Burden: “I believe only a soldier can tell you what it is like to be a soldier in Iraq.”

|

When an American soldier named Mathew Schram was killed in Iraq in 2003, a friend of his, a Gulf War veteran from Chicago named Matthew Currier Burden, agonized that the death seemed to have passed relatively unnoticed, even by the reporter who was embedded with Schram’s unit when his convoy was ambushed by insurgents. So Burden started a blog, Blackfive.net—writing about the people fighting the war and those who don’t come back. “It is just as much Mat Schram’s blog as it is mine,” he says. (Burden says “Blackfive” is “an old military call sign for the executive officer who makes things happen behind the scenes.”)

There were only a few military bloggers back then. Now there are hundreds. Early on, Burden got only about 300 hits a day; now it’s up to four million unique visits and about ten million views (meaning some people go there more than once a day) per year, making Blackfive arguably the most prominent military blog, or milblog, as they’re called, in the blogosphere. Though he claims that Blackfive is neither pro- nor antiwar and is nonpartisan, Burden has a decidedly conservative slant, and he (and his regular contributors to the blog) tend to defend the Iraq war against criticism by politicians and the media.

Whatever their views of the war, milblogs have given voice to the soldiers on the 21st-century battlefront. They have also attracted the attention of military officials, who have cracked down on military blogs, citing the “possibility” of “accidentally” giving troop movement or casualty information to the enemy. Since April 2005, soldier bloggers in Iraq and Afghanistan have had to register their Web sites, and any blogs or sites they contribute to, with their commanders, who may monitor their blogs to see that they aren’t inadvertently releasing classified security information. Citing security concerns, the Pentagon has also blocked soldiers’ access to 13 popular networking, music, and photo-sharing sites, including YouTube and MySpace, on Department of Defense computers.

Even with new restrictions, Blackfive has become a main source of information for today’s young soldiers to communicate between the battlefront and the home front. It is read by servicemen and -women, their families, the brass at the Pentagon, journalists, and even the White House. This form of war reporting, possibly even more than that of embedded journalists, is likely to be the real wave of the future.

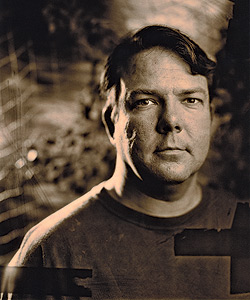

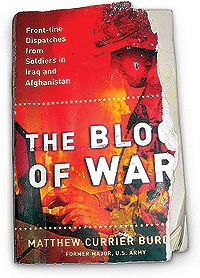

Burden, 39, grew up in the Ravenswood neighborhood, where his father was an Episcopal priest. He is a diehard Cubs fan, a deep-dish pizza aficionado, and graduate of UIC and the University of Chicago, where he got a master’s in computer science (he is currently in an MBA program at the University of Illinois). Today, he is an information technology executive, married, and the father of two children. His book The Blog of War was published in 2006 by Simon & Schuster. In it, he collected many of Blackfive’s blog entries as a way to share the hopes, fears, concerns, and deep patriotism of these young servicemen and -women who post, as well as the views of their families.

Burden, a former army officer and Gulf War veteran, assembles his machine gun in a 1987 photo.

|

Q: What is the genesis of Blackfive?

A: In the beginning there were about 200 people communicating over the Internet whose thoughts were not in sync with news reports. I received calls and e-mails from friends serving and the stories they told were contradicting media accounts. Their stories focused on local events and people—their successes and failures. The honesty of those posts was missing from media coverage. Blackfive provided an opportunity to publish them in a coherent place. Most soldiers are proud of what they are trying to do and want to express it. Blackfive also raises money to help returning soldiers get the kind of medical and mental health help they need.

Q: How did you know you were on to something bigger than communicating with friends, and friends of friends?

A: For the first six months, even though I was getting thousands of visits a day, I didn’t know how powerful the medium was until early 2004, when a soldier was grievously wounded (he lost both legs and an arm) and his mother was notified by the army that he was being moved to Walter Reed in Washington, D.C. She lived in North Carolina; his fiancée was in Texas. He hadn’t woken up, so he didn’t know what had happened to him yet. All the free housing for wounded soldiers’ families was full and his mother had to figure out a way to pay for a place to stay in D.C. He was looking at a year minimum in the hospital. What should she do? I wasn’t going to let her lose everything, so I put out a plea for help on the blog. In less than 48 hours we had raised $30,000 to support the family. Last November military blogs raised over $200,000 in one week to help support wounded soldiers. It runs the gamut from a VP of a large company who wrote a personal check for $25,000, to a Dallas waitress who pledged her tips for a month to help the wounded.

Q: The tech genie is out of the bottle. How will military blogs balance government concerns about openness with the need soldiers have to communicate with each other?

A: I don’t think the powers-that-be understood the Internet generation. Soldiers flooding the war zones brought iPods, laptops, cell phones with cameras, digital cameras—it was certainly a Pandora’s box for the military. Each year the military increases restrictions on communication from soldiers to family and friends. Now soldiers must register their blogs and Web sites with their chain of command, and they must observe Operation Security Measures when communicating. Anything useful to the enemy is forbidden without approval. I’d like to see bloggers have the same restrictions as embedded journalists—no more, no less.

Q: Why is Blackfive so popular, and who is it popular with?

A: I have been surprised that cable news producers, general officers, soldiers, and even journalists have paid attention to us. We are subject matter experts, but we aren’t slick and we aren’t paid for our opinions. Most importantly, we resonate with the military family (active duty, Reserve or Guard, retired vets) because we write passionately and honestly as a voice for them.

Q: You have gotten a lot of personal attention for Blackfive; what do you see as your role?

A: I am just a conduit. I post the stories, connect people who want to help or send support. As much as people credit me for strengthening their faith in military men and women, those same people have renewed my faith in civilian Americans.

Q: Who reads military blogs aside from those directly involved?

A: Americans who want to know what it is like to be a soldier in a war zone or a family member left behind. Many want to know more about the Iraqis and the Afghanis. People read blogs for balance, as much media coverage focuses on our failures.

Q: Do these blogs deepen our understanding, or contradict what we hear in mainstream media?

A: Both. Bloggers will never replace mainstream media coverage but they do supplement how people get their news.

Q: How do bloggers, and Blackfive in particular, look for balance?

A: There is a sign at a marine outpost in Iraq that reads, “America is not at war. The Marines are at war. America is at the mall.” We have tried to look for ways to tell our stories that will be heard by those not doing the fighting.

This copy of Burden’s book The Blog of War (Simon & Schuster; 2006) that belonged to a National Guardsman withstood a humvee explosion in Iraq.

|

Q: Do you have examples of specific moments that were covered by the Department of Defense, journalists, and bloggers differently?

A: A CNN news executive, Eason Jordan, reported that American soldiers were intentionally targeting [i.e., shooting] journalists. We questioned it on the blog until the media started to look into it. Jordan eventually resigned from CNN. We helped explain the ties between antiwar groups planting people in the military (called astroturfing) so they’d have more legitimacy espousing antiwar views. I think Abu Ghraib was worked into many stories that had nothing to do with what happened at Abu Ghraib, so we highlighted those differences. We have tried to look for places where our knowledge can balance or challenge common thinking.

Q: Do the blogs confirm government statements about the war or contradict them?

A: Both. The Pentagon and the Department of Defense aren’t in the business of trying to spin the war as much as many people think they are. They put out information and it’s up to the media to use it, question it, investigate it, or discard it.

Q: How good is local and national media coverage of the war?

A: Local news tends to do a better job covering local soldiers and hometown units. Annie Sweeney and John Sall at the Sun-Times did great work in a series called “The Chicago Boys,” about the local National Guard helicopter unit in Iraq. Nationally, I think highly of The New York Times’ John Burns and CNN’s Arwa Damon and Nic Robertson.

Q: Why do you think military blogs give people a better sense of what is going on locally on the ground?

A: The number of reporters in the war zone has dropped from hundreds to dozens, although the surge has sent some back to cover the war. In the end I believe only a soldier can tell you what it is like to be a soldier in Iraq.

Q: Is war reportage changed forever now?

A: Yes. Blogging has influenced the media, which influences public opinion. Now embedded reporters have blogs, too.

Q: What will be the role of blogs when the war is over?

A: When the war ends in Iraq and Afghanistan, it won’t end here at home. The hundreds of thousands of vets who have been in the war zone will need treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injuries that the Veterans Administration isn’t prepared for even now. Our next fight will be to ensure that vets get the treatment they deserve. We have a captive, motivated audience donating time and money, writing to Congress, shaping public opinion, and we will act. We will disseminate the success stories: people who sought help, received it, and got better—to remove the stigma of even reporting the symptoms.

Milblogs that Matthew Burden recommends:

Andrew Olmstead

Left his own blog to blog about his deployment for the Rocky Mountain News