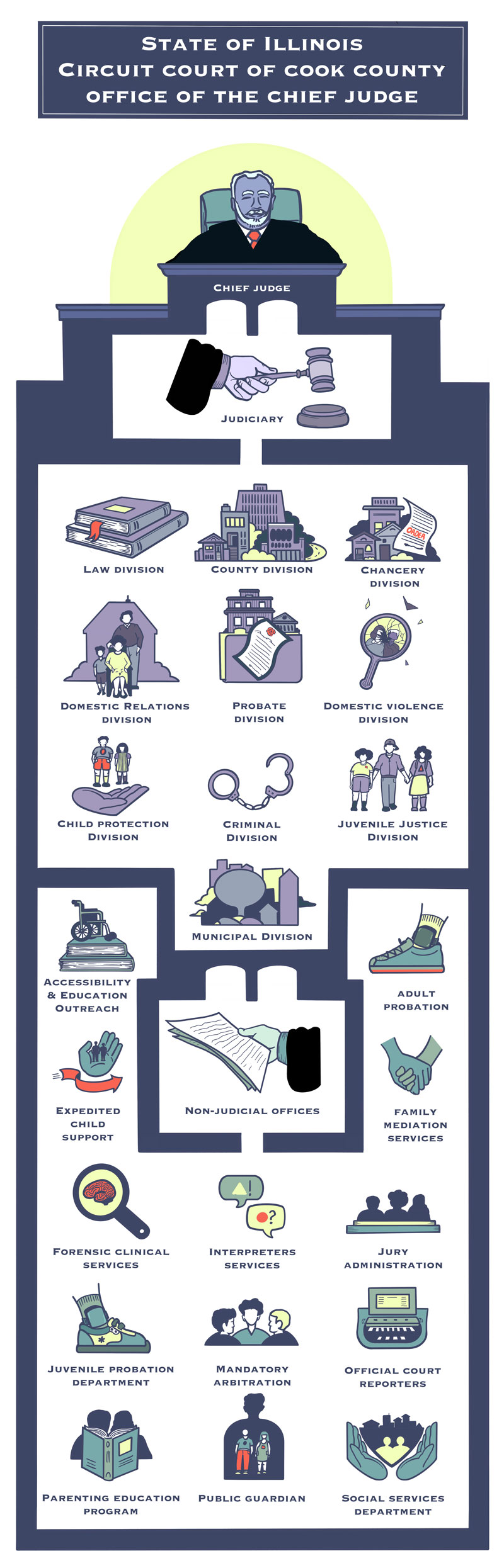

When Evans took over the court’s vast bureaucracy, several of the court’s present-day divisions and locations did not exist. Still, he was in charge of the system’s then-$187 million budget, 400 circuit and associate judges in a dozen courthouses, and an army of nonjudicial employees overseeing functions including child support, mediation, jury administration, court reporting, probation, and parenting education. The system handled 1.7 million newly filed cases every year — over a million more annually than it does today. “It was a steep learning curve in terms of the full panoramic view of what a chief judge does,” he recalled. As chief judge, Evans also had the power to appoint and chair the committee that reviewed applications for associate judges and created a short list of finalists for circuit judges to vote on. This gave him the ability to directly influence the makeup of the judiciary, which was then 70% male and 77% white.

His experience as a presiding judge helped him get a running start in the new role, but so did his background in ward politics. Although he had not previously worked with court employees from unfamiliar departments such as probation or social services, “I knew plenty of them,” he said. As alderman, he “could ask that certain people be appointed to be probation officers, or people be appointed to be clerks,” Evans said. “So I had personal relationships.”

O’Connell, his predecessor, had a dictatorial reputation; as Murphy described it, “If someone disagreed with him, they were transferred to cleaning washrooms.” (O’Connell did not respond to numerous requests for an interview.) Evans’ leadership style in this new role was lauded by some as thoughtful and considered, and criticized by others as hands-off and reactive. If as a presiding judge he had been seen as a decisive reformer, as chief he became famous for slow-moving government by consensus. He was always surrounded by people in “acting” positions. He avoided firing anyone if he could. He formed committees to examine problems, and sometimes committees to examine the recommendations of other committees. Unlike previous chief judges, he seemed willing to hear out critics and reformers.

“Comerford had no interest at all in meeting with us,” said Malcolm Rich, the former longtime executive director of the Chicago Council of Lawyers and founder of the Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts. “O’Connell would meet with us anytime, but it’s not like he was listening to anything we had to say.”

Hardly anyone who agreed to speak about Evans has seen the inner sanctum of his office on the 26th floor of the Daley Center. (A pandemic-era Zoom interview with Fox 32 once revealed a glimpse of a light-filled room cluttered with files, knickknacks, framed pictures, and a few winding houseplants.) Instead, meetings took place around a shiny, almond-shaped table in an adjacent conference room, under the watchful gaze of Evans’ three white predecessors in their official portraits, and more than a dozen photographs of his diverse array of presiding judges.

Attendees could expect to find Evans affable and demonstrating a remarkable recall of small details about their lives. He would then appear to listen attentively, taking copious handwritten notes on yellow legal pads. Meetings, however, would not usually result in any immediate action, several people said.

“You’ll talk to a lot of people who’ll say, ‘I thought I had a great meeting with Judge Evans, and then I walked out and thought about what transpired and realized he hasn’t committed to anything,’” Rich said. “He is the quintessential politician.”

I spent months talking to dozens of people about Evans — current and former judges, employees, personal acquaintances and political associates. Evans agreed to an interview just a few weeks before he was scheduled to leave office, after I made many direct requests, back-channeled with people close to him, and wrote him a long, pleading letter.

He invited me to his storied conference room, bringing along his top spokeswoman and, instead of a yellow legal pad, a seemingly empty brown accordion folder from which he eventually produced, for my consideration, an undated essay he had written for an Illinois Supreme Court newsletter. Although the interview was scheduled for two hours, we ended up talking for almost twice as long. During that time, Evans, dressed in a well-tailored gray suit and striped tie, sat relaxed in a soft leather chair at the head of the table. He took just one break and never opened his water bottle.

As he reflected on his tenure as chief judge, Evans was emphatic that he has never taken action because of pressure. He has always felt himself to be on the right side of history, and to hear him tell it, no one’s ever had to push him to do anything.

“Liberty, justice, fairness — all of that is uppermost in my mind,” Evans said. Maybe it was his gravitas or the fact that he’d grown up under Jim Crow and was inspired to become a lawyer by Thurgood Marshall, but he didn’t sound like a hack when he said it.

His first big opportunity to act on these ideals was in the battle for a new domestic violence courthouse. When Evans became a judge, he was initially assigned to the same 1920s-era furniture-warehouse-turned-courthouse at 13th Street and Michigan Avenue where some 55,000 domestic violence cases were heard every year. The Tribune described the quarters as “abysmal,” the very layout of which created a “hostile and unsafe” environment for litigants, often forcing abusers and survivors to share very tight spaces.

“Let’s say it’s a wife,” Evans recalled. “She would arrive at 13th and Michigan and get on that elevator, and the perpetrator, her husband, would get on that same small elevator with her, punch her right in the elevator, torment her right in that elevator.”

If prosecutors declined to press charges, meaning no criminal restraining order would be issued, Evans would watch from the window of his chambers as women waited for the bus to the Daley Center, to ask for civil restraining orders from an entirely different set of judges.

“And guess what the perpetrators did? When [the women] were standing on the street waiting to get a bus, they got attacked right there. And I could see that,” Evans said. “I saw them crying as they went into that building. I saw them crying as they came out of that building.”

Advocates had been calling for a better space for domestic violence cases since the 1980s. But closing the facility and opening a new one became a focus of Evans’ early years as chief judge. He favored a proposed site next to the Merchandise Mart, but it faced resistance from city business leaders and Mayor Richard M. Daley. “That’s a premier office building. It’s a great site along the river,” Daley said, calling the idea of turning a tax-generating property into a government building “silly.” Daley got his way when Cook County Board President John Stroger caved to pressure and a West Loop location was picked instead.

Evans stayed out of the fray as the conflict played out between Daley and the County Board; he said his priority was making sure the building was safe and convenient, wherever it was located. He got what he wanted in 2005, when the county finally opened a state-of-the-art, $62 million courthouse at 555 W. Harrison St. The airy building was designed with separate entrances and elevators for survivors and alleged abusers, on-site child care, and office space for advocates, legal aid, and social service providers.

The swanky new courthouse, however, did not address another persistent problem: domestic violence cases were still being heard by judges assigned to both civil and criminal divisions with no administrative communication between them, just as they had been when Evans first became a judge. Within three years of the ribbon-cutting, several high-profile murders of domestic violence victims and a sprawling Tribune investigation about low conviction rates in domestic violence cases elevated the issue in the public eye.

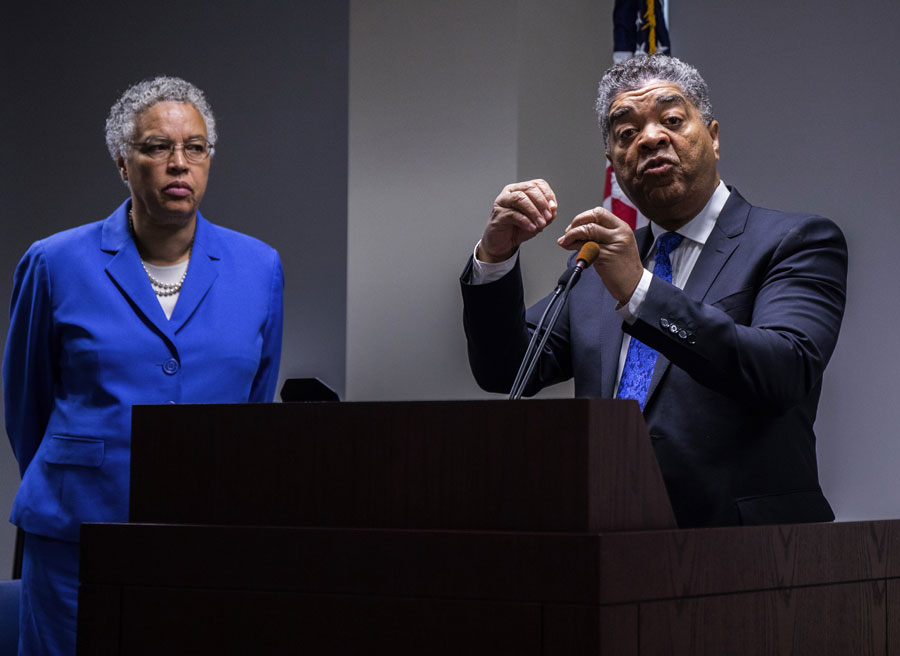

Evans tackled the problem, per usual, by pulling together a committee. “We worked really hard and gave a lot of suggestions, and he accepted almost all of them,” recalled retired judge Grace Dickler, who chaired it. “The most important one was that domestic violence should be its own division.” She became its first presiding judge in 2010.

Cook County’s current approach to domestic violence cases is unique in the country. “I couldn’t find another state that puts all domestic violence [issues] in the same division in the same courthouse,” said Elizabeth Monkus, a senior attorney at the Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts.

It hasn’t all been smooth sailing. At one point, Evans installed a presiding judge who was accused of creating an abusive atmosphere and limited access to court services. Periodically there’s news of abusers killing people who had been seeking help from the court. The court has also since expanded access to emergency petitions for restraining orders to nearly 24 hours a day. Though challenges in the division persist — it’s impossible to get basic data on how many restraining orders are requested and granted every year, and the courthouse is clogged with requests for no-contact orders arising from petty neighbor and family disputes — on balance, advocates have praised Evans for his efforts to improve court services for domestic violence survivors.

“It’s a sign of progress that we have a living, breathing courthouse that can respond to emerging needs of its client population,” said Amanda Pyron, CEO of The Network, a nonprofit that works with survivors of domestic violence. “The court has evolved to have a domestic violence division that is accountable to the community it serves.”

Evans was not just interested in making the courts more responsive to the needs of victims: His commitment to fairness was also reflected in his much more politically risky actions on behalf of people accused of crimes.

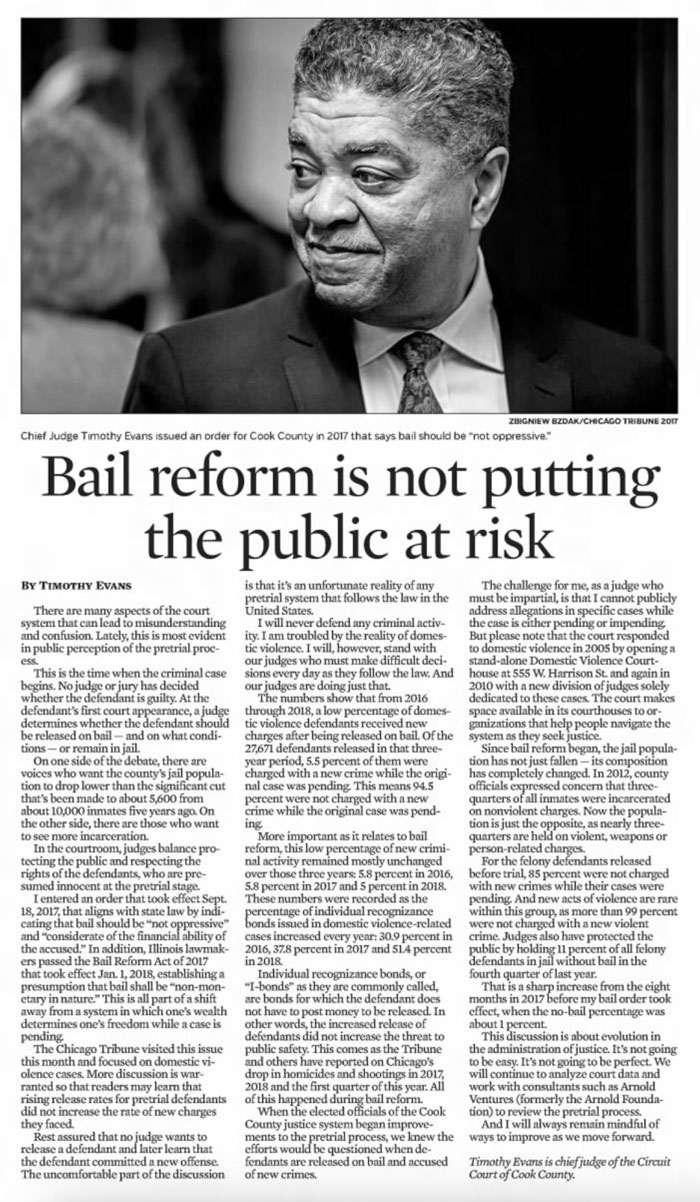

In 2017 he took a crucial first step toward the abolition of cash bail in Illinois. Many of the people I spoke to tell the story of how he got there as one about Evans deftly responding to pressure. But to Evans, it’s a story of destiny. In his version of the story, he’s not a leader who went through a profound transformation at a pivotal moment, but a righteous champion, slowly and methodically bending the arc of history toward justice.

Evans said bond court reforms became a priority as soon as he became chief judge in 2001. He had no experience in the criminal courts, so it came as a shock when he paid a visit to the area at 26th and California where recently arrested people waited for their bond hearings. Defendants, mostly people of color, were forced to sit on the floor, huddled together, and wait to appear in front of a video feed broadcast to an upstairs courtroom, where the judge, prosecutor, and defense attorney discussed their case.

“If you’ve ever seen the slave ships that came from Africa over to the Americas, to get everybody in the slave ships they didn’t put them in chairs. They put them on the floor,” Evans said. “That’s exactly the way it was when I became chief judge.”

During our recent conversation, Evans enumerated the actions he then took — the ones he saw as steppingstones to bond court reform — collapsing the years that passed between them into little more than commas. Outside forces did not factor into this story.

He described how he ended those problematic video bond hearings, but didn’t mention that it took him seven years to do so, or the civil rights lawsuit and damning university study that preceded his action. He talked about the pretrial services he implemented for defendants and the battles he fought with the county board to get them funded, but he made no mention of the Illinois Supreme Court investigation that gave him a playbook for those improvements. He touted how he’d set up the court with a philanthropically funded risk-assessment algorithm, but didn’t say anything about how little it ultimately changed. Even after these efforts and his order providing public defenders to people immediately upon arrest, bond court was fundamentally the same: a place where prosecutors had the upper hand while defendants were sped through hearings, sometimes humiliated, and often ordered to jail on bond amounts they could not afford to pay.

Meanwhile, societal attitudes toward incarceration were changing amid the Black Lives Matter movement and nationwide calls for reform set off by high-profile police killings of Black people. Conditions at the Cook County Jail and the time it took for cases to get to trial created immense pressure on people to plead guilty. Many incarcerated people also had mental illness or substance abuse disorders, leading Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart to launch a media blitz framing the jail as the largest mental health treatment site in America.

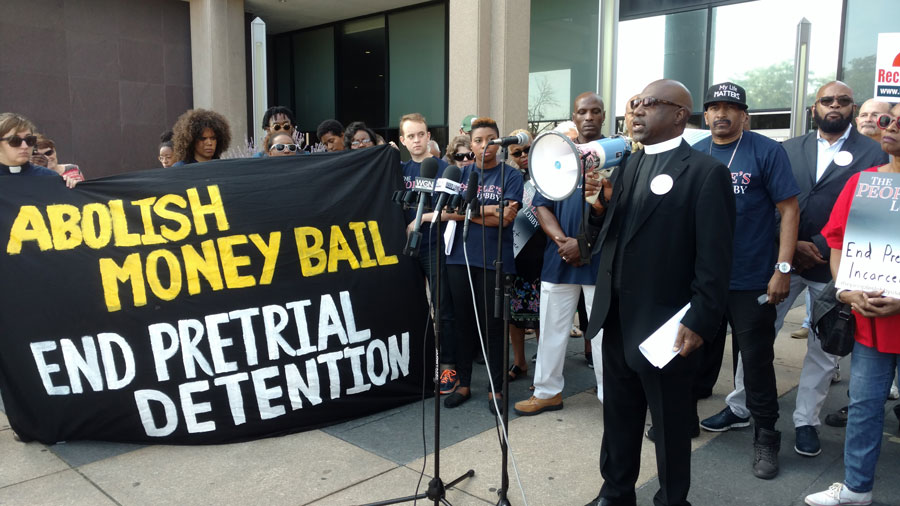

The progress Evans’ office was making wasn’t fast enough for advocates of money bond abolition, who viewed tweaks to bond court as inadequate. The problem, as they saw it, were the judges, who failed to consider “the financial ability of the accused” when setting bond amounts, as required by state law. In the fall of 2016, a group of civil rights lawyers filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of jailed defendants against Evans’ bond court judges. They claimed the way judges set money bail was unconstitutional. As the case proceeded, the pressure increased, boosted by demands for broader systemic reforms.

In the summer of 2017, Evans issued General Order 18.8A, which directed judges to consider defendants’ ability to pay when setting bond. Evans also created a new pretrial division, removing the judges who’d been assigned to bond court and bringing in a fresh crop.

“Was it all in response to pressure and organizing? Of course. But there were different ways someone in that role could have responded,” said Sharlyn Grace, who was then the senior policy analyst at the Appleseed Fund and a campaign coordinator for the Coalition to End Money Bond. “He did put in place a structure where better decisions were going to be made, and the law was going to be followed more.”

In our interview, Evans chuckled at the idea that any external factor pressured him to do anything. Yet for months before issuing the order, he had worked to identify the right judges to pilot its implementation, anticipating a politicized backlash and intense public scrutiny, according to Brendan Shiller, a criminal defense attorney who was active with the coalition and became a close adviser to Evans during this time.

“He was looking for a reset and folks he was confident would be logical and rational and not emotional under the heat that he knew would come,” Shiller said.

The heat came from the left and the right. Some new judges continued to set bond amounts with apparent disregard for people’s ability to pay, though advocates didn’t blame Evans for those decisions. On the other hand, there was intense media coverage of instances when people released on their own recognizance were rearrested on new violent criminal charges. Police and politicians, victim advocates, and even judges were critical of the policy changes and blamed Evans for endangering the community.

But Evans told me he was such a big believer in the reform that he was prepared to get voted out of office over it. He was ultimately vindicated by the data. A 2020 study published by Loyola University found the order successfully reduced the cost of bail and increased the number of people released pretrial. Meanwhile, the rate of people who were then rearrested on new violent criminal charges did not change, staying at 3%.

Most of the people I spoke with said Evans’ stance during this time paved the way for the 2023 Pretrial Fairness Act, which abolished money bail in Illinois. His order set the stage for the work that got done in Springfield, Preckwinkle said, because “we basically tried out the idea of not having cash bond in Cook County as a way of sort of piloting for the rest of the state [and] … there wasn’t a dramatic increase in crime.”

In the years since, Evans has become one of the law’s most vocal defenders, always returning the conversation to the data, and to the constitutional principle that every person is innocent unless proven guilty.

Hours after our interview, Evans spoke to a group of about 30 Loyola University law students at the request of his former law clerk, Lisa Jacobs, who now teaches there. Speaking extemporaneously (as he seems to do at every public appearance), Evans reviewed his proudest moments as chief judge, repeating some of what he’d just told me almost to a word. For comic relief, he occasionally acknowledged that I’d heard it all before.

During the Q&A, a student asked Evans to comment on arguments she’d heard against bond reform as a summer intern at the domestic violence courthouse. Some judges, she said, had told her that moving away from the old bail system meant abusers were no longer forced to have a “cooling-off time” in jail after being arrested.

“Those are all legitimate arguments,” Evans said. But he was emphatic: “Talk to a person who is innocent. You ask them if they need cooling-off time — if they need the kind of cooling-off time that caused them to lose their job, that would cause their whole family, while they’re locked up, to get evicted because nobody is paying the rent.”

The presumption of innocence was a concept that animated Evans throughout our conversation. He didn’t just bring it up in relation to bail reform. He said it was also core to how he dealt with employees and judges under fire.

For example: Last year, domestic violence division Judge Thomas Nowinski came under intense public scrutiny after a woman was killed by her husband. The man had been charged in prior domestic violence incidents in Nowinski’s court. Instead of detaining the man pretrial, the judge had ordered him to stay away from his wife and wear a GPS monitor. It was the second time in less than a year that an accused abuser with a case before Nowinski had killed a victim.

The calls for Evans to respond were deafening. Members of the public demanded Nowinski be removed. Members of the judiciary demanded Nowinski be defended. But in our interview, Evans said he handled the matter like a judge. The only thing that had mattered to him, he said, was the evidence.

“I read the newspapers every day,” Evans said. “But I can’t take any of that into consideration in the decision that I make.”

After reviewing the information available to Nowinski, Evans concluded the judge had made the best decisions he could, based on the law, with the information provided to him by prosecutors and other officials. Evans ultimately moved Nowinski out of the division at the judge’s request — Nowinski had received death threats, according to Evans — and reminded the public that he never made transfers because of a judge’s legal decisions. Evans suspended the GPS technician who had missed the husband violating his allowed boundaries without pay; the technician subsequently resigned.

Judith Rice, the presiding judge of the domestic violence division, said Evans’ way of doing things is better for the courts. “You make fewer mistakes when you do that,” she said, though she wasn’t commenting specifically on Nowinski. “Yes, at times, many of us wish that he would be faster to pull the trigger. But you know what? When he did pull the trigger, we didn’t have to have a do-over, because everything was considered.”

Yet Evans’ accounts of managing the courts with the unwavering impartiality of a judge belie plentiful evidence that he also managed them with the calculations of a politician. At times he rebuffed calls to interfere with judges’ controversial legal practices by pointing out that wasn’t his role. “I’m not the appellate court,” as he put it. In situations when judges were in the hot seat for ethical violations, he noted that the job of meting out discipline belonged to the state’s Judicial Inquiry Board. And when it came to scandals in the administrative arms of the court system, he leveraged time, deliberative processes, and his exemption from open-records laws, allowing news cycles to run their course.

Beginning in 2013, the Tribune uncovered problems in the Adult Probation Department, which oversees people sentenced to community-based supervision. The paper revealed the department had lost track of hundreds of probationers. The next year, the same reporters exposed a group of rogue probation officers who had for years worked secretly with the Chicago Police Department and the FBI to pressure probationers to become informants, and planted drugs on people who resisted. The unit also used curfew checks as a means to conduct warrantless searches of people who were not on probation but lived with someone who was.

It took Evans three months to demote the probation chief, whom he moved into an administrative job in his own office, and three years to fire the boss of the rogue unit. (Evans said the decision to fire the latter “required extensive investigation and analysis, as well as a degree of due process for the employee.”) In the meantime, he commissioned an outside law firm to investigate the department, and said he’d make the results of the inquiry public within 60 days. He never did, despite repeated shaming by the Tribune for breaking his promise. Some probation officers told the Tribune they believed “the investigation actually was aimed more at trying to uncover the newspaper’s sources than exposing wrongdoing.”

But even more than the probation department scandals, it’s Evans’ handling of the Juvenile Temporary Detention Center that has cast a shadow on his legacy. The center holds far fewer kids than it did when Evans took it over in 2008, yet allegations of children being abused and neglected by staff there have continued to surface. In 2018 The Chicago Reporter revealed a troubling overreliance on “room confinement” — the youth jail lingo for solitary confinement. In 2022, Evans’ “blue ribbon” committee on the detention center (the third such committee he had convened) called the facility “isolating and deprivational.” Its chair encouraged Evans to fire Superintendent Leonard Dixon. A class-action lawsuit recently filed by more than 300 plaintiffs details allegations of physical and sexual assault dating back to the early 1990s, with at least a fifth of the complaints alleging abuse since the chief judge’s office took over.

Evans has received no shortage of advice on how to improve conditions at the juvenile jail, much of it coming from committees he himself appointed. Yet he has implemented few of the recommended changes. He only released the 2022 blue ribbon committee’s report after it was leaked to Injustice Watch, and continuously resisted calls to replace Dixon. In September, Injustice Watch reported evidence suggesting Dixon might not live in Cook County, as he is required to; Evans hired outside lawyers to look into it and said they found that he did. (Evans declined to release the firm’s findings, citing his office’s attorney-client privilege.) He has proudly cited positive notes from recent outside reviews of the facility and brushed over the negative ones.

“Enough with the committees,” Eugene Griffin, the chair of the blue ribbon committee, wrote in a 2022 Sun-Times op-ed after learning Evans planned to create another committee to review his panel’s recommendations. “Needed changes to the care of detained youth can only be initiated by the chief judge. For years now, Evans has been saying that he wanted the JTDC to focus on the rehabilitation and healthy development of adolescents. Yet for years the JTDC has failed to do that.” Evans did not publicly respond, but the head of the union representing JTDC staff did. In a letter to the editor, she described the committee’s recommendations as “ill-informed and irresponsible policy prescriptions” that “besmirched the valuable work that the JTDC’s diligent and compassionate staff do every day.”

The union — one of 10 locals that represent Evans’ 2,500 employees across the court system — is crucial to understanding Evans’ inaction here. For years, county government has been moving slowly toward dismantling the detention center and transitioning most of the young people to smaller, community-based settings. Evans has publicly supported this idea. But sources involved in the decision-making said the fate of unionized detention center employees — a fifth of the court system’s workforce — has been a sticking point for Evans. Organizations that have the experience and willingness to take charge of the children may not be willing to take on Evans’ staff, they said. Yet the chief judge has told the unions that the transition away from the detention center “is not geared toward the elimination of their positions.”

In our conversation, Evans shared that his deliberative way of working is actually rooted in an experience with unions during the Harold Washington era. As Evans told it, after his election, Washington was eager to tackle the persistent problem of broken elevators in high-rise public housing buildings. Residents had to walk up and down many flights of stairs, and were sometimes assaulted on the way; a woman had died descending the stairs to get medical help. Washington wanted to fire all the old operators, whom he viewed as failing to maintain the elevators, and hire new people.

“Problem was, they were all in the same union,” Evans said. The people Washington wanted to hire wouldn’t cross the picket line. “So it was well-intentioned, but he didn’t check to see who would be affected by him firing the people whose job it was to repair the elevators.

“I never will forget it,” Evans said of what happened next. “The same people [who had to] walk those 10 flights of stairs still had to walk the 10 flights of stairs.” He said it taught him about the perils of quick decisions, even when they seem like the right ones. “I hope I never act too soon.”

The instinct not to act too quickly was also a political one, and he appeared to suffer his own consequences for breaking with it. The first challenge to his leadership of the court came in 2010, after a local TV news expose accused several judges of playing hookey. Evans reassigned them less than a week later. William Maddux, then the presiding judge of the law division and a onetime ally, mounted a campaign in which he criticized Evans for “throwing people under the bus.”

“To immediately declare a person guilty without even speaking with them is the kind of thing that is harmful to the morale of the judges,” Maddux told the press.

Even though Evans won the election decisively, and publicly chalked up Maddux’s run to an unrelated scuffle he’d had with law division judges, it seemed to be a cautionary tale. Over time, his approach to disciplining judges became so careful that he is now more often criticized for his inaction and leniency. While the chief judge does not have the authority to remove judges from the bench, he can reassign them to administrative duties — aka “judge jail” — and refer them to the state’s Judicial Inquiry Board. Evans leans on a committee of presiding judges to make such decisions.

“There are judges that don’t even live in the state, don’t come to work, abuse the sick time, never do a trial, and they’re never held accountable,” said Anna Demacopoulos, a recently retired judge.

Stephen Brandt, who retired last year after heading the court’s legal research division and was in Evans’ administrative inner circle, framed it differently.

People mistakenly assume Evans “has a lot more authority than he actually has,” Brandt said. But Evans is also keenly aware that he serves at the pleasure of his fellow judges.

“He’s gotta tread lightly sometimes in what he does, because if the judges who elect him don’t like it, they’ll vote for somebody else,” Brandt said. “You don’t have the kind of authority to make the kinds of improvements he wants to make unless he can get elected.”

The 2016 election was the only one in which Evans appeared to campaign as if he was truly threatened. His main challenger was Tom Allen, a white former alderman who had served on the City Council from 1993 until he was elected judge in 2010. He was assigned to the chancery division and was well-liked — “equally as nice” as Evans, as one election observer put it.

The summer before, Evans had faced rare public criticism from other judges. Patrick Murphy had sent out letters criticizing Evans for inadequately staffing courtrooms that serve primarily poor people and calling on him to relinquish control of the selection of associate judge finalists. In her retirement announcement, Judge Sherry Pethers asserted that Evans had politicized appointments, depriving her of an assignment in the law division where she’d spent her early career as a trial lawyer. She lamented seeing people she believed to be less qualified than her get the assignments she wanted, and how people always told her to go talk to Evans.

“He never once returned my calls,” she said in the letter. “I wrote. Never heard a word. Called to set up a meeting. Never got a call back. Being ‘nobody who nobody sent’ doesn’t cut it. And because of that, qualifications and experience don’t either.”

Both judges said their gripes weren’t meant as personal attacks on Evans, whom Murphy described as a “decent, caring and intelligent leader” and Pethers commended for his support of LGBTQ judges. But the issues they surfaced were flash points in the campaign and suggested a growing discontent among judges with Evans’ hands-off leadership and perceived culture of favoritism.

Then, weeks before the election, news broke that an attorney clerking under Evans, who had won a judicial primary, had been allowed by a judge in Markham to wear a robe and rule on a few traffic cases. Though Evans fired the lawyer and put the judge on administrative duties, Allen accused him of not acting fast enough and allowing the courts to become a “laughingstock.”

Days before the vote, influential power brokers in the Black political establishment, including a number of Black ministers and the not-yet-disgraced Ald. Carrie Austin, said publicly that the challenge to Evans was racially motivated. Evans won, 129-103.

His next challenger, Lorna Propes in 2019, ran on a platform of outrage about the growing scrutiny of judges by Injustice Watch and “special interest groups” like the Judicial Accountability PAC. But according to court insiders, she wasn’t strong in retail politics. She lost 143-102. No one bothered campaigning against Evans again until 2025.

When the court’s circuit judges gathered on the 17th floor of the Daley Center in September to vote for chief judge, only four had been on the bench as long as or longer than Evans. Just 15 were there when Evans was first elected chief. More than half had been judges for less than a decade. In other words, Evans’ electorate had changed; he could have been a grandfather to some.

Even if being an octogenarian didn’t bias people against him — there was no indication he was in poor health or suffered any mental deterioration — he still needed to work the voters, many of whom didn’t really know him. But to some, he seemed to abandon the basics of retail politics right as he needed them most, becoming vulnerable to the maneuvers of a better politician.

“In the past, when someone was running against him, he campaigned — went around and shook everyone’s hand,” said Murphy. “This time he didn’t.”

Charles Beach was focused on his ground game. He’d only been a judge for eight years, most of that time as an associate — he’d never even participated in an election for chief judge before. And though he was well-regarded in the legal community, he had no background in politics or government administration. Throughout the summer, Beach, 55, went to every courthouse in the county and met with almost every judge for a one-on-one conversation.

“This campaign is one in which people want to have a dialogue and have a conversation,” Beach said. “Talking to people directly is useful.”

People who know Beach spoke about his warm personality in the same glowing terms as they did about Evans’.

“Everybody loves Charlie,” said Julie Koehler, the head of the public defender’s homicide task force, who has known Beach since law school at DePaul University. “It never occurred to me that anyone could beat Evans, but if anyone could beat Evans, it would be Charlie.”

For the judges who didn’t have an established relationship with Evans, or political clout, or couldn’t get on his radar because they weren’t taking initiative in ways that aligned with his priorities, Beach’s promise of responsiveness and an open-door policy must have been alluring.

“I had dinner with a younger African American judge about a month before the election, and he said he was going to vote for Charlie Beach, and I thought, geez, Tim is in trouble,” said Murphy, 86. “He said, ‘Does Tim return your phone calls?’ I said, ‘Sometimes yes, sometimes no.’ I think there was a lot of ill feeling toward him among younger judges that he was out of touch with them.”

Evans denied that. “People who didn’t think I was working as hard as I had didn’t see how hard I was working,” he said.

As in his 1991 aldermanic race, Evans dismissed the possibility of losing reelection. “I don’t think that you’ll have to worry about that,” he told me days before the vote. “I don’t spend much time trying to figure out what will happen if I lose.” And why would he? He’d been running for office for 52 years, 27 times in all, and he’d only ever lost twice.

He lost to Beach 144-109. Evans admitted he hadn’t seen it coming.

“I had done what I thought needed to be done, to show how effective we were, to show that my experience was superior,” he said.

With his usual politesse, Evans hinted that Beach might have no idea what the job will take. It surprised him, he said, that Beach and his other challenger, Nichole Patton, had even decided to run. Neither had yet served a full six-year term as circuit judge. The faintest note of bitterness broke through his genteel demeanor as he reflected on his relationship with the two judges: “I helped them to get where they were. Both of them were in the law division. That’s a coveted position, and I had helped both of them to get to the law division.”

That attachment to the transactional ways of old Chicago politics may also help explain Evans’ loss. The election results suggest the courts are no longer full of judges who have a habit of trading electoral loyalty for career advancement.

Since his win, Beach has spent the last 2½ months forming transition teams and committees and trying to understand the complexity of the court bureaucracy he is inheriting. It is a larger court than the one Evans took over, with a larger budget, more divisions, more courthouses, and an entire new arm of administrative duties. It is also a far more diverse court: Since 2001, the number of women judges increased by 71% and the number of nonwhite judges by 76%. Evans was also praised for improving LGBTQ representation in the judiciary.

Beach also inherits a court that is better in its customer service operations than the one Evans took over — more efficient in some divisions, more responsive to the needs of unrepresented litigants, and with well-established remote offerings. But plenty of challenges remain, chief among them the county’s beleaguered electronic monitoring program and the juvenile detention center. Dixon submitted his resignation the day I interviewed Evans, following a series of stories by Injustice Watch about alleged abuses at the youth jail. In response, Beach said he “welcomed the opportunity” to appoint a new administrator to run it.

There are also many bureaucratic mysteries for Beach to address: Why does every division of the court have a different approach to electronic recordkeeping? Why does the head of forensic clinical services make $430,000, more than anyone else in the court system? Why is the Daley Center mostly a ghost town in the afternoons? Why has the regular publication of many court program statistics not resumed since the pandemic?

Beach will be in a position to provide answers, if he so chooses, but the chief judge’s powers are still exercised with virtually no public accountability, at the pleasure of hundreds of independently elected officials. The judicial branch still isn’t subject to Illinois’ Freedom of Information Act. There is no inspector general’s office with authority to investigate the courts. The state’s Judicial Inquiry Board is woefully understaffed and almost never disciplines judges. The Cook County court system remains a sprawling, feudalistic empire where change can happen at a geological pace — or at warp speed, depending on the political calculations of its leader.

As for Evans, he has no plans to retire. With three years left in his sixth term as a circuit judge, he is entitled to return to the courtroom. He’s secured one for himself on the top floor of the Daley Center, where he plans to continue to work with the Restorative Justice Community Court program, the creation of which is among his proudest accomplishments. The program serves people ages 18 to 26 who have been charged with certain nonviolent crimes. Their charges are dropped if they admit to the crimes and work to repair the harm with their communities. According to Evans’ office, graduates had a 13% recidivism rate one year after completing the program, compared with 65% in a control group. These courts have admitted fewer than 700 people in eight years — a rounding error compared with the tens of thousands who become criminal defendants in Cook County every year — and have been criticized for falling short of ideal restorative justice practices. But Evans is a true believer in the program. When he talks about it, he sounds like he’s on the stump.

Evans was one of the last of his generation and brand of politicians still in power. And unlike so many of his peers — Ed Burke and Michael Madigan, most recently — the end of his reign is not coming in a fall from grace. The biblical reference he made in 1991 comes from Ecclesiastes, a book that says we are always at the mercy of time and chance. It also reminds us of the wisdom of accepting things as they are, not being quick to anger, and valuing relationships. Evans’ public life, by all accounts, has mostly been a manifestation of its lessons.

Tim Evans doesn’t seem to have any enemies, and even some of his critics concede he did a pretty good job as chief judge. Evans probably could not have achieved what he did in a term or two; as a former presiding judge put it, changing things in Cook County’s courts is like “turning around an ocean liner.” His proudest accomplishments were possible because he kept getting reelected, and for 24 years, he kept enough judges happy.

What Evans lost in respect from those who have found him too slow to act, too permissive, too superficial, he gained in the admiration and friendship of many others. And more importantly he gained in time, which gave him the chances he needed to make some things happen.

In our conversation, Evans sounded as if he would be content to spend the remainder of his public life leveraging his political skills to advance ideas he believes in. He said it’s a part of his destiny. But he may be biding his time, planning, once again, to endure. After all, the next election for chief judge is only three years away.

Injustice Watch reporter Kelly Garcia contributed reporting.