Drivers crossing the Mississippi River eastbound on I-55 are greeted by this billboard: “Welcome to Illinois, where you can get a safe, legal abortion.”

The billboard is an advertisement for the Hope Clinic for Women in Granite City, but it also recognizes that the Mississippi divides two states that are moving in opposite directions on abortion. Missouri recently passed a “heartbeat bill,” which bans abortion after a fetus is eight weeks old, and only a court order prevented the state from closing its last clinic, in St. Louis.

Meanwhile, in Illinois, Governor J.B. Pritzker signed the Reproductive Health Act, which establishes abortion as a “fundamental right” and declares that a “fertilized egg, embryo, or fetus does not have independent rights under the laws of this state.” The new law codifies abortion rights previously protected only by court rulings; it allows late-term procedures if the fetus is not viable or the mother’s health is endangered; and it requires all health insurance policies issued in Illinois to cover the procedure.

Both states were responding to President Donald Trump’s appointment of two conservative Supreme Court justices believed to favor overturning Roe v. Wade. Because such a repeal would return jurisdiction to individual states, Illinois would become an island of abortion rights in the Midwest, surrounded by states likely to ban the practice altogether. Across the Ohio River, Kentucky also passed a heartbeat bill. Across the Wabash, Indiana tried to ban abortions motivated by a fetus’s sex, race, or disability, but the law was overturned.

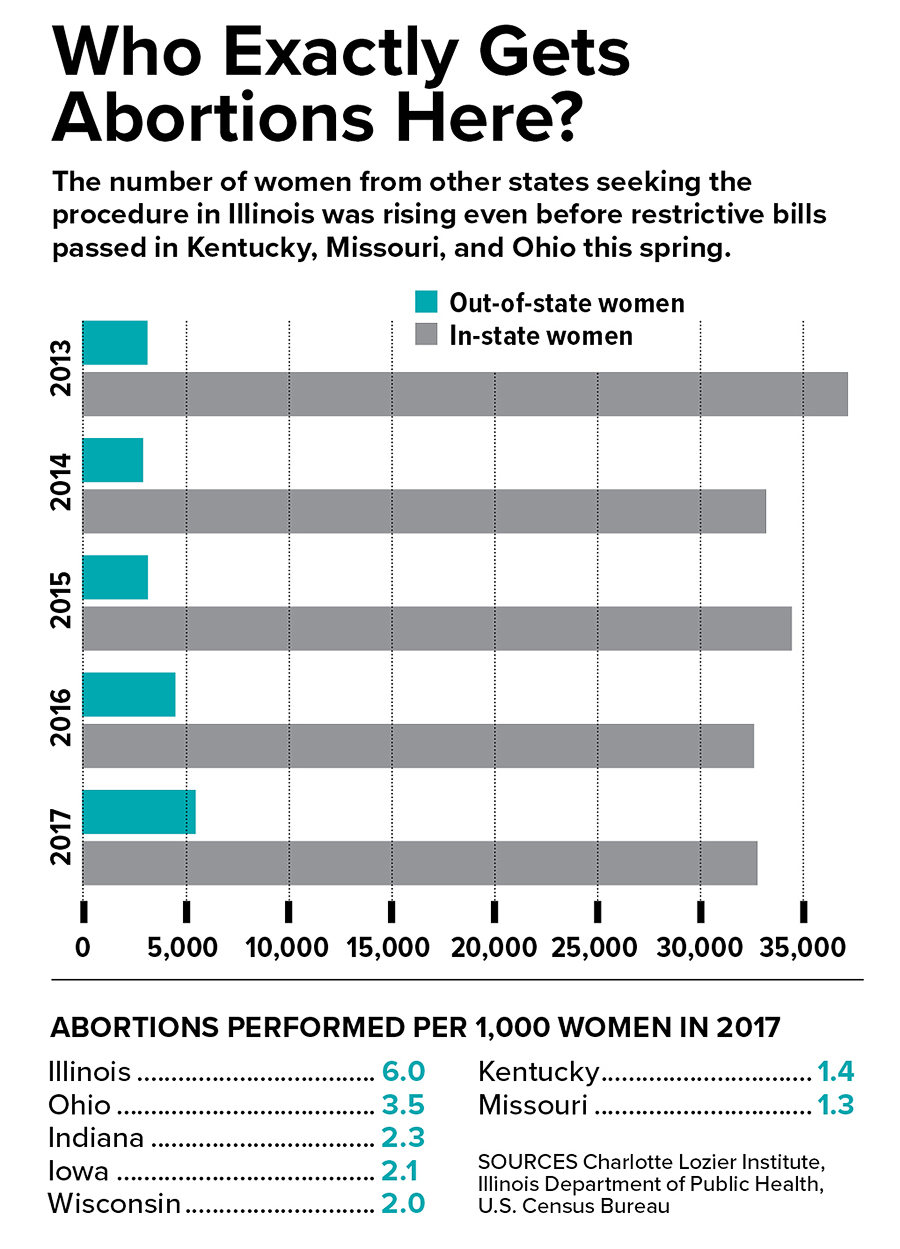

Already, 5,500 women a year travel to Illinois for abortions. (The Hope Clinic gets over half of its patients from Missouri.) That figure would surely increase. So could the cultural divide between Illinois and its neighbors, which for decades has caused young professionals to flee their conservative hometowns for Chicago. “We needed to build a firewall around Illinois to protect abortion rights,” says Representative Kelly Cassidy, a Chicago Democrat who sponsored the Reproductive Health Act. “I know that we already see women coming in from other states. It stands to reason we will see more.”

To Peter Breen, vice president and senior counsel of the Thomas More Society, an antiabortion law firm, that’s exactly what’s wrong with the new law. He believes it “wipes away … obstacles to performing postviability abortions in Illinois” because there are no criminal penalties for it. Breen is a former Republican state representative who lost his DuPage County seat in last year’s Democratic sweep of the suburbs. (His successor, Terra Costa Howard, voted in favor of the act.) “Once we start allowing third-trimester abortions, there will not be another state anywhere in the middle of the country that has abortion laws like ours,” he says. “If we decide to become the Wild West of abortion, people are going to fly in here from all over the country. That is not what we want our state to be known for.”

The Thomas More Society is considering a challenge to the provision of the act requiring insurers to cover abortions. That, Breen believes, violates the rights of employers opposed to abortion and would force them to choose between their religious convictions and offering health care coverage — “a terrible place to put small-business owners and small churches.”

Some of those employers will likely challenge the insurance provision, based on such precedents as the Supreme Court’s Burwell v. Hobby Lobby decision, which allowed a business to refuse contraceptive coverage, says Carolyn Shapiro, a former Illinois solicitor general. As for Breen’s Wild West analogy, Shapiro says abortion opponents are “trying to equate the real-world tragedy of a woman carrying a fetus that will die shortly after birth — or for whom continuing the pregnancy poses serious health risks — with a hypothetical woman at the end of a normal pregnancy who’s decided she doesn’t want to have a baby after all.” The statute does not allow a healthy woman to terminate a healthy pregnancy at that point.

As the Reproductive Health Act was debated, it sparked a culture clash between its Chicago-area supporters and legislators who represent rural communities. Before the bill was passed, a downstate clergyman delivered an invocation asking God to “judge Illinois for the sanctioned destruction of the innocent unborn.” Says that pastor, Cory Musgrave of New Beginnings Church in Fairfield: “As a whole, people in our area are very opposed to abortion. I think some of it has to do with the difference between rural and urban mindsets. Sometimes in smaller communities, you have tighter-knit relationships, and value life.”

As abortion debates consume legislatures around the country, the issue has come to be seen as emblematic of a state’s views on women’s rights. The New York Post reported on Manhattan high schoolers who crossed Oberlin College and Washington University off their lists because of restrictive bills that passed in Ohio and Missouri. Those students wouldn’t cross off Northwestern or Knox. “Not just with regards to the Reproductive Health Act, it really speaks to how we want to be perceived as a state,” says Cassidy.

Abortion is dividing the country more than at any time in the nearly half century since Roe v. Wade — and it’s shoring up Illinois’s reputation as the bluest state between the coasts.