I graduated in 1967 from Sullivan High, a public school in East Rogers Park. My 50th reunion was this month at the Westin Hotel in Rosemont.

The location was just one reason I was reluctant to RSVP yes.

More important, I had a crummy time at the last reunion I attended, my 21st, in 1988 at the Deerfield Hyatt. (For reasons unknown, we had our “20th reunion” in 1988. Thus I refer to it as the 21st.)

I had maintained very few ties to my classmates. It wasn’t just a matter of geography—our children didn’t attend the same schools, as many of them settled in the suburbs whereas my husband and I remained in the city—but also a matter of personality. I saw high school as a ticket out of the life my mother led. I arranged my high school schedule so I could escape the building every day at 2 p.m. I worked about 30 hours a week as a cashier at the Jewel on Morse Avenue, and then I came home and studied, often into the early morning hours. I needed to be admitted to the University of Illinois in Urbana, preferably on scholarship, and I needed top grades to accomplish that. Even if I hadn’t worked, I would still have skipped extracurriculars.

I disliked that reunion for the same reasons I disliked high school: that sense of not quite fitting in, of being an outsider.

My husband, who accompanied me, had attended a grade school that fed into Sullivan, so he knew people—and he seemed more connected at that 1988 event than I. When it came time to sit for dinner that night in 1988, the cliques claimed their tables, and back came that dreadful where-should-I-sit-in-the-lunch-room feeling. I longed for an exit, brooding about a wasted evening, while most of my classmates hugged, laughed, and danced.

Why repeat that experience?

Last June I was invited to speak at Jewish Authors Night at Max and Benny’s in Northbrook. Nearly everybody in the deli’s private room was a stranger except for a few classmates who came up to greet me. We were so mutually delighted to see each other and to share memories that I came home and told my husband, “Let’s go to my reunion.”

Remembering how uncomfortable I felt at the last one, I stashed my reporter’s notebook in my bag thinking I might interview people: Hillary or Trump? DACA, 2020, NFL, health care. I even seriously considered recording my classmates on my iPhone as if I were a reporter rather than a participant—until my husband told me he thought that was a really bad idea.

We put the Cubs game on the radio en route to the event. I had been only half-listening, but I suggested we remain in the car until the inning ended. I was not eager for 1988 redux.

Entering the room, this reunion felt remarkably different. Fifty years changes faces, posture, gait, width, height. (The subject of hair requires its own post.) It also evens things out. In 1988, people were still in their late 30s and really worked at looking good; this time, most everybody looked the same degree of old. There were only a few people at the reunion who wouldn’t be offered a seat on the subway. I was wearing some cool jeans and sneakers, but I still looked 68.

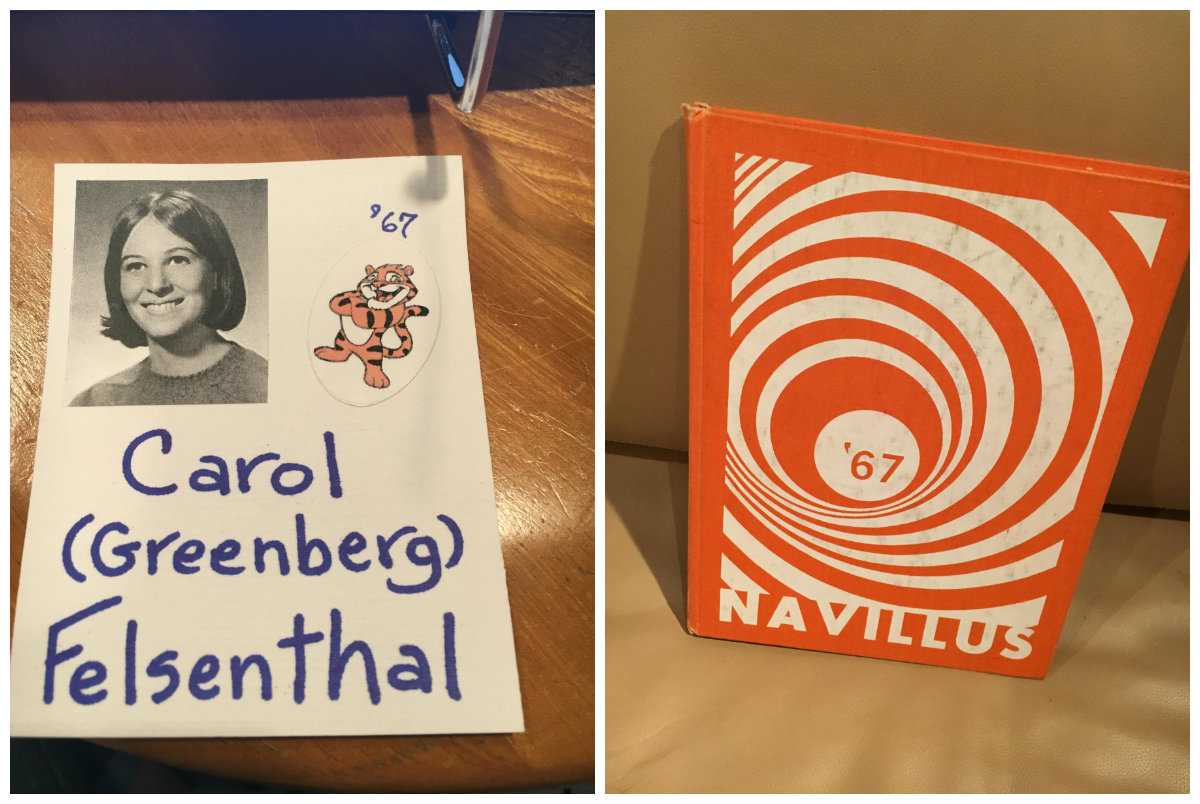

Though I had a momentary scare when I tried to sit down at a table and was told that those seats were “taken,” I somehow broke out of my shell. I studied the illustrated name tags hanging around everyone’s neck—for women they contained first name, maiden name (in parentheses), married name and yearbook picture. They made recognizing people I hadn’t seen in 29 or 50 years foolproof. To my surprise, I was having fun. I haven’t hugged so many humans since my mother’s funeral.

So here we were in 2017, 98 members of the class of ‘67. We seemed so connected, cohesive, talking to one another in a remarkably boast-free manner. If people brandished their cell phones to show off pictures of their children, grandchildren, or their last vacation, I didn’t see them. At 21 years, one-upmanship and other remnants of high school life filled the room. At 50 years, it didn’t matter if you were a corporate exec or a recluse, a retiree or a workaholic, a Ph.D. or a college dropout. All that mattered was that you had lived long enough to be there and had the means to pay $125 per person for a hunk of fried chicken and a quinoa patty that resembled the Gaines-Burgers I fed my dog in the 1970s.

At the 20th reunion, a bulletin board near the registration desk touted the accomplishments of just a few in our class. I was on it—one of my books had just been published or was about to be, and there was a copy of its cover or of a review or both. Although in high school I daydreamed about such recognition, that night I just wanted to go home.

Thirty years later, no brag board, but instead a death board, the achingly young yearbook photos of 25 classmates who have died. People lingered in front of it, but most had trouble deciphering the names in the dim light. The glow of their smartphone flashlights cast an eerie spirituality.

Then there was my high school boyfriend. We broke up shortly after I left home for college in September 1967. When I saw him in 1988, our exchanges were self-conscious and lifeless. Twenty-nine years later they were lovely—as if we had become dear old friends across decades of non-communication.

I had wanted to tell him something that night 29 years ago, but the atmosphere was all wrong. At 50 years, it was right and I described a comment that a teacher had hurled at me senior year. “He’s too good for you,” she said. I knew without asking what she meant. My boyfriend was a class leader, student council president, someone who cared about things outside himself. She saw me as a selfish grind.

I recognized then that the teacher was a jerk and her comment inappropriate, but it never lost its sting—until the reunion this year, when he replied to my story with one of his own. A woman who taught us both English, who had informed and lifted my taste in fiction, had stopped him after class. “I find it interesting that you and Carol are seeing each other because I thought that you preferred silly girls with no brains!"

“This is my last rodeo,” I had insisted to my husband as sat in expressway traffic on the way there. “I’ll never go to another reunion.” Walking to our car to drive home, I had slightly modified my take: “I think I’ll quit while I’m ahead,” I said to him, but to myself I admitted that I was taking with me some lasting memories of a night well spent. Who knows? In 2022 I might be ready again to revisit high school.