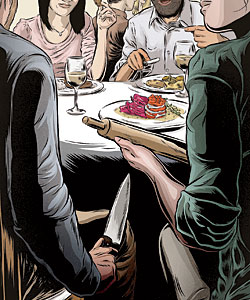

Last month, my wife suggested hosting a dinner party for the toughest crowd in Chicago. On the guest list: the Tribune’s dining critic, Phil Vettel; his counterpart at the Sun-Times, Michael Nagrant; Mike Sula of the Reader; and David Tamarkin and Julia Kramer from Time Out Chicago. As the chief dining critic at Chicago, I would presumably also be invited.

The idea sounded fun at first, a chance to exchange ideas and swap syrah-fueled tales with the few members of this entitled club into which we’ve all stumbled. Upon further consideration, the dinner began to assume an obscene, self-indulgent shape. But in the end, I nixed the party for another reason: These people are supposed to be my rivals. You don’t welcome your adversaries to break bread at the table where your children eat.

There is no honor among thieves, and thieves have a better rapport than writers. Most scribes circle their peers like dogs sniffing each other’s hinterlands: curious, ever careful not to reveal too much, nipping if anyone gets too close. History drips with scenes of writer-on-writer animosity, such as when John Irving said he could open any Tom Wolfe book and find a sentence that would make him gag or Norman Mailer coldcocked Gore Vidal at a party. The few people still interested in literary feuds now settle for following Twitter wars, which, when they’re between skilled writers, is like listening to Revolver on laptop speakers. I always imagine Tolstoy patting himself on the back after composing the perfect comeback for that twerp Turgenev, only to realize he went over the 140-character limit.

Related:

Inside the Mind of an Art Institute Guard »

Why the Professional Restaurant Critic Will Survive the Age of Yelp »

MORE BY JEFF RUBY

Finding the Perfect Bike in Chicago »

Barack Obama, Next-Door Neighbor »

Are Police Sketch Artists Becoming Obsolete? »

Facing His 40th Birthday, A Chicago Man Runs 40 Races »

Meet the Doughnut-Craziest Family in Chicago »

A Desperate Man Road-Tests Trunk Club »

Following a Freak Accident, a Father Faces a Grueling Choice »

One Hoarder’s Last Hope: Asking a Stranger to Move In »

Beer Tips From Steve Hamburg, Chicago’s Cask King »

Mutt Versus Jeff: One Animal-Ignorer’s Experience with the Wild New Family Dog »

Anonymous Restaurant Reviewing: Journalistic Gold Standard or Antiquated Parlor Game? »

Lousy Parenting: One Family’s Experience with Head Lice Removal »

This sniping is especially brutal in the food arena, by its nature a bitchy profession. In recent years, we’ve seen Mark Bittman (The New York Times) versus Alton Brown (Food Network) on the subject of TV food programming; Robert Sietsema (Village Voice) versus Josh Ozersky (Time) over ethics; and Anthony Bourdain versus everyone over anything. Foodies live for such battles and happily choose sides, while the rest of the world has no idea who these people are or why we care.

My favorite food writer of all time, GQ’s Alan Richman, has taken on Jonathan Gold of the Los Angeles Times over Chinese food in L.A., New Orleans over its post-Katrina restaurant scene, and various NBA Hall of Famers over nothing in particular. Richman is one of the sweetest guys I’ve ever met, but the man’s been in so many pissing matches over the years he’s got his urologist on speed dial. He fuels up with competition, and as his 15 James Beard awards attest, he gets pretty good mileage.

Me? My Little League baseball career ended when I was 12 because I no longer cared if my team won or lost—and often played like it. Now I find myself in a profession that rewards those with a killer instinct, the callous warriors whose hearts throb with bitterness for anyone else who happens to cover the same beat in a medium embroiled in a death fight for readers. “Critics hating other critics really is a grand tradition,” says Helen Rosner, senior editor at Saveur.com.

Sorry, Helen. I’m not built that way. I genuinely like Sula and Vettel and Nagrant and the rest—as journalists and as human beings. When they write something good, I send congratulatory e-mails; sometimes I even mean it. I recently saw Vettel at a wedding, and I did not feel compelled to punch him. We may have even clinked glasses.

So what’s wrong with me?

I asked Vettel, Tamarkin, Kramer, Sula, and Nagrant if we are rivals. Each answered unequivocally: no. No one, it seems, cares to ignite a shit storm with another writer, regardless of the attention it might draw. “I have struggled to muster much enthusiasm for these type of ‘rivalries,’ to the disappointment of my boss,” said Kramer. Even Nagrant, usually the prickliest of the bunch and a master antagonist when he’s so inclined, admitted that he never considered any of us competitors. “The whole scene was never a zero-sum game,” he said. “No matter how many people are competing for a similar story, there’s always another angle.”

Shocked, I asked Alan Richman whether a similar cordiality had arisen in Manhattan, where even the drinking water contains trace elements of spite. He assured me it had not. “Being miserable at work is part of the lifestyle [in New York],” he responded. “And so is resenting your rivals, who you’re sure have it better than you do.”

In Chicago, we have the same petty grudges, jealousy, and eye-rolling. But here’s where our scene swerves from the norm: Like good Midwesterners, we do our backbiting in private. A few years back, Tamarkin and I got in a minor kerfuffle over something or other—all I recall is that I was right and he was wrong—and I quietly expressed my dissatisfaction. He was mortified. The next day, by way of apology, I received a box of scones from Blue Sky Bakery. Mailer, it’s safe to say, would have force-fed Vidal the scones, and not into his mouth.

One could argue that we in Chicago save our aggression for the restaurants instead of one another, but as it turns out, much of the writerly angst has another source. In these uncertain times, neurotics like us are too focused on our own jobs—and whether we’re doing them well enough—to give the other guy much thought. “I already have a rival that I struggle with, criticize, and worry about,” says Tamarkin. “Myself.” In other words, if my wife had thrown that dinner party, the attendees would’ve been far too busy beating up on themselves to go after one another.

Illustration: John Phillips