When Jessica Blumberg graduated magna cum laude from Warren Township High School in Gurnee, she had plenty of enviable options for where to go to college. For one, she got into the highly ranked engineering school at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. But in the end, she rebuffed her home state’s school and headed west, to the University of Iowa.

Why? Iowa was a bargain. It offered a financial aid package that brought costs down to about $16,000 a year—20 percent less than she’d have paid at Illinois, even with in-state tuition. “It was an easy decision because Iowa was so much cheaper,” says Blumberg, now a college junior.

She and thousands of other students are following the money. Illinois is now the nation’s largest net exporter of freshmen to other states’ public colleges. Rising tuition in the University of Illinois system, uncertainty about financial aid, and aggressive recruiting from nearby states—it’s all contributing to the exodus.

Illinois has bled more students than it’s brought in for a while, but the trend has accelerated in the past couple of years as the state’s budget woes have exacted a toll on the University of Illinois and other public schools. In 2014—the most recent year for which data are available—Illinois saw a net emigration of 12,700 students, a 70 percent increase over a decade.

The big repercussion is that talented students may never return. “It’s a serious brain drain,” says William Morrison, a college counselor at Highland Park High School. It’s common for students to stay put after graduation: Almost half of the Urbana alumni who are alive still reside in Illinois.

At the root of all this are cuts in state funding that have forced Illinois schools to raise base tuition and fees. At Urbana, in-state rates rose 59 percent over the past 10 years, to a minimum of $15,700 and a maximum of $20,700 (not including room and board), depending on the major. At the same time, financial aid through the state’s Monetary Award Program, which provides need-based grants to residents, doesn’t go as far as it used to. It’s not even clear from term to term whether funds will be available: In a survey released in December by the Illinois Student Assistance Commission, 47 percent of Illinois schools said they couldn’t guarantee that students would continue to receive in the spring semester awards they got in the fall.

Not surprisingly, this has all contributed to enrollment dings at most state schools. This academic year, for example, Eastern Illinois University saw its freshman class drop to 1,300 students, a 25 percent decrease over last year. Southern Illinois University Carbondale was down 24 percent. Neighboring public universities are only too happy to oblige. Schools like Iowa attract gifted students with scholarships but still earn more off them than they would from residents. And some colleges, such as the University of Missouri, show students how they can become eligible for in-state tuition after a year. “Ten years ago, no one [from Highland Park] went to Missouri,” Morrison says. “Now we send 10 to 15 students a year. Since the economy tanked, even families that can write a check aren’t as keen to do so.”

Then there’s the question of the value students are getting for their tuition. At Urbana, Illinois’s budget strain has resulted in a salary freeze for faculty and staff, as well as the departure of tenure-track professors. “We are under huge stress, and Rome is burning around us,” University of Illinois president Timothy Killeen told faculty at a meeting

in November.

With stopgap funding of $535 million for the current academic year (down from $662 million the year before), Killeen and U. of I. trustees in November backed a bill that would restore funding for the system to the 2015 level for five years. In return, the schools would commit to holding tuition and fee increases for in-state undergraduates to no more than the inflation rate and to using 12.5 percent of state funding for financial aid.

Still, there’s an age-old reason students leave the state, regardless of cost. Says Blumberg: “I liked the idea of being a little further away from my parents.”

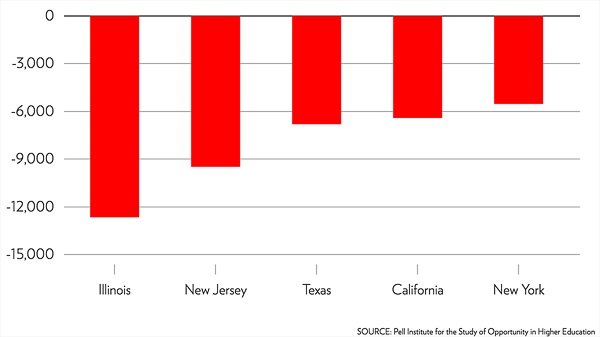

Who’s Bleeding the Most Students?

Illinois had the highest net migration of college freshmen to other states’ public schools in 2014 (the latest year for which figures are available). While 3,300 students came to Illinois from elsewhere, almost 16,000 fled. California lost about as many students but saw a bigger influx—9,500.

Comments are closed.