“How does Max cope with his anxiety?” my son’s psychiatrist asked me the summer Max turned 9.

“He draws a circle on the gym floor and sits in the middle, and then all the other kids have to stay outside of the circle.”

She considered this. “We’d like him feeling better than that.”

No shit, I wanted to say. But I just smiled ruefully because, well, here we are, and what can you do? And obviously I wanted her to know I’m a good mother.

I don’t remember a time that I wasn’t living with an anxious person. When I was a kid, my mother was always worried. If we were on a family trip, she’d wait until we were about an hour outside of town and then start wondering aloud if she’d locked the door or turned off the curling iron. And then she and my father would tersely debate whether or not to turn our Oldsmobile around, and I could feel the tension rising, rising, as I gripped the back seat’s velour upholstery. Later, when I was an adult, she once told me, “Today I will be practicing HALT. It stands for ‘hungry, angry, lonely, tired.’ I will alert you when I feel one of those things.”

Perhaps it was this sort of training that prompted me to marry (and later divorce) an anxious man, the kind of man who needs to take a Xanax before entering a Trader Joe’s. Which, in theory, is not an entirely irrational reaction to Trader Joe’s, but this is just one example. You’ll have to trust me that the others paint him as less adorably neurotic.

I’ve considered the possibility that there are two types of people in the world: the anxious and those who take care of them. I’ve been addressing other people’s anxiety for so long that I’ve become infinitely reasonable, flexible, and accommodating, and so, really, it should not have been a surprise when I found myself the mother of an anxious child. It was the ultimate promotion.

When Max was 3, after I’d divorced his father, the two of us moved to Chicago from Oregon, where I’d been working on my master’s in creative writing. Max was a sweet kid who loved to dance and jump around at the park and read stories about animals. I took him on a lot of hikes when we lived in Oregon, first carrying him on my back and later holding his hand. I remember fresh air and clear skies and rocky paths and have a mental picture of him toddling down a slope of tall grass, laughing. I don’t remember him being anxious then, but surely he must have been. Or at least the seeds were there.

We settled in a two-flat in North Center, and as I assembled his bookcases, I was filled with a lot of glossy ideas about all the high-culture things he would get to do as a kid growing up in the big city. Me? I grew up in Rockford, which was fine, especially if you like strip malls, but not really an exhilarating place that entire novels were written about. Obviously Max and I would expand our minds at all of Chicago’s museums. Most likely we’d become members of Lincoln Park Zoo — a lot of my friends from college already were. By the time he was 5, he’d know about feminism, systemic racism, the patriarchy, genderqueer, and genderfuck, and he’d be eating sushi and appreciating musical theater and possibly learning to sail.

If I’m being honest, I was very smug.

Max started preschool in Roscoe Village, and the very first week, his teacher called me to report that he was under a bush. I was confused. What was I supposed to do about it? I was at work. I remember hanging up the phone baffled and then writing the whole thing off as one of those weird passive-aggressive preschool things, like when your kid has an accident and they literally send the shit-filled pants home in a plastic bag. Later I understood that the teacher had wanted me to think of this moment as the first real indication that Max wasn’t going to be easy, that he was going to be a kid with very little chill, that he was going to be the kid under a bush, or a table, or later walking out the classroom door and wandering the halls.

As Max got older, his anxiety got worse — slowly at first and then sort of all at once. We did try to do all of the Chicago things I’d imagined, but I quickly found that a crowded Field Museum would rattle him so much that he’d completely shut down, becoming sort of a zombie, and even when he was back in the car, cruising along Lake Shore Drive, it would take him a while to reenter himself. And then he’d be apologetic and embarrassed, and I’d feel terrible because he was only 5 years old, so what did he have to apologize for?

And then I’d worry.

When your kid has too much anxiety to do drop-off birthday parties or sleepovers or playdates with more than two kids, or when your friends raising kids who aren’t exceptionally difficult invite you to things like the Pride Parade or Burger Fest or the zoo and you know the amount of pep-talking it will take to get your kid there, and how as soon as you’re there, he’ll complain of a headache or a stomachache or clutch at you or not respond to the other kids at all — you worry. I chewed my nails over how small his world was going to be. Before going to sleep at night, I thought about how at home he was one person — funny, joyful, thoughtful — and how as soon as we left our apartment, no one saw any of that. And there was so much explaining. “Max is difficult,” I would say, but still it didn’t seem like people really understood the cost-benefit calculus involved in dragging him to something like a Phish show at Wrigley Field. (That was my ex-husband. Obviously I would never take an anxious child to see a band whose songs literally never end.)

Cities are inherently chaotic. That’s part of the magic. And anxiety is about control. About seizing control over your environment to feel calm. Max’s anxiety has made me think a lot about who the city is for. If you’re a kid who finds a lot of stimuli stressful — what then? Is the city just not for you?

I’m not ready to believe that. Max is 10 now, and I want to give him the coping mechanisms he needs to take advantage of everything Chicago, and the world, have to offer. So we see a psychiatrist until we get the medication right. We say no to street fests. We arrive at the Shedd Aquarium 15 minutes before it opens so we’re the first people in the door. We never go on weekends and holidays. We drive instead of taking the train. We limit the amount of time we’re going to be there and schedule breaks. It’s a pain in the ass, really, but that’s parenting, I’m told. That’s life.

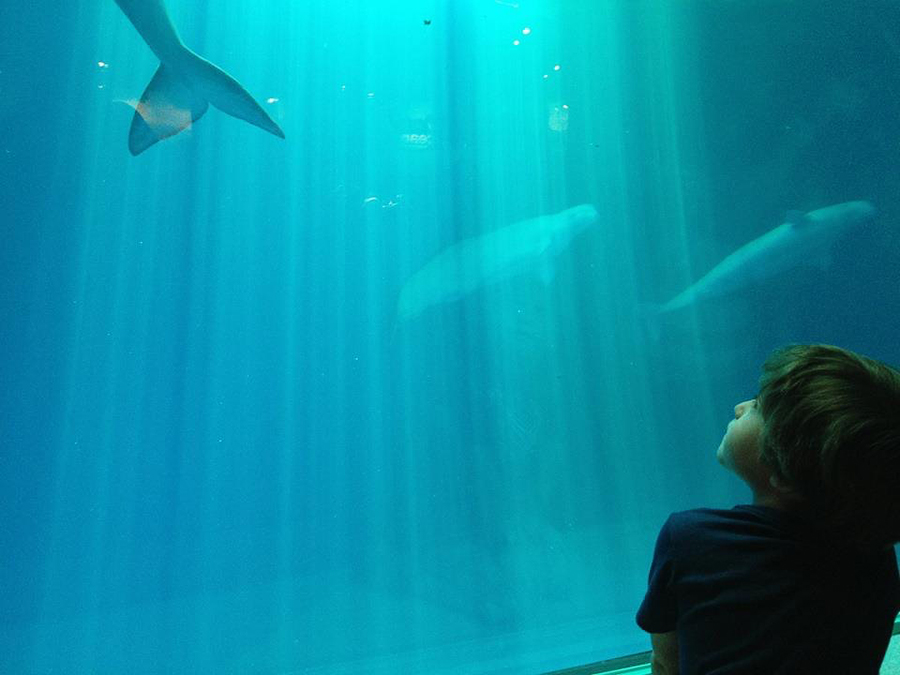

I have this photo of Max at the aquarium, staring up at a beluga whale that’s staring back down at him. A stream of light shines through the water, illuminating his face, and it’s a perfect picture, really, the kind you’d see in a magazine. And there it is. All the hassle and stress is worth it because you know I put that shit on my Instagram. But really, what Max has taught me about motherhood is this: The dreams change. They’re never what you think they’re going to be. But then you change. And there’s beauty in that too.