This is about as good as it gets these days for former Cicero town president Betty Loren Maltese. She's sitting in the visitors' room at the federal prison in Victorville, California, devouring chicken wings from the prison vending machine and washing them down with her second Diet Coke. It's nine o'clock in the morning. Normally at this time, she would be cleaning the front lobby and bathrooms at the men's prison next door, but today she's talking to a reporter who has brought lots of quarters for snacks.

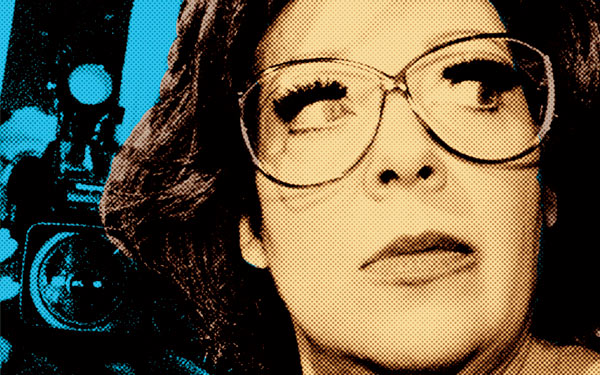

As she feasts on junk food, Betty, now 58, is barely recognizable. Dressed in dark green khakis, she looks more petite than voluptuous. She's replaced her Liz Taylor–style wig with a baseball cap. Her false eyelashes are gone, as are her trademark big glasses—she was mixing a giant bowl of oatmeal cookie dough in the prison kitchen and they fell in and broke. She wears a little bit of lip gloss bought at the prison commissary, but otherwise her face is bare. She's lost four teeth and says she feels like a Halloween pumpkin. She's not puffing on a cigarette. The prison doesn't allow smoking, so she was forced to give up her two-pack-a-day habit.

Betty chews on her wings and smiles as she tells a story about her ten-year engagement to her late husband, Frank Maltese, a convicted bookmaker for the Cicero mob boss, Ernest Rocco "Rocky" Infelise. She says she suspected that Frank had been cheating on her and decided to leave him. Shortly after the breakup, she says, she got summoned to meet with Infelise, who was known for his ruthlessness. "I was scared, but I went and he couldn't have been nicer," Betty recalls. "He said, ‘Frank loves you very much and he's very sorry.' Rocky told me Frank was heartbroken and wanted a second chance. Just a friend concerned about another friend."

Of course, some people in Cicero claim that Rocky also summoned Frank and—given what he feared might be Betty's knowledge of the Cicero mob—gave him a choice: Marry her or kill her. Betty laughs at the suggestion. "Well, I wish he had killed me," she says. "It would have saved me from all this."

Betty Loren Maltese has been in prison in California for five years and still has two more to serve for her role in an insurance scam that stole $12 million from Cicero. She calls the last year the worst of her life. Her family is in turmoil. Her benefactor, Chicago lawyer Ed Vrdolyak, who now faces criminal charges himself, has cut way back on the financial support he was giving her family. In December a judge rejected her latest appeal. She still insists she's innocent and has an aggressive new lawyer who specializes in getting wrongful convictions overturned, but at this point the odds for her are slim.

Betty has seen her 86-year-old mother, Kitty Loren, and her ten-year-old daughter, Ashleigh, only once in the past year. Ashleigh is living with Betty's estranged sister in a small town in Alabama. Last summer, the little girl learned through the Internet that she had been adopted and that her mother was in prison, not simply working away from home, as Betty had long told her. Citing an old newspaper story, Ashleigh told Betty, "You just used me as a pawn to stay out of jail."

Today Kitty Loren can barely see. She lives alone in Betty's Las Vegas house, which briefly went into foreclosure in the fall after Vrdolyak stopped paying the mortgage. "How could he do this to us now?" Betty asks of the lawyer who made millions doing legal work for Cicero and served as her political adviser. "Ed always wants me to be in need."

But she seems to like to keep him on edge, too. "Prison is hell and I don't think Ed could survive it," Betty says in reference to recent federal fraud charges against Vrdolyak for his alleged role in a kickback scheme. But she doubts he'll ever be convicted. "He's untouchable because of his connections," she says.

Connections to what? Betty won't answer. She says she can't because she worries about Ashleigh and her mother. But when she gets out, she might write a book. "I always have said the whole Cicero story will eventually come out. I just hope it's sooner rather than later. I have to get out of here."

Betty Loren Maltese does have a story to tell. A girl from Louisiana without an ounce of Italian blood drops out of high school, marries a charming operator with dangerous friends, and becomes the mayor of Cicero, the onetime stomping grounds of Al Capone. Throw in "Fast Eddie" Vrdolyak, the colorful ex–Chicago alderman and legendary power broker, and it's a juicy tale.

She and Vrdolyak met through Frank Maltese, who brought them both into Cicero politics. Betty says Frank and Ed were very close. They often had lunch together and took trips to Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe that did not include wives. When Frank became ill with pancreatic cancer, Betty says, she was touched by Vrdolyak's devotion in visiting every Sunday.

Vrdolyak was already doing legal work for the town when Betty became town president in 1993. At the time, she says, she didn't really know him well. After Frank died, they became friends, and she says Vrdolyak became her closest adviser as town president. When Betty adopted Ashleigh, she asked him to be her daughter's godfather. "He is a good father," she says. "He loves his son and grandkids so much."

Vrdolyak says he takes his role as Ashleigh's godfather seriously and has stayed close to Betty's family while she has been in prison. Although clearly exasperated at some of Betty's comments, he refuses to get into a public war of words with her. "She's under tremendous pressure," he says. "I have great sympathy for her. Being in prison is devastating, especially when you have a young daughter."

Some people close to Vrdolyak have questioned Betty's mental stability. She says she suffered from the anxiety disorder agoraphobia and took medication for panic attacks for years. At one point, she says, she was hooked on prescription drugs. "After Frank died [and I became town president], I knew I had to stop," she says. "I [still had] panic attacks, but not as bad since I knew what they were." (Her lawyers—even those with whom she's had a falling-out—say that though she can be demanding and unrealistic, she is not mentally impaired.)

Shortly before she reported to prison in early 2003, Vrdolyak told her to write down her expenses, and he promised to cover them. She says they totaled close to $100,000 a year, including the mortgage on her $460,000 Las Vegas home, Ashleigh's private school tuition, and big credit-card bills she had racked up gambling before she went to prison. She says he asked only that she keep it quiet.

Each month he sent Kitty Loren a check. Despite the generous help, after a year in prison Betty was getting upset. Her appeal was moving slowly. "Every day feels like a year," she said at the time. She talked to Ashleigh every night on the phone, but the fiction about being away at a job was becoming hard to maintain. "She says, ‘Mommy, please quit and come home,'" Betty said. "‘I need you.'"

Meantime, she says, Vrdolyak came to visit her in prison in California only once and stayed for less than half an hour. His checks were sometimes late. He continued to work in Cicero for Betty's successor, Ramiro Gonzalez. In 2003, records showed that Vrdolyak's law firm had billed the town close to a million dollars. "I think he is quite happy I'm here, as are some of his buddies," Betty has said. "I was too hard to control."

Reporters, prosecutors, and even some of her friends wondered how she kept up her family's expensive lifestyle with no source of income. Some speculated that the money came from the outfit or that she had stolen it from Cicero. Neither perception helped as she pursued her appeal.

So in February 2004, she outed Vrdolyak on Fox News. She allowed her family to give the TV station copies of his checks. In an interview, she played a cat-and-mouse game, linking him to the insurance scam by saying she consulted with him on everything she did as town president. "[Ed] knows I'm not guilty." She ended the interview by saying, "Some powerful people don't like me." Should they be worried? "They might start thinking about it," she answered with an eyebrow arched and a firm nod.

Publicly, Vrdolyak confirmed he was supporting the family. "I do think Betty is innocent," he said. Privately, he was disappointed. A short time later, the government subpoenaed his law firm's billing records.

Still, he continued sending the money. Why? A friend of his has said, "He cares about Ashleigh and is loyal to Frank. That's just the kind of guy he is—he's loyal."

"I won't walk away from a friend in trouble, no matter what they say or do," Vrdolyak says. "I know what that's like." As a young law student in the 1960s at the University of Chicago, Vrdolyak was accused of attempted murder. He was found not guilty, but he says a lot of people abandoned him at that time, and he has never forgotten it.

Now Vrdolyak faces fresh legal troubles. This past May, U.S. attorney Patrick Fitzgerald announced that Vrdolyak had been indicted in a kickback scheme involving the sale of a Gold Coast building, a deal he allegedly had worked out with Stuart Levine, a political insider who has already pleaded guilty in two separate public corruption cases. Vrdolyak has pleaded not guilty. Levine is awaiting sentencing while cooperating in the ongoing investigation, according to the U.S. attorney's office.

Today, Betty and Vrdolyak are no longer speaking. Days before the foreclosure on her house became official, he sent a check, which—along with help from friends—averted the action. She calls it "guilt money," but she is grateful he continues to help her mother.

Cicero legend holds that Betty Loren met Frank Maltese in 1970, while working as a cocktail waitress at a mobbed-up topless bar and brothel. "I never stepped foot in that place," she insists. "Even then, I didn't have a good figure. I would never even wear shorts. I can't even stand to see myself naked."

In fact, she says, she met Frank at a bingo game with her mother. When he heard she was getting a divorce, he started coming to a restaurant in Berwyn where she was working as a waitress. Frank kept asking her out, but she refused. "I was 22 at the time, and I thought he was too old," she says. "I didn't find him sexy, and I was kind of fed up with men." Frank was 19 years older, short and rotund, and nicknamed "Baldy." He had been married twice, and he had two children.

Finally she agreed to a date. In the beginning the courtship was G-rated, she says. Frank took her to Las Vegas with friends to see Frank Sinatra perform. Because of a booking snafu, the couple were forced to share a hotel room. "I was so nervous," Betty recalls. "I went to bed in my evening gown and full makeup. When I woke up the next morning, Frank was still sitting on the couch, staring at me."

Eventually they moved in together, living in a bungalow on Austin Boulevard. Betty got her GED and real-estate agent's license. She held a variety of jobs, including running a small newspaper and a deli. She says that Frank sold cheese for a pizza company. He had grown up in Cicero with Rocky Infelise and other outfit guys, but Betty says he had stayed friends with them while choosing a different life. "I'm friends with a lot of priests, but that doesn't make me a nun," she says. To this day she insists Frank was no mobster or bookie.

By the time they married in 1988, both were working for the Town of Cicero. Over the years Betty had a number of jobs at town hall. She ran the traffic violations department, worked for the liquor commissioner, and served as an aide to the town president. Though Frank served as the town assessor, federal prosecutors claimed that his most important job was to act as a link between the mob and town hall. He also ran a gambling ring for Infelise.

Frank was a popular figure in Cicero, outgoing and friendly. He wasn't violent, and he never became a "made man" in the outfit, according to Jim Wagner, president of the Chicago Crime Commission. But he had influence behind the scenes as a political operator for Infelise and his successor, Michael Spano. Betty still speaks highly of her late husband. "If he had five dollars, he would give you five dollars. He cheated on me and I wasn't in love with him. But he had a good heart."

In 1990 the feds charged Infelise and 19 of his crew, including Frank. A year later, Infelise was convicted of racketeering and sentenced to 63 years in prison. (He died in prison in 2005.) Already sick with cancer, Frank pleaded guilty, but died before going to prison. Before his death, prosecutors say he made two big moves. In July 1992, he and the then town president, Henry Klosak, arranged for the town's insurance business to be transferred to a company called Specialty Risk Consultants, controlled by Michael Spano, Cicero's new acting mob boss. Five months later, Klosak died suddenly. In January 1993, Frank helped persuade the town board to name Betty as Cicero's interim president. Betty says she was chosen because they thought she was the only Republican who could get elected in Cicero. But one of Spano's associates later testified that the mob boss thought Frank could control her. In the spring, she was elected outright. Frank died that fall.

From the start, Betty vowed to shake things up. She cleaned the town up physically. She appointed a youth commission to improve sports and play facilities, and she provided bus rides, outings, and snow clearance for seniors.

Although a source close to Vrdolyak says he complained of having a hard time getting in touch with Betty when she first took office, she says she consulted with him about everything. With a population around 80,000, Cicero was becoming increasingly Hispanic, but Betty and Vrdolyak were able to bring Hispanics into town government and keep Cicero under Republican control. With Vrdolyak's guidance, she built a strong political organization and had a huge political war chest. Her wisecracking, tough-gal persona, flashy clothes, and big hair played well in the bungalow belt and captivated the media.

Betty said she wanted Cicero to shed its reputation as a home to the mob. Nonetheless, she acknowledges she spent time with Spano, though she claims they didn't talk much about town business. He often took Betty and her mother for gambling excursions on the riverboats.

Around the mid-nineties, town employees started to complain about their insurance—high costs, bills not being paid. (Prosecutors say she fired Cicero officials who brought up the problem—something she denies.) She says that by the time she got her hands on the matter, she was already at odds with Spano. "I shut down the strip clubs, the 6 a.m. taverns, the poker machines," she says. "Everything I did was anti-mob."

She says Vrdolyak warned her there would be trouble and he was right. Neighbors say they saw Spano pull up in his car to Betty's house with some other town officials. "He told me it would be good for my health if I didn't run again. If I had had Ashleigh at the time, I would have done what he wanted, but I was angry. I had worked my ass off for the town and I wasn't going to let him push me out."

A slate of candidates led by a former town employee, Robert Balsitis, challenged her in the 1997 GOP primary, but she won that and the general election by a landslide. There was a price to pay. The two sides hurled accusations at each other, especially about the insurance problems, and the accusations attracted the attention of federal prosecutors. Even with a federal probe in full throttle, Betty was elected to a third term in April 2001. But two months later, she was indicted, along with Spano, former police chief Emil Schullo, former town treasurer Joseph DeChicio, and six others. They were charged with siphoning off $12 million in phony insurance claims and laundering the money into a Wisconsin golf course they hoped to turn into a casino resort.

During her trial, Betty's lawyer, Terry Gillespie, described her as someone who was in over her head. But that was hard for many to accept, including the jury. On August 23, 2002, after deliberating for 11 days, it found Betty guilty of racketeering conspiracy and fraud. "If you are so powerful and in control that you can run a town down to the street corners, how can you say you had no idea what was going on with the finances?" asked Tom Kilpatrick, who was the president of the Chicago Crime Commission at the time. "Betty wasn't the stereotypical mob wife who went to church and stayed out of the business. She was a powerful and shrewd person."

Still, some people who worked with her say Betty was unsophisticated about financial matters. "She relied on her auditing firm, and they didn't pick up on it," says Ed Setlick, an accountant who helped on the Cicero budget for ten years. "The insurance fraud was well disguised and not easy to see."

Shortly after he went to prison, Emil Schullo, one of her coconspirators, told me, "I think [Spano and the mob] probably saw her as—excuse the expression—a dumb broad." Schullo said Betty was easily manipulated and listened to the wrong people. And she was her own worst enemy. "She's the type that would throw you out of a moving car and then drive around the block and give you a crutch."

In 1997, while she knew she was under federal investigation, Betty arranged the private adoption that brought her Ashleigh. Though many commentators, and even the trial judge, John Grady, questioned her motives—did she hope that being a single mom would reduce a prison term?—her friends and family insist she just wanted to be a mother. "[Betty] never thought she would be indicted, much less convicted and locked up," says her sister, Pat Rand. "I think she just wanted someone to love and love her back."

Today, Judge Grady's comments still hurt. "To bring up Ashleigh and say the horrible things he did was crossing the line," Betty says. "I'd do a lot of things over if I could. I wouldn't have gotten involved with Frank or Cicero politics, but adopting Ashleigh is the best thing I have ever done."

Ashleigh's birth father worked for the town. He and his wife had other children, but they faced financial problems, and their marriage was breaking up. Betty was in the hospital room when Ashleigh was born, and she took Ashleigh home when the infant was just a few days old. Kitty and a babysitter cared for Ashleigh while Betty was at work.

Eventually, Kitty and Ashleigh moved to Las Vegas, into a house Betty had bought in 2000. Located in a gated community on a small lake, the hacienda-style home has a backyard swimming pool and four bedrooms. Betty commuted back and forth to Cicero. Prosecutors later argued at her sentencing that when Betty was in Las Vegas, she spent more time gambling than parenting. But Betty has always insisted that she went to the casinos only when Ashleigh was in bed or at school. Those who know them insist that mother and daughter have a strong bond. "When I heard about Ashleigh going on the Internet, I wanted to write her a letter and tell her how much her mother loved her, but she wouldn't know who the hell I was," says Mary Lynn Chalada, the former Cicero director of code enforcement.

Betty never told Ashleigh that she had been adopted, and she hoped she wouldn't have to tell the girl the truth about prison. She had used the remaining half million dollars in her campaign fund to hire the renowned appeals lawyer Alan Dershowitz, of Harvard Law School, and she was confident she could stay at home on an appeal bond while he worked to overturn her conviction.

In January 2003, Judge Grady sentenced her to eight years in prison and ordered her to repay $3.25 million, which was determined to be her share of the theft. A few weeks later, saying he was concerned that Betty might gamble away the money she owed the government, Grady ordered her to report to prison two months ahead of schedule, six weeks before the special party Betty had planned for Ashleigh's sixth birthday.

In those final days before she went to prison, Betty agonized over what to say to Ashleigh. She talked to a leading child psychiatrist, who advised her to tell Ashleigh the truth. Instead, Betty says, she listened to friends from Cicero who argued that Ashleigh was too young to understand. Betty convinced herself that she would win her appeal and soon be home. On the morning of her departure, she told Ashleigh she was leaving town for work, as she had done previously. Ashleigh seemed to sense something wasn't right. "Where's your suitcase, Mommy?" she kept asking. When Betty started to cry, Ashleigh ordered her to stop.

The system first assigned Betty to a minimum-security prison in Dublin, California, about an hour from San Francisco. When Ashleigh came to visit, Betty told her that the prison was now where she worked. In the summer of 2004, Betty asked to be transferred to the prison camp in Victorville, in the desert around 100 miles northeast of Los Angeles, closer to her Las Vegas home. It was a mistake. Dublin offered an outside area for children to play. Victorville has only a grim visiting room. The drive back and forth was hard on Kitty, and Ashleigh hated the place. They still talked with Betty on the phone every night, but they visited less often.

Although Betty frequently told Ashleigh she hoped to be coming home soon, Ashleigh began to suspect her mother wasn't just working away from home. Last June, four and a half years after Betty went away, Ashleigh used Google to learn her family secrets. On the phone later with her mother, years of anger and confusion came pouring out. Betty says Ashleigh told her she would throw the newspaper articles at her when she saw her and said Ashleigh yelled, "I want away from this friggin' family." She said Ashleigh wanted to find her birth mother.

Phone time is limited for the inmates and Betty had just minutes to explain a lifetime of lies to Ashleigh. The angry phone calls continued. Betty says she kept telling Ashleigh, "No matter what you say, I love you."

Betty knows she made a big mistake. "I should have told her the truth. I just never thought I would be here this long. I understand why she's so angry. I hate it when people lie to me, too."

A few months before the crisis with Ashleigh, Vrdolyak said a "little bird" told him the government was getting ready to seize the Las Vegas house as part of Betty's forfeiture, according to Betty's family. Vrdolyak started sending smaller checks. Betty exploded with anger. She claims her mother was so strapped for cash, she and Ashleigh were eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for dinner. She loves the house and says it's her only asset.

Vrdolyak wouldn't answer her letters. "I am sick that Ed is doing this to me at this time," Betty e-mailed friends. "Realtors are coming to the door telling my mother the house is going into foreclosure. She sounds weak and scared. His assets aren't frozen. Why is he doing this?"

But Betty's sister, Pat Rand, doesn't think Vrdolyak was trying to hurt the family. "He was very concerned about my mother and Ashleigh being alone in Las Vegas," Pat says.

For several years, Pat had been pushing for Kitty and Ashleigh to come live with her in the South. Betty always said no. She didn't want them so far away, and she worried about losing Ashleigh forever. Just 16 months apart in age, the sisters say they have never been close. After being estranged for years, they reconciled before Betty went to prison. Until last year, Pat made phone calls and sent e-mails for her sister. She took Ashleigh and Kitty to visit Betty and sent her sister money. But Betty got angry that Pat—who has her own home and family—wouldn't move to Las Vegas and stay with Kitty and Ashleigh. The two sisters haven't talked in a year.

Pat says that by last summer the Las Vegas house had become a prison for Ashleigh and Kitty. They have only one close friend in Las Vegas. Kitty did not feel comfortable driving around the city. There were no kids in the neighborhood for Ashleigh to play with. Sometimes Kitty grew so exhausted in the evening, she would go to bed by seven, and Ashleigh would stay up watching TV or playing computer games. In May, Kitty had cataract surgery and it didn't go as well as hoped. Driving is out of the question.

Everything came to a head when Ashleigh learned the truth. Betty wanted Vrdolyak to hire a caretaker to help her mother. She wanted to get counseling for Ashleigh and keep her in her private school. Vrdolyak held firm and cut back on the financial help. He agreed with Pat that Ashleigh and Kitty needed to go live with her.

In August, just days before school would begin, Ashleigh went to live with Pat, but Kitty remained in Las Vegas. The sisters weren't reconciled. Betty was devastated that Ashleigh was leaving, and Pat was furious that Kitty was staying.

Betty says she acted on Vrdolyak's recommendation in hiring Terry Gillespie, one of Chicago's most highly regarded defense attorneys, to represent her at her trial. In practice, though, Gillespie's courtly and genial style was never aggressive enough for Betty's liking. She thought he was too pessimistic, and she wondered whether he was more interested in keeping Vrdolyak off the stand than in defending her. (Gillespie is now on Vrdolyak's defense team in his criminal case.)

Today, Gillespie says he still thinks Betty is innocent. As for how they got along, he says only, "She wasn't a shrinking violet."

Betty says she hired Alan Dershowitz for the appeal because she wanted someone with no ties to Vrdolyak. Dershowitz disappointed her, too. She never met with him in person, and when he argued her case before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, he continually mispronounced her name, calling her "Loren Mal-TEE-zee." The court denied the appeal in 2005.

Her new lawyer, Leonard Goodman, serves on the advisory board of Northwestern University law school's Center on Wrongful Convictions and on the board of DePaul University College of Law's Center for Justice in Capital Cases. Out of money and desperate to continue her legal fight, Betty asked Vrdolyak to pay Goodman a fee to look at the case. "I was pleasantly surprised to see how slim the evidence was against her," Goodman says. In the beginning Vrdolyak paid Goodman's fees, but Betty soon worried about Vrdolyak's involvement in her case. "He never does something for nothing," she said at the time. Goodman then canceled the fee agreement with Vrdolyak but continued to represent her.

Last summer, Goodman filed a motion for a new trial with Judge Grady, arguing that Gillespie had provided ineffective counsel. The heart of the argument is that at a town board meeting in October 1996, Betty ordered the town treasurer, Joseph DeChicio, to stop sending payments to Specialty Risk Consultants, the insurance company—an indication that she was fighting the scam, not participating in it. But the board minutes that would corroborate her action were never admitted in court because of questions about their authenticity. Goodman argues that Gillespie didn't try hard enough to substantiate them. Goodman says he has affidavits from four people, including two town board members who state that Betty did order a halt to the payments. (DeChicio was the only defendant acquitted at the trial.)

In November, Judge Grady rejected the motion, saying he still didn't believe the minutes were legitimate. Goodman filed a motion asking the judge to reconsider. He included a statement from DeChicio's former assistant who says DeChicio handstamped Betty's signature on the wire transfers to the insurance company without her knowledge, even after he had been told to stop, according to some board members. The judge remained unconvinced.

"We could have had Jesus Christ come into the courtroom and say Betty was innocent, and Judge Grady wouldn't have changed his mind," says Goodman. He insists he's not giving up, but shortly before Christmas, Judge Grady ruled that Betty could not appeal anymore. Goodman is appealing that ruling too, but if he loses, Betty's legal fight is over.

"Her chances are slim," says Leonard Cavise, a professor at the DePaul University School of Law. "Ineffective counsel is one of the toughest legal arguments [to make]," he adds, especially when lawyers have kept this case alive in the courts years after her conviction. "She was convicted by inference—the well-connected mayor of a mobbed-up town knows what's going on and is probably in the middle of it. That was a short inferential jump for the jury to make."

The Victorville prison camp sits in the middle of the Southern California desert. Betty has few visitors. E-mail is her lifeline to the outside world. Many of the other prisoners are young and Hispanic, serving time for drugs. Betty works as a mentor and says she has made friends. They call her "the Mayor." But the prospect of two more years there is something she tries not to think about. Recently she was reassigned to kitchen duty—"the worst job in the prison," she said in a recent e-mail. "I spend eight hours a day standing up scrubbing pots and pans." In another e-mail she wrote, "I can see why there are so many suicides in prison."

Some of her coconspirators have had their sentences reduced and are already out of prison. She lost her chance for that at her resentencing hearing in 2006 when she refused to apologize to Judge Grady for her role in the fraud. "I am sorry it happened on my watch, but I will not apologize for something I did not do," she told me. "The government knows I didn't get anything from the scam."

If she serves her full sentence, she will be 60 when she gets out. In Cicero, where the mob has been entrenched for decades, some people remember that the town was cleaner and safer when she was in charge. At Christmas, Betty gets so many cards from Cicero residents that the prison guards tell her she needs her own ZIP Code. Some law enforcement officials worry that she could make a political comeback and be more powerful than ever.

But she says no. "There are two things I know for sure: I will never be a virgin again, and I will never get involved in Cicero politics again. There are a lot of good people there, but I will never go back. It would be too dangerous." She has always said she's afraid of the street gangs, not the mob. But many people wonder.

Her relationship with Ashleigh is improving. They talk on the phone each night and e-mail each other. The ten-year-old has made friends in the new town and is working with a school counselor. She recently made the honor roll at school. Betty sent an e-mail to friends: "I am sooooooooooooooooooooooooo proud!"

In a phone call, Ashleigh told me that she has forgiven Betty and no longer talks so much about finding her birth mother. "I love my mom. I know she didn't want me to think badly of her. I think she was double-crossed; she should have had a video camera in her office." Ashleigh knows Betty lost her appeal in December and may not be home for another two years. "It's been so long since I have seen her," Ashleigh said. "I miss her so much."

Friends took Kitty to visit Betty in mid-December, and they celebrated Betty's 58th birthday in the prison visiting room. Kitty left with six boxes of Pokémon cups, plates, and bowls Betty made for Ashleigh for Christmas in ceramics class. But family and friends later became alarmed when Betty turned incommunicado during the holidays. For almost two weeks, no e-mails or phone calls, not even to Ashleigh on Christmas. They didn't know whether she was ill, depressed, or upset because their birthday cards to her had been delivered late. It turned out she had run out of cash in her monthly account and didn't have money to call or e-mail.

Although Pat and Betty still don't talk, Pat hopes she can take Ashleigh to Victorville soon. Money is tight. Pat is retired from the phone company and lives on a fixed income. Vrdolyak has called several times to check on Ashleigh and has talked to her. He continues to send Kitty a monthly check and is paying the mortgage for now. "Ashleigh is doing much better," he says. "I'll always help Betty and the family. When Betty gets out I'll buy her a new house, set up a fund for Ashleigh's education, whatever is needed."

Betty says she's not counting on it. She figures she's on her own and doesn't know what she'll do. "It will be almost impossible to start over at age 60," she says. "The damage done to my mother and Ashleigh can never be reversed. The nightmares of prison will never go away." Maybe she'll stay in Vegas, maybe move to Indiana, where she and Ashleigh had a weekend house years ago. But Ashleigh is happy now in the South, so maybe she'll go there.

It's hard to imagine Cicero's Betty Loren Maltese in a Southern town, but that's where she started out, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Betty says that around the time of her birth, her father tried to unionize the restaurant workers there. It created an uproar, and she says her parents were run out of town, escaping in the middle of the night with nothing but their two daughters and their car.

Fifty-eight years later, the drama continues for Betty. Maybe writing a book is her best bet. As she says, she has a lot more story to tell.