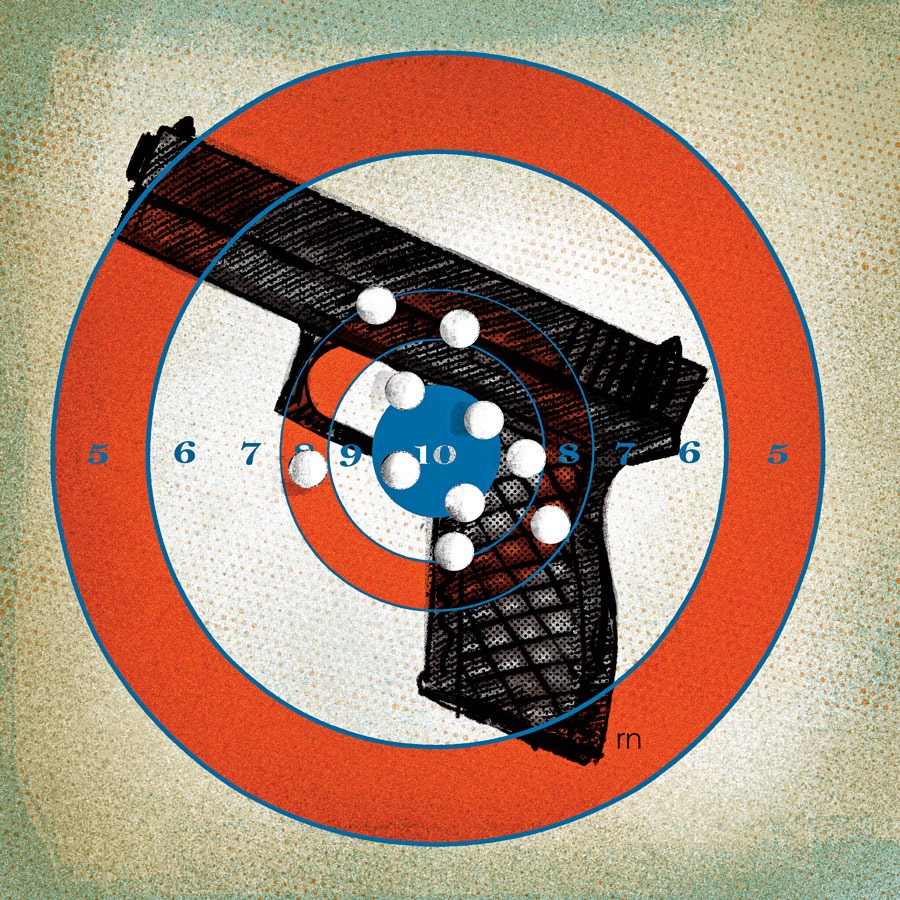

Around 2 a.m. one night in the summer of 2022, five friends walked out of a club in the Loop and got into an argument with a man who then pulled a gun. He fired a Glock pistol at them, one that had been illicitly converted into an automatic weapon capable of unleashing 20 rounds every second. A witness in a nearby apartment said the spray of bullets sounded like fireworks. Two people were killed — shot in the head and chest. Three others were hit but survived.

Mass shootings like this are too common in Chicago, but now they could become less frequent, thanks to legal pressure the city has applied to Glock. In 2024, the city sued the Austria-based gunmaker and its U.S. subsidiary, accusing them of knowingly producing and marketing handguns that could readily be transformed into illegal machine guns. All it took to make the change was a cheap add-on known as a Glock switch, which could be ordered online or 3D-printed. According to the city, in the three years leading up to the suit, the Chicago Police Department recovered 1,300 of these modified Glocks.

In October, the gunmaker relented. After failing to persuade a judge to dismiss Chicago’s suit, Glock announced that it would stop all production and sales of its easily adapted pistols. It was a major victory for the city — and for its law department’s affirmative litigation division, which brought the suit.

Municipal law departments usually represent a city when it’s a defendant in civil cases. But of the 250 attorneys Chicago employs, seven make up the affirmative litigation division, which operates like a tiny public interest law firm within city governments; they safeguard the rights of local consumers, workers, and tenants by suing companies or entire industries to make them change behaviors and pay steep restitution. “We are trying to use affirmative litigation to protect our residents and hold bad actors accountable,” says Stephen Kane, the division’s head.

These were the lawyers behind the city’s suing of Juul Labs for marketing its e-cigarettes to kids, adding to the legal pressure that forced the company in 2023 to stop the practice and pay Chicago $23.8 million to go toward public health. The division was also behind the city’s 2022 settlement with Uber Eats and Postmates, in which the food delivery services paid $10 million after being accused of “deceptive and unfair practices,” like fees above caps. The city has even taken on Hyundai and Kia, accusing them of making their cars easier to steal by failing to install industry-standard antitheft technology; property management firms for roping in tenants with duplicitous rent-to-own contracts that often resulted in evictions; and some of the world’s largest oil and gas corporations for allegedly lying about their part in causing climate change.

— Stephen Kane, head of Chicago’s affirmative litigation division

“We are trying to use affirmative litigation to protect our residents and hold bad actors accountable.”

In total since 2023, the city has secured more than $90 million in restitution and civil penalties from those it has sued. “This division is probably one of my most impactful in terms of the day-to-day life of citizens,” says Mary Richardson-Lowry, who as Chicago’s corporation counsel is in charge of the city’s entire legal team.

Chicago started its affirmative litigation division in 2018, with four full-time attorneys. The Trump administration was then — as now — attempting to withhold federal funding over Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance, and attorneys who regularly defended the city in lawsuits suddenly had to go into plaintiff mode and take the federal government to court. At the time, Chicago was also engaged in a lawsuit against Equifax, over a data breach, and in ongoing opioid litigation that would eventually mean $78 million from a national settlement to be paid out over 18 years.

This kind of city-led plaintiff-side impact litigation reflects a shift in culture at municipal legal offices. In 2006, San Francisco became the first city in the nation to form a dedicated affirmative litigation unit — just after it sued California to strike down a ban on same-sex marriage — and Kathleen Morris was put in charge of it. She managed a dozen attorneys, at first getting only 10 percent of their time. They sought out cases that personal injury lawyers, nonprofits, state’s attorneys, and the Justice Department wouldn’t or couldn’t take on. “There are civil laws that are going unenforced because no one has the incentive to enforce them,” says Morris, now a law professor. “It’s not perfect law enforcement. But it helps to rehabilitate people’s view of whether government is on their side.” The nonprofit Public Rights Project has since led the effort to spread affirmative litigation units to a few dozen other cities — including New York, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Oakland — and train some 250 local government attorneys.

This year, Chicago’s affirmative litigation attorneys have helped the city file seven lawsuits against the second Trump administration and joined numerous third-party cases, managing to stop the withholding of hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funding to the city. The unit has been pressed into triage on multiple fronts. With the federal government abdicating enforcement of many of its own regulations and consumer protections, and with a Justice Department steered away from civil rights work, cities are being compelled by necessity to step into the breach. “This is a division absolutely built for this moment and the onslaught of work coming their way,” says Richardson-Lowry. To handle that increasing workload, she hopes to bump up the number of affirmative litigation attorneys in the next year to 11, if the city can come up with the money.

Chicago’s lawsuit against Glock was the first to test Illinois’s 2023 Firearms Industry Responsibility Act, which attempts to outmaneuver a 20-year-old federal law that mostly indemnified gunmakers from civil liability. Linda Mullenix, a mass tort expert and the author of Outgunned No More, sees Chicago’s suit against Glock as a major development in a legal “revolution” that started in 2019, when the civil action against Remington Arms after the 2012 Sandy Hook killings was allowed to proceed. She says the Chicago case could rewrite how gun companies do business in this country. “It’s a snowball effect,” Mullenix says. “Eventually, the entire industry is going to come to the table and say, ‘Let’s settle this out.’ That’s what happened with tobacco.”

Although Glock has stopped making the modifiable pistols, Chicago’s affirmative litigation team isn’t done with its lawsuit. The city is still seeking financial penalties against the company for the multiplied harm these weapons caused.