Largely forgotten now, Myrtle Reed dazzled as a best-selling romance novelist and Chicago socialite 100 years ago. But in her personal life, a happy ending proved sadly elusive

It started with an old book at a yard sale, a book I judged, frankly, by its cover: mauve with a gilt art nouveau floral design. The book was Lavender and Old Lace by Myrtle Reed, copyright 1902. Turn-of-the-century romance, Edwardian chick lit. I figured I'd never read the thing, but it was attractive, and the price was a buck.

Illustration: Lisel Ashlock |

| Reed's books had an almost mystical genesis, springing forth from just a title. |

At home, I spread the covers, fanned the pages, and caught a folded brown newspaper clipping as it fell loose:

Author A Suicide, Puts Blame Upon "Model Husband"

Myrtle Reed, Who Wrote "Lavender and Old Lace,"

Takes Poison Dose

Even a century out, the story caught my eye. Reed, a Chicagoan, was one of America's best-known authors in the first decade of the 20th century. She and her husband, a real-estate man named James Sydney McCullough, were leading boldface personalities, known for the parties they hosted at "Paradise Flat," their Kenmore Avenue apartment. On their fourth wedding anniversary, October 22, 1910, the couple threw a dinner for a dozen fashionable couples at which the women present evaluated the men to select Chicago's "model husband." McCullough was declared the winner.

Less than ten months later, on August 17, 1911, Reed wrote a note to her maid:

My Dear Annie-I am leaving you a check for $1,000 for your true and faithful service during four years. If my husband had been as good and kind to me and as considerate as you, I would not be going where I am. -Mrs. Mac

Then, a month short of her 37th birthday, Myrtle Reed swallowed far too much sleeping powder, lay down in her bed, and died.

It was an irresistible story. And so, aided by dozens of contemporary newspaper and magazine accounts, commentaries by those who knew her, court papers, and Reed's own books and letters, I made a journey into a shaded corner of Chicago society at the turn of the last century.

Elizabeth Armstrong Reed, Myrtle's mother, married at 18 but was a self-taught scholar who wrote respected books on Hindu and Persian literature. Her husband, Hiram, cobbled together a living as-among other things-a Campbellite preacher and the founder of the Midwest's first literary magazine, Lakeside Monthly.

As a child growing up with two older brothers in Norwood Park and later the Near West Side, Myrtle-who had been born on September 27, 1874-was more than chubby. Neighborhood boys taunted her so viciously that she mostly stayed indoors, reading and writing. While still a pupil at William H. Brown elementary school, she published a story in a juvenile magazine. "I must have been born with a pen in one hand and a sheet of paper in the other, howling for ink," she later said. At West Division (later McKinley) High School, she edited and contributed poems and stories to The Voice, the student monthly. But a magazine editor and a teacher discouraged her from pursuing a writing career-a painful insult that she did not forget.

The girl's childhood intensity grew into what friends described as a breakdown in her teens-the reason, they said, she never attended college. She could be deeply serious, talking literature and philosophy for hours, but she also had a prankish side. In high school, she began a correspondence with a fellow high-school editor in Toronto, James Sydney McCullough. He asked for a photo; ever sensitive about her weight, she sent a head shot. He asked for a lock of hair; she sent a few reddish curls from her Scotch collie. He replied that he had always favored auburn hair. Intrigued and flattered, Reed kept up the exchange for years, but avoided meeting the Canadian in person.

After her 1893 graduation, still at home with her parents, Reed composed stories, articles, and poems and sent them around for publication. Her first acceptance came in 1896. The following year, she later boasted, she had 23 bylines in print.

Then, one afternoon on a streetcar, a title came into her head: Love Letters of a Musician. By the time she reached home, the five words had blossomed into a plan for a book containing a year's worth of unsent letters from a violinist to the object of his dreams. Scarcely leaving her typewriter, she completed her first book in five days. After a local publisher rejected the manuscript, she sent it to McCullough, who encouraged her. Later that year, she arranged for the publication of a limited edition of 900 copies bound in suede; the edition sold out in ten weeks. In March 1899, she found the book and herself a home with G. P. Putnam's Sons, a long-established New York publisher. "I have just signed a contract for ten years," she wrote to a friend. "I keep my copyright and get a ten per cent royalty on every copy sold. Not bad, is it?" Putnam's had bet well: Love Letters, which came out in the fall, was a hit.

Reed spent part of that summer, before her publishing breakthrough, in New York. McCullough offered to meet her there, and she accepted, but when he arrived for a week's stay it took him until the last day to find the courage to follow through. They had a two-hour face-to-face before he had to catch his train back to Toronto.

Either Reed's weight didn't put him off or he found her literary and financial promise attractive enough, for it wasn't long before McCullough moved to Chicago. He started brokering small real-estate deals; she took to signing notes to her girlfriends "Myrtle Reed, spinster pro tem." It had been six years before they first saw each other. It was to be seven more before they married.

|

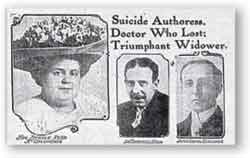

| A Chicago Tribune article from 1912 depicts the author, Myrtle Reed; her duplicitous doctor, Edmund Sugg; and her less-than-perfect husband, James Sydney McCullough. |

During the first years of the century, Reed settled on her writing technique, which was not very different from the pattern that produced her first book: an almost mystical beginning-just a title-followed by a long percolation and then a burst of fevered writing. "My mind works like a geyser," she said. "Simmers and seethes for a long period, then explodes." She could time the explosions. For her yearly romances, she shut herself away each February and March and produced a manuscript for her publisher's birthday, April 2nd. Other works she fit in during the year.

Even in her day, critics derided her novels as old-fashioned and saccharine, but Reed was a stunning commercial success, both in her romances and in a series of ten cookbooks (containing 1,000 recipes each) written under the pen name Olive Green. She was in the rare league of authors whose works typically sold 100,000 copies or more. Quickly, she had money and, it followed, social position.

By 1905, Reed and McCullough decided, at last, to marry. Reed, who was real-estate savvy in her own right, bought a lot in the just-developing Lincoln Park neighborhood, at 2281 Kenmore Avenue (in what is now the DePaul University campus). She and McCullough built a three-story apartment building, named it "The Maple Leaf," and kept a six-room top-floor flat for themselves. They planned a December 1906 wedding, but, fearful of publicity, they advanced the date to October 22nd and slipped off across the lake to Grand Haven, Michigan, where they were quietly married in St. John's Episcopal Church.

McCullough could rarely get anywhere on time, so when he didn't show up at Dearborn Station for their wedding trip, Reed, hardly surprised, left without him. He caught up with her 12 hours later, explaining that he had been having his shoes shined. His tardiness would only get worse, and become one of the chief issues in their relationship, even if always treated-at least in public-with humor.

Reed and her man (she called him "Binkie," after a dog in a Rudyard Kipling tale) settled in at the new apartment, which they adorned with a lot of brass and mission oak, Navajo rugs, and a wall lined with early rejection slips. They called the place Paradise Flat and threw dinner parties for a select circle of authors, lawyers, doctors, and bankers. The gatherings often featured inventive interactive entertainment and were well covered in the society pages. There was an annual Husband Show, in which the men competed at sewing a button, harnessing a corset, and guessing the price of a hat. There was a feast in honor of the American hen-each invitation was written on a hard-boiled egg and delivered in a basket of hay and feathers. The official Paradise Flat toast, delivered to the clink of a silver cup donated by Reed's publisher, was the Irish standby: "May our house always be too small to hold all our friends."

Bits of Reed's novels reflected what was happening in her life-details of her wedding ceremony, for example, or a newly acquired cat. If her friends noticed as her works grew a little darker, they kept silent. But Reed had discovered that Binkie was less than the men in her novels, and that no matter how hard she tried, she couldn't mold him as she molded characters at her typewriter.

Nor was McCullough content. Reed's moodiness and exaggerated responses to his shortcomings were draining him. He was drinking, and he began to be absent more and more. Although he kept an office in the Hartford Building on South Dearborn Street, the more gin rickeys he downed, the fewer real-estate deals he orchestrated. Neighbors heard loud arguments.

In 1909, Reed, complaining of insomnia, checked herself in for a stay at a Winnetka health resort that specialized in the treatment of nervous diseases. There she met an intern, an Englishman named Edmund Sugg, who soon moved to Chicago, obtained a medical license, and began treating her. He prescribed Veronal, an early barbiturate used as a sleeping aid, and they consulted almost daily by telephone. He visited several times a week and the pair rode up and down Sheridan Road and Evanston Avenue in her electric runabout-so that he could observe her in real life, he said, rather than in his office.

Meanwhile, the McCulloughs moved up Kenmore Avenue to number 5120, one of the first apartment houses built at the start of the Uptown residential boom. She bought the building and took a third-floor front apartment. Considering what was going on in their marriage, they shouldn't have installed the entry sign "Paradise Flat" from the old place. But the masquerade had to continue-at least in public. In 1910, Reed dedicated a new collection of poems to her husband, but quietly took away his control of the building and her other real-estate holdings, turning things over to a management firm.

In August 1911, she inscribed the flyleaf of an advance copy of her final book, A Weaver of Dreams: "To my dear husband, who has it in his power to make all of my dreams come true. With love." In the book, a character asks whether it's possible to change a person. "Always," comes the reply. "If one is strong enough." In her real life, Reed was deciding that she lacked the strength, an admission she had made only to her mother and to Sugg, now her closest confidant.

As she drove her electric car around Uptown during her final days, on a page of the little notebook she always carried was the title of her next work, never to be completed: A Cobweb in the Grass. The plot involved divorce. No doubt, the characters would have rejected that path, for divorce, to Reed, was always unacceptable.

|

The World According to Myrtle In her novels, speeches, and letters, and in a collection of humorous musings called The Spinster Book, Myrtle Reed turned out witty observations with the skill of an op-ed columnist or a standup comedian. A sampling: "Have you ever seen a man carry a burden when there were a woman's shoulders near enough to shift the burden to?" "Man is like a luscious but doubtful edible, the mushroom. You have to marry him to test him. If you die, he's a toadstool; if you live, he's a mushroom." "Marriage appears to be somewhat like a grape. People swallow a great deal of indifferent good for the sake of the lurking bit of sweetness and never know until it is too late whether the venture was wise." "A woman marries in the hope of having a lover and discovers, too late, that she merely has a boarder who is most difficult to please." "Three things I have longed to see-the sea serpent, a white rhinoceros and an unselfish man." "A woman wants a man to love her in the way she loves him; a man wants a woman to love him in the way he loves her, and because the thing is impossible, neither is satisfied." "Penetrate deeply into the secret existence of anyone about you, even of the man or woman whom you count happiest, and you will come upon things they spend all their efforts to hide. Fair as the exterior may be, if you go in, you will find bare places, heaps of rubbish that can never be taken away, cold hearths, desolate altars, and windows veiled with cobwebs." –D. C. |

The events surrounding the suicide were thoroughly reported by the newspapers: how McCullough was expected home to celebrate the 12th anniversary of the couple's first meeting; how he came in drunk at 1 a.m., after she had gone to sleep, and left before she awoke; how Annie, the maid, returned at 9:30 p.m. from her usual Thursday off to find the flat dark, a note with a $1,000 check on her bureau, and a half-empty bottle of Veronal by her mistress's bed.

The press chronicled the suicide, the funeral and cremation at Graceland Cemetery, and the ensuing estate warfare in tabloid-like detail. "There was a salacious quality to the coverage of death in those days," says Jeffrey Adler, a University of Florida historian and criminologist who has studied Chicago murders and suicides. "Even more voyeuristic than today." Louis Liebovich, a journalism professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, explains why: "It was an era before our heroes were movie stars and baseball players. Rich, successful people were Americans' heroes. Chicago was exploding with immigrants, and someone like Myrtle Reed was everything they wanted to be."

In her will, written a year after they married, Reed left most of her property to her husband and lifetime cash payments to him and her parents. Down the line, after their deaths, McCullough's three sisters and eight Chicago charities would benefit. Her two brothers and their wives and children were specifically disinherited.

Settling the estate involved a series of lengthy battles. Reed's parents charged McCullough with mismanagement. He countersued to recover bank accounts jointly held with her mother and, later, for royalties from a book Elizabeth had published from a compilation of Myrtle's writings. Sugg submitted a bill for an average of 13 hours a week of services over two years. McCullough fired back by hiring a detective agency, whose investigation revealed that the "bachelor" doctor had an ex-wife, a son, a current wife he had deserted after three weeks, and, as a capper, a Milwaukee heiress he had promised to marry and almost bilked out of $10,000 before she caught on.

In the end, McCullough did all right. He had to cede some of the cash to his mother-in-law, but he got to keep thousands more, ane he recovered checks Reed had sent to others the day she died. Sugg's bill was disallowed. McCullough sold movie rights to several Reed novels for $50,000 (a few stories did make it to the silent screen).

In 1919, despite his hefty inheritance, McCullough came under state investigation for a deal described as an oil scam. I lost his trail after that. I located several grandchildren of one of Reed's brothers. They knew the basic outline of her story but no more; they didn't recall that her name had ever come up at family gatherings. One member of this generation, a nursing supervisor in the Midwest, paused to consider her great-aunt's creative spurts and the emotional state that led to her destruction. "Today," she said with a sigh, "we have diagnoses and medication for that."

As for the novels that once sold in the six figures, they're as neglected as their author. On the day I bought my attractive copy of Lavender and Old Lace, it probably hadn't been opened since 1911. Today, on the pages that had sheltered the browned clipping for all those decades, there remains a souvenir: a ghostly rust-colored footprint.