I live north of Howard, that little notch of Rogers Park that sticks up above the rest of the city. This chimney of Chicago is the perfect place to observe the disappearance of the middle class in Chicago. When I walk out my front door, I see poverty: There’s a tent city in Triangle Park. The homeless under the Howard L viaduct, trying to keep warm and dry. On Mondays and Wednesdays, the hungry line up for free food at the Howard Area Community Center, and every day, they sit down to a free lunch at A Just Harvest. At least once a day, I’m asked for spare change. A panhandler once followed me into the post office. Another followed me into a Subway, until she was yelled at by the employee, who had seen this bid for cadging a free meal. There’s a man in kneepads who stands in front of a Caribbean bakery chanting, “Dollar? Dollar?” as though it’s his life’s fixation.

That’s only one side of the neighborhood, though. On Juneway Terrace, just around the corner from all this desperation, the tall, deep-porched houses are worth — on average — $800,000. You won’t find a working family’s bungalow north of Howard. The neighborhood hairstylist charges $75 for a cut. It may be unusual to find wealth and penury existing so close together, but to me, it says a lot about the trajectories of the rich and poor in Chicago.

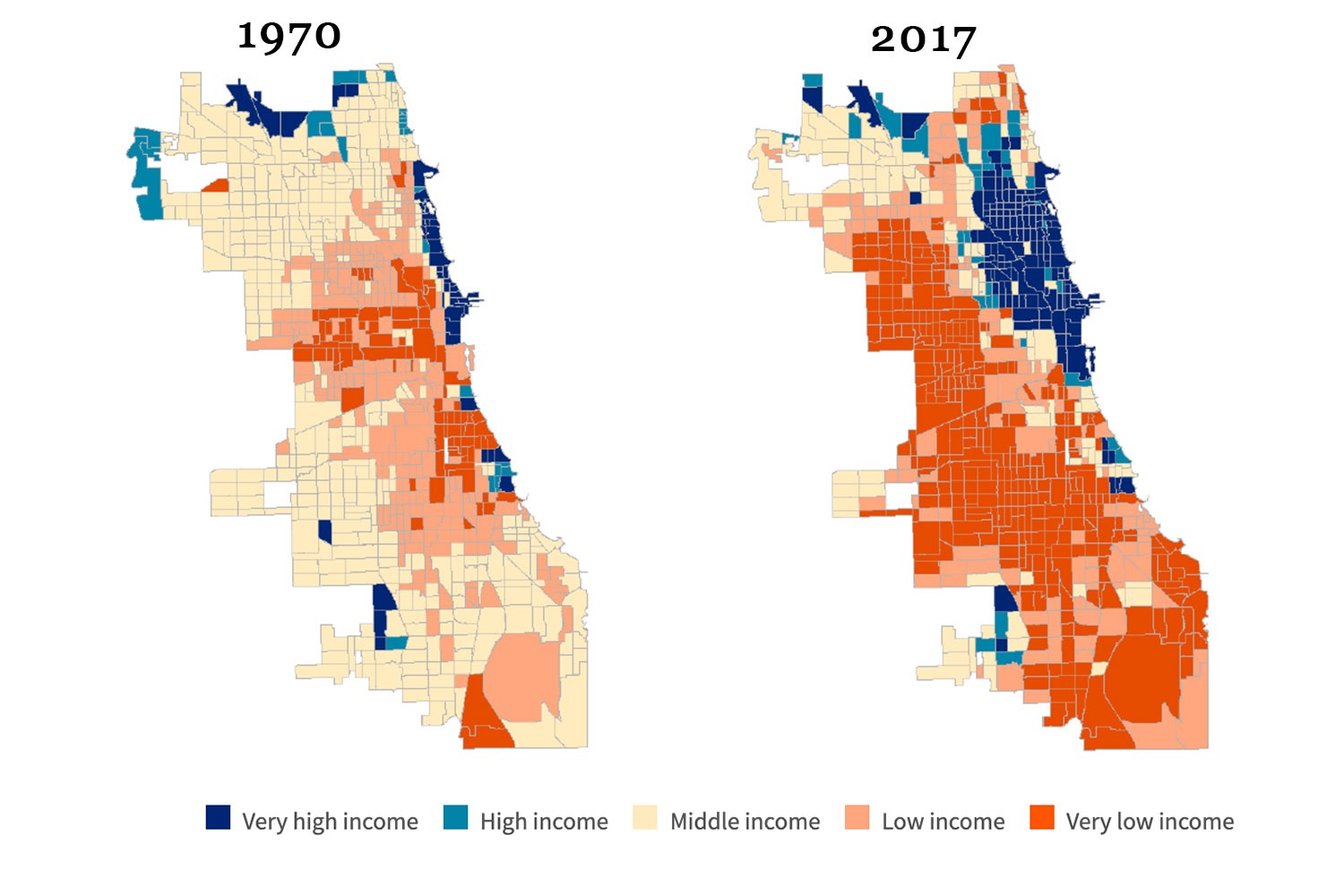

There’s a map that, like so many other Chicago maps, charts the decline of the middle class in the city. In 1970, nearly half of the city’s census tract were identified as middle income. Now, the few middle-class neighborhoods left are in the Northwest and Southwest corners of the city, where city workers with middle-income jobs — teachers, firefighters, nurses — tend to cluster. The South and West sides are almost all lower income. And there’s a new element: high-income neighborhoods, which have expanded from a thin strip along the lakefront in 1970 to consume almost the entire North Side today. According to the Pew Research Center, the nation’s share of middle-income families has declined from 61 percent to 51 percent over those years. The middle-class squeeze seems even more pronounced in Chicago.

“The middle class is declining because the top 10 percent is swelling” in the city, says demographer Rob Paral, “and the bottom 20 percent is swelling. In a place like North Center, the median income is going through the roof.”

That’s part of a nationwide trend. In the same time period displayed by those maps, the share of income earned by the top 10 percent has increased from 33 percent to nearly 50 percent, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Increasingly, those high earners want to live in cities, which is a big change from the 1970s and ’80s, when people with money were fleeing urban America for suburban America. Since 2000, the fastest-growing concentration of $200,000-plus earning households is on the former site of the Cabrini-Green housing projects, which has replaced blight with condominiums, gyms, movie theaters and a Mariano’s. The city’s fastest-growing neighborhoods are also its wealthiest. The Loop, with a median household income of $119,837, has nearly doubled in population since 2010. Meanwhile, the population of Edison Park, one of the few remaining middle class neighborhoods, has been completely flat. Englewood, one of the city’s poorest, has lost half its population since 2000. The city isn’t building middle class housing, as it did during the era of bungalows and two-flats. It’s building the Aqua Tower, it’s building the St. Regis, and it’s building affordable housing. In 2025, the city invested $137 million in affordable housing and opened 561 affordable units.

Last year, 156 homes sold in the Chicago area for more than $4 million, beating the previous record of 136. More than half were in the city.

“It’s been a good year for the rich, but not so much for the middle class,” Daryl Fairweather, chief economist at Redfin, told Crain’s Chicago Business.

Even worse for the middle class, the Chicago area has the fastest-rising home prices in the nation: up 5.83% in October 2025 from a year earlier. So where is the middle class? It’s leaving the city, or in some cases, the state.

“The sense I have, the Black folks moving away from Chicago, they’re not moving to Texas, they’re moving to Indiana,” Paral says. “They can buy a house there.”

In Lincoln Square, there’s a three-bedroom house selling for $1,099,000. In Buffalo Grove, there’s a four-bedroom house on sale for $425,000. At those prices, who can blame a middle-class family for leaving the city?

North of Howard may be an anomaly, in that it’s unusual to find the rich and poor living in such close proximity. You won’t find panhandlers and soup kitchens in the Gold Coast. Nor will you find million-dollar houses in North Lawndale. It only takes a short drive through the city to see both, though. It’s a half hour drive from State and Division to Central Park and Ogden, an hour by bus. As America races toward extremes of rich and poor, Chicago is racing even faster.