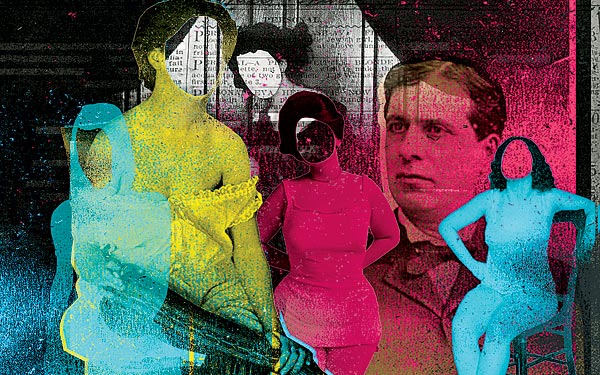

In 1895, a grand jury indicted Dunlop (pictured above) for mailing “obscene, lewd, lascivious and indecent” materials contained in his newspaper’s personal ads. Two years later, he went to jail.

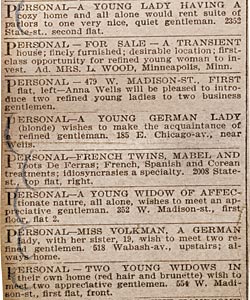

By the summer of 1895, anyone who glanced through the classified ad section of a feisty young newspaper called the Chicago Dispatch would have noticed a curious phenomenon: Dozens of women used the forum to announce their desire to meet gentlemen. Many ladies specified the sort of men they wanted to see: “refined,” “appreciative,” “liberal.” They were even more specific in describing themselves: “TALL, HANDSOME LADY, magnificent form”; “A VOLUPTUOUS JEWISH LADY from Aurora”; “TWO NICE-LOOKING LADIES, blonde and brunette”; “LADY WITH BEAUTIFUL RED hair”; “A JOLLY YOUNG IRISH GIRL in her own flat”; “YOUNG ARTIST’S MODEL OUT of a position.”

None of the ads said anything about sex, but because many invited men to visit addresses in Chicago’s red-light districts, guardians of the city’s morals thought they knew full well the underlying agenda. “It was simply a directory of the vile houses of the town,” said John Alexander Dowie, a prominent Chicago preacher of the time.

More than a century before the Cook County sheriff Thomas Dart filed a civil lawsuit against Craigslist, arguing that the popular website should be held responsible for allowing prostitution ads, federal prosecutors went after the Chicago Dispatch publisher Joseph R. Dunlop for a similar offense. The authorities took different approaches, and the cases had different outcomes: A judge rejected Dart’s suit, while Dunlop served almost two years in prison. But the cases also have much in common, despite the years that separate them. And a comparison of the two highlights some of the complex and nuanced issues presented by the emergence of the Internet.

* * *

The son of an Irish clergyman, Joseph R. Dunlop moved from Canada to Chicago in 1867, when he was 18. Writing and editing for a variety of newspapers, he developed a reputation for producing lively and entertaining stories. One reporter who worked for him recalled, “He spent a good half hour telling us about the kind of paragraphs he wanted: they had to be smoking, every paragraph had to curl somebody’s hair.”

In 1892, Dunlop founded the Chicago Dispatch, which eagerly boasted about its independence and fearless reporting. A promotional ad proclaimed: “Any newspaper which has no enemies doesn’t deserve to have friends.” Dunlop later recalled that the Dispatch exposed “pulpit fraud,” insurance scams, and political corruption. Critics claimed he had a different agenda: They accused Dunlop of blackmailing people by threatening to publish reputation-ruining articles.

Only a few copies of the Dispatch are available today, so it’s hard to say whether the paper really was as “ultra-sensational” as some claimed. Judging from the four issues at the Chicago History Museum, the Dispatch looks like a typical paper of the 1890s, lacking the sort of lurid headlines that would burst onto front pages with the arrival of William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago American in 1900.

By 1894, the Dispatch was the “Official Paper” of the city of Chicago and Cook County, printing all legal notices for those governments. Dunlop’s rivals said he monopolized those notices by making ludicrously low bids, printing them at a loss so he could gain a veneer of respectability. Nine major daily English-language newspapers were vying for readers in those days, and in 1895 the Dispatch claimed to have a circulation of 65,000, second in the evening only to the Daily News, which sold about 200,000 copies.

The Dispatch made its debut not long after a New York moral crusader named Anthony Comstock had spurred the U.S. Post Office to wage a war against obscenity. In 1873, Congress had passed the Comstock Law, cracking down on sending obscene material through the mail.

Between 1873 and 1913, federal authorities in Chicago prosecuted about 500 cases involving obscene mail, according to the scholar Shirley J. Burton’s 1991 study of the case files. During most of that era, about one-tenth of all criminal cases at the Chicago federal court were Comstock Law prosecutions. Some Illinoisans were arrested for mailing lurid novels or pinup photographs of “Sporty Girls.” Authorities also attacked books containing advice about sex, and people were hauled into court for writing personal letters and post cards containing sexual language or innuendo.

The local crackdown was handled by a postal inspector based in St. Louis, Missouri, Robert W. McAfee, who was also the agent for the Western Society for the Suppression of Vice, a regional counterpart of Comstock’s New York censorship group. In 1894, McAfee visited the Dispatch’s offices and warned Dunlop against mailing copies of his newspaper containing lewd advertisements. Dunlop later portrayed himself as the victim of a conspiracy. He maintained that powerful Chicagoans who had been investigated by the Dispatch were trying to drive him out of business and that rival publishers were ganging up on him.

The forces aligned against Dunlop included John Alexander Dowie, leader of the Christian Catholic Church at Chicago’s Zion Tabernacle (and later the founder of the religious colony of Zion in Lake County). Dowie visited the U.S. postmaster general, William Wilson, and showed him the Dispatch. “I want this paper thrown out of the mails,” Dowie said. Recounting the conversation, Dowie quoted Wilson as replying, “God helping me . . . I will see that . . . its publisher is punished.”

On October 24, 1895, a federal grand jury in Chicago indicted Dunlop for mailing copies of the Dispatch containing “obscene, lewd, lascivious and indecent matters.” Oddly, the jurors listed the categories under which the ads appeared but refused to repeat what the ads said because they were “so indecent.”

The cited ads included promotions for male virility drugs, a breast-enlargement product, and “regulator tablets,” which were allegedly abortion aids.

One ad described “a company of young ladies” performing “a novel entertainment introducing unique features.” But most of the ads were notices from women seeking to meet men. For example, Miss Lillian Walsh suggested that her friends should stop by her new home, 164 Custom House Place (now Federal Street). A year earlier, William Stead’s book If Christ Came to Chicago! had identified that address as a “house of ill-fame.”

Illustration: Mario Wagner

* * *

When Dunlop went on trial in 1896, prosecutors presented nothing to prove that prostitution was taking place as a result of the ads. The U.S. district attorney, John Black, simply read some of the notices aloud and pronounced that the ads spoke “the foul tongue of harlotry and lewdness in every invitation.” He asked the jury, “Is there a man among you who can doubt what these things mean?”

Help Wanted: Just a tiny sampling of the surprisingly frank advertisements that ran in the Chicago Dispatch, one of the city’s leading newspapers

Dunlop’s attorney, William S. Forrest, did not mention the First Amendment, but he did argue that Chicago had a different standard for obscenity than small towns. And he pointed out that the Dispatch was hardly the only source of information on prostitutes. “The idea that it is necessary for a country boy to go to a newspaper to find the haunts of wicked women is ridiculous,” he said. “Why, she’ll find him before he has been in town two hours.”

Instructing the jury, the U.S. district court judge Peter Grosscup defined “obscenity” as anything calculated to deprave a reader’s morals or “lead to impure purposes.” The jury found Dunlop guilty.

Judge Grosscup handed down one of the era’s harshest sentences for obscene mail—two years in prison and a $2,000 fine—a decision met with approval from Dunlop’s rival publishers. A Times-Herald editorial called the sentence a “just desert” for Dunlop, who was a “blackmailer, procurer, corrupter of youth and debaucher of public morals.” A Tribune editorial said it had been “reckless” and “despicable” for Dunlop to publish the ads.

Dunlop appealed his case to the Supreme Court and continued running the Dispatch while he was out on bail. He admitted to a visitor that in the past he had published ads for “business interests of alleged questionable reputation.” But Dunlop pointed out that city officials allowed these businesses to stay open. So who was he to say that the businesses couldn’t publish ads?

In February 1897, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously upheld Dunlop’s obscenity conviction. The question, wrote Justice Henry Billings Brown, was “whether persons of ordinary intelligence would have any difficulty of divining the intention of the advertiser.”

President McKinley rejected a request for clemency, and on May 5, 1897, Dunlop, 48, was locked up in Joliet, where he would stay 21 months. His newspaper folded while he was in prison, but after his release Dunlop founded a weekly version of the Dispatch, which survived for a decade. He died in 1926.

Yellowed clippings of the Dispatch ads now sit in old federal court records stored at the National Archives at Chicago, evidence of what was once considered obscene.

Richard R. John, a historian and professor at Columbia University in New York, says, “[The Comstock Law] ceased to be systematically enforced by about the time of the First World War.” The law was the forerunner of today’s federal statutes banning obscene mail, which authorities use in cases of child pornography.

“There are laws like that on the books today,” says Geoffrey Stone, a University of Chicago law professor and First Amendment expert. But it’s unlikely someone like Dunlop would be prosecuted now for mailing similar ads, because the definition of obscenity is much narrower. “In those days, you could throw around very loosely words like ‘obscene,’ ‘lascivious,’ ‘lustful,’ and so on, and it wasn’t at all clear what the crime was,” Stone says. “It was just sexy.”

* * *

The advertisements that Sheriff Dart found on Craigslist were not nearly as circumspect as those Dispatch ads from 1895. One example: “Teens for CASH . . . Young Hot GIrlSS!!! open all night! $150!!!!!!! $100 quickie. youngest and hottest girls in chicagoland. . . .”

Facing pressure from attorneys general around the nation, Craigslist revamped its “erotic services” section in 2008, requiring people who post a suggestive ad to give a working phone number and pay a $10 fee. The San Francisco–based site also includes warnings against ads for illegal activities.

Dart’s investigators use ads on Craigslist to find and arrest prostitutes, but Dart says that some of the worst offenders in the transaction—the pimps—hide in the Internet’s anonymity. “It was a lot easier before,” he says. “You visually could see the guy who was grabbing people at the end of the day or grabbing their money. Now, he is on the Internet. He’s got the 15-year-old’s website set up for her. She’s never met him.”

Last March, Dart sued Craigslist Inc. in U.S. district court here, claiming the website created a public nuisance and seeking a permanent injunction to block the site from publishing ads for prostitution. “I’m not some Deep South, conservative, Bible-thumping sheriff that’s out to crack down on pornography and tell people how to live their lives,” Dart says. “How many more children do I have to save from being raped? How many more people do I have to save who are trafficked?”

Two months later, Craigslist announced more changes: “Erotic services” became “adult services.” The Craigslist CEO, Jim Buckmaster, told CNN, “Each ad is going to be read by a human and the image looked at by a human to verify that that ad is in full compliance, not only with the law but also with our terms of use and posting guidelines.” Buckmaster added that the changes Craigslist had made in 2008 had eliminated “95 percent of the inappropriate activity on the site in this category.”

Dart disagrees. “The photographs, the advertisements are not as provocative,” he says. “Is it as raunchy as it was before? No. . . . Are we making as many arrests as we were before? Absolutely. So has anything of substance changed? No.”

Dart’s case rested on a 1970 Supreme Court ruling that said the First Amendment does not protect commercial advertisements promoting illegal activities. “We have no doubt that a newspaper constitutionally could be forbidden to publish a want ad proposing a sale of narcotics or soliciting prostitutes,” Justice Lewis Powell wrote.

The same principle should apply to a website, argued Daniel Gallagher, an attorney for the Chicago law firm Querrey & Harrow, which handled the 2009 case pro bono for Dart. “This case is about . . . a business on the Internet acting in a way that no brick-and-mortar establishment ever could,” Gallagher told the judge. “A business cannot ignore the havoc it wreaks.”

But lawyers for Craigslist maintained that federal law protects “online service providers” from lawsuits like the one filed by Dart.

Geoffrey Stone says the question comes down to whether Craigslist is more like a newspaper, which takes an active role in publishing, or a telephone company, which allows people to communicate without monitoring what they’re saying. “We don’t hold the phone company liable for the things people say over the phone,” Stone explains. He points out that no one would serve as a phone-company executive if those executives risked going to prison for life because somebody used the phone to cook up a murder. “If you want people to have a phone system, you have to provide a certain degree of immunity to the people who run the system.”

Dart’s lawyers argued that Craigslist plays a more active role than the phone company. They claimed that by setting up an adult services category, the website promotes criminal activity. But Eric Brandfonbrener, a Chicago attorney for Craigslist, told the court that the company doesn’t do anything to encourage crimes. It “simply provides its users with a blank text box in which to describe their offered services,” he wrote.

In the Dispatch case more than a hundred years ago, Dunlop had similarly questioned his responsibility for the ads in his newspaper. The publisher told the postal inspector Robert McAfee that he “scarcely ever saw the advertisements . . . until after they had been published.” Dunlop also told McAfee “that he was publishing a metropolitan paper, and all those things were phases of metropolitan life and he did not see where to draw the line.” But John Black, the prosecutor, warned against letting publishers shirk responsibility—the result, Black argued, would be newspapers that “mix defamation, scandal and outrage . . . overflowing the land with infamy.”

Last October, Judge John F. Grady of the U.S. district court dismissed Dart’s lawsuit. Craigslist is not a publisher, he said, so it can’t be held responsible for prostitution ads posted by other people. “Sheriff Dart may continue to use Craigslist’s website to identify and pursue individuals who post allegedly unlawful content,” Grady concluded. “But he cannot sue Craigslist for their conduct.” A New York Times editorial hailed the decision as “A Win for Internet Speech.”

In an e-mail, Jim Buckmaster says, “Craigslist is unusually responsive to law enforcement, and hopes this ruling encourages a more constructive approach by Sheriff Dart.”

Dart decided against appealing the decision. But he argues that if the courts continue to read the law this way, then the law should be changed. As for the Dunlop case, Dart had never heard of it, and it was not cited in any of the pleadings. But told of the case, Dart says he feels angry that people treated the publication of prostitution ads more seriously in 1895 than they do today. “I don’t know where our society’s gotten,” he says. “We allow people to hide behind legal doctrines, where people are objectively getting hurt.”

Words, pictures, and sounds flow more freely today than anyone in the 1890s could have imagined. Still, when Craigslist and its supporters defend the Internet’s freewheeling forums, they echo a comment that Joseph Dunlop made more than a century ago. “The Dispatch does not create immorality,” he said.

Photograph: Robert Loerzel/courtesy of National Archives Great Lakes Region