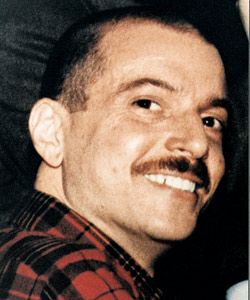

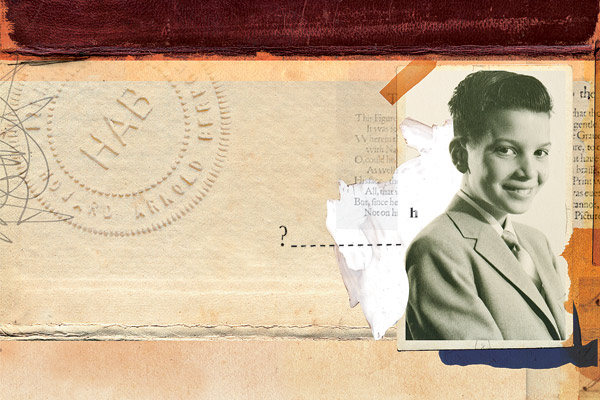

Berkowitz as a boy; a raised seal on the pages of his books identified them as from the “Library of Howard Arnold Berkowitz.”

Howard Arnold Berkowitz lived most of the last 17 years of his life in a high-rise studio apartment that afforded views of Chicago’s movie-set skyline, of the grid of streets below that stretch as far as the eye can see, and of vast, formidable Lake Michigan. He loved literature and philosophy, theatre and classical music, and his panoramic views of the city and the lake. He died from complications of AIDS, at 48, on Christmas Eve 1992.

His apartment complex, known as McClurg Court, includes elliptical twin glass towers that stand at right angles to each other in Streeterville between Ohio and Ontario streets. Howard’s apartment was situated on the 17th floor and at the southeastern curve of the northwestern tower. Two months before his death, I moved into the same tower, where I occupied a studio apartment facing north on the 22nd floor. If our days at McClurg overlapped, it was only briefly before Howard relocated to a hospice somewhere on the North Shore.

I imagine that for Howard, the fall of 1992 must have been hell, or something like it. When I think of his plight during those final months, I recall the symptoms described in Vikram Seth’s poem “Soon”: “My throat cased in white spawn / These hands that shake and waste.” In contrast to Howard, I myself could not have asked for better physical health during the fall of 1992: I was 28 years old and had spent the preceding summer teaching tennis in and around Chicago. With the tennis season behind me, I took my autumn exercise via six-mile runs along the lakeshore and kilometer swims in a sports-club pool. My enviable health, however, was strictly from the neck down. Mentally, I was fighting a battle of my own, my meager defenses being the gooseneck lamps that I kept buying—ultimately 11 altogether—to combat the darkness that descended upon the city, and upon my spirit, a little earlier each day.

Just as Howard was losing his battle against AIDS, I was losing my battle against what the writer William Styron called the “darkness visible.” In mid-November 1992, halfway through my first semester at Northwestern University School of Law, I resigned my position in the class. Exiled from the law school, and having few other social contacts in the city, I was largely confined to the loneliness of my McClurg studio, from which I sought escape via long walks either along the shore of Lake Michigan or up and down the Magnificent Mile. As Christmas approached, the city seemed locked in the sort of perpetual darkness that, as a child, I had imagined as descending in Icelandic winters. The holiday lights of Michigan Avenue did little to elevate my mood. On or about Christmas Eve, the day Howard died, I boarded a train in Union Station bound for Detroit, where I would spend the holiday with my family.

With the new year, I returned to my white box in the Chicago sky. I regained my job as a tennis instructor and began daily commuting crosstown between McClurg and the East Bank Club on an old Schwinn bicycle, a wool hat pulled low over my ears and my hands in leather gloves. I was taking life one day—indeed, one hour—at a time, trying to block out the previous year and to focus instead upon my current task: to strike a tennis ball so that it would travel with moderate speed, spin, and depth, and thus be fun and easy for the client to return. Then came the sunny, cold January afternoon, during this time of living obsessively in the present, when I walked my bike into McClurg and found the lobby momentarily transformed by the legacy of the late Howard Arnold Berkowitz: The entire floor, from glass entryway to the elevators, was covered with shopping bags full of books. Walking among them were two young men who had removed the books from Howard’s apartment and transported them to ground level. A woman, fashionably dressed in trench coat and heels, noticed my interest and told me that I was welcome to keep any of the books that I wanted.

Immediately as I began looking through the bags, I understood that I had stumbled upon something extraordinary. Almost all of the books were hardcover, and many of the works, whether bound in single or multiple volumes, were sheathed in protective casings. Virtually without exception, they were classics in mint condition, and some were reprints of first editions. Reaching at random as if for gifts from a grab bag, I would find literature by the likes of Shakespeare, Aristotle, Thoreau, Emerson, James, Proust, and Nabokov; psychological studies by Freud and Jung; collected stories of Eudora Welty and Isaac Bashevis Singer; biographies of Woolf and Dickens; important reference books, such as the eight-volume Encyclopedia of Philosophy; and histories, such as Edward Gibbon’s eight-volume The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and Winston Churchill’s six-volume The Second World War. It was a literary pot of gold at the center of the nuclear crater that was my life.

“See any you like?” the woman asked me. She told me that friends and family had taken some of the books, but many were left over. I also recall that she had found an institution that was willing to look at what remained, but it wouldn’t pay for their transportation. When I arrived, she was awaiting vehicles that would take the books away. I made a quick calculation, and although I worried about appearing greedy, I figured that I had nothing to lose.

“May I have all of them?” I asked.

She seemed surprised for only a moment, and then, appearing to make a quick calculation of her own, she agreed. The help of the two young men was again enlisted to return the bags via elevator to my one-room apartment. As this was going on, the woman offered to show me a few other items that had belonged to Howard and that remained in the building. She took me to his 17th-floor apartment, where bookcases lined one wall and a low bed remained in the middle of the room. She then escorted me to his basement storage bin, essentially a wire cage, where an assortment of albums, cookware, and additional books remained. I said that I would take all the items in storage—or more precisely, assume responsibility for them. All that I ultimately decided not to keep, I would be responsible for discarding. She arranged for me to have keys and access both to the apartment and to the storage bin for a few days, and then she was gone. Later, as I reflected upon her actions, I considered the possibility that she gave me the books not because she wanted to save time and money, but because she understood that they had been found by someone who might love them as much as their original owner obviously had.

* * *

Back in my apartment, I surveyed the scene. Bags of books were everywhere. They narrowed my thin hallway, making passage with my bicycle the proverbial camel’s trip through the needle’s eye. Other bags made stepping from the bathroom to the closet an exercise in Monty Python’s silly walks. In the kitchen they covered the countertops and floor, blocking access to the cabinets and fridge. In the main part of my studio, only my futon was left uncovered with bags. It was crazy, but what beautiful book was I going to discard first—the biography of Dickens, the speeches of Abraham Lincoln, or the reprint of the first edition of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, its original price, “one dollar fifty,” quaintly printed on its spine? With euphoric disbelief, I spent a few hours exploring my windfall. There was not a single book that was not important, not a single book that I didn’t love. Howard had expressed his love for these books by acquiring an instrument that, when pressed on a page, left a raised seal; inside each volume, the notation read “Library of Howard Arnold Berkowitz.” I ran my fingers over the colorless words, as though they were Braille. I knew that Howard must have invested many hours of thought in choosing the books, and many thousands of dollars in procuring them.

Within a day or two, I returned to Howard’s apartment to take another look at his bookshelves. They had been made from thick, heavy slabs of wood that retained a rough, natural quality. The bookshelves were not fancy, but they were beautiful. Howard’s bed, which lay flat on the floor in the middle of the room, was framed by those same sturdy wooden planks.

I decided to capture the bookcases for my apartment, though for a reason I can’t quite remember I had to shorten them with a saw. Because my job as a tennis pro often kept me at the courts well past regular business hours, I started my sawing late one night in Howard’s darkened apartment. It was rather spooky, sawing in the stillness, where others might wonder about the sounds coming from the home of their recently deceased neighbor. Howard’s presence in the room was surreal. It was so dark, so empty, and so quiet, except for the rhythmic chshsh-sh-chshsh-sh-chshsh-sh of the saw. During breaks, I would gaze at the nocturnal view that he had enjoyed for 17 years—the long avenues with their streetlights, the headlights streaming north and south along Lake Shore Drive, the dark vastness of the lake. I cannot remember how I transported those heavy shelves to my apartment, but once there, I loaded them with Howard’s beautiful books.

Howard’s albums in storage were of classical music and Broadway musical theatre, the books devoted mostly to bodybuilding and cooking. He’d also collected cookware of obviously high quality, made in Denmark, I think. The pots were white on the inside and bright yellow on the outside, with handles made of wood and bottoms of steel. Finding room for the cookware in my kitchen cabinets didn’t present a problem, as the cabinets had contained, to that point, a solitary plastic bowl to hold each morning’s helping of cold cereal. (“I do have a bowl,” I had once told my mother, upon her query whether I was even minimally equipped to dine in my own apartment.) I gave away Howard’s albums and his bodybuilding books. Though I later regretted giving up the albums, my severely crowded apartment seemed to require that I ruthlessly discard at least some of Howard’s belongings.

Last came Howard’s bed, which I decided that I liked. The mattress was essentially a futon and was covered by a white comforter with light-green stripes. Beneath the mattress, I found a few pages of gay erotica, and again thought of lines from “Soon”: “Love was the strange first cause / That bred grief in its seed.” I transported Howard’s bed to my apartment, where I set it on the floor next to my futon, which I soon gave away. I took the comforter to the cleaners. After it came back, I found myself sleeping in Howard’s bed, warmed by his comforter, with his pots in my cupboards, and surrounded by his books.

* * *

Illustration by Caroline Tomlinson

|

|

That February, I received a letter with a Florida return address from Mildred and Bernard Berkowitz, Howard’s parents. The stylish young woman whom I’d met in the lobby—and who turned out to be the lawyer handling Howard’s estate—had given them my name and address. “It must have been fate or a spiritual force that brought you and [the lawyer] together at that precise moment,” they wrote. “Howard loved books all his life. They were an essential part of his life. . . . From what [the lawyer] told us, you, too, love books, and your desire is to have a library. It is very comforting to us to know that these books are with someone who appreciates having them. . . . We hope that they will give you the pleasure and knowledge that they gave Howard.”

My stay at McClurg Court lasted about a year, including about nine months with Howard’s books. The books were a comfort and a joy to me during those dark days, when, inevitably, I had to confront the failure of the previous year and figure out what to do next. The immediate question was whether to return to law school, and if so, when. Northwestern generously had allowed me the opportunity to restart in the fall of 1993.

With his books lining my walls, I thought often about Howard during those months. I would stand at my own bank of windows and watch the clouds roll in from Lake Michigan, shrouding the gleaming white Water Tower Place and the black John Hancock building, the two towers juxtaposed like figures on a chessboard. I wondered about the thoughts that must have run through Howard’s mind over the course of the years when he had lived on the opposite side of the building. I pictured him and a companion seated at a table against his bank of windows, enjoying a meal that Howard had prepared; I pictured him in his reading chair, looking up from one of his beloved books to consider an idea and, once again, to admire his panorama of the city and the lake; I pictured him alone, standing at those windows, contemplating the beauty of the scene as a backdrop to timeless human mysteries. In particular, I wondered about the thoughts that had run through his mind as he stood at those windows for the first time after learning that he had been infected with that certain virus, and during the ensuing months of facing his onrushing demise, one that would cut his expected lifetime roughly in half.

Sometimes, seeking perspective on my own life, I would dip into one of the many biographies that Howard had provided and find reassurance from knowing that the lives of others—Simone Weil, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, and George Orwell, to name only a few—had been filled with their share of tumult.

In the late summer of 1993, I decided to wait yet another year and return to Northwestern in the fall of 1994. With that decision made, I also decided that I would pass some time in Colorado. Of course, taking Howard’s library with me would have been impossible. Therefore, in October, I loaded Howard’s books into boxes, rented a U-Haul, and drove the boxes and bookshelves to my parents’ home in Detroit, where they found storage in the garage.

There they would stay for 14 years: through my stay in Vail from November 1993 through May 1995 (while in Vail, I postponed my return to law school by yet another year); through law school from August 1995 through May 1998; and through nine subsequent years of lawyering in Illinois, Texas, and Washington, D.C. Then in February 2007, my wife and I bought our first home, a large colonial in Maryland. Suddenly, we had room for the books, which my parents brought in several carloads during the next few months. During their visits, I would return from the office to find a new batch of classics lining our basement shelves. I later moved some of those books to the loft above our garage, where I have my writing table. Brought face-to-face with these books after so many years, I started thinking once again about a man whose death was, in one respect, a statistic, a death that occurred during a distinct era in American history when gay men in large numbers were killed by a disease that seemed to come out of nowhere. Howard, of course, had been more than merely a statistic; he had been an individual, which led me to wonder about the life signified by the raised seal on the pages of these books. Who actually lived it? Put another way, what was the life story of the man who had provided me with hundreds of books full of stories?

* * *

Using the return address on the letter from Howard’s mother those many years ago, I managed rather easily to find Howard’s family. I spoke first with his mother, who was now 87 and who, upon receiving my call circa 7:30 p.m. on a Sunday night, was too surprised to be able to say very much, but who put me in touch with her other son, Robert. From Robert, I learned that Howard once had been married and that he had had a daughter. From talking with Robert and with Howard’s ex-wife, Kathy, and with his daughter, Rachel, I was able to find out more about the man whose wonderful library had ended up in my hands.

Howard was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, on March 3, 1944. Through most of his first 18 months, his father, an American soldier, was in Europe fighting in World War II. (Howard’s father was awarded the Silver Star for “gallantry in action” in southern France in August 1944.) When Howard was nearly four, his younger brother, Robert, was born. In 1949, the family moved to West Orange, New Jersey, where the two boys shared a bedroom.

Robert recalls that he and Howard were opposites growing up—Robert was the athlete, while Howard was given to a life of the mind. On the shelves that lined their room, Robert displayed trophies on his side, while on the other side Howard stacked the books on which he spent almost all his money. “Howard was always precocious, artsy, and creative,” Robert said. “Even as a kid, he took over the bedroom with his books.”

Howard went to high school in West Orange, then attended Rutgers University, still living at home. One day, while Robert was still in high school, he returned to find that Howard had removed the trophies from their room and put them in a box in the attic. In their place, he had left Robert a letter stating, “It’s time to get your act together, time to get serious!” Enclosed with the letter was a list of summer reading assignments, including a New Yorker article about the plight of India’s Untouchables, and books such as Crime and Punishment, Sister Carrie, The Grapes of Wrath. “Howard was eccentric, nerdy, an unusual young person,” Robert says. “He would call me a ‘suburbanite philistine,’ admonish me to get serious, and, like an idiot, I had to take him seriously. But he definitely had an effect on me. On the bus to high-school baseball games, as other players were discussing [the usual subjects], I was reading Darkness at Noon—and I was the captain of the team!”

Howard graduated from Rutgers with a degree in history in 1966 and married two weeks later. “We were very much alike,” says his ex-wife, Kathy. “What attracted me to him initially was our shared interest in classical music, the arts. He was sensitive, not a macho kind of person. And we both were very much against the Vietnam War.” Kathy adds, “He was very handsome. He had a very beautiful physique.” Both Kathy and Robert remember Howard as being about five feet ten inches, with dark brown eyes and a dark complexion.

Howard and Kathy moved to Baltimore, where Howard did graduate work in history at Johns Hopkins University. Their daughter, Rachel, was born in 1971. “He was an incredible father, terrific, lovely,” Kathy says. “He adored her—he was such a sensitive man.” Howard dropped out of the Ph.D program and began teaching in the Baltimore public schools. Ultimately, Howard’s inner conflicts—especially those involving his sexuality—came to light, and the couple separated. As for the reason, “Howard did not want me to tell his parents,” Kathy says. “But he and I had been such a close couple, and I had to give them an explanation. Howard was very angry when I told his parents.”

Howard went to work for Blue Cross; around the time when Rachel was three years old, Kathy, in search of a good public school system, moved with Rachel to Columbia, Maryland. According to Robert, Blue Cross asked Howard to become its director of communications in the mid-1970s, a promotion that took him to the company’s headquarters in Chicago.

Of Howard’s life in Chicago, Robert says, “He loved the city, he loved his view; he never had a car in all his years there, and he loved that freedom.” Also during those years, “he kept his distance from the family,” says Robert, today a writer living in Connecticut. “It was as though he had decided upon a whole new life. Sometimes a year or two could go by without him making contact. I would call him once or twice a year, just to let him know that I was still around, still available. Sometimes he would call me back, sometimes he wouldn’t.”

Robert visited Howard occasionally in Chicago, as did Mildred and Bernard. They had been surprised to learn their older son was gay. “They had had no idea, and it was all alien to them,” Robert says. “But they never stopped loving Howard.”

According to Kathy, she communicated with her former husband only to discuss details of Rachel’s child support. During the 17 years that Howard lived in Chicago, he did not have any contact with his daughter.

In January 1992, Howard had his first bout of pneumonia. “At that point, I knew he had AIDS,” says Robert, who, based on earlier conversations, had already begun to suspect his brother was ill with the disease. “At first, he didn’t want anyone to know. He tried to fight it; he thought he was going to beat it. But at some point when I asked him, ‘Do you want Mom and Dad to know?’ he said, ‘Yes.’”

With his life winding down, Howard sought reconciliation with his family. “It was as though he was going through a flashback of his whole life,” Robert says. Robert, Mildred, and Bernard visited Howard in Chicago. In a telephone conversation with Kathy, “He told me that he still loved me,” she recalls. “I think that psychologically, he wasn’t sure where he fit; he was not sure where he was, what he was. It’s a tragic story, [his] not knowing who he was.”

Howard also told Kathy that he would like to talk with Rachel, who at the time was 20 and a senior at the University of Delaware, pulling down good grades and swimming on the school’s team. Now 37, she lives in Annapolis, Maryland, with her husband and two children. “My mother told me that Howard would like to talk with me, that he would like for me to call him,” Rachel recalls. “I was upset and angry. I had never had any relationship with him, and always referred to him as ‘Howard’ rather than as my father. When I asked about him, I learned only that he was living in Chicago and that he never had remarried.”

Rachel could not bring herself to call Howard, but on September 7, 1992, she sent him a four-page handwritten letter. “All my life I have wondered what you were like, what you were doing, who you were,” she wrote in part. “Now, in one day, I know exactly what you are doing. I’m very sorry to hear about your illness[;] I hope you’re not in too much pain. . . . I always wondered why you never kept in touch with me. For a while, I hoped to get birthday cards, but I gave up that idea after a few years.” She asked if he would have contacted her if he hadn’t been sick. “Eighteen years is a long time to decide whether or not you want to make contact. I also feel a little hurt that now when I’m getting in touch with you [and] getting to know you, you will be gone from my life again.” She asked him to write back and signed the letter, “Your daughter, Rachel.”

Howard quickly responded in a shaky script, thanking Rachel for her letter. “I’m very happy we’re in touch,” he wrote. He said he hoped they could meet in person. “I think we’ll both find we have quite a lot we’ll want to tell each other. For now, let me start by trying to answer the difficult question you asked: Would I now be in touch if I were not ill? In truth, I do not know. I’ve always thought that, at some point, we’d get reacquainted and enjoy a healthy and rewarding relationship. But I never really knew how to decide when the time was right. Still, please know I always loved you and took great pride in the kind, dignified, and purposeful way you led your life. When I left on my solitary path 18 years ago, I thought it best to leave well enough alone and let you and your mother recover from a difficult separation and divorce while each of you in your own ways got on with your lives. I thought I did not have the right to come and go as I saw fit. I did not know if I was welcome. When I got into trouble with my illness early this year, I made contact with your mother to advise her of the situation. The question of what to tell you came up at once. We both were confused.

“My instincts were not to say anything for now. I did not want all this on your mind as you started your very ambitious final semesters in college. But in the end your mother concluded—and I agreed—the right course was to share the facts with you and let you decide what—if anything—you might want to do. I rejoiced when your letter arrived!” He signed the letter, “Love, Howard.”

* * *

Photograph: Courtesy of the Berkowitz family

Berkowitz shares a swing with his daughter, Rachel, in the early 1970s. “He adored her,” recalled Berkowitz’s ex-wife, Kathy.

With the end closing in, Rachel’s grandmother Mildred advised her to go to see Howard. “I was always very close to my grandparents,” Rachel says. “And so I went. It was the hardest thing I had ever done in my life.” Kathy went along, too.

At the hospice, a few weeks before his death, Howard was wheeled out to see them. “He was really far gone, physically unrecognizable,” Rachel recalls. As a nurse had warned, the disease had also taken a toll on Howard’s mind. Rachel remembers him saying: “It’s so good to see you. I haven’t seen you in a couple years.” Rachel told him that wasn’t accurate, and he asked when he saw her last. When she was three, she said. “Oh, I would never do that,” Rachel recalls him responding.

“It was one of the most emotional things I’ve ever experienced,” Kathy says. “Everybody was crying. Howard was not lucid. He asked Rachel, ‘Haven’t I been a good father?’”

Kathy adds, “The really magnificent person in this story is Rachel. She handled herself so beautifully. She did not confront him, but allowed him to say goodbye, to die in peace.”

For all its agonies, Rachel does not regret making the trip. “In his apartment, I found a box that held not only pictures of me, but also barrettes that I had worn as a little girl,” she recalls. “I had thought that Howard hadn’t cared about me, but when I found those things, I realized that he really had cared.”

Robert visited a few days before the end. “I was the last to see him, but had to return to Connecticut,” he recalled for me in an e-mail. “When I last saw him he was in a peaceful but somewhat delirious state. He was, however, alert enough to remind me to remove the cash from his wallet. When I saw the wad of greenbacks in his worn black leather wallet, it made me realize how almost to the end he believed he would ‘beat the sucker.’ That’s what he often called AIDS. Why else would he harbor the cash other than in the hope that he just might go on a last-minute holiday shopping spree for a few more hardback books and then slip out to one of the nearby neighborhood bars and buy drinks for patrons in celebration of his life and defeat of the ‘sucker’?”

Robert continues, “The thought made me smile until I realized that in surrendering his little hoard of cash it was his way of saying that his book-buying days were behind and he was okay with moving on to other things. I hugged him goodbye knowing that it would be our last hug.” The call came on Christmas Eve. “I remember sitting on my living-room couch and listening to Pachelbel’s Canon all day Christmas. It was one of his favorite pieces of music.”

Howard was buried in West Palm Beach, Florida, near where his parents were living at the time of his death. Rachel happened to be in Florida with the University of Delaware swim team. She borrowed one of the team’s vans and drove to the ceremony. “When I heard the rabbi say that Howard had been a loving father, I just sat there fuming,” Rachel remembers. She says that therapy later on helped her sort things out.

“Howard really, really cared for Rachel,” says Robert, trying to explain the mystery of his brother’s long separation from the daughter he adored. “But then—boom, he cut himself off. Probably he didn’t even know why. Some things are beyond our grasp.”

In my loft, I contemplate some of the hundreds of books that I inherited from Howard, and a few catch my eye: Franz Kafka’s The Complete Stories; Freud’s The Complete Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis; C. G. Jung’s Psychological Reflections. As for my search for the man who brought these authors together, I can imagine them—and even Howard himself—saying, “Well, what did you expect?” Howard’s life was as full of holes and contradictions as that of any other man, and to deconstruct him even modestly would require a biography as long and involved as any that I found in the lobby of McClurg Court on that day in January 1993.

His posthumous relationship to me remains relatively simple, however. In our love of literature we were of the same mind, and through his lifelong procurement of books, he left a legacy that was a boon to me at my own life’s nadir. Today, during spare moments, when I sit at my writing table and try to draft literary rather than legal prose, the heft of Howard’s collection, and the timelessness of the art contained in each volume, both intimidate and inspire me. I picture Howard receiving the books in the mail at McClurg Court over 17 years, and I can imagine his pleasure upon the arrival of each. They bring me pleasure, too, and for at least some of what I’ll read, think, and feel during my own lifetime, I’ll have Howard to thank.

Photograph: Courtesy of the Berkowitz family