Related:

Chicago’s Asian carp threat—what you should know »

MORE JEANNE GANG:

Hear Gang talk about her visionary plan for the Chicago River at a panel (led by Chicago editor Geoffrey Johnson) at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum (2430 N. Cannon Dr.; 773-755-5100) on December 7 at 7 p.m. For more information, go to naturemuseum.org.

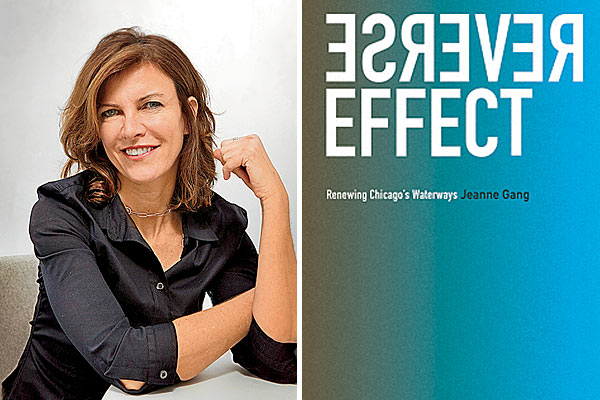

Read Gang’s Reverse Effect: Renewing Chicago’s Waterways ($30 at amazon.com).

She is best known as the architect behind a host of notable Chicago buildings, including the futuristic Aqua—and for winning a MacArthur Fellowship (the so-called genius grant) in September. But Jeanne Gang is also an urban planner with strong views about the Chicago River and the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. In her new book, Reverse Effect: Renewing Chicago’s Waterways, she argues that a permanent barrier between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River could vastly improve the city. (The proposed barrier would be just northeast of Bubbly Creek and Canal Origins Park, which is at 2701 South Ashland Avenue.) Gang talked with Chicago senior editor Geoffrey Johnson about Reverse Effect, a few of her other projects, and whether she might be the city’s next Daniel Burnham. Here is a condensed version of their conversation. A shorter, edited version appeared in our December print issue.

GJ: Reverse Effect seems as much a call to arms as a spur to the imagination.

JG: This is supposed to be a book that inspires people to do more. It shows how we [Gang, her colleagues at Studio Gang, and her Harvard design students] started to think about what the future of the river could be—how it could be brought into the city as a part of the urban fabric and connect the Bridgeport and Pilsen neighborhoods. How we could reverse the way we’ve been thinking about the river, so that the ecology, the landscape, the urbanism, the architecture—everything could be brought together into some inspired thinking.

GJ: One of the key elements of Reverse Effect are the steps you outline for using a river barrier at Bubbly Creek as a catalyst to transforming the city.

JG: This is a vision we’re putting forward as a potential road map for what to do with the river down there. This is the area where combined sewer and storm water goes to the Racine Pumping Station. Then it gets treated somewhat at the Stickney Water Reclamation Plant. In fact, a lot of it is released without disinfection, and then it goes down to the Gulf of Mexico via the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal [the 111-year-old engineering project that, among other things, reversed the flow of the Chicago River].

Meanwhile, the riverfront area around Bubbly Creek has a band of industrial land that could start to be acquired. It’s basically defunct. All the big industries down there are not coming back. Once that’s done, we would start to introduce green infrastructure: permeable pavement that allows storm water, which is not that dirty, to go straight down into the aquifer and back into the lake. Every time you redo a street, you upgrade it to the permeable pavement instead of solid. You also redesign the tree planters so that water is funneled to them from the street. It takes the water load off at the point source, instead of dumping fresh rainwater into the sewer system. All that would keep our basements drier.

Next you would install this barrier, hydrological separation, dam—whatever you want to call it—basically reestablishing the divide between the Mississippi River watershed and the Great Lakes. It’s also, suddenly, a connection between Bridgeport and Pilsen. The whole book is looking at the barrier as a catalyst to reimagining [this part of the city].

The next step is to take out the canal—which is a concrete basin—and remediate the area so it can start to operate like a wetland. Use nature as technology. The wetlands will increase the amount of waterfront, increase the amount of green space, and increase property values on either side of the river. Then start to invest in more water treatment. Instead of pumping sewage and the overflow into Stickney, you could just treat it here. We need to expand our wastewater treatment. Use biodigesters to clean the water basically and return it to the wetlands for the last polishing.

Now we’d move the dam or build another dam. Instead of flushing water down to the Gulf of Mexico, we start reclaiming it. This is when you reverse the flow of the Chicago River, finally. Suddenly you’re catching the billions of gallons of fresh water a day that we drain from Lake Michigan and bringing it back to the lake.

Imagine Chicago repeating this step at these various inlets. That would create these incredible new inland waterways that become part of the urban fabric. It would be amazing. All of these places would have harbors and boats and water access, things that we just don’t have now.

GJ: Do you see a time frame for this?

JG: Quite honestly, I don’t know. It could go fast or it could go slow. This is a vision for the long term. The purpose of this book is to say, here’s one way—an opportunity to create a huge asset for the city. This is one scenario that could be amazing as a transformation of our river.

GJ: How did you get involved in this project?

JG: I’ve been involved with environmental issues in Chicago from the start of my practice. Actually, my thesis when I was at Harvard was about aerating and improving the Chicago River downtown. And I’ve been building up a pretty strong working knowledge of hydrology and green infrastructure potential. The idea to reverse the flow of the river and separate the watersheds has been floated out there, and there are a number of environmental groups that support it. One reason is because of the Asian carp. For this specific project, the NRDC—Natural Resources Defense Council—pointed out the location that they had in mind.

GJ: Some people refer to the Asian carp as a poster boy—a quick way for people to connect with this complex problem.

JG: [The carp and other invasive aquatic species] are connected to all kinds of issues about water quality and underused industrial land, which is oftentimes polluted as well. So we have these things right in our midst. It’s very important to have people living in the city and creating density where public transportation is, where the jobs are. There’s tons of underutilized land here, and it becomes derelict. It makes it so people in the city don’t think of the river as a place to go. They go outside the city to try to see a natural river, and we have one right here. But we treat it like a sewer.

GJ: Toward the end of Reverse Effect, you write about how the manipulation of the landscape made Chicago happen. You’re imagining a new manipulation of the landscape, although in some ways it’s a restoration.

JG: I’d say it’s still manipulation. The fact that it’s been manipulated so much gives you the freedom to think about it. We can design it any way we want.

GJ: When you talked with your students at Harvard, you raised the issues of the barrier, flooding, and water quality. But there’s so much more going on here.

JG: I wanted them to think of the river and the scale of the problem. Here’s something that’s relatively small and local, basically a dam in the river. But it connects to these much greater regional systems, like shipping and invasive species and the connection between neighborhoods. I think the future of architecture is going to be more and more dealing with these more complex systems, instead of just doing a building.

GJ: Are you optimistic that this is going to happen?

JG: Those kinds of things are easy. We just have to start doing them. That we will eventually get a cleaner system—yes, I’m optimistic. But we need legislation to make it happen. People won’t just do it on their own.

GJ: Can we talk about a few of your other projects? What’s the status on the Ford Calumet Environmental Center? [Slated for 134th Street and Torrence Avenue, the as-yet unbuilt project recently won a Holcim Award for Sustainable Construction.]

JG: I’m hoping something like the Holcim prize will help spur it on. I think it’s a perfect project for [the Emanuel] administration, because it is in a neighborhood that is underserved. Hegewisch Marsh—I mean, talk about getting dumped on. It would be a spark to some economic activity there. But look at our economy. If there were money to be found that could help it move forward, that would be really great. But as of right now, we haven’t heard of it advancing anywhere.

GJ: Talking about the Ford Calumet project, you write, “Form follows availability.”

JG: It’s a different way to think about design. Usually we design and then bid it out. But what if we designed with what was available? So when the time comes to get the materials, you can use those that are available and close by. That reduces the amount of energy for shipping it.

GJ: What about your high-rise residential project in Hyderabad, India?

JG: On hold. But we’re destined to work in India. I love that place. There are a lot of things being done in India that are greener than what we’re doing here. They start from the low tech and gear it up from there. One of the things they do is create compressed blocks that are made of soil or clay from the site—but they’re not fired, so they actually produce less carbon. It would be a great thing to try to use here.

GJ: Are you our new Daniel Burnham?

JG: [Laughter] I admire what Burnham was able to do. But post-Fire, he had a rather blank slate. If we can pull something off here, it will have to do with tying a lot of those threads together. I think of me and my team as—he was the leadoff hitter and we’re batting cleanup in the bottom of the ninth. The stakes couldn’t be higher, right?

Photography: Chris Walker/Chicago Tribune