|

|

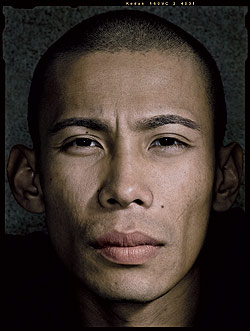

The menace is gone from the marine who talked. The strapped-on flak jacket, the gladiator helmet tugged low, the lizard-eye shades as dark and forbidding as limousine tints, the hostile, unsmiling face caught by a war photographer's lens. In its place appears the guarded, almost haunted demeanor of a man who has seen terrible things, done terrible things, who has examined them, worried them, and been scarred by them in the many ways war can wound. Hunched over a dining-room table in a modest home near Camp Pendleton, California, stripped of his gear and weaponry, Sgt. Sanick Dela Cruz appears reduced, self-conscious and alone.

Two and a half years ago, on a cool sunny morning in Haditha, Iraq, he was just another leatherneck, part of the time-honored hoo-rah fraternity. Then, on a routine resupply mission, a roadside bomb exploded beneath a vehicle in his convoy, killing one member of Dela Cruz's Kilo Company and injuring two others.

Dela Cruz escaped physical harm. But what happened on the morning of November 19, 2005, and what Dela Cruz would later say about it, would hurt him in every other way—even as it would help turn Haditha into a household name as notorious and controversial as Abu Ghraib.

Today, Dela Cruz's testimony underlies accusations that what occurred that morning—the killing of 24 Iraqi civilians, including babies, women, and elderly people, by a squad of marines—was a revenge-driven massacre. His words form the basis of a homicide charge against his squad leader and friend, Frank Wuterich, a man Dela Cruz continues to call "a great marine."

Dela Cruz, a graduate of Wells Community Academy High School in West Town who dreamed of dedicating his life to the Marine Corps, now finds himself in a painfully paradoxical position in relation to his military brotherhood.

Marines hew to a mantra almost as sacred as Semper fidelis: Leave no one behind. And with the men involved at Haditha, friends, families, and supporters have lived up to the creed in every way. Web sites such as DefendOurMarines.com and DefendOurTroops.com feature tributes to the marines of Haditha. Bloggers have said the troops acted "heroically" that day. Those supporters have scorned Dela Cruz, deriding his testimony that he watched Wuterich gun down a group of Iraqi men who were surrendering. "Dela Cruz is one of the sleaziest characters to emerge from the Haditha prosecution," declared one writer on FreeRepublic.com, a conservative blog site. As this article went to press, the supporters had reason to be pleased: Of all of the men accused in the killings, only Wuterich still faced charges.

Despite the "no marine left behind" creed, however, Dela Cruz has been largely forsaken. No Web sites solicit support for him. No ex-marines pen impassioned articles on his behalf. Dela Cruz says that even his family, once unflaggingly supportive of his military career, has questioned his decision to testify against Wuterich.

Dela Cruz's detractors dismiss the idea that they have left one of their own behind. If anything, they say, he abandoned the marines by turning on his sergeant. Dela Cruz himself insists that he is simply doing what a good marine must do: tell the truth.

Sitting across from me at a dining-room table in San Diego (the home belongs to a relative of one of his attorneys), Dela Cruz looks as small as his five-foot six-inch, 130-pound frame would suggest. The olive skin of his native country—the Philippines—has been burnished bronze by hours in the Southern California sun. He makes eye contact when he speaks, but his delivery is often halting and his grammar awkward from a lifelong struggle with English as a second language. He relies on "sir" as a kind of all-purpose punctuation and pauseword, the way other young men might use "like" or "you know." Only the tattoo crawling up his arm—a leering Grim Reaper clutching a sickle—hints at the bravado of the hardened fighting man he once was.

"I really don't like talking about this," he says, fidgeting, rubbing nicotine fingers together absently, as if trying to erase a deep scar: Indeed, while other Haditha marines have made their case to the media—Wuterich, most notably, having appeared on 60 Minutes—Dela Cruz has held his tongue until now, even after being granted testimonial immunity and having the homicide charge against him dropped. He agreed to speak to Chicago on condition that the story not be accompanied by photos showing the bodies of civilians killed that day, though they are easily found on the Internet.

"To be honest, I can't wait to get this thing over with and go on with my life," he says, "to just move on. But I can't do that until it's over." And for him, that means talking—and telling what he insists really happened.

* * *

The day began like so many others in Haditha, cool and clear, and ripe with the possibility of either tedium or terror. If the men of Dela Cruz's Kilo Company platoon—part of the Third Battalion, First Marine "Thundering Third"—had to guess, they'd likely have bet on the former. The mission, after all, was to be routine.

Their base of operations was Firm Base Sparta, a camp in a school they had commandeered shortly after arriving in Haditha, a town of about 100,000 on the Euphrates River near the Syrian border. Once a popular vacation spot, the city now found itself a strategically crucial supply line stop for the Sunni insurgency and the spread of al Qaeda.

Places like Fallujah had already become killing zones. Now, the marines believed that Haditha was next. Their mission was to secure the city's dam and prevent insurgents from taking over the town.

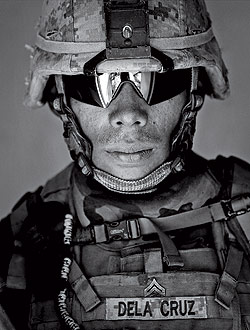

Rising at five that morning, they pulled on their body armor and stuffed ammunition into pouches—everything from grenades to cartridge magazines to night vision goggles they carried just in case. They slipped on sunglasses and strapped on camouflage helmets. Completely "kitted up," and looking like futuristic troops out of a Hollywood sci-fi flick, they prepared to move out.

At some point, Frank Wuterich conducted a briefing on the day's task. A four-Humvee convoy carrying a squad of 12 men would cross town to a southern checkpoint; drop off food, new communication codes, and a fresh squad of Iraqi troops; then immediately return to camp. Wuterich described the procedures they should follow in a number of scenarios, including what to do if the convoy was hit by the preferred weapon of the insurgent: an improvised explosive device, or IED.

In a moment of eerie prescience, one man joked about just that. "Somebody was saying, 'I feel like we might get hit,'" Dela Cruz recalls. "I told him, 'Man, don't say something like that!' It was, like, crazy."

The reality was, it would have been crazy not to be a little scared, particularly given the deadly stretch the Marine Corps had recently endured. Just that summer, six marine snipers from an Ohio-based company had been ambushed and killed not far from where the convoy was headed that morning. Shortly after, an IED had killed 14 more marines from the same platoon. Only a week before the morning of today's incident, three Kilo Company marines—friends of Dela Cruz—had been wounded by an IED on a similar resupply run.

At the dining-room table in San Diego, Dela Cruz shakes his head when he recalls the constant pressure. "I've seen my buddies get killed; I've seen the enemy get killed. You can't put your guard down because even though you might not see them, they always see you. You could be talking to someone and never know he's an insurgent. Every time you [left camp], you had to accept that I might be next."

If camaraderie helped the men cope, their training helped them survive. To the uninitiated, the harsh treatment and obsession with detail that marines suffer at the hands of the fabled drill instructor ('drill sergeant' is strictly an army term) can seem like senseless bullying. There is a payoff, however, beyond instilling basic discipline: It yields a mental toughness that can cut through the high emotions of a situation gone wrong. In addition, marines undergo extensive training in techniques to deal with an enemy who hides among the civilian population. At bases throughout the United States, the marines practice clearing houses, searching cars, and interrogating suspects. In Iraq they receive more counterinsurgency training, including classes in the rules of engagement—the guidelines that spell out when deadly force can be us

ed. Issued by the Department of Defense, the ROEs require that troops positively identify Iraqis as foes before engaging them. They also forbid marines to attack anyone who has surrendered or cannot fight due to wounds. At the same time, the rules stipulate that marines have a right to self-defense.

But, as Dela Cruz points out, the definitions of self-defense and surrender were moving targets. The ROEs were constantly changing. At times, for example, marines were allowed to fire if someone pointed a gun at them. Other times, they were required to refrain unless fired on.

The corps issued ROE cards, pocket-size summaries marines could carry into combat. The reality, of course, was that nobody whipped out a card in the middle of a tense situation. Not only was the notion absurd; it could get you killed. Most marines simply acquainted themselves with the basics, and when in doubt fell back on the golden rule, printed in bold block letters at the bottom of the card: "YOU ALWAYS HAVE THE RIGHT TO USE NECESSARY FORCE, INCLUDING DEADLY FORCE, TO PROTECT YOURSELF AND OTHERS."

Beyond those bare-bones instructions, the marines were on their own. They were not trained, for instance, in controlling their anger the way Chicago police officers in some jurisdictions are taught to keep their cool after high-adrenaline car chases.

Dela Cruz understood the regs and why they provided some wiggle room in a country where distinguishing friend from foe could be tricky at best. But about a week before the November 19th attack, Dela Cruz claims he had a disturbing conversation with Wuterich. Dela Cruz says that he and the squad leader were on a balcony overlooking Haditha Dam, smoking and talking about the IED attack a week earlier that had injured three marines. According to Dela Cruz, Wuterich mused, "If we ever get hit again, we should kill everybody in that vicinity . . . to teach them a lesson." Wuterich has vehemently denied that this conversation ever took place, says his lawyer, Neal Puckett.

In my interviews, Dela Cruz told me, "I would remember what he said for the rest of my life. I told him, 'Hey, you know who would do that kind of stuff? Saddam Hussein.'"

* * *

The convoy dropped the men and food off without incident, then turned back toward Sparta. The four Humvees—with Dela Cruz at the wheel of the second vehicle—lumbered through the just-stirring neighborhoods, grinding down Chestnut Road. Just after 7 a.m., the trucks crossed Viper Road, and a flash, followed by an ear-shattering KA-BOOM, shook the neighborhood.

* * *

|

|

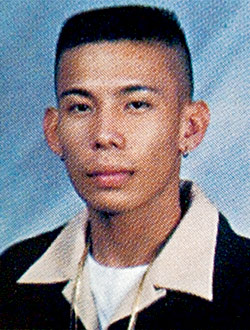

Sanick Dela Cruz seems an unlikely marine to be labeled a Judas. "He was an outstanding individual," says M.Sgt. James Miller, an ROTC instructor at Wells Community Academy High School. "He wasn't just a good student—he was a great student. He was a go-getter, a fixer of problems. He was a class leader." Miller adds something else: "He told the truth."

Ted Dallas, another of Dela Cruz's teachers at Wells, was equally won over. As the head of a (now defunct) urban horticulture program, Dallas admits he pushed his students, but Dela Cruz rose to the challenge, becoming Dallas's handpicked supervisor. "I'd love to have 28 kids like Sanick every year," says Dallas, who is now vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union.

The eager young student had a rough start. Born in 1982 in Cavite City, Philippines, a poor town a few miles southwest of Manila, he was abandoned by his mother and father to the care of his aunt. When the aunt moved to Chicago in 1997, Dela Cruz followed.

Living in an upstairs room in his aunt's Humboldt Park home, the teenager grappled with a new language (he spoke a Filipino language called Tagalog), a new culture, and a gang-torn Chicago neighborhood. "I was getting into trouble, hanging around with the wrong people, sometimes not coming home," he recalls. Several times his aunt kicked him out. The two went at it, he says, until she delivered an ultimatum: Follow the rules or leave for good.

The tough love worked. Dela Cruz stopped cutting classes and started turning in his homework. His grades rose. He made curfew. His newfound success seemed tenuous, however, until he found ROTC at Wells Academy—an 800-student school with a largely low-income student population that is nearly 75 percent Hispanic—and a mentor who clearly cared about him. "You could see he needed that father-type figure, a role model, to kind of vent and also to listen to," Miller says. "We'd sit down and talk and try to make some sense of what he was doing, and what his outlook on life was. All of a sudden he just took off."

By his junior year, Dela Cruz was pestering marine recruiters. "Sergeant Miller wanted me to join the army," he says. "He was trying to give me a hard time. He'd joke and say, 'Don't join the marines—they're crazy!' I told him, 'That's why I like them!'" Still, the recruiter who eventually signed him up didn't know quite what to make of the earnest young man who couldn't wait. "He said, 'You're the first one who actually approached me and said, I want to join,'" Dela Cruz recalls.

On the surface, Dela Cruz's enthusiasm echoes recruit poster cliché. "I wanted to serve our country," he says. "I wanted to travel and see what's out there for me. I wanted a challenge." Beneath the platitudes was a sense of familial connection. "From what I know, that's how my family came to the United States—because my great-grandfather joined the navy in World War II," Dela Cruz says. "My aunt said that because of my great-grandfather's service, she was allowed to become a U.S. citizen."

Dela Cruz earned his high-school diploma in 2002 and left for basic training that summer. Reality dawned quickly. After the first week of basic, he recalls, "I was like, 'Man, I don't think this is for me!'" he recalls. "But then I said I wanted to be a marine, so I kept going." That summer, in white cap and dress blues, he became an official leatherneck.

Around Christmas, he received his orders. "My roommate told me we're going to Iraq," he recalls. "I was like, 'You're kidding me. No way!'" In early 2003, Dela Cruz shipped out on the U.S.S. Boxer, bound for the Persian Gulf. In late February, a helicopter dropped him off in Kuwait and he was shuttled to the frontlines in Iraq. His exploits during his second deployment in a firefight in Najaf in September 2004 earned an admiring mention in a Marine Corps News profile. "Their names won't be remembered for their actions that day, except for a lifetime by the men who fought alongside them," the story intoned. "Men like Sanick P. Dela Cruz, a 21-year-old team leader from Chicago."

* * *

The man against whom Dela Cruz soon will likely testify, Frank Wuterich, came to the marines via a far different path. Raised in Meriden, Connecticut, Wuterich graduated in 1998 from Orville H. Platt High School, where he was an honor student, drama club president, and a jazz trumpet player. Like Dela Cruz, he enlisted in the marines during his senior year, but he did so in hopes of joining the Marine Corps band. Rejected, he found himself an infantryman, and a sergeant and squad leader in Haditha. The Iraqi village was his first combat tour of duty. Unlike Dela Cruz, he had never been in a firefight. He had, in fact, never been under fire.

Twenty-six at the time of the IED attack, Wuterich was about as far from the stereotypical vein-jutting "sarge" as his hometown was from Haditha. He was thin and baby faced, with sad doe eyes and dark hair. But he was a regular guy, appreciated for his laid-back demeanor. At home, Wuterich had a wife and three daughters, a responsibility that lent him an aura of maturity and made him a natural leader in a company of 19- and 20-year-olds. Among his men, Dela Cruz says, the sergeant's lack of combat experience was more a source of humor than serious concern.

When I asked Dela Cruz to name his best friend in Kilo Company, he looked up at me and said, simply and earnestly, "Sergeant Wuterich."

Not only did Dela Cruz like Wuterich as a person. He thinks that Wuterich probably saved his life. Not long before the November 19th incident, Dela Cruz was on patrol when he saw an elderly Iraqi man acting oddly. Wuterich noticed, too, and signaled to Dela Cruz to stop. "Next thing you know we found an IED right there," Dela Cruz says.

* * *

Photography: Marshall Photographer, Inc./Courtesy of Wells Community Academy High School

|

|

The explosion that hit the Kilo Company convoy shook Dela Cruz's Humvee. A plume of black smoke rose and a snowfall of ashy debris followed. Stunned, Dela Cruz called on his training: First, yank his Humvee to the side of the road in a herringbone maneuver (slant-park the vehicle to the right or left). Then dismount and prepare to engage. He grabbed his weapon, an M16 assault rifle mounted with an M203 grenade launcher. He shoved out the door and glanced around, looking for a possible triggerman. A white car was parked 20 meters away on the opposite side of the road. Next to the vehicle stood a group of five young men. Under the best of circumstances, a car filled with military-aged males stopped near a convoy would be regarded warily. Its proximity to the blast increased suspicion. "My immediate thought is, OK, maybe this was a car bomb," Wuterich told 60 Minutes in March 2007. "OK, maybe these guys had something to do with this."

From that point on, the accounts of what happened differ, devolving into a series of contradictory statements, alleged cover stories, and, some say, lies that to this day pit Dela Cruz and his one-time friend, Wuterich, against one another.

By Wuterich's account, Dela Cruz began shouting at the men in broken Arabic, yelling "Qif! Qif!" or "Stop! Stop!" The men ignored Dela Cruz and ran.

"Normally, the Iraqis know the drill when you're over there," Wuterich told 60 Minutes. "If something happens, they know exactly what they need to do. Get down, hands up, and completely cooperate. These individuals were doing none of that. They got out of the car, [and] as they were going around they started to take off, so I shot at them."

Wuterich stated in a hearing that Dela Cruz also fired. "Engaging was the only choice," said Wuterich, who had never been in combat before. "The threat had to be neutralized."

Asked by 60 Minutes how shooting a group of fleeing men could be considered justified, Wuterich said, "Because [it was] hostile action. If they were the triggermen, would have blown up the IED. Which would also constitute hostile intent. But also at the same time there were military-aged males that were inside that car. The only vehicle, the only one that was out, that was Iraqi, was them. . . . Those are the things that went through my mind before I pulled the trigger."

In Dela Cruz's version of events, the men at the car posed no threat. They were not running, and they were cooperating. In fact, they were trying to surrender. Some were standing with their hands up, others with hands interlocked behind their heads. Dela Cruz says Wuterich fired anyway.

Dela Cruz says he was puzzled at first, but then assumed his leader knew something, so he approached and performed a "dead check"—marine slang for making sure the enemy is dead—blasting the bodies with a short burst from his rifle. (Dela Cruz acknowledges that the rules of engagement actually required him to check on the condition of the enemy and treat them if necessary, not shoot them.) He says Wuterich then approached them and pumped shots into the men at point blank range. A forensic report would later show the presence of "stippling" on the men's corpses, indicating that some of the shots had been fired from a range of two feet or less. Puckett says that the marks resulted from the shots Dela Cruz fired into the bodies. Puckett denies that Wuterich shot the Iraqi men after they were dead.

Dela Cruz insists that the killings troubled him, but that there was little time to dwell on them. A Humvee had been hit. Marines needed attention. Approaching the blast site, he saw the company medic tending to a marine—Lance Cpl. James Crossan—whose legs were pinned under the vehicle's damaged bulk. Another marine, Lance Cpl. Salvador Guzman, limped around in a daze. "Get down!" Dela Cruz yelled. "Find cover!"

The Humvee had been torn in half. It slanted nose down in a large black crater, a plume of smoke hovering over it. Dela Cruz saw debris and blood, and then, he recalls, "I saw TJ"—Lance Cpl. Miguel Terrazas. "He was missing limbs, missing everything, his jaw. His expression, his face, his eyes were wide open. It was like he didn't know what happened, like he didn't know what hit him."

Dela Cruz says the sight devastated him. "My heart melted. I was like, Oh, the world is over." Terrazas, from El Paso, Texas, had been a friend, and one of the best-liked marines in Kilo Company. Around Sparta, he was known as the company cutup, regaling the other marines with tales of his trips to Tijuana, Mexico, jaunts that earned him his nickname of "TJ."

Now he was dead. Again, there was no time to dwell. Leaving the medic to tend the wounded, Dela Cruz grabbed a marine, Lance Cpl. Trent Graviss, and an Iraqi soldier, and led them north to begin searching houses. Wuterich, meanwhile, led a small squad toward a group of houses to the south.

With Graviss and the Iraqi soldier in tow, Dela Cruz kicked in the door of the first house. The three rushed in, weapons up as they went room to room. Nothing. They burst through the door of a second house, and a third. Nothing.

In the fourth house they found one elderly man and three younger men. They cuffed them, leaving the Iraqi soldier to guard them while they completed their sweep. As they worked, reinforcements arrived to evacuate the dead and wounded. Morning became afternoon.

At some point, Kilo Company's platoon commander, Lt. William T. Kallop, approached Dela Cruz's team and began talking in a rambling manner, Dela Cruz testified. "He was spazzing out over all the civilians that had been killed" in the homes cleared by Wuterich and his team, Dela Cruz recalls. "I was like, What the hell? What happened down there?"

Late that afternoon, a Humvee driven by Wuterich approached. The squad leader collected Dela Cruz and Graviss and took them to the houses Wuterich and his team had cleared. Wuterich ordered the men to remove bodies from the houses.

Before they got started, however, Dela Cruz says his squad leader pulled him aside. "He told me that if anybody asks about those guys—the five Iraqi males at the white car—that they were running away and the Iraqi army shot them," says Dela Cruz. At first, Dela Cruz recalls, he was confused. "Why would we have to lie if we didn't do anything wrong?" he says. Wuterich's attorney denies that the conversation ever occurred.

Still, as dusk settled over Haditha, Dela Cruz gave expression to the anger he had held inside him all day by doing something he later would deeply regret. He walked over to the bodies by the car and urinated on the head of one.

Dela Cruz turned to the homes and prepared to remove the bodies. In the waning light, he pushed open a door and peered in. "The first body I saw was an old lady," Dela Cruz recalls. "Her mouth was wide open and her hands were up."

In statements to investigators in March 2006, he described the rest of what he observed. "I . . . walked into the living room and remember seeing an old man laying dead on the floor in front of the door. I saw a woman lying dead at the end of the couch in that room, and I saw several children lying next to her at the end of the couch. I remember this house being badly burnt inside. I remember smelling burnt flesh and death. I didn't ask anyone what happened in this house, and I didn't really want to know."

Upon walking into the second house, Dela Cruz continued, "I remember seeing some dead children at the foot of the bed, and a female teenager laying dead at the bottom of the bed. I remember I was in shock from seeing all the dead people in this house. . . . I was going to try to pull out the body bags, but I just didn't bother. I just wanted to get the hell out."

* * *

|

|

A few days later, Kilo Company celebrated Thanksgiving at Base Sparta. Video taken of the day shows the troops in a festive mood, the men playing cards and digging into plates of turkey with gravy and stuffing. By now, much of Kilo Company was aware that a press release had been issued about the IED attack. The release claimed that a roadside bomb had killed one marine and 15 civilians. No mention was made of women and children. But even if any of the marines were troubled by the statement's inaccuracy, none stepped forward. Still, by one account, the killings that day—particularly of the women and children—appeared to weigh heavily on the company. Major Gen. Eldon A. Bargewell, who conducted an investigation months after the incident had occurred, wrote in a report, "At least one meeting was held in which company personnel were assured that, although civilians were killed, the marines had done the right thing and accomplished the mission."

Other evidence gathered months after the fact indicated that Kilo Company members harbored doubts about how "right" their actions had been. Several told Bargewell that they expected an investigation. At least one company photographer took pictures of the five Iraqis killed near the car "because he thought that the account he had received of their deaths was inconsistent with what he observed at the scene." A second photographer also took pictures because "he also expressed suspicion of their killings," according to the Bargewell report. In December, even before any investigations were launched, the company made a $38,000 condolence payment to a lawyer representing the families. "Condolence payments do not constitute an admission of wrongdoing," Bargewell wrote. "Nevertheless, [the payments] involved an amount unusually high."

Dela Cruz says the incident troubled him from the start. "It was like I was replaying it all the time," he recalls. "It was going through my head all day. I thought we might have done something wrong after Sergeant Wuterich told me to lie about it." Dela Cruz had learned to his dismay that the men killed near the car had been unarmed students. He had fired into the bodies of innocents and defiled the corpse of a civilian.

As months passed, however, the matter seemed to disappear into the sad, confused history of the war. But unbeknownst to Dela Cruz or the other marines, a young Iraqi man with connections to an Iraqi human rights organization purportedly had videotaped the aftermath of the killings. His footage showed the bloody, bullet-riddled bodies of children and women, some of whom were in their pajamas, and elderly men heaped in piles inside the homes. Survivors spoke on camera. One girl, who appears to be about 11, said, "We opened the door. My father was dead. We sat there. An American came in and shot at us. I pretended to be dead." An older man, about 55, said, "They opened the door and threw in a grenade. Then they went in and there were women and children inside. And they eliminated the family, and these children were only two or three years old."

Eventually the video was shown to Tim McGirk, Time magazine's Baghdad correspondent at the time. At first, "I was very skeptical," McGirk told me when I reached him in Israel, where he has since been reassigned. "I didn't see anything in the tapes that proved to my mind that these people had been killed by the marines other than the fact that they were in U.S.-issued body bags." McGirk says, however, that after he reviewed the press release issued about the incident, he grew suspicious. "I thought that [the marines were] either misinformed or knew more than [they] were willing to tell me."

The more he looked into the matter, the more disturbed he became. McGirk says he didn't have any reason to doubt the veracity of the video, and several factors suggest it was true: "The fact that these people had bullet wounds and not wounds that you'd see from a roadside bomb, that most of the people were killed by gunshots to the head and to the chest . . . and the fact that a representative from the marines came around to the mayor and basically apologized for what had happened."

In January 2006, two months after the incident, McGirk questioned the marine press office, and eventually marine officials launched an investigation.

Under the headline "Collateral Damage or Civilian Massacre in Haditha?" McGirk's story was published on March 19th. Scant attention was paid initially. Then, on May 17th, U.S. Rep. John Murtha, an ex-marine and staunch opponent of the war, came forward. A high-ranking marine official had told the Pennsylvania Democrat that what happened in Haditha was "much worse than reported in Time magazine. Our troops overreacted because of the pressure on them, and they killed innocent civilians in cold blood." Puckett says that some of the facts on which the story was built were later proved inaccurate. McGirk stands by his story.

* * *

The case exploded in the media. President Bush weighed in, saying he was "troubled" by the allegations. Some likened the case to the My Lai massacre in Vietnam. Members of the Navy Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) descended on Base Sparta and began interviewing members of Kilo Company. Rumors that Time would publish another piece made the rounds.

Wuterich grew particularly concerned, Dela Cruz says. Three more times, the sergeant asked Dela Cruz to lie, Dela Cruz testified. Again, Puckett strongly denies the allegation.

Dela Cruz says he initially told the navy's criminal investigators that he and the Iraqi soldiers shot the men standing by the car. The investigators, however, ordered him to take a polygraph test. When he failed, Dela Cruz says, he decided to come clean. "I just got tired of lying," he says. "It wasn't right. And I just wanted to tell the truth."

Puckett contends that Dela Cruz was not truthful. The defense attorney cites a federal agent's forensic reconstruction showing that the men by the car had been shot by two people. Dela Cruz says his "dead check" shots account for the extra wounds. Puckett contends that Dela Cruz, not Wuterich, fired the fatal shots. "We're not saying Sergeant Dela Cruz was wrong to open fire," Puckett says. "Both [Dela Cruz and Wuterich] are innocent of unlawful behavior."

In December 2006, eight marines were charged in the deaths of 24 Haditha civilians—the biggest U.S. criminal case involving civilian deaths in the Iraq war. The defendants included Wuterich, Dela Cruz, and two other marines, Lance Cpls. Stephen Tatum and Justin Sharratt, both of whom participated in the house clearings with Wuterich. Four officers who were not present during the killings were charged with failure to properly report and/or investigate the deaths.

Wuterich faced the most serious charges—murdering the men by the car and seven other civilians and ordering the murders of six more inside one of the houses. Since then, one by one, most of the charges have been either dropped or reduced. In Sharratt's case, a military judge ruled that Sharratt had acted within the bounds of the rules of engagement. Charges were dropped against Dela Cruz, Tatum, and other marines in exchange for their testimony.

As of May only Wuterich faced court-martial in connection with the killings. Rather than being prosecuted for the original charge of unpremeditated murder, however, he is scheduled to stand trial for voluntary manslaughter, aggravated assault, reckless endangerment, dereliction of duty, and obstruction of justice. If convicted, Wuterich faces a maximum of 160 years in prison, though legal experts say he would likely receive far less time.

Two other officers, Lt. Col. Jeffrey R. Chessani and 1st Lt. Andrew A. Grayson, still await courts-martial on charges of obstruction of justice and impeding the investigation.

Supporters of the marines say that the outcome proves that the marines were the victims of a media witch-hunt spurred largely by Congressman Murtha. Other observers think the case points out the difficulties in prosecuting troops during a time of war. "You look back at My Lai [in 1968, a massacre of more than 300 unarmed civilians, including men, women, and children] and you realize the military doesn't have a great track record for harshly condemning what soldiers do in war," Time's McGirk says. (In My Lai, of the 26 men charged, only Lt. William Calley Jr. was convicted. He was sentenced to life at hard labor but wound up serving only three years under house arrest.)

Still others argue that it is unfair to suggest that because charges were dropped against some marines in exchange for their testimony—or because conflicting evidence made it difficult to win convictions—it meant nothing untoward had happened in Haditha.

The report issued by Bargewell includes, if nothing else, a number of disturbing findings, among them:

—The initial reporting of the event was "untimely, inaccurate and incomplete."

—Several officers showed an unwillingness to investigate the case "bordering on denial."

—Marines violated the rules of engagement when they "did not follow proper room clearing techniques in the houses."

—Potentially exculpatory photographs of the houses cleared by the Wuterich team were lost or destroyed, perhaps intentionally.

Bargewell's report also points out that Dela Cruz cleared houses and detained suspects without firing a single shot: "This action is in stark contrast to how Sergeant Wuterich and his team handled a similar situation."

* * *

|

|

On August 31, 2007, nearly two years after the Haditha killings, Sgt. Sanick Dela Cruz took the stand in the Article 32 hearing of his friend and former squad leader, Frank Wuterich. (The hearing is the military equivalent of a grand jury probe, except that defense attorneys are allowed to cross-examine witnesses.) In halting English, Dela Cruz testified that he watched Wuterich gun down men who were, to his eye, in attitudes of surrender. He described the carnage he saw in the houses searched by Wuterich and his team. And he described the regret he felt at having urinated on the corpse of another human being.

The marine officer who presided over the hearing, Lt. Col. Paul Ware, scorned Dela Cruz's testimony. "On the witness stand he is unclear, easily confused, and acquiesces to counsel's questioning," Ware wrote. "Simply stated, Sgt[.] Dela Cruz's demeanor and performance in the courtroom is poor." Ware also cited the fact that Dela Cruz had defiled one of the bodies and that Dela Cruz initially had made false statements to the navy's criminal investigators.

Based on those findings and other conflicting testimony, Ware recommended dismissal of murder charges against Wuterich and instead urged charges of negligent homicide in the deaths of five children and two women. Lt. Gen. James Mattis, the commanding general overseeing the case, accepted the recommendations and will try Wuterich on the reduced charges.

Dela Cruz's lawyers, who have otherwise declined to comment, acknowledge that their client appears uncomfortable on the stand, but they explain that it's because he does not enjoy testifying and sometimes still struggles with the language. They also explain that there was no "deal" for Dela Cruz's testimony against anyone and point out that his statements and testimony have been consistent since he decided to tell the truth while still in Iraq, before any charges were brought against him and long before he talked to any lawyer or even knew immunity could be a possibility. Moreover, they say, Dela Cruz's credibility is bolstered by his willingness to admit to actions that cast him in a negative light, including having previously lied to protect himself and other marines and having engaged in certain "unprofessional actions" on that day.

Dela Cruz himself shrugs when I ask him about the assertion by Ware that he is not credible. "I'm not the judge," he says. "I'm just following orders now, [doing] what the government wants me to do. And I just leave it to the judge. They either believe me or not. But I saw the truth. I saw it."

* * *

Wuterich's court-martial had been scheduled for March but was delayed pending the outcome of a motion on whether the court could hear outtakes of Wuterich's interview with 60 Minutes. As this story went to press a date had not been set.

Of the four men originally charged with murder, only Dela Cruz and Wuterich remain marines. Wuterich has been reassigned to a desk job. "He's showing up to work," Puckett says. But "his life is on hold." In many ways, so, too, is that of Dela Cruz. As this story went to press, Dela Cruz was awaiting what he hoped would be the last time he must testify—at Wuterich's court-martial. Meanwhile, he was serving out his final few months at Camp Pendleton, escorting marine detainees to and from hearings and pushing paper.

* * *

On a warm San Diego afternoon, Dela Cruz rubs his thumb and forefinger together when asked to reflect on all that has happened. Since agreeing to testify against Wuterich, he says, he has received a chilly reception from some, but not all, of his fellow marines. But he knows his reputation will forever be stained. And he knows that for as long as he remains with the marines whispers will follow. "They don't say it, but you can kind of sense it that they think you're a traitor," he says. "But they don't actually know the truth." He has not talked to any of the men charged in the case, and likely never will. "Things will never be the same," he says.

* * *

As our conversation winds up, I ask Dela Cruz about the bodies by the car. Why did he desecrate one of them?

Up to this point, Dela Cruz had answered all of my other questions matter-of-factly and without hesitation. But at this one, he winces a little, casts his head down as he recalls the moment that haunts him most. "It was that afternoon," he says. "It was getting dark. . . ." His voice trails off. "At that time, I wasn't really thinking right, sir. Somebody told us to go up there, up the road, to check for more IEDs; I know I should not have done something like that, but I did it. That's not an excuse. It wasn't appropriate to do, but I did it. That's what happened. You're mad; you're angry over what had happened."

Did anyone see him? "I don't think so," he says. So why tell? He pauses for a moment. "So I didn't have anything to hide; so it doesn't come back to me what had happened."

Whether anyone else knew, he says, didn't really matter. "I knew."

Photograph: Lucian Read, embedded with Kilo Company