"Some people just don’t belong.” That was our unspoken credo. It also happened to be the tagline for Caddyshack, a movie that felt uncannily like our lives. Except we weren’t caddies. We pitied the caddies. They had to be polite to members and dress like them too. We wore concert T-shirts with the sleeves cut off, boasting farmer’s tans of unsurpassed starkness and definition. We smoked weed on the job and tore around in three-wheeled Cushmans that leaked oil and had empty beer cans rattling around in the back. We got paid minimum wage. We were invisible to the golfers. We were the people who didn’t belong.

We were the grounds crew.

That none of us were injured or killed during those baked suburban summers at the Aurora Country Club still astounds me, more than 30 years later. Well, none of us got killed at least. There was the time Jon — my best friend, who’d recommended me for the job — got hit in the head by a drive while mowing a fairway. The impact knocked him out cold, and the Toro mower he was riding scalped a wide swath through the rough until it ran into a tree and he came to, Walkman headphones still clapped to his ears. When we got Jon back to the garage, the grounds superintendent — a leathery ex–marine named Hans who had a pair of dice tattooed on his arm — took him in a headlock, inspected the welt on his forehead, and announced through teeth clenching a Pall Mall, “It was a Titleist!”

That same summer, Jon and I flipped one of the Cushmans into a bunker. We were thrown clear, but the two barrels of grass seed we’d been hauling spilled into the sand. Powered by a strength born of fear and adrenaline, we righted the cart, bent the steering wheel back into alignment, and began furiously raking the seed into the sand. This seemed a good strategy, as grass seed and sand are pretty much the same color. By some stroke of divine providence, the seed never sprouted.

Another time, our friend Vince, a hard-partying gearhead just out of high school, took a sheet of plywood to the shins when it flew out from under the tires of a pickup truck we were trying to free from the mud. Cretinous 17-year-old that I was, I could summon no better response to the sight of Vince writhing on the dew-covered grass than asking, “Do you want me to get Hans?”

A cardinal perk of the job, in our estimation, was that we got to operate lots of motorized things: chainsaws, big rotor mowers, rake-dragging Sand Pros, Yamaha four-wheelers, tractors, a small dump truck. I even got to drive a front-end loader once, with Jon and two other buddies riding in the bucket. We went down a hill, and the whole machine started to tip forward. My passengers jumped out in a panic, and the loader thudded back down on its rear wheels, center of gravity restored. The guys decided to walk the rest of the way to whatever pile of earth we were moving that day.

The grounds crew consisted of two subgroups: the summer hires and the lifers. The lifers, older than the rest of us by a couple of decades at least, ambled through their days at an unhurried pace. While I lurched toward the end of what I considered a single chapter of my existence, the lifers, for better or worse, had made a book of it. One was a potbellied mechanic and dedicated midlife pothead called Bubba. Bubba unreservedly owned his nickname, referring to his wife as his “old lady” and speaking in a sleepy vestigial Southern drawl. He remains the only person I’ve encountered in real life who actually used a rope as a belt. He spent much of his time crouched over engines, and dropping a penny into his exposed butt crack was a near-daily rite. The obligatory response when confronted by Bubba was to raise your palms and say, “Hey, I gave at the orifice.”

Another lifer was a garrulous drunk named Dave, a charity-case military buddy of Hans’s whose breakfast consisted of a four-pack of tallboys and who on Monday mornings would regale us with tales of romantic conquests that had surely never happened, bragging over and over again about a common sex act that, in a curious gesture of prudery, he referred to only as a “BJ Thomas.” As a condition of his sinecure, Dave was given the foulest tasks, the most memorable of which was disposing of a human turd that had been deposited in the No. 9 cup by an anonymous overnight trespasser.

Busting chops was the order of the day. The younger among us were given vaguely demeaning nicknames. I was El Flaco (“the skinny one,” a label bestowed by a Mexican-born guy on the crew). Jon was the Nose, due to the size of his proboscis. The more seasoned summer hires had earned the right to be referred to, in the accepted mode of straight male bonding, by their last names, or shortened versions thereof: Papo, Azem, and so on.

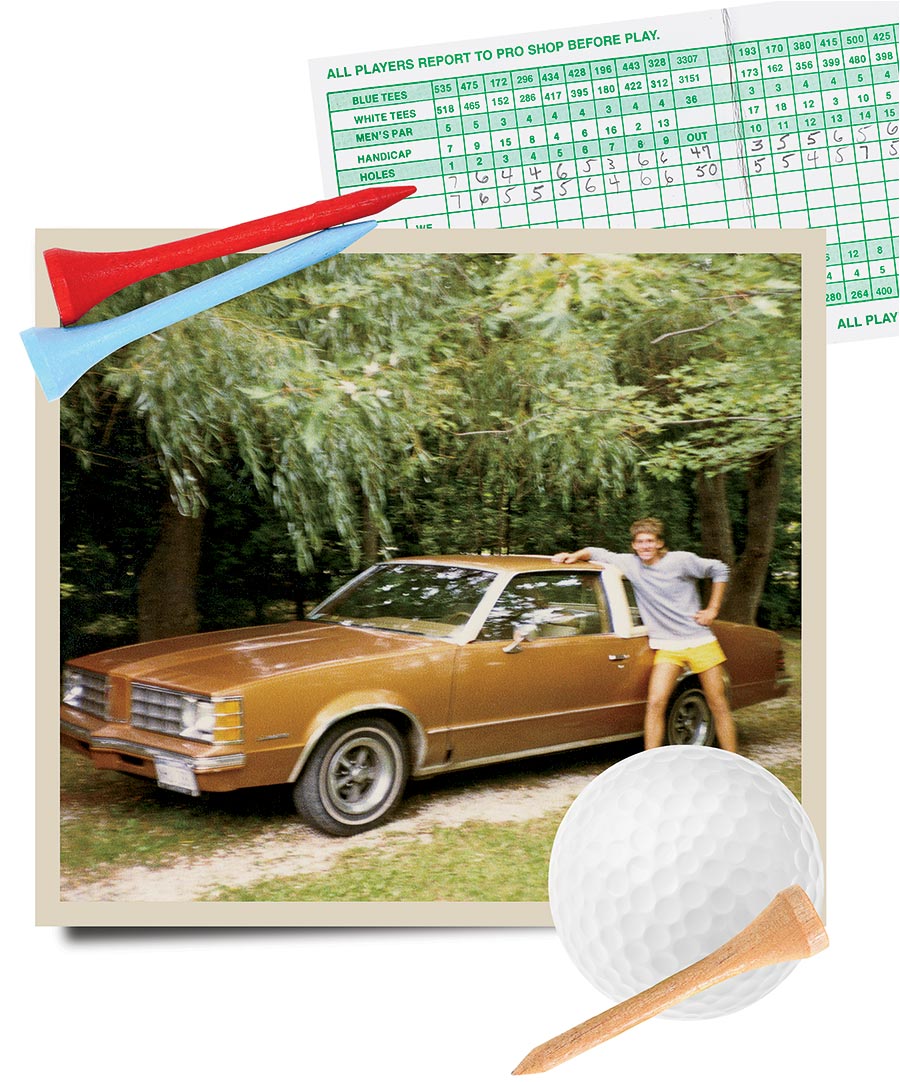

Our days were long (we started at 6 a.m., even on weekends) and (near-death experiences notwithstanding) filled with tedium. Like any group that spends a great deal of time together in an intellectual vacuum, we got on each other’s nerves. I remember actually coming to blows with Jon on a blazing July afternoon, but I’ve long since forgotten what we were fighting about. Hours later, in any case, we’d resumed our summer evening ritual of driving to the cornfields at the edge of town — suburban Chicago’s western frontier — and reclining on the hood of my rusted 1978 LeMans with a six-pack between us.

And yet for all the boredom and drudgery, the job engendered an easy camaraderie that’s hard to come by in an office these days. It even delivered small moments of sublimity. If you’ve never walked barefoot down a bentgrass fairway under the late-August sun with your pleasantly stoned friends, tossing handfuls of grass seed into divots, then you’ve missed out on a pretty restorative pastoral ritual. And there was something similarly gratifying about the backbreaking work of laying wet sod at the start of the summer, watering it day after day, and watching it take, transforming a brown tract of earth into something soft and green.

It was our job, after all, to make things grow. So what if it was for the benefit of guys in kelly green who threw their clubs at the caddies when a ball sliced into the rough.