The buzz doesn't get much better for a high-school basketball game. A half-hour before the opening tip, a Saturday afternoon capacity crowd pours into Loyola University's 5,500-seat Gentile Center. As many adults as teens cram into the stands. TV crews shuffle back and forth gathering footage of pregame warm-ups. Banners advertise corporate sponsors.

At the center of it all are teams from Loyola Academy and its North Shore rival New Trier. The Loyola Ramblers have spent most of the regular season ranked number two or number three in Illinois (depending on which newspaper was doing the ranking), and they are among the favorites in the state tournament that culminates March 17th in Peoria. Still, on this day, the main attraction is a certain Loyola Academy senior, a soft-spoken young man named Jeffrey Jordan.

Jeff is the firstborn son of Michael Jordan, arguably the best athlete the world has ever seen. For some in the crowd, this is history, like watching Babe Ruth's progeny play baseball. For others, it's pure curiosity: Is he any good? Other observers are coaches, scouts, and basketball geeks on a mission to evaluate Jordan's skills. A few years ago, he barely registered on their lists. Then, midway through the current season, talent scouts started calling the 18-year-old one of the better unsigned prospects in the country. Could things have changed that much?

Intensifying the spectacle is the presence of the Jordan family, who are surrounded, as usual, by bodyguards and university-hired security. National Basketball Association retiree Michael Jordan has folded his six-foot six-inch frame into a reserved seat directly across from the Loyola Academy bench. He occasionally shouts advice to Jeff and his younger son, Marcus, a talented sophomore also on the team. The boys' mother, Juanita, sits in a row above Michael. (A week after the game, the two announced they were filing for divorce.) Juanita is joined by Michael's mother, Deloris.

Celebrity sighting that it is, fans point at the Jordans throughout the game. Later, a few dozen people cluster around the family, prompting the security detail to close ranks. The initiated call this spectacle "The Circus," though that seems far too gentle a term to describe the attention and scrutiny that have followed Jeff Jordan on and off since grammar school. After a season filled with standing-room-only crowds, countless media interviews, and ongoing chatter about Michael Jordan's firstborn son, Loyola's Ramblers are poised for a strong finish. Though he's too reserved to admit it, much of what Jeff Jordan does in the next few weeks will determine how well Loyola Academy will fare-and which college he could play for this fall.

Win or lose, this basketball season is a milestone for this high-school senior, a very private young man's signal that he has survived and thrived under the weight of being heir Jordan.

Although the sporting world is filled with stories about children playing the same game as their famous parents, Jeff Jordan's career must surely rank as one of the more surreal. Few players have captivated audiences the way his father did during his 13 seasons with the Chicago Bulls (six championships, five MVP awards, and 14 all-star appearances, not to mention cultural phenomena like Air Jordans, baggy shorts, the movie Space Jam, and the heyday of the NBA). Simply put, Michael Jordan easily ranks with sports legends like Babe Ruth, Cy Young, Muhammad Ali, Walter Payton, and Bobby Hull.

"If you look at all the kids who have grown up with famous athletes for fathers, I'd say Jeff's experience is probably the most intense of all," says Jarrett Payton, son of the late Chicago Bears running back, and a Tennessee Titans draft pick.

Brett Hull, son of Chicago Blackhawks icon Bobby Hull, describes his own childhood playing hockey in Canada as a "nightmare"-and that was 30 or so years ago, before athletes attracted as much attention as they do today. Says ESPN basketball analyst Jon Barry, an NBA vet and the son of Hall of Famer Rick Barry: "[Jeff] is the son of the single greatest player to play the game of basketball. How can you measure up to that?"

The young Jordan, who fell in love with basketball as a toddler, acknowledges "the pressure of the name." But by the time The Circus surrounded him, Jordan says, he was enjoying the game too much to stop playing. "It was always still fun," he says. "No matter how much I thought about other things, and how much pressure there was, it was always fun."

His father tried to make sure it stayed that way. "We let our children be kids," Michael Jordan says. "Basketball isn't something to be feared, no matter who I am. I knew it would put pressure on him, but that doesn't mean he shouldn't enjoy himself and do things he wants to do."

|

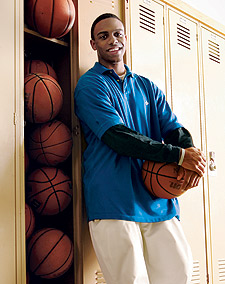

Jeff Jordan stands about six feet one with a thick upper body, the product of a rigorous weightlifting routine. These days he wears his hair short, a relatively noticeable change from the cornrows he wore until recently. His mother asked that he cut them before his high-school graduation this spring.

As his senior year winds down, Jordan busies himself with academics, college applications, and basketball. Several days a week, he wakes at 5:30 a.m. for a light workout inside the gym of the family estate in Highland Park. The goal is to complement the practice he'll have several hours later with the Ramblers, and some of the conditioning comes at the suggestion of his father. "My dad told me I should be getting in at least 500 shots a day," he says. Other days, he jogs while wearing a weight vest or runs through a series of defensive slides, a fundamental crouch-and-shuffle technique dreaded by even the most eager players.

Sometimes the Jordan brothers team up against their father on the court, but Michael Jordan says he avoids playing one-on-one. "I'm there to answer questions," he says. "We may sit down at the beginning of the season, and I may give them suggestions on what I feel they need to work on, but it's up to them to go and do it. I'm not standing over them."

After the morning workout, Jeff Jordan, early riser that he is, usually stops at a Starbucks and grabs a latté before school. During the day, he chews caffeine gum. He maintains a B-plus average at Loyola and already plans to major in psychology or business in college.

Exactly where that will be has not been determined. Jordan is cautious about discussing his plans, and the recruitment process will likely continue through the spring. Just to be safe, he sent in applications to Illinois, Michigan, and Georgetown-campuses where he would likely give up the sport and be just a normal freshman. But if he had it his way, he would play Division I college basketball. Until recently, there were doubts about whether he was good enough to play at the top-tier schools. In early 2006, smaller programs like Northern Iowa and Davidson were pursuing him, but that was before a series of spring and summer tournaments against the country's best prospects sent Jordan's stock soaring. Now he's waiting to see which schools come calling.

"He's going to have an outstanding college career," says Dave Telep, national recruiting director of Scout.com. Another college scout, Van Coleman, compares Jordan to a young B. J. Armstrong, the former unknown who played at the University of Iowa and, years later, helped the Chicago Bulls win three NBA championships.

Basketball and school keep Jordan occupied, but in his downtime, he's a typical high schooler. He loves sports video games and says his father has hooked him on old Westerns (Clint Eastwood gets the nod over John Wayne). With his dad, he pores over old episodes of Law and Order. "We could sit on the couch and watch Law and Order for days," the young Jordan says. Somewhat sheepishly, he admits to liking ABC's Grey's Anatomy, which he first watched with his mother. Like other teens, he's also into music. Jack Joyce, a friend since freshman year, says he and Jordan have been making up their own raps. Joyce describes his friend as humble and easygoing. "If you're hanging out at the same party, you would never be able to tell that he was Michael Jordan's son."

Jeff's attitude reflects how he and his siblings, Marcus, 16, and Jasmine, 14, were brought up. Both Michael and Juanita came from relatively humble beginnings. "We raised our children to be as down to earth as they could possibly be, given the circumstances," says Juanita Jordan. Though the family has lived in Highland Park since the children were little, the parents insisted that they spend time in and around Juanita's old Roseland neighborhood on the city's South Side. They hung out at Evergreen Plaza Mall and played in Fernwood Park. They traveled to Michael's hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina, too. "We wanted them to understand that the lifestyle that they have, and the amenities that come with it, weren't just given to them," their mother says. "You have to start somewhere."

Early one winter morning, Jeff Jordan, who is recovering from a bout with the flu, sits in the office of Loyola's guidance counselor and explains that his parents "were never afraid to tell me no." He earned his allowance based on how good his grades were, and it was all the spending money he'd see until the next batch of grades. "I know I asked for a lot of things when I was younger that they could have easily given me," he says. "But they were like, ‘No, you have to wait; you have to earn it.' So I think the values that my family instilled in me have definitely factored into how I look at things and how I want other people to know me."

Jordan also learned to be discreet-he declines to say how much spending money he actually got.

"We raised our children to be as down to earth as they could possibly be, given the circumstances," says Juanita Jordan. "We wanted them to understand that the lifestyle that they have, and the amenities that come with it, weren't just given to them."

Last year, Forbes ranked Michael Jordan the 26th richest celebrity in the world with a 2006 income of $32 million-and that's income drawn by a man who is, technically, retired. The Jordan name is a commercial brand worth millions, and the family is extremely guarded. Hovering over everything, one assumes, is the 1993 murder of Jeff's paternal grandfather, James Jordan, who was shot and robbed while sleeping in his car alongside a North Carolina highway. The accused, Daniel Green and Larry Demery, were sent to prison for life in 1996.

Today, security trails the Jordan family almost everywhere. Personal bodyguards monitor the children when they're on their own or traveling with their Deerfield-based Amateur Athletic Union team, the Rising Stars. Brian Davis, the boys' AAU coach, said he typically gives the security detail the team's game schedule and travel itinerary months in advance, just so they can make the necessary preparations. Davis says he even gives bodyguards notice if the team goes off schedule and, say, visits a McDonald's.

Security issues aside, the protective bubble also exists because almost anything a Jordan does makes the news. The on-court exploits of Jeff and his younger brother have grabbed the most attention of late, but so has their parents' plan to divorce, which made the front page of the Chicago Sun-Times in December. (As with most matters related to their personal life, they have refused to comment.) For his 18 years, Jordan has lived with ironclad rules and operated under the watch of a complex network of friends, family, teachers, coaches, and security staff. The boundaries between outsiders and insiders are distinct and difficult to penetrate.

My first meeting with Jeff, for example, took six weeks to arrange, and, at the request of his mother, interviews happened only on school grounds. In person, the young man is careful to filter himself. "[My parents] just told me, straight out, We don't want you to tell people this and we don't want you to say that," Jordan explains.

He says that, over time, he has established his own personal boundaries. To this day, there are certain subjects he'll hardly touch: anything comparing him to his father, for example, or any insinuation of a rivalry between him and his younger brother Marcus, or questions about "the North Carolina stuff"-references that link Jeff to his father's past. "I'm not him," the son always says. But he is also resigned to the fact that the questions may never stop.

Jeff Jordan was nine years old when the Bulls won the last of their six championships, so memories of his father's career come, he says, "in bits and pieces." He remembers driving with his father to games, visiting the locker room, and sitting on his mother's lap during championship rallies in Grant Park and informal get-togethers with other Bulls families. "I'd always have friends there, like Horace Grant Jr. [son of the former Bulls forward]," he says. "We'd just be hanging out." Much of that time involved basketball, Jordan says, and it was a sport he loved almost immediately. The Circus didn't exist back then. In fact, during basketball games at Bannockburn Elementary School, a carefree Jordan wore his father's number 23. He thought it was funny.

The Circus started after Jordan left the protective bubble of elementary school and stepped on an unfamiliar basketball court. "I asked my dad where the best middle-school players go, and he started throwing out some names of camps," he says. "Finally, he just started sending me to them."

In seventh grade, Jordan attended an AAU tournament in Virginia with the Rising Stars. Hundreds of fans, talent scouts, and sports reporters from across the country descended on a small court that, on any other day, would have drawn only a dozen or so parents. Michael Jordan sat in the front row directly across from the Rising Stars' bench.

During the game, the ball trickled out of bounds in the NBA star's general direction. Seizing the moment, one of the players on the opposing team dove toward the sidelines. The attempt wasn't to save the ball, but to make good on a chance to dive into the lap of a legend.

The stunt was innocent enough, and people laughed. But, to some, it signaled the end of Jeff's blissful anonymity. "You had to feel badly for the kid," recalls scout Dave Telep, who was there. "You had to wonder how it affected him." Telep and others assumed that Jeff would be traumatized and, say, switch to football in a matter of days. But Jeff says that well before that lap-diving episode, he had conditioned himself to block out the buzz that surrounds him. On that particular day, he didn't see the dive. "Honestly, I don't pay attention to anything around my dad unless I hear his voice," he says.

Strange as it may seem, the basketball court would become the one place where being Michael Jordan's son didn't bother Jeff. He continued to play in junior-high AAU tournaments around the country and progressed to invitation-only basketball camps, even a frighteningly symbolic showcase at the University of North Carolina, his father's alma mater.

"I've never tried to encourage him in either direction," Juanita Jordan says. "Michael and I have always supported what he wanted to do and primarily it's been basketball." Still, the camp at Chapel Hill sticks out as an especially difficult moment, she says. "I thought that might be a lot of pressure. I just thought that it would raise questions about his college career and all sorts of other comparisons. But it was a great experience for him."

Today, Jordan looks back on those years as a sort of honeymoon. The "pressure of the name" wouldn't reach its full force until he entered Loyola Academy.

As a freshman playing on the sophomore team, Jordan, now wearing number 32, entered his first varsity game with minutes to go in the fourth quarter. Loyola was losing badly, and fans were chanting "overrated" every time he touched the ball. "That was shocking because I didn't think people knew who I was," he recalls. At other games, fans wore his father's old jersey and screamed, "You're not him!" Some would go so far as to mimic the old Gatorade ads and sing, "If I could be like Mike. If I could be like Mike."

On the court, Jordan became a target for unusually hard fouls and players with something to prove. Every player wanted to score on a Jordan and, if he couldn't do that, at least to foul him hard. "He's never complained," says Joey Suhey, a Loyola Academy teammate. "He just pops right back up and walks to the free-throw line." (Suhey's father, Matt, was Walter Payton's longtime blocker; he played on the 1985 Chicago Bears Super Bowl team.)

The summer between his sophomore and junior years, the Nike All-American Camp in Indianapolis invited Jordan to an event where top college prospects show their skills to dozens of college coaches and scouts. During the week, the players attend media-training classes, which culminate with each player having his own news conference. Most athletes walk in to find no more than a handful of reporters, typically someone from their local paper or a recruiting Web site.

Jeff Jordan, on the other hand, walked into a conference room filled with several dozen reporters and, he recalls, "40 or 50" TV cameras. Later, he was ushered into a dimly lit suite so he could be interviewed by ESPN. "I was nervous," he recalls. "But whatever [they] asked me, I pretty much tried to keep my dad out of the answers because I didn't want that to be used against me in any way." A reporter from Japan even called his hotel room requesting an interview.

On almost every court, Jordan was judged more harshly than most. "The toughest thing for scouts was trying to understand who Jeff was, versus the player that everyone thought Michael Jordan's son should be," says Jerry Meyer, a scout with the recruiting site Rivals.com. "I certainly had to fight that."

"I think it could have hurt my recruiting more than it helped, just having the name," Jordan says. "The only thing I can do is work harder, and that's also what's going to fuel me in college. Just thinking about what could have happened if I didn't have my name."

Making matters even more difficult for the high schooler, other scouts say, was the fact that some college coaches were reluctant to recruit him. Apparently, they were intimidated by the very idea of dealing with "a Jordan"—and the father, family, and bubble that surround him.

Today, scouts say all of it conspired against Jordan so that he was "undervalued," an issue that the teen seems keenly aware of. "I think it could have hurt my recruiting more than it helped, just having the name," Jordan says. "It ticks me off sometimes, just because I know there's nothing I can really do about it. It's a coach's decision to either call you or not call you. The only thing I can do is work harder, and that's also what's going to fuel me in college. Just thinking about what could have happened if I didn't have my name. I think that's going to be a big factor in my improvement over the next four years."

The game at the Gentile Center ends with Loyola defeating New Trier 60 to 55, with 21 of Loyola's points coming from Jeff Jordan, who has led all scorers. Fans stream toward the exits, ignoring a second contest pitting number-one-ranked Simeon High School, one of the better teams in the country, against Carver Military Academy. Meanwhile, the 18-year-old submits to the inevitable postgame interviews.

Standing just a few steps from the court, the senior looks tired but characteristically composed. He leans toward a TV microphone and answers each question with a fairly succinct sound bite. There's a question about his two-handed dunk (his favorite move), then one about the pressure of playing in front of his father (Jordan is expecting Dad to give him a postgame "critique"), and something related to his team ("If we keep taking it game by game, we'll be all right"). Then comes a question that gets to the heart of the matter:

"Do you ever smile?" the TV reporter asks. "It wasn't until the last five seconds of the game that I saw you smile."

Jordan chuckles. For most of the game, his facial expression had ranged from furious to serious. The intensity of the action demanded it, of course, but Jordan is also a Jordan. He has to think twice before showing emotion. In public, at least, he has to think twice about almost everything.

"Yeah, yeah, I definitely smile," Jordan says with a grin. "I love playing in front of the fans and everything like that. So, at the end of the game, when I knew we had it wrapped up, I was happy." The interview ends, and the smile disappears. He shakes the reporter's hand, turns toward the exit, and walks to the locker room.