Albert Goodman, a descendant of the original Goodman Theatre benefactors, thought he had landed the “tall, thin beauty” his dating profile said he was seeking when he married April Summers in 1995. However, he soon discovered that she had invented much of her past, including her multiple degrees and professional licenses. Summers and her adoptive father had been hoping to soak Goodman for funds and even persuaded him to invest more than $100,000 in a property in Bartlett that they wanted to purchase. But when Goodman ended the marriage in 1997, Summers was unhappy with the divorce settlement. So the jilted ex sought revenge, as Nancy Millman chronicled in the 1999 Chicago story “The Heir, His Wife, and the Hit Man”:

According to court transcripts, Summers told her friend that her ex-husband was “worth $12 to $18 million,” and “whoever would kill him would receive part of the money.” Alarmed when Summers delivered to him a package with a photo of Goodman, his house and car keys, alarm code, and financial documents, the friend notified police.

On the evening of August 10, 1998, police say, in the McDonald’s parking lot across from Wrigley Field, Summers entered a van wired for audio and video surveillance by the Chicago police. There, police say, she handed over a down payment of $1,000 in cash to the supposed hit man — who in reality was undercover police officer Peter Bukiri.

Summers was tried for solicitation of murder in 2000. She was found guilty and sentenced to 30 years in prison. As for Goodman, he still serves as the honorary chairman of the Goodman Theatre and, along with his mother, largely financed its remodeling in 2000.

Read the full story below.

The Heir, His Wife, and the Hit Man

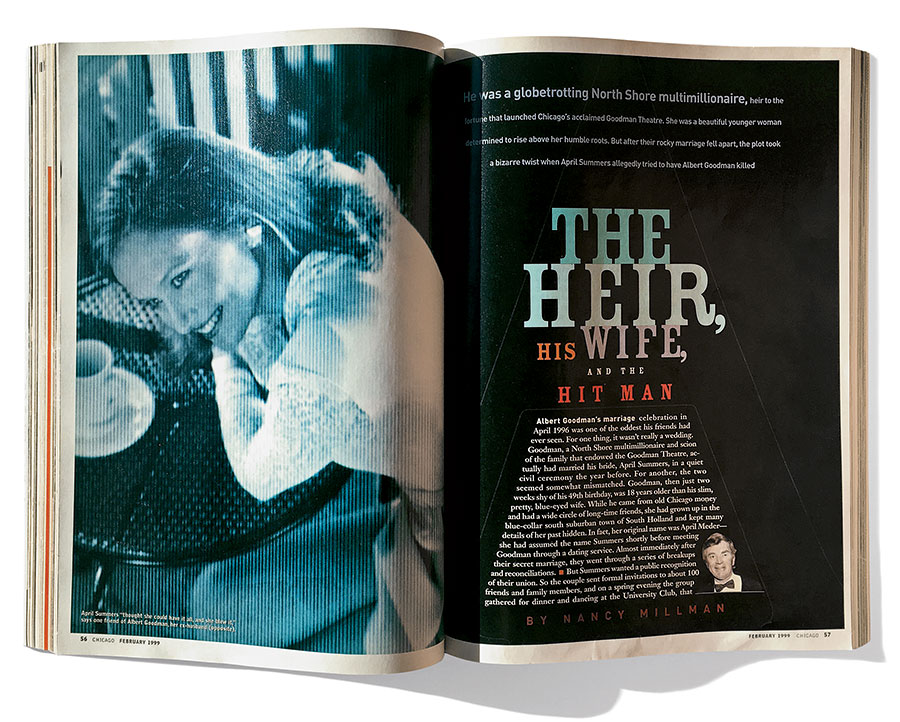

He was a globetrotting North Shore multimillionaire, heir to the fortune that launched Chicago’s acclaimed Goodman Theatre. She was a beautiful younger woman determined to rise above her humble roots. But after their rocky marriage fell apart, the plot took a bizarre twist when April Summers allegedly tried to have Albert Goodman killed.

Albert Goodman’s marriage celebration in April 1996 was one of the oddest his friends had ever seen. For one thing, it wasn’t really a wedding. Goodman, a North Shore multimillionaire and scion of the family that endowed the Goodman Theatre, actually had married his bride, April Summers, in a quiet civil ceremony the year before. For another, the two seemed somewhat mismatched. Goodman, then just two weeks shy of his 49th birthday, was 18 years older than his slim, pretty, blue-eyed wife. While he came from old Chicago money and had a wide circle of long-time friends, she had grown up in the blue-collar south suburban town of South Holland and kept many details of her past hidden. In fact, her original name was April Meder — she had assumed the name Summers shortly before meeting Goodman through a dating service. Almost immediately after their secret marriage, they went through a series of breakups and reconciliations. But Summers wanted a public recognition of their union. So the couple sent formal invitations to about 100 friends and family members, and on a spring evening the group gathered for dinner and dancing at the University Club, that Gothic Loop meeting place for many of Chicago’s select. Goodman’s friends, who tend to be worldly and cynical sorts, were astonished when Summers appeared in a spectacular wedding gown. Then she handed a piece of music to the bandleader and launched into a declaration of her vows in song. “I want to get lost with you,” she warbled. The guests huddled in sympathetic embarrassment for Goodman, who looked on meekly. “She thought she was such a great songstress,” recalls Goodman’s friend Tom Phillips. “We could barely contain our laughter.

The marriage, indeed, didn’t last and swiftly spun off into recriminations, accusations of violence, and divorce. Worse, police have charged that last August, almost a year after the divorce became final, April Summers tried to hire a hit man to kill her ex-husband. Though her alleged motive is unclear, Goodman’s lawyers speculate Summers believed that without Goodman in the picture, she stood a chance of influencing his wealthy mother to give her money and property she was denied in the divorce settlement.

Summers has pleaded guilty in the case and neither she nor her lawyer would comment. In a brief, polite telephone message, Goodman also declined to comment. Today, he has a new girlfriend — an athletic beauty from Puerto Rico — and he’s trying to put the tumultuous marriage and the shock of being an apparent murder target behind him. He has embarked on an extended trip to Nepal and other stops in Asia. Summers, meanwhile, is working with one of the city’s top criminal defense attorneys, Thomas Breen, to prepare for trial at a still undetermined date. Conviction for the crime would carry a minimum sentence of 20 years in prison.

The story of how a brief May-December romance turned into a web of contentious legal battles and a pending murder-for-hire charge is grounded in a clash between two worlds. Goodman, trusting and somewhat sheltered, relishes the life of a rich North Shore man of the world. Not accustomed to being accountable to anyone for his schedule or expenditures, he resented being hounded by his ambitious wife about business and personal matters. Summers, who has suffered from psychological problems, appears to have been desperately intent on rising above her life in South Holland where she grew up with her divorced mother in a 1950s split-level on a cul-de-sac a few blocks from Thornwood High School. “She thought she had the golden goose,” theorizes Phillips. “She thought she could have it all, and she blew it. That’s why she’s so mad.”

I am a very lucky person. The successful financial management that I have given to my portfolio of investments has taken most of the stress out of my life. This has left me looking and feeling ten years younger than I really am.

Albert Goodman

Great Expectations member profile

Albert Ivar Goodman was probably naïve to hint at his wealth this way to prospects at Great Expectations, the dating service. In his member profile, made available to women in search of a date, Goodman also mentioned his love of travel, his “Trinidad Nine Hundred Yankee” airplane, and the four trips around the world he had taken. But that’s just how he is, say his friends.

A gray-haired man of medium build, Goodman dresses in threadbare sweaters, drives a dowdy Oldsmobile, and collects friends from all walks of life. “You’d never know he was filthy rich,” says one of his business associates. But, he adds, Goodman never lets anyone else pick up a check.

The Goodman family fortune was made in the lumber business in the north woods of Wisconsin and in Chicago starting with Albert Goodman’s great-great-grandfather Owen Bruner Goodman. One of Albert’s great-uncles, William Goodman, married Erna Sawyer, a Wisconsin senator’s daughter. It was in honor of their only son, Kenneth Sawyer Goodman, who died of influenza while serving as a lieutenant at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, that the original endowment for the Goodman Theatre was donated in 1925.

The family’s involvement in lumber seems to have ended with the death of William Goodman in 1936 at age 87. His 2,600 shares in the company were part of his almost $2-million estate, more than half of which went to his widow. In his will were charitable bequests to Chicago hospitals, the Orchestral Association, and the Chicago Historical Society. Albert Goodman’s father, Robert B. Goodman, a nephew of the lumberman, also was a beneficiary in the will. The family collected art and antiques, and when Erna Sawyer Goodman died in 1943, the collection of paintings and historic pewter was donated to the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Goodman family was well known for its philanthropy because of the famous theatre, but Albert Goodman’s mother’s family was the source of the contemporary family fortune. His father, a chemical engineer, married Edith Marie Appleton, the daughter of Albert Ivar Appleton, an immigrant from Sweden who in 1903 had started a company that manufactured electrical equipment. The Appleton Electric Company grew into a powerhouse, with a factory in Chicago and executive offices in Skokie. In 1982, the St. Louis–based industrial giant Emerson Electric bought Appleton for an undisclosed sum, dropping tens of millions of dollars into the laps of family members.

The marriage between Albert’s parents did not last and was one of several for Edith Appleton, who now uses her maiden name. Albert was her only child.

Home for Albert was a stately white-frame colonial-style house with green shutters in the exclusive Indian Hill Estates section of Wilmette, where he lived with his mother and, sometimes, a stepfather. He attended New Trier High School and graduated in 1965, a baby boomer launched into the world at the dawn of the era of long hair, flower power, and the counterculture.

Goodman earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in business at the University of Southern California. Today, his primary business interest — aside from managing his extensive investment portfolio — is real estate. In the late 1980s, he established a firm, A. I. Goodman Realty in Wilmette, that specialized in representing buyers of residential real estate on the North Shore. Tom Phillips, today the firm’s lone employee, says Goodman’s day-to-day involvement in the business is not extensive, because much of his time is spent traveling. “He is aware of what is going on in all the deals, and he pays the bills,” Phillips said. Court documents filed by Summers in the divorce case state that Goodman earned taxable income of about $600,000 a year, and it appears that most of that income was derived from his investments.

Albert is the only member of the Goodman family remaining in Chicago (his father remarried and has another family in California). He stayed active with the Goodman Theatre as vice-chairman of the board and as a generous donor, other board members say. In September 1997, the Goodman Theatre announced that two new theatres being built in the North Loop would be named the Albert Ivar Goodman Theatre and the Owner Bruner Goodman Theatre in recognition of the latest gift — an undisclosed amount — from Albert and his mother.

Since his college days at USC, Goodman has maintained much the same lifestyle. Here’s how he described what he likes to do in his self-profile for the dating service (the profile, like that of April Summers, became part of the court file in the divorce case): “You will find me in a great mood when sharing time with my friends. They are a humorous and trustworthy crew, and they can be found from coast to coast and in Europe, too.” Goodman likes to organize and pay for exotic trips for groups of friends, sometimes on the spur of the moment. He is known for frequently throwing parties, sometimes with blues or jazz bands, and always with ample food and drink. All of his family’s homes and retreats are open to his friends, say his associates. The Wilmette house where he grew up is often the setting for parties. So, too, is his mother’s house in Northbrook, on a stunning private wooded lane dotted with suburban mansions. The Sip and Dip, as the Northbrook house is called, has a swimming pool, a tennis court, bowling alleys, and a playhouse for visiting children.

Another popular hangout for Goodman and his friends is the family-owned hunting lodge in Eagle River, Wisconsin. In a spectacular setting near Butternut Lake in the north woods, the lodge has two buildings that together sleep more than 20 people. A cook and a staff of young women from the area look after the guests. It is not unusual for Albert to fill his plane with a group of his buddies and take off from the Waukegan airport for a long guys’ weekend at the lodge. During the summers, groups of friends with their spouses and children are invited for weeks filled with water-skiing, fishing, hiking, and cookouts. “He’s always been this way, very generous,” says David Cleland, who has known Goodman since junior high school. “He never had any brother and sisters; he always just had his mom, and he likes being around people.”

I enjoy teaching the tremendous values of compound interest over time and help anyone set up IRAs and mutual funds. People just aren’t told what they’ll need by retirement and how to get there, so we educate them.

April Meder

Great Expectations member profile

When April Summers, then still going by her maiden name of Meder, signed up with the dating service Great Expectations in 1993, she cited selling financial products as one of the things she liked to do. Based on her record in high school, she clearly had the talent. Next to the photograph grouping her with top seniors in the Thornwood class of 1983, April Meder had the longest list of activities and honors of the group: Mathletes, the competitive math team; National Honor Society; academic excellence awards in math, science, and English; speech team; Daughters of the American Revolution good citizen award; class salutatorian; band; pep club; cheerleading; and more. “She was a strong, assertive girl,” remembers Kathy Shannon, who has been a librarian at the school for 27 years. “I can imagine her thinking, ‘I’ll show that SOB’ about some guy.”

By the time Summers had transformed herself from a chubby-cheeked high schooler into a thin and stylish career woman and paid the $1,000 fee to join Great Expectations for a year, her life had taken some mysterious turns. In completing her dating-service questionnaire, for example, she couldn’t decide whether to present herself as a “sports industry executive,” which she did in one version, or as a financial services advisor, as she did in another. She wrote that she had a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences and two years of graduate school, had never been married, and was a licensed agent in real estate, insurance, lending, and securities.

Much of this proved to be false. She did attend Bradley University in Peoria on an academic scholarship for the 1983–84 school year and later transferred to Indiana University in Bloomington, which she attended from the fall of 1986 to May 1989 without receiving a degree. But according to the Illinois Secretary of State’s office, which registers licensed securities agents, Summers never had a license under her maiden name or her assumed name. Ditto with the state’s office of banks and real estate, which registers licensed agents: no record of April Meder or April Summers as a past or present agent. April Meder did have a license to sell insurance until it was canceled in April 1995 because she did not renew, said a spokeswoman for the state Department of Insurance.

The divorce decree that ended the Goodman marriage indicates that Summers had had an earlier marriage that was annulled. Other documents in the divorce case allege she had used at least three different names and ten addresses in the five years prior to marrying Goodman. No information about Summers’s first marriage, or the name of her husband, could be documented.

At Great Expectations, director Patty Gill says this case has brought to her attention the necessity for background checks on clients. Gill, who has operated the service only since last July, says the previous management did not investigate the claims that clients made about themselves. “We’re looking into finding a company that could do background checks, at least to investigate whether there is any criminal record,” Gill says. (Because Meder did not have a criminal record, such a check would have done little good in her case.)

Unarguably the most mysterious element in Summers’s post-college life is her relationship with Robert Schnee, who adopted her as his daughter the year before her marriage to Goodman. Schnee, a trim, pleasant-looking man with brown hair and wire-rimmed glasses, is only six years older than his adopted daughter, and lawyers for Goodman contend in court papers that he is her boyfriend. Schnee, who has described himself as a driver for United Parcel Service, would not comment.

Goodman’s lawyers say they saw proof that the adoption was legal, but are in the dark about why it took place. “April said, ‘I would never live in the same house with a man I wasn’t married to or if he wasn’t my father,’” says Craig Hammond, Goodman’s divorce lawyer. “April has never admitted to sex with Bob Schnee. But she already has a mom and dad who are living.”

With the adoption came the switch to the made-up name Summers, and at some time she acquired a second social security number. Explaining all this during the divorce proceedings, Summers told Goodman’s lawyers that she had needed to change her identity. In college at Indiana, she claimed, she had helped campus police in a drug bust, and she felt her safety was threatened as a result.

An official from the Indiana University police force, Lieutenant Steven Fiscus, confirmed the same information to Chicago that he had given in a statement in the divorce case — that April Meder was not part of any enforcement action by police at the university.

After her divorce from Goodman was final, Summers embarked on a new career as an actress and model. She posed for a composite of sexy photographs to help her land jobs through the Lily’s Talent Agency in Chicago. “She was a little up there in age to be a fashion model,” says Lily Ho, the president of the firm. “Those girls are much younger. She was suitable for character models in commercial print, and we sent her on some look-sees.” But Summers, who was still using her married name, Goodman, was never hired, says Ho, whose firm represents some 2,000 actors and models.

I am looking for that career woman in her early to mid thirties who is successful, but who is looking for something more to life. I am looking for that tall thin beauty who after a year of travel and marriage will work with me to make a family of two or three children.

Albert Goodman

Albert Goodman was married for the first time at age 34 to a woman of Chinese-Thai descent named Sunee, whom he had met while traveling in Thailand. The two were married in Bangkok in April 1981, and then moved to Los Angeles, where they lived for about three years. Then they headed for the East Coast and a 22-acre estate Albert owned called Little Old Town Hill in Newbury, Massachusetts. After a few more years, Albert and Sunee returned to Wilmette, where they lived in the house in which he grew up and which is owned by his mother.

“Sunee was a very demure and quiet, sweet kind of person,” recalls David Cleland, Goodman’s long-time friend. The first Mrs. Goodman didn’t try to fit in with the social scene at the North Shore parties that her husband threw every three or four weeks, says Cleland, who works as a firefighter and paramedic in Evanston. “She was pretty much a clean liver,” he says. “I don’t think she ever drank at all. She just kind of put up with the parties because that was Albert’s thing.”

The couple never had any children, and one of Goodman’s friends thinks that may have been one of the reasons the marriage didn’t last. Sunee and Albert divorced in 1990, and Goodman was able to negotiate the settlement without disclosing his assets to his wife of nine years. The agreement was reached against the advice of Sunee’s lawyer. Sunee was to receive maintenance of $60,000 a year for seven years, the house in Massachusetts, and five of the acres of surrounding land. (Sunee Goodman could not be reached for comment.)

As Goodman neared 50, his friends say, he was eager to become a father. And though it may seem odd that a rich, eligible bachelor would look to a dating service to find the girl of his dreams, Craig Hammond says Goodman didn’t see it that way. “I’ve met lots of wonderful people through dating services,” Goodman said, according to Hammond.

I’m comfortable in any environment: I’m a sophisticated, intelligent lady for high-powered business meetings or charity events; I’m a fun and friendly girl for sporting events and casual get togethers with friends. I have a wonderful up-beat personality, strong ideals and morals, and an always loving heart. Try me. I could be your best ‘return on investment’ yet!

April Meder

At the time that Summers and Goodman hooked up for their first date through Great Expectations, she was 29, according to her dating service profile, and living in suburban Palatine. Goodman was 47, and engaged in his regular combination of traveling, looking after his investments, and dabbling in real estate. On that first date, January 25, 1995, Summers said she was a developer, and Goodman indicated that he was interested in investing in real estate, according to one of Goodman’s lawyers. Summers took him to see some property that she was trying to acquire, a 24-acre parcel of vacant land in Bartlett, a town about 25 miles directly west of Chicago. Summers and Robert Schnee had a contract for an option to buy the land for about $800,000, and Summers told Goodman she was putting together a limited partnership and had other investors lined up, says Sherman Magidson, one of Goodman’s lawyers. She hoped to develop the land into a sub-division in the rapidly expanding corridor west of O’Hare International Airport. Summers immediately persuaded Goodman to invest $25,000, Magidson says. The property’s owners did not recognize Summer’s option until Goodman invested in the deal. “No one else ever put up a nickel,” one of Goodman’s lawyers says. This piece of property became the central issue of contention in the relationship between Summers and Goodman.

During their five-month courtship, Goodman invested about $95,000 in this so-called limited partnership, which, according to Magidson, actually had no investors besides Goodman. Furthermore, the lawyer contended in court proceedings, some of the money that Goodman was providing was not used for the deal, but went directly to Summers and to Schnee, with whom she lived at the time.

Summers’s focus on money seemed obsessive to many of Goodman’s friends, but they understood her initial appeal. “Albert was impressed by the fact that she presented herself as this astute businesswoman,” Phillips recalls.

The 1994 Pontiac that Summers drove — which was registered to Schnee — had the license plate MONEE DR. She boasted to Goodman’s friends of her prowess in the financial counseling of fellow parishioners at the enormous Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington.

Though several of Goodman’s close friends found Summers attractive and somewhat friendly, they warned him to be careful, to check her out. “She seemed shallow and concerned only with herself,” says Cleland. “She talked about money all the time — how she had these development deals and was going to make a killing in real estate.” (It is not clear how she supported herself before she married Goodman.)

Despite his friends’ counsel, and without telling anyone, Goodman married Summers in a courthouse ceremony in Wheaton on June 30, 1995. That afternoon, according to Magidson, Goodman dropped his bride off at Schnee’s house and flew with his father, who was visiting from California, to the lodge in northern Wisconsin.

Over the course of the summer Goodman poured more and more money into the contract on the Bartlett property, including $65,000 to buy out an investment Schnee claimed he had made in the partnership. Though Summers now was married to Goodman, she had a joint checking account with Schnee and spend an average of two nights a week at his home, Magidson said in court proceedings.

I am in no hurry. Let us have fun. It’s good to be alive.

Albert Goodman

Goodman’s hopes for a free and easy relationship were dashed once the two were married. He began to think that he was being taken advantage of — if not defrauded — by his wife and her adoptive father, Magidson says. As a result, Goodman wanted to get out of the contract on the Bartlett property. “I started hearing these stories from Albert that she constantly made demands about this parcel of land,” Phillips recalls. “He ended up sinking all this money into it, and she wanted to be part of the action. She wanted to get her finger into it. She never let up, and it really got to him.”

But instead of canceling the real estate contract, Goodman filed for an annulment on August 29, 1995, just two months after they had gotten married. Though the couple were spending little time together, Summers — by now going by the name April Goodman — would not agree to the annulment, and Goodman let it ride. He lived as he pleased, taking off on trips to Florida, Puerto Rico, California, and the Pacific Islands without his wife and continuing in his role as host for his wide group of friends.

Meanwhile, Summers started nagging Edith Appleton about management of her fortune, Goodman’s lawyers said in court. Summers also wrote her husband a long, rambling letter telling him that Appleton should place much of her money in Summers’s name. Alternatively, Summers suggested, Appleton should create trusts for the children the Goodmans planned to have, and make Summers guardian so that Edith Appleton “wouldn’t have her fifty-million-dollar estate so heavily taxed,” Magidson said in court. When the new Mrs. Goodman broached the subject to Appleton personally, the 76-year-old lady replied, “We wait until the children are born, dear,” according to Goodman’s lawyer Craig Hammond. Edith Appleton did not respond to requests for interviews for this article.

Still, Goodman couldn’t stay completely away from his wife. On numerous occasions, he took her with other friends to his lodge in Wisconsin and to society events in Chicago. Even Robert Schnee became part of the Goodman entourage and was included in parties both in Chicago and at the Wisconsin lodge. “We like Bob,” says Cleland. “We always say, ‘What about Bob? Why isn’t she with Bob?’ We don’t know exactly what he is to her, but he seems like the guy who’s always been there backing her up, bucking her up. I always thought he was a normal, stand-up kind of guy.”

By night: an affectionate companion, capable of giving and sharing in addition to receiving, plus intimacy and passion, and possibly a ‘partnership’ in love and marriage.

April Meder

Less than two months after Goodman and Summers staged their elaborate wedding party at the University Club, they were locked in an ugly battle.

Though Albert’s petition for annulment was still pending, the Goodmans would spend nights together at the Wilmette house when he was not traveling with friends. On June 11, 1996, the couple returned home from dinner at Hackney’s, the local hamburger joint, and Summers told her husband she believed she was pregnant. The pregnancy was never documented, Hammond says.

After dinner, the couple spent an hour or so talking and listening to music, and then Goodman went upstairs to get undressed for bed. According to court testimony, as Goodman slipped under the covers in the couple’s bed, his wife asked him to move to another bedroom. “I just wanted him to spend time in the other room,” Summers said in court testimony. “You’re not supposed to have sex when you’re first pregnant.” Summers said that Goodman, who had been drinking throughout the evening, lost his temper. When she followed him out of the bedroom into the hallway, she testified, he tried to push her over the railing, one story above the entry hall.

Goodman remembered the incident differently. The couple were arguing about their relationship and about the never-ending problem of the Bartlett property, his lawyers say. Godman believed, but was reluctant to tell police, that his wife had tried to push him over the railing. “‘This is more than a woman who is pissed off,’” Magidson remembers his client saying. “‘I’m terrified she’s going to try to kill me or us.’”

Goodman left the house on foot, and Summers called the Wilmette police. Goodman was arrested a block from his home, charged with domestic battery, and taken to the Skokie lockup, where he spent the night.

A judge signed an order of protection to keep Goodman away from his wife, and he moved to his mother’s house in Northbrook. A few weeks later, Summers filed another domestic battery complaint against Goodman, based on an incident that had taken place at his mother’s house. The two complaints were consolidated into one case, and Goodman appeared in a bench trial before Cook County municipal court judge Robert Nix in January 1997. After hearing testimony for two days, Nix found Goodman not guilty.

The filing of battery charges escalated the tensions between the couple. Court documents show that the day after Goodman was charged, his wife took a $10,000 cash advance against his platinum MasterCard account. Two weeks later, she charged two $5,000 advances on the same card at the Grand Victoria, the casino in Elgin, according to court records. Then Goodman used an eviction threat to force her out of the Wilmette house, arguing that he feared she would sell or damage artwork and other treasures there.

Summers still wouldn’t give up on the Bartlett deal. Earlier in the year, Goodman had exercised the option to buy the 24-acre plot of land and had paid $780,000 to bring the total purchase price to about $1 million. Before the closing, Schnee and Summers, whose names were on the original document for the Bartlett property, signed over their rights to the land, Goodman’s lawyers say. Goodman and his mother were the sole investors and placed the property in a land trust. At the closing of the sale, Summers appeared unexpectedly at the title company’s office and insisted that she was entitled to a commission on the final sale. The commission had to be put in escrow so the closing of the sale would not be held up, Goodman’s lawyers say, but Summers dropped her claim because she could not provide documentation.

Having failed to persuade her husband to cut her in on the deal, Summers went to work on Goodman’s mother, says his lawyer Magidson. On July 31, 1996, Summers drove to Northbrook and dropped in uninvited on her mother-in-law. A lawyer representing Summers and Schnee had drawn up a contract under which a company they had founded would buy the land from Goodman and his mother. “During the course of her social visit, which involved drinking large quantities of wine, my wife persuaded my mother to execute the contract for the purchase of the Bartlett property for $20,000 less than we had invested,” Goodman said in a court affidavit.

Goodman immediately got an order of protection to keep Summers away from his mother’s house. The contract was not valid, Goodman’s lawyers say, because Mrs. Appleton did not have the power to direct the land trust. To this day the property has not been developed.

By the time divorce proceedings began in earnest, in September 1996, Summers was exhibiting signs of instability, Goodman’s lawyer says. One night, while her husband was a meeting of the Goodman Theatre’s board of trustees, Summers drove to the theatre and demanded to be admitted, Magidson claimed in court. She became agitated and eventually hysterical when refused, and security guards had to remove her, while her husband escaped through a back exit.

And in the divorce litigation itself, the many versions of her stories perplexed the lawyers. “Albert encouraged her to get treatment,” Hammond says. “He was concerned about it whether or not they stayed together.”

Just before the scheduled trial date of June 24, 1997, Summers’s divorce lawyer, Michael Minton, told Goodman’s lawyer that doctors were “concerned that the stress of the trial may cause April to commit suicide,” according to court documents. “April Goodman is a very sensitive lady,” psychologist Robert B. Shapiro wrote in a letter to her lawyer, found in the court file. “That sensitivity, however, is currently being experienced in a painful way. Her depression is prominent and her anxiety is excessive. Because she is so wrapped up in herself, it has become nearly impossible for her to have a realistic perspective about her life and the events in her life.” Shapiro recommended hospitalization, and the trial was postponed until September.

During Summers’s hospitalization at Columbia Lakeshore Hospital, her psychiatrist, Louis J. Kraus, wrote to Goodman that she was diagnosed as having bipolar disorder. “She continues to show depressive symptoms and associated symptoms consistent with a resolving manic state,” he said.

The divorce was finally settled on September 19, 1997. Court documents do not disclose the financial agreements. Goodman’s lawyers declined to comment on the details, and Summer’s lawyer did not return calls. Hammond says that Summers continued to contact Goodman through the winter and spring of 1998. “She called and said she was broke, and he gave her several thousand dollars” early in the spring, Hammond says. “She called a month later and he gave her money again. The last time she called, he told her no. A month later she’s arrested.”

Sometime during the summer of 1998, police say, Summers asked a male friend if he could find someone to kill her husband. The police are keeping the identity of her friend under wraps. According to court transcripts, Summers told her friend that her ex-husband was “worth $12 to $18 million,” and “whoever would kill him would receive part of the money.” Alarmed when Summers delivered to him a package with a photo of Goodman, his house and car keys, alarm code, and financial documents, the friend notified the police.

On the evening of August 10, 1998, police say, in the McDonald’s parking lot across from Wrigley Field, Summers entered a van wired for audio and video surveillance by the Chicago police. There, police say, she handed over a down payment of $1,000 in cash to the supposed hit man — who in reality was undercover police officer Peter Bukiri.

Summers was arrested later that evening as she left an acting class on the city’s North Side. She has been charged with solicitation of murder for hire. She has pleaded not guilty and is free on $150,000 bond. At her bond hearing, her lawyer, Thomas Breen, told the judge that Summers’s statements had been misunderstood. Breen cited his client’s bipolar disorder and her need for treatment. “She was merely stating her dislike for her former husband, for actions committed by her former husband,” Breen argued.

But prosecutors said in court that the former honor student was intent on finding someone to kill her rich ex-husband, and that the tapes will prove their case. Goodman himself is concerned enough that he has moved his mother to a friend’s home in California, and he is keeping his distance from the North Shore. “I’ll be glad when this is over, and I can come home again,” he said in a telephone message that sounded as if it came from a faraway land.