|

Radar magazine’s June/July cover features a sexy, pistol-packing Lindsay Lohan linked to a story about the increasingly violent skirmishes between celebrities and paparazzi. A photo sidebar showcases 15 famous people flipping the bird for the cameras. That’s typical for the flashy and irreverent magazine, which routinely chronicles the missteps of stars, politicians, and the rich and powerful. The editor and founder, Maer Roshan, arrives via New York magazine and Tina Brown’s late Talk, and of course Radar resides in the publishing epicenter, New York City.

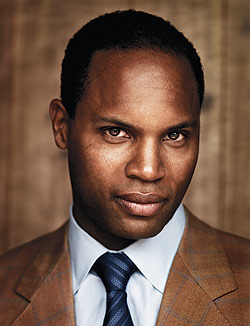

In short, despite a rather rocky launch-or, rather, several rocky launches-Radar has the DNA and mission to feed off today’s overheated, buzz-fueled, New York/Washington/Hollywood celebrity culture. With one anomaly: the magazine’s chief named backer is a media-shy Chicago businessman from a famous Chicago family-Yusef Jackson, the third son of the Reverend Jesse L. Jackson.

Why? “Radar was a great media property for the money,” Yusef Jackson says. “We were able to buy the assets at a good price, and I thought the previous owners pulled the plug too early. An independent product like Radar needs the time to prove itself-or not.”

The magazine had started up for two issues in 2003, stopped, rebounded for three issues in 2005, and folded. Last year, Jackson formed Integrity Multimedia Company, and the dormant Radar became the company’s first acquisition. Radar‘s new Web site débuted last September, and the first issue of the Jackson era came out in March.

Since Jackson stepped in, Radar‘s revival has generated the kind of gossip and conjecture that would make the pages of, well, Radar. Media reporters and pop culture columnists have speculated about the unseen hand of Ronald Burkle, the Los Angeles billionaire who made his money in grocery stores and private equity and who counts the Jacksons and Bill and Hillary Clinton among his good friends. Gawker, a New York–based media-and-celebrity blog that seems more than a little obsessed with Radar, claimed through an unnamed source that Burkle had put up about $8 million of Jackson’s initial $10-million investment.

Jackson, who is 36, won’t comment. “You’ll never hear from me what I’m investing,” he says, “and I never, ever, talk about my investors.” He adds with a laugh, “That’s what keeps my investors happy.”

Burkle, 54, did not respond to requests for an interview, but he has been both friend and financier to the youngest Jackson since the late 1990s. Jackson calls Burkle a mentor, a father figure, an adviser, and a friend. “I talk with him about my business life, my personal life, and I love to spend time with him,” Jackson says. “He’s as good a friend as I could ever have. He has given me the best advice in the world. He knows about my investment in Radar, and I talk with him about Radar sometimes.”

Jackson says that Radar attracted him because it offers a multimedia, multiplatform approach to publishing-a model in which a magazine is more than words and advertisements printed on shiny paper. In print, the magazine features long-form journalism in a distinctive voice; on the Internet, Radar‘s aggressive Web site breaks news and connects with viewers through videos and blogs; in the future, the magazine hopes to deliver content on cell phones and other devices.

“Radar is a work in progress,” Jackson says. “We’ve just published our second issue, and I think we’re still finding our editorial voice. It takes a little time.”

* * *

Yusef Jackson acknowledges that his interest in Radar may seem anomalous, but he says he likes the media business-it’s talking to reporters that bothers him, going back to his days as a freshman linebacker at the University of Virginia. “Given my family’s background-and we are a very public family and very public people-there has been a general interest in my story, and sometimes those stories have a tendency to drown out the products you’re offering,” Jackson says. “Often the stories are wrong and misleading, and I’ve even chosen not to correct them. I think the actual facts and the honesty and integrity of my intentions will over time outlast any particular story.”

A lawyer with a degree from the University of Virginia School of Law, Jackson in person is thoughtful, confident, and soft-spoken. When he talks about magazine publishing, he sounds anything but romantic, and he insists he brings to Radar the same attention to detail and bottom-line results that drive his principal business, River North Sales & Service, the profitable Anheuser-Busch distributorship he owns with his brother Jonathan. (The oldest Jackson son, Jesse Jr., is the congressman from the South Side and south suburbs’ 2nd district; he flirted with a run for mayor last year.)

River North Sales occupies space on two floors in a converted warehouse building west of the Loop, under the el tracks on Lake Street. Inside the front door, a flat-screen television mounted on the wall offers closed-circuit programming from Anheuser-Busch, with up-to-the-minute stock prices and slick features on the latest promotions for Budweiser distributors and retailers. The office, done in exposed brick and wood, is as businesslike and orderly as Jackson himself. His communications assistant, a young woman named Jennifer Donahoe, tells me the interview will begin “in six minutes,” and she fetches me in five. We walk up a flight of stairs to Jackson’s spacious office, which seems big enough to handle a Frisbee toss while you throw back a few Buds. We settle in on a couch and chair in the middle of the room, our conversation intermittently drowned out by the passing el train.

“If Radar didn’t learn from its first two iterations, then shame on Radar and shame on me,” says Jackson, who maintains that the magazine needs to broaden its editorial approach by appealing “to as many people in Kansas City as New York City.” He adds, “If I can develop a business infrastructure around smart circulation, not ego-based circulation -that is, focusing on bookstores and airports, versus spreading it to the mass markets too early-then we have an opportunity for success.”

Conventional wisdom in the media business holds that it takes gobs of money to sustain a consumer magazine until you can attract the right kind of readers-and enough of them-to make advertisers drool. Charles Whitaker, an authority on magazines and an assistant professor at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, points out, for example, that Condé Nast has spent between $100 million and $125 million to launch Portfolio, a business-meets-celebrity title that targets a readership similar to Radar‘s. “They’re betting they’re going to be hip and smart,” Whitaker says. “But they’re Condé Nast. They have very, very deep pockets.”

Jackson says that won’t be Radar‘s approach. “Conventional wisdom has large media companies, with portfolios of magazines, starting new ones and investing two years before they put out the first issue. This isn’t that. This is an independent magazine, and it can’t live by that model. We wouldn’t last a day under that model.”

Instead, Jackson says, Radar will attract an audience by breaking news on its Web site, generating buzz about its print articles, and seeking partners who can deliver its stories through cell phones, online television, and other means. The Wall Street Journal reported that AT&T had invested more than $10 million, perhaps with an eye toward using Radar‘s content to boost the company’s Internet presence. Kevin Belgrade, a spokesman for AT&T, confirms the investment, but not the amount-nor the company’s plans. “This is what our customers say they want, and we’re looking forward to seeing how Radar does,” he says.

Whitaker also points out that it helps to have a gifted editor with the vision to make the magazine stand out from its newsstand rivals. That’s Maer Roshan’s role. Radar is his baby (some would say his obsession). Roshan raised enough seed money from friends and family to publish two issues from his living room in 2003. The magazine emerged again in 2005 with the help of the real-estate and media mogul Mortimer Zuckerman, owner of the New York Daily News and U.S. News & World Report, and his partner, the financier Jeffrey Epstein. The two men pledged $25 million, but pulled the plug after three issues, claiming the advertising dollars weren’t there.

“I owe Mort a lot for taking a chance on this idea, but I am frankly mystified why he pulled out,” Roshan says. “Anyone who works at magazines can attest that three issues will not tell you what you need to know.”

Jackson and Roshan had met previously in New York, and Roshan says a friend of a friend brought them together. “I didn’t have a real great appetite for once again [recruiting] the people who had worked really hard for years without knowing there was someone who believed in the concept and would give it a real fighting chance. That’s what Yusef promised,” he says.

One source close to the magazine, who asked to remain anonymous to preserve relations with the principals, told Chicago that Jackson and Roshan have clashed over such issues as selecting vendors and making timely payments. Both men say it isn’t so. “Yusef has been true to his word,” Roshan says. “He has been supportive, with how much money we have to work with and how we’re going about [our business].”

Adds Jackson: “I control the budget and finances, and [Roshan] controls the editorial content. I think we’re doing fine.”

* * *

Radar’s circulation strategy begins online. With Jackson’s backing, Roshan relaunched the magazine’s Web site first, in September, and started breaking stories and making some noise. They included a piece on the CBS news anchor Katie Couric’s hairdresser, who pitched a fit when she had to fly coach on a Couric assignment to Jordan; Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly’s overblown claims that he was on Al Qaeda’s hit list; and Random House’s proposed settlement of fraud claims related to James Frey’s discredited memoir, A Million Little Pieces.

The site is averaging 755,000 unique visitors each month, and Jackson wants those numbers to double or triple. Still, Radar online got people talking, generating enough buzz for Roshan to put out his first relaunched print edition in March, followed by the June/July issue that hit the streets in May. A third issue is scheduled for September.

Roshan says the magazine aims for readers who like both celebrity gossip and in-depth journalism. “You have Us Weekly and you have The New Yorker,” he says. “But why can’t you appreciate JLo and be interested in the Iraq war? Why not merge those interests in one publication? It doesn’t mean they deserve equal treatment.” For example, Radar‘s June/July issue-the one with the cover story on the celebrity-paparazzi war-offers a strong investigative feature on how street gangs, including the Chicago-based Gangster Disciples, are infiltrating a U.S. Army desperate for new recruits.

Both in print and online, Roshan says he’s trying to combine the best of old media-serious, careful reporting, fact checking, and copy editing-with new media’s ability to deliver entertaining content in multiple ways. The multiplatform approach targets an audience the advertisers should love: urban, 25- to 39-year-old professional men and women, the so-called cultural influencers who have plenty of disposable income and are comfortable with blogs and online videos. The 120-page first issue had 31 pages of paid advertising, including ads for HBO, Showtime, Perrier, and tequila makers, and, not surprisingly, Budweiser Select. The second issue, at 112 pages, had 28 pages of ads.

“We knew that coming out of the history of the magazine, getting ad revenue would be very difficult, especially with a summer issue,” Jackson says. But he adds that the revenues for both issues were about the same, and he expects Radar to run more than 40 ad pages in September.

* * *

Despite the optimism, Radar faces long odds. “Everyone wants to figure out how to launch a smart, pop-culture magazine, figuring they can get young people back to print,” says Northwestern’s Whitaker. “But so far, no one’s been able to show how to get the kind of mass audience that one needs to make it work for advertisers. Radar keeps saying it’s something new and something different, but it really isn’t.

“Radar‘s got to generate some sort of engagement and buzz right away to make it,” Whitaker adds. “They’ve got to be the magazine version of YouTube, where young people feel they’ve got to be there. I don’t know that this idea is necessarily the one. But I’m pulling for them, and if it is, it’ll be great for the magazine industry.”

Jackson has vowed to fund the magazine for the next five years-a substantial undertaking, even if not on a Condé Nast level-which is probably why the media critics keep coming back to Ron Burkle, who placed 117th on the 2006 Forbes 400 list of the richest Americans, with a fortune estimated at $2.5 billion.

Burkle is a big investor in the Democratic Party-in March, he hosted a fundraising event at his home that helped to put $2.6 million into Hillary Clinton’s campaign war chest. And he has shown plenty of interest in media properties. In the past year, he joined with a fellow billionaire, Eli Broad, to make a run at Tribune Company (owner of Chicago), but was outbid and outmaneuvered by the maverick Chicago real-estate mogul Sam Zell. In May, Burkle’s Source Interlink, which distributes magazines, CDs, and videos to bookstore chains and grocery stores, announced it was buying Primedia’s Enthusiast Media, publishers of more than 70 special-interest magazines, including Hot Rod and Soap Opera Digest, for $1.2 billion in cash.

Burkle has known the Jacksons for years. In the late 1990s, Burkle’s private equity firm, Yucaipa Companies LLC, invested in a dot-com called OneNetNow, an early social networking site that sought to close the digital gap between whites and minorities. The firm attracted many black celebrities, including Sammy Sosa, then with the Chicago Cubs. Both Rev. Jackson and his son, Yusef, sat on the start-up’s board of directors, with Yusef serving as the board’s chairman.

Burkle and the Jacksons are no strangers to media scrutiny. There is, for example, the story of how Yusef Jackson came to own, at age 28, his lucrative Anheuser-Busch distributorship. By some accounts, the story begins with the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s launch of a boycott of Budweiser in the early 1980s, charging the St. Louis–based company with failing to award positions to blacks and other minorities. The company agreed to fund a minority distributorship program.

Some observers have linked Jesse Jackson’s actions to the subsequent success of his sons Yusef and Jonathan in winning an exclusive Budweiser distributorship from Anheuser-Busch. The story plays well in clout-obsessed Chicago-even though Yusef was 12 when his father launched the boycott, and 16 years passed before he actually bought the Budweiser business.

The details behind the Budweiser deal are far more complicated and help to explain the relationship between Yusef Jackson and Burkle. In 1996, Burkle asked the elder Jackson to come to a gathering at his home and give a talk about the need for more minorities in business. Yusef, then a young associate at the Chicago law firm of Mayer, Brown & Platt (now Mayer, Brown, Rowe & Maw LLP), went along. Yusef sat next to August Busch IV, son of Bud chief August III, and the two young men hit it off while talking about life with famous fathers, Jackson says.

Out of that meeting came the agreement, two years later, for Jackson and his brother Jonathan, a real-estate broker, to buy the Anheuser-Busch distributorship in Chicago. Jackson will not disclose the price but says he used “equity and bank debt” to finance the purchase. He also will not say how much River North earns. Annually, the business distributes more than three million cases of Budweiser and other malt beverages, teas, and waters to bars, restaurants, and sports venues in an exclusive swath of Chicago that runs from Irving Park to Roosevelt Road, and from Lake Michigan to Harlem Avenue.

Burkle has teamed up with Yusef Jackson several times since, including their $450-million play last year to buy the Washington Nationals baseball team (the team was sold to another group). In 2004 Jackson and Burkle were the high bidders, at $850 million, to buy the Chicago Sun-Times and its sister newspapers from the troubled Hollinger empire. Hollinger eventually decided against selling its Chicago properties, but Jackson says it only made him hungrier to join the media club. “It was a disappointing loss. I was interested in the Sun-Times because I thought it was a great city institutional paper, with a lot of history.” Jackson says that if the paper comes up for sale again, and the numbers are right, he will bid again.

By some expert accounts, a Jackson run on the Sun-Times would be as quixotic a media play as his backing of Radar. “Anyone interested in buying the Sun-Times would have to be very ignorant about the newspaper business,” says the veteran newspaper analyst John Morton. “No traditional publisher would be interested. It’s usually someone with a warm glow in the glands who buys a second newspaper, much to their everlasting regret.”

For the moment, the Sun-Times is not for sale, and Jackson seems focused on his new magazine. And whether it’s Burkle, or AT&T, or some other major investor he probably won’t talk about, he’s ready to consider all comers. “We’re small. We need lots of friends and lots of partners,” he says with a laugh. “It’s just like the beer business. Making friends is our business.”

Photograph: Kevin Banna