Nick Kokonas has an uncanny ability to find an unexpected solution to an illogical situation. This talent enabled him to thrive as a financial trader, and then, despite no industry experience, to cocreate one of the world’s best restaurants and launch a tech company that’s been a game-changer in how dining reservations are made. But it can also rub people the wrong way. At home, for instance.

Dagmara Kokonas, his wife of 24 years, had grown tired of umbrellas going AWOL from their usual spots by the front and back doors. This was Nick’s fault. So Dagmara did what spouses do: She told her husband to quit losing umbrellas.

And Nick did what Nick does: He went on the website Alibaba, found a great deal on compact blue umbrellas, and bought boxes and boxes of them — 288 umbrellas in all. Then he placed one in every spot that Dagmara or their two sons might hope to find an umbrella, and he stashed the remaining boxes in the basement and at Alinea’s storage facility. When he sees that an umbrella is missing, he replaces it with another, so Dagmara never knows how many the family has gone through.

To Nick, he’d solved the problem. He made sure no one in his household would ever lack for an umbrella, and he got Dagmara off his back. But Dagmara didn’t want Nick to solve the problem. She wanted him to quit losing umbrellas. “We have a responsibility to our things and our home and our umbrellas, right?” she says.

“She’s right. You shouldn’t lose umbrellas,” Nick says with an exaggerated sigh. “But I have other, higher-priority things I like to spend my time worrying about than where I put the last umbrella.”

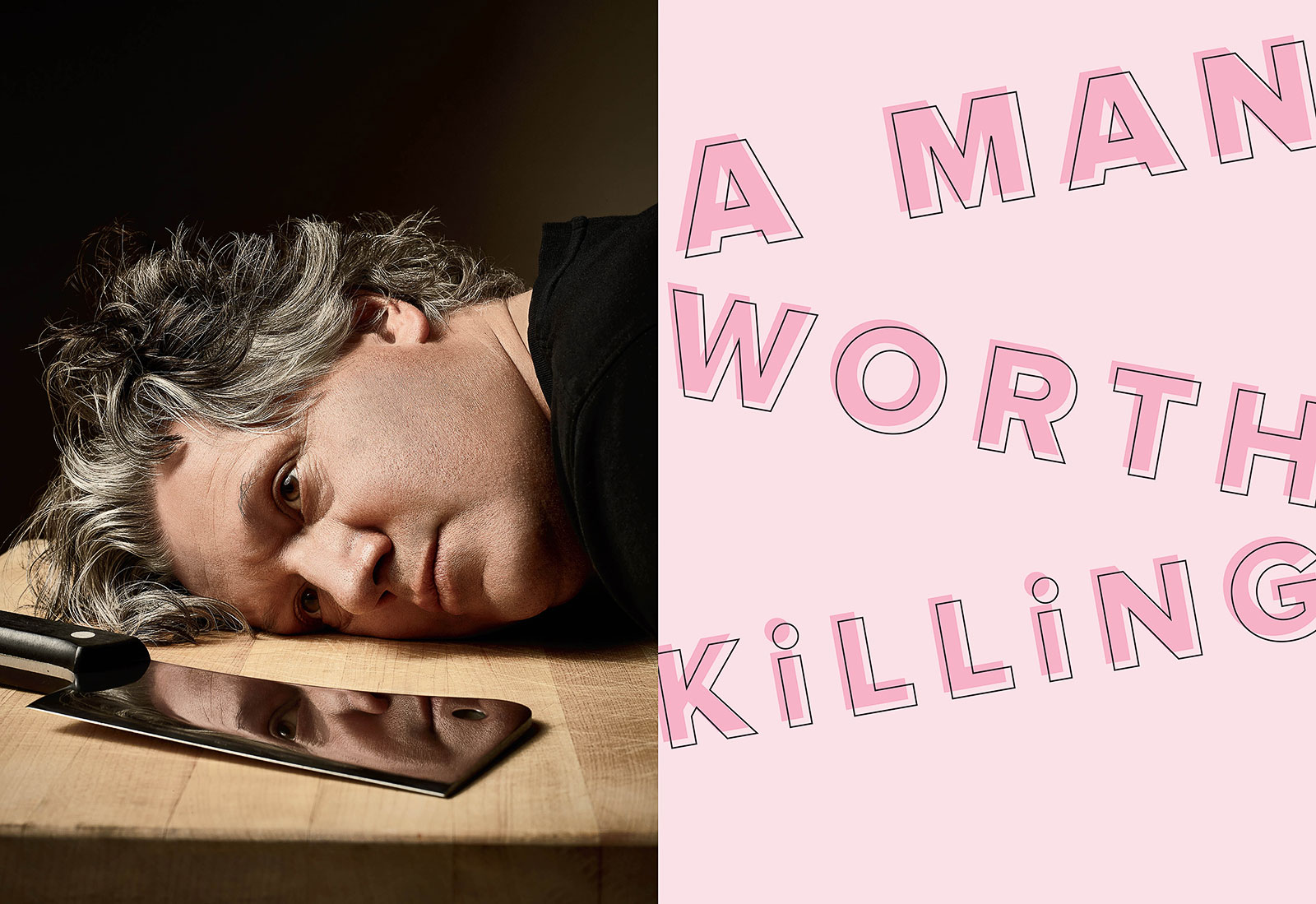

Kokonas, a youthful 51 with tousled graying hair and a casual ease about him, has accumulated much to worry about. He’s co-owner and cofounder of the Alinea Group, the company that he and star chef Grant Achatz have built atop the foundation of their wildly creative, internationally acclaimed restaurant Alinea. He’s also the CEO of Tock, a dining reservations system he launched in 2014 that has raised $18 million in funding and has a client list of 2,000-and-counting restaurants and wineries in 24 countries.

From the Alinea Group’s spacious open office in a converted West Loop factory, he oversees it all — about 120 employees onsite and close to 400 in total. His big-windowed corner office has such a close-up view of passing Metra and Amtrak trains that he and the conductors wave to each other. The white walls are bare, other than some whiteboard notes from a previous meeting. On an end table sits a compact blue umbrella.

This is the first time he’s ever had an office, he says, dismissing it as “a prison of my own construction.” So he is constantly in motion: He stops by people’s desks and pets their dogs, pulls up a stool for a quick lunch from the buffet laid out every day gratis so employees don’t have to waste time going out to eat, slips into one meeting, then another. Kokonas also spends time at the restaurants: Alinea, for which he and Achatz oversaw a nearly $2 million redesign that wrapped up in 2016, despite its already having earned three Michelin stars; Next, the West Loop rotating-concept restaurant that opened in 2011 concurrent with the Aviary, the fanciful bar next door (which spawned a New York outpost in 2017); and Roister, an open-kitchen-with-a-hearth concept on the other side of Next (with the newly opened St. Clair Supper Club in the basement).

There’s always work to do no matter the time or day. Around 7 a.m. Easter Sunday, Kokonas was typing out a lengthy answer to a client’s highly technical question about the Tock system; Kokonas had noticed the query and figured he could handle it quicker than the company’s help line.

But also, sometimes he’s unable to help himself, particularly when social media is involved. Like on that Saturday night in early March when he was out to dinner and got word that something was going horribly wrong with a certain celebrity chef’s visit to Alinea.

It was 5:16 p.m. on March 2, and Cat Cora of Iron Chef America fame was standing in the foyer of Alinea, demanding to be seated. But the restaurant had expected her the previous night, and now the general manager was telling her no tables were available. Cora grew heated, and Achatz, hearing the fuss from the kitchen, texted Kokonas that something was going to come of it. “She was acting really wild,” Achatz recalls.

Sure enough, at about 1:30 a.m., Cora ripped Alinea in an Instagram post, complaining about the lack of a table, griping that Achatz “didn’t even come out” from the kitchen, labeling the personnel as “arrogant, disrespectful,” and saying Achatz should learn lessons from, among others, the late Charlie Trotter (“your mentor and my friend” — though Trotter’s relationship with Achatz was notoriously un-mentor-like).

Achatz texted Kokonas again when her post went up. Kokonas said in response, “You know what? I’m just going to tell our side of the story.”

Kokonas did just that later that morning in a lengthy post titled “Into the Litter Box” on the website Medium. It began: “If you’re Cat Cora & dead wrong, best not to post to Instagram.” He proceeded to offer a minute-by-minute, receipt- and email-filled account of how Cora “intentionally arrived 24 hours and 15 minutes late to a booking at Alinea, proceeded to create a scene, accuse our staff of sexism, invoked a ‘chef’s code’ whereby we were expected to ‘roll a table into the kitchen’ for her, and then left with ‘fuck you, fuck Grant, fuck Alinea’ while flipping off one of our kindest veteran servers, who tried mightily to apologize even though the situation was not his fault.”

The Cat spat went national and inspired popcorn-eating GIFs on Twitter. The Washington Post asked in a headline: “Who’s at Fault in Reservation Mix-Up?” Tim Forster of Eater scolded Cora for her behavior but also wrote that Kokonas’s “potshots and lengthy take-down weren’t a good look, either, for someone who purports to provide excellent hospitality.”

Even Achatz had misgivings. He never would have responded, he says, “but as soon as [Cora’s Instagram post] went up, Nick was on Medium, and he was enjoying it.”

Kokonas offers no apologies, saying that if Cora had kept her dissatisfaction private, he would have held back. “Also,” he adds, “I’m right. If you’re right, make sure everyone knows that you’re right.”

Cora’s publicist declined a request for comment, emailing, “Cat has moved on from the interaction I assume you are talking about and wishes Nick, Grant, and Alinea the best.”

But Kokonas wasn’t ready to let it go. More than a month after the flare-up, he tweeted a photo of himself in front of a Cat Cora restaurant in San Francisco’s airport, writing: “Open back up … I’m friends with the chef. ;-)”

“If I would’ve done that, oh God, I would’ve gotten lectured: ‘You can’t do that. You’ve got to take the high road,’ ” Achatz says. “But, man, he had no problem.”

Kokonas and Achatz’s relationship has always been a matter of sharp contrasts. Speaking to McDonald’s corporate executives this spring, Kokonas summed up the distinction this way: “He’s narrow and a mile deep, and I’m shallow but a mile wide.” (Kokonas’s shallowness is selective, though; when he homes in on a subject, it becomes an obsession, such as his 2017 social media quest to find exceptional casual pants. Amid an outpouring of suggestions, he created a spreadsheet detailing pages’ worth of brands and test-drove numerous pairs, and he says he’d like to continue his mission via a men’s pants blog sometime in the future.)

Though both are strong-willed, Kokonas loves to talk things out, even when he’s in smartest-person-in-the-room mode, while Achatz will sometimes communicate his wishes in his pin-drop-quiet kitchens without ever uttering a word.

Still, former Alinea chef de cuisine Jeff Pikus sees similarities: “Nick wants to constantly find ways to improve [the restaurant industry], change it, make it better, just the same way that Grant wants to think about food in ways that other people haven’t.” Adds Dave Beran, who served as Alinea’s chef de cuisine and then Next’s executive chef for its first five years: “Nick has crazy, far-fetched ideas, and so does Achatz. Sometimes in business, people find their perfect other half. For Achatz, that was Nick.”

The two met in 2002 at the Evanston restaurant Trio, where Achatz was chef de cuisine. Nick and Dagmara kept a standing Wednesday reservation. Achatz, who had spent more than four years under Thomas Keller at the French Laundry in Napa Valley, was running his own kitchen for the first time and earning raves for his inventive tasting menus. Still, the shy chef rarely showed his face in the dining room.

It wasn’t long, though, before he realized that Kokonas understood him. While most diners marveled at the novelty of Achatz’s mozzarella balloon filled with tomato foam, Kokonas took it in and said, “Oh, caprese salad.” One conceptual thinker had met another.

One night Kokonas told him, “If you ever consider leaving here to open your own thing, I would be happy to help you.”

“He just left it at that,” Achatz says. “He wasn’t pushy. And then we started a dialogue via email, and the more I got to know him, the more I liked him and the more I felt like we connected.”

At that point, Kokonas was between industry conquests. He grew up an only child in Northbrook and studied philosophy at Colgate University in upstate New York, where he met Dagmara. She first noticed him as the guy who would wear one of four identical (other than the color) cashmere sweaters to their philosophy of law class.

His maiden entrepreneurial venture came after he graduated: selling art posters to college students and doctors’ offices. He soon took a job with the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, starting as a runner with the hopes of becoming a trader. The plan worked. He made a lot of money, formed his own derivatives trading firm, and executed the first of his many disruptions when he had his company set up, despite fierce objections, the first closed cellular network so that the firm’s traders in Chicago and New York could communicate directly from their respective stock exchange pits, rather than rely on the time-wasting traditional system of relayed hand signals.

From the high volume of transactions in the trading world, Kokonas saw the effects of “outcome bias,” people’s tendency to judge decisions based on the results rather than the underlying reasoning. He realized that it’s more important to be right most of the time than it is to get hung up on any single decision. Casinos, after all, thrive because they keep the long-term odds on their side. “When I get emails asking for life advice, which I do every day now, I cannot give any beyond: Own something, make lots of decisions that have outcomes, try to be right 51 percent of the time, do that often, and repeat,” Kokonas says.

But not everything can be factored into a formula, and in 2001 Kokonas found his own world disrupted. That February, his father, who had been his role model, died of cancer. Seven months later, Kokonas’s firm had more than 30 people working at the American Stock Exchange, blocks from the World Trade Center, when the towers came down. A week later, while Kokonas was telling employees they still didn’t need to return to work, one of his partners was fretting over how much money they were losing. “I just said to them, ‘I think I’m done,’ ” Kokonas recalls.

He took several months extricating himself from the firm, and afterward played golf and traveled to as many Michelin-starred restaurants in Europe as he could. But he realized that none of those meals compared to Achatz’s food in Evanston. Eventually, the two took the plunge on Alinea with a handshake and no formal operating agreement. Kokonas even fronted Achatz’s share of the fifty-fifty partnership. “I didn’t have any money, so he wrote me a loan so I could then put money back in so that we could be even,” Achatz says. “Like, who does that?” Though the restaurant business is notoriously thorny, Dagmara was “thrilled” her husband was making the leap. “Out of 300 people he talked to in the first eight months of that project, zero of them other than myself were supportive. Zero.”

A year and a half after Alinea’s 2005 opening, Gourmet magazine was deeming it the best restaurant in America. Not long after, Alinea was scaling the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list and the James Beard Foundation named Achatz the country’s most outstanding chef. Alinea’s continued reign among the elite seems all the more miraculous given that a little less than two years in, Achatz was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer of the tongue. His struggle has been well documented, particularly in his and Kokonas’s 2011 memoir, Life, On the Line, but Achatz still marvels at Kokonas’s response. “He was right there in the room, like he was my father, my big brother,” Achatz says. Kokonas took him to appointments and advocated the care that ultimately saved his life. “There was his literal ‘No, we’re not going to give up.’ ”

Given his far-flung energies, Achatz says, Kokonas bristles at being characterized as the mere money guy propping up the artist: “He gets really frustrated when people don’t think that he’s a creative.” Perhaps because of that, Kokonas isn’t shy about noting which ideas were his. “I feel like Next and the Aviary were largely my contribution to the restaurant world,” he says, recounting how he conceived of the latter in the aftermath of abortive talks with Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump Jr. about bringing a dining concept to Chicago’s then-new Trump Tower. (Kokonas was ultimately scared off by the current president’s reputation for breaking contracts but gives props to Ivanka as “the youngest person in the room and most prepared.”)

Kokonas also spearheaded last year’s The Aviary Cocktail Book, though Achatz would have preferred a follow-up to the popular 2008 cookbook Alinea. (Disclosure: I worked with the two on an early stage of Alinea before we parted ways.) “In terms of breaking new ground on a new book, The Aviary was more interesting,” says Kokonas. He eschewed the traditional trappings of making a cookbook: This one used no recipe testers or food stylists, and its lush photography was shot over the course of two years rather than a couple of weeks. He even hired and relocated husband-and-wife visual effects artists Sarah and Allen Hemberger — who worked, respectively, at Industrial Light & Magic and Pixar in the Bay Area — to assemble the project.

In addition to being a creative success, the book represented Kokonas’s self-proclaimed triumph over the publishing industry. The Alinea Group is the publisher, using Amazon as one of several fulfillment centers, so it sets the price ($85 for the standard hardcover, $135 for the boxed reserve edition) and collects the money as well as the buyer data. The first printing of 30,000 was sold out by late spring, with another 40,000 copies available starting this summer.

One recent morning, Kokonas, the Hembergers, and Alinea Group business development manager Alex Hayes were seated around a table conceptualizing an upcoming holiday supplement to the book. As they compared publications of various sizes and discussed paper quality, it was abundantly clear who would be making the final calls.

“Do you care about flaps?” Hayes asked.

“No flaps,” Kokonas said.

What about a slipcase?

“We don’t want to get into book territory. I feel really strongly about that.”

“If given the choice of smaller and thicker or bigger and thinner?”

“Go bigger and thinner,” Kokonas said, lifting a journal that was the size he preferred.

His zoom-in management style can have its complications. Julie Hyatt, Alinea’s office manager for its first four years, describes him as “a thoughtful guy, well traveled, really intellectually curious and well read,” and she appreciated the support he would offer when she had a personal issue. But, she says, he was better with ideas than process and didn’t necessarily understand how other people worked, so his intervention could create “chaos,” with him being “super involved” before suddenly jumping to another project. For Pikus, the former Alinea chef, the work culture became an issue: “There’s a lot of ego in that company, which is something I never liked. That’s part of the reason I didn’t stay longer.”

Kokonas can be impetuous at times. He was so dismissive of designer Martin Kastner’s first attempt at the Alinea logo that he almost fired him — until Achatz persuaded his partner that they needed to communicate their ideas better. Kastner’s next attempt, an elegant rendering of the Latin paragraph sign (called an alinea), stuck.

“He’s convincible,” says Kastner, who eventually partnered his firm, Crucial Detail, with the Alinea Group. “He hears people out. He’s super approachable, very genuine, but also doesn’t take any prisoners. There’s a level of honesty that’s just hardcore, and it takes a little getting used to.”

Some never get used to it. And Kokonas has accumulated a considerable list of enemies to show for it. Former Esquire restaurant critic John Mariani says Kokonas “caused me a lot of crap” when, in Life, On the Line, the restaurateur accused Mariani of swiping Alinea’s steel-bound wine list, which he emphatically denies. More recently, Kokonas banned Mariani from Alinea Group restaurants after the writer used a photo of a postcancer Achatz to crack wise about not trusting “a skinny chef.” Mariani says he was making a curmudgeonly joke that had nothing to do with Achatz’s illness. As for his Alinea ban: “They need not worry that I will try to sneak in in disguise.”

In another media dustup, Kokonas implied on Twitter that New York Post restaurant columnist Steve Cuozzo had made an enemy of the Alinea Group after his “hit job” in late 2017 against Tock, which came a couple of weeks after the writer dubbed the Aviary “New York’s most ridiculous bar.”

“He’s just a shitty journalist,” Kokonas says now with a laugh. “Like, that guy doesn’t know food. The New York Post is a rag, right?”

“But if it’s a rag, why respond?” I ask.

“I didn’t respond very much. I just said this guy’s an idiot.”

Says Cuozzo: “I thought this fellow Nick was pretty thin-skinned to go nuts over one or two pieces that I wrote.”

Kokonas even seized an opportunity to tweak the U.S. president while engaging in some self-promotion. In January, after Trump treated the newly crowned NCAA champion Clemson Tigers football team to a fast-food meal in the White House during the government shutdown, Kokonas tweeted an invitation for the players and coaches to experience “an actual celebration dinner” at Chicago’s Alinea Group restaurants.

But in late June, he found himself playing defense, carefully, in response to reports that an Aviary server had spat on Eric Trump while the president’s son was at the West Loop cocktail bar. Kokonas crafted an official statement that was circumspect and diplomatic, noting that the server had been placed on leave and decrying both those who had threatened to boycott the business (“based on the actions of a lone individual”) and those who had praised the server’s alleged actions (“A degrading act lowers the tenor of debate”).

Ordinary diners are not immune from Kokonas’s wrath. One Chicago banker ranted on Yelp about how the “complete assbags” at Next wouldn’t refund his money when he missed his reservation. Kokonas detailed on Facebook why the guy didn’t deserve a refund, and the New York Observer figured out the diner’s full name and published it. “I only call out assholes,” Kokonas says. “It’s very simple.”

Most of his clashes, he notes, never go public. “We had a really high-ranking executive of a big company at Next getting very drunk, telling very bad jokes, and he finally grabbed one of our servers inappropriately, and I went over to the table and kicked him out instantly,” Kokonas says. “You just don’t harass our team. He was like, ‘Do you know who I am?’ I said, ‘Yeah, you’re the guy who’s going to be on the front page of the paper tomorrow night if you don’t get out of here and leave a $500 tip in the process.’ And he was like, ‘That’s extortion.’ I’m like, ‘Yeah. Get the fuck out of my restaurant. You’re not welcome here ever, and I will keep this private as long as you do.’ ”

Then there was the would-be solo diner who complained far and wide that he could never snag Alinea’s sole reservation slot for a single diner. “He’s written me on my Facebook, Instagram, personal email, work email, Yelp, Zagat, and he contacted [ABC-7 food reporter] Steve Dolinsky,” Kokonas says. “I finally just emailed him and said, ‘I am now going to make 50 one-tops available, and you’re not going to be one of them. I’m not going to let you in ever.’ ”

For Kokonas, the smackdown wasn’t just a matter of settling a personal score. It was about numbers. Alinea usually offers only one booking a night for a single diner simply because the restaurant earns more when two people are seated at that same table. Alinea generally doesn’t book parties of three anymore for the same reason. “We used to do an average of six four-tops as three-tops every night, and you multiply that out by seven times a week, 52 weeks, that’s $1.2 million a year in [lost] revenue.”

I ask him if that’s the best message to send out, hospitalitywise.

“Fuck it,” Kokonas interjects. “That’s why restaurants are closing, man.”

Alinea would close if it did three-tops?

“Yeah,” he says, adding: “If you have a waitlist of 250 people a night, and you’re agnostic as to who comes, why wouldn’t you sell a four-top instead of a three? The thing that bothers me most in the world is that no one pauses to think for a second. It’s like, ‘OK, well, are they just being pedantic? Are they just doing this to annoy me? Or maybe there’s a reason for it, and maybe the world doesn’t revolve around me.’ ”

It was that kind of logic — the balancing of hospitality and economics — that led Kokonas to create his innovative Tock reservation system. At the time, Alinea was missing out on more than 100 customers a month due to parties either not showing up or arriving with fewer people than in their reservation. “If someone cancels Alinea five minutes beforehand, I can’t sell that,” he says.

Given that Alinea always presented itself as a form of entertainment, Kokonas reasoned, why not sell tickets as you would to the theater, a concert, or a sports event? He introduced his concept at Next, a high-demand opening as Achatz’s first post-Alinea project. All transactions took place online, no phones, and you paid in advance, the price of the tasting menu meal varying with the day of the week and the time of day.

Achatz was unsure of this approach at first. “It was the nonhuman aspect of it. It was the pay-in-advance. It was anti everything that I learned [about hospitality] up until that point in my career. He was like, ‘It can be way better.’ And he was right. He was way ahead of the game.”

Soon Kokonas was adding unaffiliated restaurants to the Tock system — at a rate of 150 a month now. A renowned trio of Thomas Keller spots — the French Laundry, Per Se, and Ad Hoc — and the venerable Chicago restaurant group Lettuce Entertain You are among Tock’s clients. (Tock now offers restaurants the option of a traditional reservation system.) Rich Melman, Lettuce’s founder and chairman, became a Tock investor. The system is less expensive than competitor OpenTable, Melman says, and solves the problem of no-shows, which he estimates accounted for an 8 to 12 percent loss of sales at Lettuce. “Nick has figured out how to take that down to almost nothing,” Melman says. “He just thinks differently.”

But the approach has ruffled some feathers. Joe Catterson, Alinea’s general manager from its opening until 2012, was uncomfortable putting fine-dining hospitality in a similar league as, say, a Bulls game. “People have legitimate reasons for changing plans at the last minute,” he says. “Do you really want to be the business that’s not accommodating of that?”

Kokonas counters that his restaurants will refund money in extreme situations — but they won’t always take customers’ word for it. “If someone claims their plane was delayed, we just say, ‘Send me your flight info.’ ” Some excuses have become all too familiar. “We have No-Show Bingo,” he says, sharing a game card with 25 squares that include “Grandma Died,” “Dog Is Sick,” “Just Got Dumped,” “Babysitter Bailed,” and “Another Grandma Died.”

“For some reason, people just throw their grandmother under the bus the most.” He pauses, considering. “This is a terrible part of the interview.”

Kokonas has no qualms about knocking the competition. Tock’s software, he says, can do much more than OpenTable’s, which can’t sell specific events such as a Mother’s Day brunch. “My ideal endgame is that I take over OpenTable,” Kokonas says. “They could buy us and make me the CEO, and I could run the industry the right way. They know this. I tell them this all the time.”

Steve Hafner, CEO of OpenTable parent company Kayak, says he has, in fact, been told this multiple times by Kokonas. Hafner acknowledges that Tock has come up with some better software, but says it lacks OpenTable’s sales infrastructure. Not to mention a 16-year head start. “I don’t lose any sleep at night because of Tock,” he says.

Still, Hafner enjoys the rivalry, quoting from the 2004 King Arthur movie in describing Kokonas: “Finally, a man worth killing.”

Kokonas is picking “Here Comes the Sun” on his Collings electric guitar in his music room, a low-ceilinged basement sanctuary that Dagmara carved out for him during a renovation of their Old Town home. Several six- and 12-string acoustic guitars are mounted on the walls, with a full drum kit in the center and a well-worn bass guitar to the side. The bass, a 50th birthday present from Dagmara, originally belonged to John Stirratt from Wilco, Kokonas’s favorite band.

The room has come in extra handy of late, helping him cope with his “massive” stress level. “There’s a phrase that a partner of mine used to use, which is that if you wake up throwing up, you’re taking too much risk. If you wake up and you feel great, you’re not taking enough risk. If you wake up with a nice, even nausea all the time, that’s the right amount of risk. So I’m fairly nauseous all the time.”

Dagmara thinks her husband’s next pivot will involve music. Kokonas already has visions of an ultra-high-end club that would combine live acoustic performances and fine dining in the Fulton Market space formerly occupied by the late Homaro Cantu’s Moto and a furniture store (the Alinea Group pays $250,000 a year to control that real estate). He imagines something like Manhattan’s fabled Stork Club of the mid-20th century, a place where elites might sip a fancy cocktail, eat a Michelin three-star meal, and enjoy a top entertainer of the day in an intimate setting.

“This is the greatest musicians in the world, greatest artists in the world, spoken word, comedians,” Kokonas says. “Could I sell it for $1,500 a ticket if you’re going to get Champagne, an entire meal, and you see Wynton Marsalis in a room of a hundred people, tops? With the best acoustics in the world? Fuck yeah, I could sell that every day of the year.”

He says he has already pitched the concept to “household-name folks of every genre” (though not Marsalis) and received favorable responses. Such a venue doesn’t exist anymore, he notes. “We expect you to get dressed up and show up. It’s adult world.”

“Rich adult world,” I crack.

“Is the Chicago Bears rich adult world?” Kokonas shoots back. “Forty thousand people there, but it’s really fucking expensive.”

A nerve has been touched.

“People get very political about food, but they think nothing of spending $500 for two people to go see Lady Gaga,” he continues. “So you can go to Alinea for $210 and get a two-and-a-half-hour, 14-course meal, or you can go see the Bears, get a hot dog, a beer, and watch men beat on each other. Personally, I’d rather go have the dinner.”

He plays the riff of the Violent Femmes’ “Blister in the Sun.” The high-end club project is on hold, and Kokonas, once again, is restless.

“Every 10 years, I’ve gotten a new career: trading from ’93 to ’03, Alinea from ’05 to ’15, and Tock started in ’14, though Alinea keeps going.” He’d cash out, he says, if the price were right.

In the meantime, Kokonas has found another industry to conquer: writing. Aside from compiling his thoughts on business philosophy for a potential book, he is working on a novel and a screenplay simultaneously; he finishes a chapter and then converts it into script form. “I go, ‘Oh, this is easy. Let’s get some dialogue in there and a couple pans.’ ”

I tell him this is an insane approach because screenplays are structured differently from novels, and a novel contains way more information.

“I’m trying to write a book that feels like a movie,” he says. And that’s that.