Hip-hop poets Idris Goodwin and Kevin Coval are taking the mic at Yale and at Steppenwolf-and, along the way, attempting to change your definition of rap culture.

|

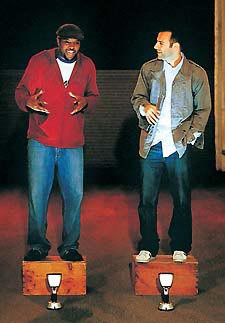

Photograph: Lisa Predko |

| Idris Goodwin and Kevin Coval drop a few beats under the Metra tracks in River West. |

Idris Goodwin is sensitive to the fact that he works in a medium that most Americans think of as über-sexed, highly blinged, and often violent. But comparing big-business hip-hop to Goodwin’s community of artists is like “McDonald’s versus the family-owned diner on the corner,” says the 28-year-old, who strings together phrases like “Who got the big-gest verbs / Who got the biggest words / It’s a one-legged race to see who’s the biggest nerd.”

His roommate, Kevin Coval, chimes in: “Hip-hop is the most democratic culture since jazz, probably more so, because all you need is the pen and paper.”

Part of a growing movement that crosses lines of spoken word, rap, and theatre, Coval and Goodwin could be the hardest-working people on the city’s hip-hop scene. Earlier this year, Coval, 31, released a book and CD of spoken word poetry called Slingshots and has been touring the country since to support it. Goodwin recently released a self-titled album.

Each, however, seems to draw the most inspiration from the other: since 2003, they’ve been collaborating on a two-man performance called Know What I Mean, a mix of intellectual rap and spoken word that they are recording as an album this summer. In July, the duo will perform excerpts at Yale and other stops along the East Coast. In August, they’ll take the stage alongside veteran bluesman Billy Branch at Steppenwolf Theatre’s “Blues/Hip-Hop Intersection,” an evening that explores Chicago’s blues tradition and its influence on popular culture. Other performers include poet/singer Avery R. Young and MCs Sense and Butta.

Simply asking Coval and Goodwin how long they’ve known each other can spark a lively discussion: “Three years.” “No, more.” “Four?” They finally settle upon 2002, when they met through a mutual friend. In conversation, the two roommates mimic the call-and-response format they use to perform; they also speak fondly of one another’s influence. “Kevin’s taught me a lot,” Goodwin says, praising Coval’s level of focus. “When Idris and I just kind of kibbitz,” Coval says, hands moving in the space between them, “there’s so much humor there.”

Coval has had to cross no few lines since his Jewish childhood growing up in Northbrook; many of his solo pieces turn on a Hebrew phrase, or refer to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Goodwin grew up “the only black kid” in the Detroit suburb of Rochester Hills; he says he was drawn to rap in part because “these guys looked like me.” He eventually developed an interest in the art form’s deep roots in traditional American blues and jazz, an evolution he shares with other aspiring poet-musicians and playwrights at Young Chicago Authors, where he and Coval both teach. “Popular culture is never a good representative of [the tradition] it takes from,” says Goodwin. He smiles. “Like Garth Brooks is not indicative of old bluegrass music.”

INFO: Coval and Goodwin perform in “Blues/Hip-Hop Intersection” on August 7th at Steppenwolf Theatre, 1650 N. Halsted St.; 312-335-1650.