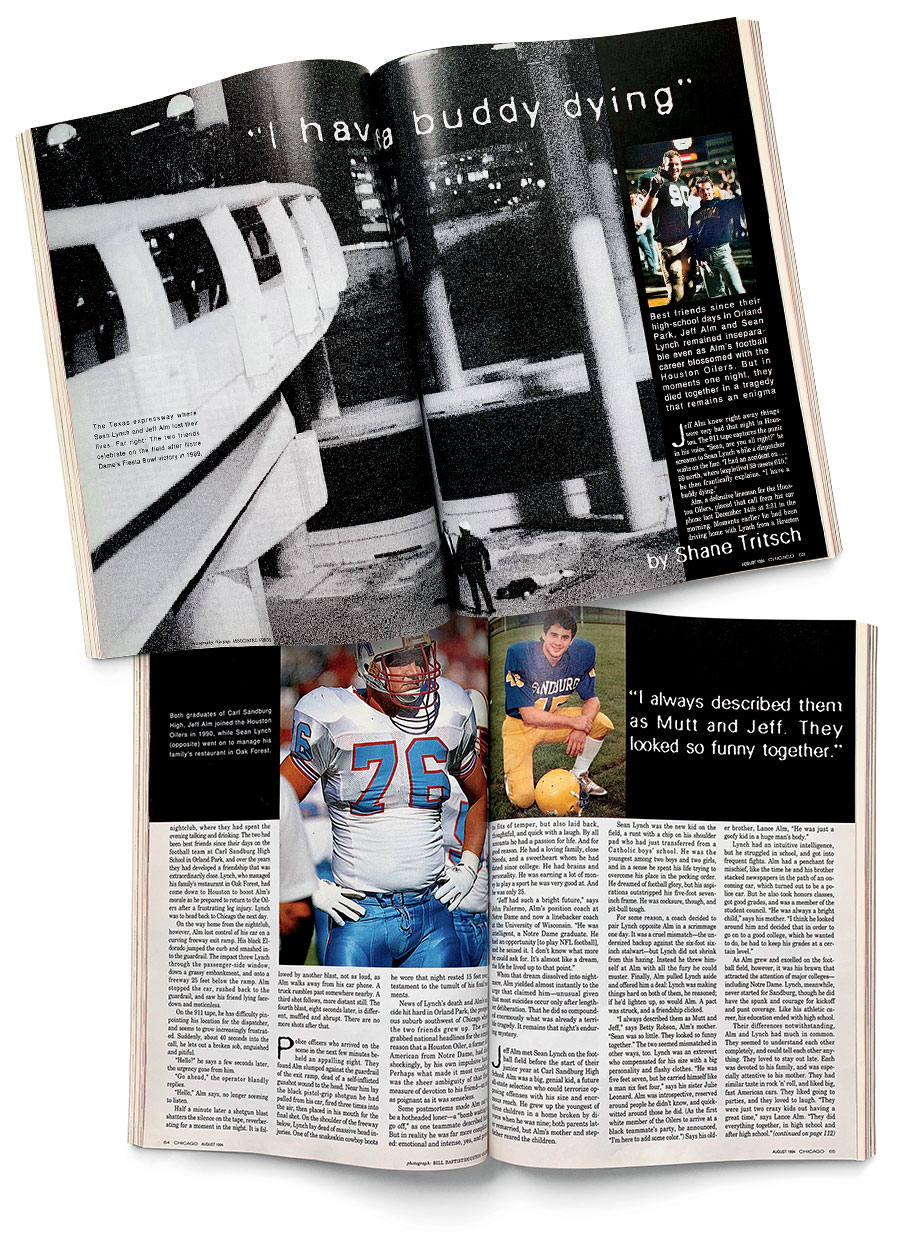

A golden boy from Orland Park, Jeff Alm became an All-American linebacker at Notre Dame before being drafted into the NFL in 1990 by the Houston Oilers. But he didn’t leave his local roots behind: His closest relationship remained with his high school best friend, Sean Lynch. In the August 1994 Chicago story “ ‘I Have a Buddy Dying,’ ” Shane Tritsch explored the deep bond between the two men.

Alm used to concoct a hypothetical scenario in which he was stranded in downtown Chicago at three in the morning after he and Lynch had had a fight. As he once explained to Christine Boron [his girlfriend], the one person in the world he would call to rescue him was Lynch, however angry he might be; Alm knew Lynch wouldn’t hesitate to come.

As Tritsch’s story recounts, in December 1993, Lynch visited Alm in Houston and the friends spent a night on the town. In the early morning hours, Alm, whose blood alcohol level of 0.14 percent was above Texas’s legal limit at the time of 0.10 percent, crashed his Cadillac Eldorado into an exit ramp barrier. Lynch was thrown through the passenger window and fatally injured. Alm, not seriously hurt, saw what had happened to his friend, made a frantic call to 911, then ended his own life with the shotgun he kept in his car. The deaths shook Orland Park as the national media reported on the promising 25-year-old player’s tragic choice.

Alm’s and Lynch’s funerals were held on the same day in Worth and Orland Park, respectively. The Oilers dedicated the rest of the season to Alm and wore helmets bearing his number, 76.

Read the full story below.

“I Have a Buddy Dying”

Best friends since their high-school days in Orland Park, Jeff Alm and Sean Lynch remained inseparable even as Alm’s football career blossomed with the Houston Oilers. But in moments one night, they died together in a tragedy that remains an enigma.

Jeff Alm knew right away things were very bad that night in Houston. The 911 tape captures the panic in his voice. “Sean, are you all right?” he screams to Sean Lynch while a dispatcher waits on the line. “I had an accident on… 59 north, where [expletive] 59 meets 610.” he then frantically explains. “I have a buddy dying.”

Alm, a defensive lineman for the Houston Oilers, placed that call from his car phone last December 14th at 2:31 in the morning. Moments earlier he had been driving home with Lynch from a Houston nightclub, where they had spent the evening talking and drinking. The two had been best friends since their days on the football team at Carl Sandburg High School in Orland Park, and over the years they had developed a friendship that was extraordinarily close. Lynch, who managed his family’s restaurant in Oak Forest, had come down to Houston to boost Alm’s morale as he prepared to return to the Oilers after a frustrating leg injury. Lynch was to head back to Chicago the next day.

On the way home from the nightclub, however, Alm lost control of his car on a curving freeway exit ramp. His black Eldorado jumped the curb and smashed into the guardrail. The impact threw Lynch through the passenger-side window, down a grassy embankment, and onto a freeway 25 feet below the ramp. Alm stopped the car, rushed back to the guardrail, and saw his friend lying facedown and motionless.

On the 911 tape, he has difficulty pinpointing his location for the dispatcher, and seems to grow increasingly frustrated. Suddenly, about 40 seconds into the call, he lets out a broken sob, anguished and pitiful.

“Hello?” he says a few seconds later, the urgency gone from him.

“Go ahead,” the operator blandly replies.

“Hello,” Alm says, no longer seeming to listen.

Half a minute later a shotgun blast shatters the silence on the tape, reverberating for a moment in the night. It is followed by another blast, not as loud, as Alm walks away from his car phone. A truck rumbles past somewhere nearby. A third shot follows, more distinct still. The fourth blast, eight seconds later, is different, muffled and abrupt. There are no more shots after that.

Police officers who arrived on the scene in the next few minutes beheld an appalling sight. They found Alm slumped against the guardrail of the exit ramp, dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. Near him lay the black pistol-grip shotgun he had pulled from his car, fired three times into the air, then placed in his mouth for the final shot. On the shoulder of the freeway below, Lynch lay dead of massive head injuries. One of the snakeskin cowboy boots he wore that night rested 15 feet away, testament to the tumult of his final moments.

News of Lynch’s death and Alm’s suicide hit hard in Orland Park, the prosperous suburb southwest of Chicago where the two friends grew up. The story grabbed national headlines for the simple reason that a Houston Oiler, a former All-American from Notre Dame, had died shockingly, by his own impulsive hand. Perhaps what made it most troubling was the sheer ambiguity of that final measure of devotion to his friend — an act as poignant as it was senseless.

Some postmortems made Alm out to be a hotheaded loner — a “bomb waiting to go off,” as one teammate described him. But in reality he was far more complicated: emotional and intense, yes, and prone to fits of temper, but also laid back, thoughtful, and quick with a laugh. By all accounts he had a passion for life. And for good reason. He had a loving family, close friends, and a sweetheart whom he had dated since college. He had brains and personality. He was earning a lot of money to play a sport he was very good at. And he was only 25.

“Jeff had such a bright future,” says John Palermo, Alm’s position coach at Notre Dame and now a linebacker coach at the University of Wisconsin. “He was intelligent, a Notre Dame graduate. He had an opportunity [to play NFL football], and he seized it. I don’t know what more he could ask for. It’s almost like a dream, the life he lived up to that point.”

When that dream dissolved into nightmare, Alm yielded almost instantly to the urge that claimed him — unusual given that most suicides occur only after lengthier deliberation. That he did so compounded enormously what was already a terrible tragedy. It remains that night’s enduring mystery.

Jeff Alm met Sean Lynch on the football field before the start of their junior year at Carl Sandburg High School. Alm was a big, genial kid, a future all-state selection who could terrorize opposing offenses with his size and enormous reach. He grew up the youngest of three children in a home broken by divorce when he was nine; both parents later remarried, but Alm’s mother and stepfather reared the children.

Sean Lynch was the new kid on the field, a runt with a chip on his shoulder pad who just transferred from a Catholic boys’ school. He was the youngest among two boys and two girls, and in a sense he spent his life trying to overcome his place in the pecking order. He dreamed of football glory, but his aspirations outstripped his five-foot seven-inch frame. He was cocksure, though, and pit-bull tough.

For some reason, a coach decided to pair Lynch opposite Alm in a scrimmage one day. It was a cruel mismatch — the undersized backup against the six-foot six-inch stalwart — but Lynch did not shrink from this hazing. Instead he threw himself at Alm with all the fury he could muster. Finally, Alm pulled Lynch aside and offered him a deal: Lynch was making things hard on both of them, he reasoned; if he’d lighten up, so would Alm. A pact was struck, and a friendship clicked.

“I always described them as Mutt and Jeff,” says Betty Robson, Alm’s mother. “Sean was so little. They looked so funny together.’ The two seemed mismatched in other ways, too. Lynch was an extrovert who compensated for his size with a big personality and flashy clothes. “He was five feet seven, but he carried himself like a man six feet four,” says his sister Julie Leonard. Alm was introspective, reserved around people he didn’t know, and quick-witted around those he did. (As the first white member of the Oilers to arrive at a black teammate’s party, he announced “I’m here to add some color.”) Says his older brother, Lance Alm, “He was just a goofy kid in a huge man’s body.”

Lynch had an intuitive intelligence, but he struggled in school, and got into frequent fights. Alm had a penchant for mischief, like the time he and his brother stacked newspapers in the path of an oncoming car, which turned out to be a police car. But he also took honors classes, got good grades, and was a member of the student council. “He was always a bright child,” says his mother. “I think he looked around him and decided that to go on to a good college, which he wanted to do, he had to keep his grades at a certain level.”

As Alm grew and excelled on the football field, however, it was his brawn that attracted the attention of major colleges — including Notre Dame. Lynch, meanwhile, never started for Sandburg, though he did have the spunk and courage for kickoff and punt coverage. Like his athletic career, his education ended with high school.

Their differences notwithstanding, Alm and Lynch had much in common. They seemed to understand each other completely, and could tell each other anything. They loved to stay out late. Each as devoted to his family, and was especially attentive to his mother. They had similar taste in rock ’n’ roll, and liked big, fast American cars. They liked going to parties, and they loved to laugh. “They were just two crazy kids out having a great time,” says Lance Alm. “They did everything together, in high school and after high school.”

When Alm left for Notre Dame, Lynch spent a few years searching for his own path close to home — although sometimes he seemed more interested in perfecting his water-skiing skills at his family’s Michigan cottage than in figuring out his future. He worked in construction for a while, made plans to go to college in Arizona, then postponed college when he was badly injured in a car accident. Finally, he began managing Jack Gibbons Gardens, the popular Oak Forest steakhouse owned by his father.

Meanwhile, distance did nothing to diminish his friendship with Alm. Lynch journeyed frequently to see his friend in South Bend. When Notre Dame went to the Fiesta Bowl on January 2, 1989, to play for the national championship, he came out to watch, then joined Alm on the field in triumphant celebration afterward. When NFL draft day arrived, Lynch was at Alm’s side again when he was chosen by the Oilers in the second round.

“All the important moments of their lives, they shared,” says Beth Pjosek, Lynch’s girlfriend of two years. “They just had this very close bond. Jeff accomplished a lot of Sean’s dreams. I think [Sean] was proud of the fact that Jeff went to school and got his degree, and that he played professional football. I think he saw in Jeff a lot of things he wished he would have been able to do but didn’t.

“I think Jeff looked at Sean and saw that he had a lot of street smarts, and that Sean was a people person; he could talk to anybody. And I don’t think Jeff had that ability. They just complemented each other.”

If the two weren’t together, they stayed connected almost daily by phone, sharing every development of their lives and helping each other through the rough parts. When Alm went through a rocky relationship with a girlfriend, Lynch helped him pick up the pieces. When Lynch had an argument with his brother, Alm dispensed logical advice. “There was an awful lot of trust, an awful lot of history, an awful lot of counseling between the two of them,” says Christine Boron, who dated Alm at Notre Dame and lived with him for two and a half years . “They just accepted each other unconditionally, regardless of their differences.”

When Alm came home during summers in college and the NFL off-season, he and Lynch “were inseparable,” says Boron. They had other close friends with whom they often did things. But a perfect evening was just the two of them going out to a restaurant, then to a bar that was quiet where they could talk. When the bars closed, they would head back to Gibbons, invade the bar and kitchen, and prepare banquets of steak and cab legs at three or four in the morning. Eventually they’d go home, perhaps to vie against one another in computer games or to watch late-night movies. Sometimes they wouldn’t call it a night until the sun had risen; then they’d sleep till mid-afternoon, get up, and do it again.

At Notre Dame, Alm poured his energy into football. “He was a kid who worked hard all the time because he wasn’t a great athlete. It was never a gift for him,” says Lance Alm. “He went to Notre Dame with the thought that he was going to do everything it takes to make pro football. He worked his butt off, and he made it.”

But it wasn’t just the hard work that made Alm excel, says lance. What truly separated him from other players of comparable size and ability was his state of mind. “If you go out there and say, ‘I’m going to try hard and become the best I can be,’ that’s wonderful. But if you don’t go out on that field and say, ‘I’m going to kick the shit out of somebody,’ then you’re not going to make it in the NFL. You have to be big and bad to make it. Not even big. You have to be bad. And he was.”

Chicago Bears defensive lineman Chris Zorich, who played beside Alm at Notre Dame, remembers how different Alm could be on the field and off. “He was a nice guy off the field — relaxed and calm,” Zorich says. “But it was like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. On the field he could maul people. He was the heart of our defense.” Adds coach Palermo, “Jeff was a very intense player. He played the game hard and was a pleasure to coach.”

Alm was named a second-team All-American his senior year, thus making him one of the most coveted defensive lineman of that year’s NFL draft. Yet for all his accomplishments, he seemed ambivalent about the sport to which he devoted so much. “He never got personally involved in football,” says his father, Larry Alm, a marketing consultant who lives with his second wife in Burnsville, Minnesota. “If he could have made that kind of money doing something else, I think he would have done it.”

Alm seemed determined to stake out a life for himself beyond football. He worked hard on his degree in marketing — not exactly a dumb-jock major. And unlike many of his teammates, he did not spend much free time hanging out with other ballplayers. “Most of his best friends were people outside of football,” says Matt Cramer, a nonballplayer who roomed with Alm for three years and married one of Alm’s closest friends from childhood. “You spend 14 hours a day living and breathing football, and some people are going to want a break from it. I think that was one reason Jeff and Sean were such good friends.”

At a school that worships its football players almost as fervently as it hails the Virgin Mary, Alm seemed uneasy with the attention. “He wanted to be accepted for himself and not for what he was doing,” says his mother. “He didn’t like the limelight and the fuss people made over him.”

The more attention Alm received for his football exploits, the more guarded he became. Strangers wanted to be his friend, shake his hand, or, conversely, challenge him to see how tough he was. “A lot of people wanted a piece of him,” says Larry Alm. “Just to get through the day he had to be careful about giving out too many of those pieces. He was not that way growing up but I think he became that way after he became as successful as he did.”

In Houston, Alm found himself alone, far from his family and friends, visible and vulnerable. He made some friends on the Oilers, but he remained tightest with five or six friends from home and college. Foremost among them was Lynch, with whom he still spoke almost every day and whom he welcomed as a guest a few times each year.

Before he visited Alm in Houston last December, Lynch had a curious, recurring dream that now seems hauntingly prescient. In it he was riding a roller coaster; its ascents and descents took him through the peaks and pits of his life. Up and down it went until, at the end of his dream, it just kept climbing.

After the growing pains of his youth and the car accident that derailed his college plans, Lynch seemed headed for one of those peaks. He had found his niche working as a manager and greeter in his father’s restaurant. He took pride in his wardrobe, spending lavishly on colorful ties and double-breasted suits. He seemed to relish the responsibility and attention his work brought him. In recent years he spearheaded a beautification of the restaurant’s interior and outside grounds, and he was brimming with other plans for the place.

“When he was younger, work didn’t concern him,” says Bill Cooper, one of Lynch’s closest friends. “He just wanted to go out and have a good time. The last two years or so, he really got into work. He was really maturing.”

Along with his job and family, friends completed the most important trinity of Lynch’s life. And he would do anything for his friends. “If you were bummed, he wanted to make you happy,” remembers Cooper. “If you were in a spot, he did anything he could to get you out of it.”

That weekend last December, Lynch knew his best friend was in a spot. Indeed, Alm was enduring his most frustrating football season, a year marred by a bitter contract holdout and an injury that had caused him to miss all but two games.

“Jeff was really upset because he had injured his knee,” says Beth Pjosek. “They were talking about it maybe being the end of his career. Sean knew that Jeff needed him at the time.”

As badly as things had gone for Alm that season, he had good reason to be upbeat by the time Lynch arrived. With his injury almost healed, he was to begin practicing with the team the day Lynch was scheduled to head back to Chicago. His goal was to “kick some ass,” as he told a reporter, and improve his bargaining power for next season.

Lynch’s visit had been short but packed with good times, including a bikini contest he and Alm judged, and the Oilers game on Sunday. Alm got Lynch a pass to watch the game from the sidelines, where the players stood — a thrill for him. Monday was to be their farewell evening together, a chance to get a little crazy and cap off what had been a great four days.

Before embarking that night, Alm told his sister Debbie O’Connor, by phone that he and Sean were going out on the town. “My parting words to him were ‘Be careful,’” says O’Connor, who knew that drinking and driving sometimes mixed when her brother and Lynch got together. “He said they would take a cab if things got out of hand. I said that was a great idea.”

They piled into Alm’s Cadillac and headed out for a steak dinner. Later they went to a nightclub, where they had drinks and stayed until closing. As usual, Lynch was no wearing his seat belt for the ride home; in fact, he almost never buckled up despite his earlier serious accident. As he often did, Alm was driving fast when he lost control f the car — an estimated 63 miles an hour, according to investigators, well above the exit ramp’s posted limit of 40. Toxicology tests revealed that his blood-alcohol content was 0.14 percent, topping the legal threshold in Texas of 0.10; Lynch was at three times the legal limit.

“They really thought they were immortal,” says Lynch’s sister Julie Leonard. “They believed that there was a force field surrounding them, that nothing could touch them — which made them no different from most 25-year-olds. They were like Butch and Sundance — larger than life. And they went down in a blaze of glory.”

Jeff Alm started keeping guns after he began playing for the Oilers. Matt Cramer, who once accompanied him to a Houston range to shoot handguns, recalls that he was scrupulous about safety. “He didn’t shoot a gun for the first three months he owned one,” Cramer says. “He took it apart and put it together ten times. He said, ’They’re dangerous weapons, and if you don’t know what you’re doing, someone could get hurt.’ He was always careful to wear earplugs and goggles [when he shot]. And he would always clean his guns when he got back from the range.”

Alm was equally deliberate about other areas of his life. His townhouse was immaculate, his closet organized by types of clothing — shirts segregated from pants and suits, and subdivided into casual and dressy. He saved his stereo boxes so that when he moved he could repack the components in their original cartons. He was fanatical about maintaining the proper balance of chemicals in his hot tub, and about keeping his car spotless. He kept careful files of all his paperwork.

“Jeff was a thorough guy,” says Larry Alm. “He had files of bank records, utility bills, records on everything. He was the most organized person you’ve ever seen. He had a will and an executor named. He very seldom did anything impulsively. He thought about it, and he was methodical.”

Alm brought that same sense of order to his personal life as well. “When he counseled Sean, he was rational to the point where the answer was evident and not so emotionally decided,” says Boron. “He used to do that with me and it would drive me crazy. Because he takes away your power of argument by being so rational.”

There was a part of Alm that was less rational, however, a fast-driving, quick-tempered side that seemed to court the edge that he finally went over that night in Houston. Perhaps it was the same part — highly aggressive, exuding an aura of invincibility — that enabled him to thrive amid the sanctioned brutality of NFL football. Whatever its basis, though, football certainly seemed to bring it out in him.

“During the football season and right before it, e was always very easily sparked by things that upset him,” says Boron. “He’d attribute that to the season. Playing football, it’s hard to walk off the field and be a normal person with a normal temper. He used to say that if you don’t go out there and pound the other guy harder, you’re not going to make it.”

“You don’t just turn things on and turn them off,” says Lance Alm. “Of course [football] spilled over into his life. It made him more aggressive, a lot quicker tempered.”

Alm wished he could turn off the primal impulses that helped him flourish on the football field. He even wrote in a journal that he needed to learn to neutralize his anger, according to Boron. At times, he seemed to have as much control over it as a volcano has over its eruptions.

Alm raged, for example, when drivers cut him off on the expressway. “I don’t know what it was,” says Sean Jones, a former Oilers teammate who now plays for the Green Bay Packers. “He hated it, hated it, hated it.” Often Alm would retaliate by cutting the offending motorist off, or by shouting and gesturing menacingly. “I would never get in a car with Jeff,” says Jones. “He drove like a madman.”

During one such incident, a woman driver brandished a gun. Unnerved, Alm apparently began carrying his own gun under his car seat — the Winchester Defender model he would use on himself. But later, in another high-speed altercation, Alm allegedly pointed the gun at another motorist. Alm was later questioned by police, but the other driver decided not to press charges.

Alcohol didn’t mix well with Alm’s temper. At a bar in Houston, he allegedly knocked out a man who he thought was picking on Lynch. The single punch was so damaging that the man had to get reconstructive surgery; the resulting lawsuit against Alm was settled out of court.

Several friends contend that Alm did not fight without reason or provocation. But his father, for one, believes that it was “booze” that propelled Alm into the occasional barroom brawl. “I don’t think Jeff ever drank very well,” Larry Alm says. “When he did, he tended to be a little looser, less inhibited.”

It is tempting, in the context of Alm’s suicide, to cite such volatility to explain why he did what he did — to conclude that in the crucible of his last moments in the rational Alm, the one who practiced gun safety and called 911 to summon help for his friend, gave way to the more explosive Alm who could knock out a man with one blow or allegedly wave a gun at another driver.

It becomes even more tempting when one considers that such aggressive behavior has been associated with a heightened risk of suicide, according to David Clark, director of the Center for Suicide Research and Prevention at Rush — Presbyterian — St. Luke’s Medical Center. Drinking and carrying a gun also heighten the association with suicidal risk, he says.

“We tend to think that people who carry a gun close to them have a quality of impulsivity and aggressiveness that makes for a variety of problems, including suicidal risk,” Clark says. “He was capable of pulling it out and brandishing it in an argument on the highway. That speaks to qualities of hotheadedness and aggressiveness that aren’t true of all football players. That’s not to explain why he [committed suicide], but it’s a piece of the puzzle.”

One wonders what the outcome might have been that night had Alm not had instant access to a gun, or not been drinking/ Still, the people who knew Alm best say the only piece of the puzzle that begins to explain what went wrong is the extraordinary bond he shared with Lynch — and the howling despair he felt over his friend’s death.

“It was a moment of irrationality brought on by being alone on an abandoned highway,” says Boron. “There was no one around. Nine-one-one didn’t seem very helpful. He looks down and sees the one person in the world who understood hm best. He made the decision that his life would not be the same without his friend. I don’t think it was a judgment, that ‘I did this terrible thing,’; it was ‘I lost one of the most important people in the world.’ ”

“Some people can’t understand it — choosing to kill yourself just because a buddy is gone,” says Brad Siensa, a close friend of Alm and Lynch and the only person to be a pallbearer at both men’s funerals. “But because it was Sean, I totally understand. They were best friends. Always talking. Always talking. It didn’t matter if it was three in the morning or one in the afternoon, or whether Jeff was in Orland Park or Houston. Jeff never would have been the same — not without Sean.”

“It was an unthought-out action, a reaction to the situation,” says Alm’s sister, Debbie O’Connor. “And if he thought about the repercussions a little, it never would have happened. But I think [Sean’s death] would have changed him completely. I don’t think he could have lived with that on a daily basis. It would have ruined his spirit.”

Alm used to concoct a hypothetical scenario in which he was stranded in downtown Chicago at three in the morning after he and Lynch had a fight. As he once explained to Christine Boron, the one person in the world he would call to rescue him was Lynch, however angry he might be; Alm knew Lynch wouldn’t hesitate to come.

At 2:30 in the morning of December 14th, Alm found himself stranded near downtown Houston and utterly alone. He had a phone at his fingertips that might have been his lifeline to people who loved him. But the one person in all the world he would have called could no longer rescue him. “Sean was not there and that was unbearable,” Boron says. “It’s sad to say that I wasn’t enough, but I’m sure he wasn’t thinking about me at the time.”

Did Alm think of any of the loved ones who would grieve after he pulled the trigger? “Sometimes when people get as scared or anguished as they are when they take their own lives, they can lose almost total sight of the people who are there for them,” says David Clark. “Their mind becomes such a labyrinth, such a cavern, that they got lost inside.”

Wandering helpless in his own labyrinth, alone and far from home, Jeff Alm put down the phone and picked up the gun. He went walking toward his best friend, away from life.