By the early ’90s, local music producer Steve Albini had built a reputation as an abrasive advocate for underground bands, railing against major producers and labels, their royalties, and the commercialization of music. So when he signed on to produce grunge juggernaut Nirvana’s third studio album, In Utero, many of his followers wondered if he was committing his own cardinal sin: selling out. Undeterred, Albini proceeded to record it, only to find that Nirvana’s label, DGC Records, and the band itself later rejected his signature lo-fi sound and remixed much of the critically acclaimed album. With one job, Albini’s rock-solid reputation was suddenly up in the air, and with it his plans to build a revolutionary studio, as Mark Jannot wrote in his 1994 Chicago story “Sonic Youth.”

He’s being squeezed from top and bottom, he says — anathema to major labels and scorned as a sellout or considered newly unapproachable by the punk nobodies who are historically the bulk of his business. “I’m doing less work and less interesting work than I was a year ago,” he says. “And if that trend continues there’s no chance that I’m going to be able to buy a recording studio.”

Jannot’s feature was published in the May issue of that year, meaning it was likely sent to the printer days before Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain was found dead on April 8 from a self-inflicted shotgun wound. In Utero would be the band’s final album. Despite Albini’s fears, he opened his recording studio, Electrical Audio, in Avondale in 1997 and continues to be a sought-after producer.

Read the full story below.

Sonic Youth

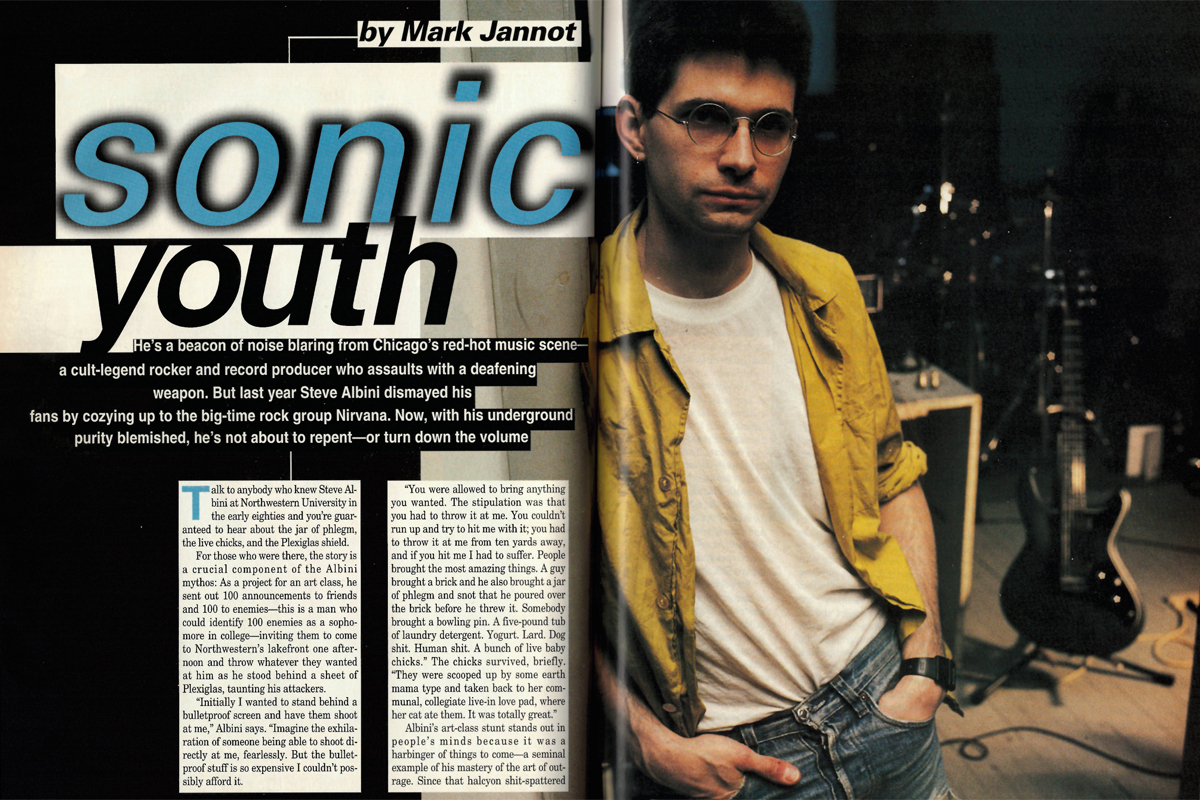

He’s a beacon of noise blaring from Chicago’s red-hot music scene — a cult-legend rocker and record producer who assaults with a deafening weapon. But last year Steve Albini dismayed his fans by cozying up to the big-time rock group Nirvana. Now, with his underground purity blemished, he’s not about to repent — or turn down the volume.

Talk to anybody who knew Steve Albini at Northwestern University in the early eighties and you're guaranteed to hear about the jar of phlegm, the live chicks, and the Plexiglas shield.

For those who were there, the story is a crucial component of the Albini mythos: As a project for an art class, he sent out 100 announcements to friends and 100 to enemies—this is a man who could identify 100 enemies as a sophomore in college—inviting them to come to Northwestern's lakefront one afternoon and throw whatever they wanted at him as he stood behind a sheet of Plexiglas, taunting his attackers.

"Initially I wanted to stand behind a bulletproof screen and have them shoot at me," Albini says. "Imagine the exhilaration of someone being able to shoot directly at me, fearlessly. But the bullet-proof stuff is so expensive I couldn't possibly afford it.

"You were allowed to bring anything you wanted. The stipulation was that you had to throw it at me. You couldn't run up and try to hit me with it; you had to throw it at me from ten yards away, and if you hit me I had to suffer. People brought the most amazing things. A guy brought a brick and he also brought a jar of phlegm and snot that he poured over the brick before he threw it. Somebody brought a bowling pin. A five-pound tub of laundry detergent. Yogurt. Lard. Dog shit. Human shit. A bunch of live baby chicks," The chicks survived, briefly. "They were scooped up by some earth mama type and taken back to her communal, collegiate live-in love pad, where her cat ate them. It was totally great."

Albini's art-class stunt stands out in people's minds because it was a harbinger of things to come—a seminal example of his mastery of the art of outrage. Since that halcyon shit-spattered afternoon on the shores of Lake Michigan, Albini has gone on to achieve international infamy as a punk-rock musician, producer, and philosopher. In the mid-1980s, he fronted the pioneering post-punk band Big Black, whose pursuit of the frontiers of noise is legendary. For a decade, he has spewed streams of bile into the pages of various rock-music fanzines—and into the faces of any less pure wannabes stupid enough to ask him for his honest opinion. And he has become the pre-eminent punk producer of his day, recording, in the past ten years, nearly 1,000 records for underground bands like the Didjits, the Jesus Lizard, Tar, and Superchunk, and surfacing occasionally to bless such major-label acts as the Breeders, Pixies, and PJ Harvey.

Impressive credentials for a 31-year-old Northwestern journalism grad from Missoula, Montana, to be sure. But those are just the trappings: Albini's lasting influence springs less from what he's done than from how he's done it. Through a combination of his strict adherence to an uncompromising underground moral code, and his own brilliant ability to trumpet that personal purity to the world, Albini stands as the music industry's avatar of opposition, its icon of iconoclasm. "I want to do things in a way that is consistent with my personal philosophy of independence, self-determination, absolute total honesty, and common sense," he says. But it's far more than that: Albini sweats buckets over the actual drawing of the lines, and the cataloging of who has crossed them and who hasn't. Much of what he says and writes is devoted to explicating the two camps—those beyond reproach versus those beyond redemption. "It's in the same manner," he says, "that you would want to know, if you were voting for a politician, whether he represented darkness or light, as it were."

Albini's iconoclastic pedigree fueled rumors in mid-1992 that he would be tapped to record the follow-up album to Nevermind, the phenomenally successful major-label debut by the Seattle band Nirvana. But that very pedigree made Albini arguably the worst possible candidate for the job. In Albini's world, nothing marks you as a sellout more starkly than your signature on a major-label contract. Not only had Nirvana crossed over, but by its unexpected ascent to the top of the charts it had pied-pipered a whole crop of underground bands into the grasp of major recording labels. In some ways, Nirvana was the very symbol of all Albini dearly loathed.

So when rumor turned to reality last year, when Albini actually signed on to produce Nirvana, the stage was set for a combustible collision of the underground and the industry. By the time the ensuing furor died down, Albini probably felt again as if he'd been pelted with snot-covered bricks and shit. Only this time he wasn't laughing.

Steve Albini is famously emaciated—it's the first thing you notice about him as he trundles from room to room of his Northwest Side bungalow, hands stuffed deep in the pockets of his worn black Levi's, head pitched forward as if he were on some other physical plane. His legs and arms, clothed loosely in his Levi's-and-T-shirt uniform, are all straight lines and sharp angles, like a stick figure. His face is gaunt under a sad old fedora and behind a pair of wire-rimmed glasses. He doesn't smile much.

The second thing you notice is that when he talks about music or about the record industry or about anything that remotely involves his carefully structured ethical code, the distinctions between what he admires and what he hates can be so fine as to seem almost meaningless. This hairsplitting logic, though, defines Albini's worldview.

Take, for instance, his views on the moral weight of rock music. "The ways by which [musicians] go about what they do and the reasons they have for doing it are every bit as important as what notes they play or what syllables come out of their mouths," he says. "There is a larger context within which music exists, and pretending that it doesn't matter, simply because it's convenient for certain ethical transgressions to take place, is ridiculous."

For Albini, such transgressions are myriad—signing with a major label, altering your music in order to gain popularity, screwing your friends in the name of success. And any one is just cause for dismissing the entirety of the band's output.

For proof of how uncompromising he is on this point, check out his logic on Crane and Rodan, two obscure bands from Louisville. Albini has worked with both bands. Both, he says, sound very much like an enormously influential band called Slint. "But Crane were an utter nuisance and very tiresome and it was obvious that their motivation was not very pure, that they were aping Slint stylistically," he says. "I would not enjoy listening to a Crane record. Rodan, to me, seemed much more organic, much more personal. The fact that their music stylistically is almost identical really means very little."

In other words, one band is imitating Slint, and the other is just approaching its music from a Slint-like perspective. And although no one else might be able to tell their records apart, in Steve Albini’s eyes Crane sucks and Rodan rocks. One is pure. The other should be dismissed.

For Albini, you see, listening to music is more a theoretical than an auditory experience. Style is not substance, style is just style. Actions and ideology are substance. His is a tough world to inhabit, one ruled by a philosophy that's hard not to pervert.

It's a worldview he began developing at a very early age.

In a lot of ways, you spend the last 50 years of your life trying to get over the first 12.

—Steve Albini

“I'm living exactly the way I wanted to when I was a kid," Albini says, and he doesn't mean that he's living in a treehouse, staying up all night, playing with lots of nifty toys, and avoiding contact with adults and girls. (Actually, he does live that way, but that's not what he means.) What Albini means is that he developed the germ of his worldview at about age 12, and has lived it unflinchingly ever since. "I was emotionally very unstable when I was younger. When I was 12 to 14 years old I felt very put upon by the world around me, and I had bouts of depression. I felt the need to stabilize and solidify my perception of the world at a very young age. And I did, and I sort of stuck to it."

As Albini recounts it, that emotional instability arose from a remarkably unremarkable homelife in the college town of Missoula, Montana. Albini's mother, Gina, is an archetype of a Rockwellian caregiver. Twice a year while her children were growing up, at Christmas and Easter, she would open her dinner table to serve a meal to the parolees who were working locally on forest-clearing crews. When her two eldest children left for college, and Steve was about 16, she began bringing in Vietnamese and Laotian foster children. His father was the first of his line to complete any kind of formal schooling, and overcompensated by graduating at the top of his class at Cal Tech and earning doctorates in mathematics end aerodynamics and a master's in philosophy. As a world-class authority on the mathematical modeling of forest fires, Frank Albini was described as follows by Norman Maclean in his book Young Men and Fire: "In addition to being a brilliant scientist, he turned out to have a quiet, persuasive literary style that helped to make him an effective, half-concealed salesman for the extended use of mathematical models in the woods."

"When my birth certificate was filled out, my dad, being the anal completist that he is, could not leave the middle-name section blank," Albini says. "Strictly speaking, I have a middle name, but my middle name is `(None)'."

It was a classic parental dichotomy. "My mom was a very, very loving and motherly mother," Albini says. "That's really the only way to put it." And his father was just the opposite: distant, detached. "I sort of feared him, even though there was no cause for me to be afraid of him. He just sort of didn't take us seriously as people when we were kids. And due to the fact that we were kids, I don't really blame him. But I think that probably the way to make a kid happiest is to treat him like a person and take him seriously. That was a leap that my dad wasn't able to make."

Of course, millions of children of Albini's generation grew up with emotionally absent fathers, but Albini seems to be the preternaturally sensitive sort who felt the effects more acutely than others. In any case, by his early teens he was a borderline emotional basket case. And in that fertile adolescent soil his obsessive iconoclasm took root. "I felt that everybody else in the entire world had his shit together and I didn't," he says. "And everybody else in the world was respected and appreciated and I was not. And almost like a curtain opening, I realized that as soon as I stopped giving a shit about what other people thought of me, all of those other problems would go away. And, like that, it happened. It was as obvious as opening a door to go through it. It's an exhilarating freedom that you have when you don't care if people like you or not."

An excerpt from the liner notes to Pig Pile, a live album recorded during Big Black's last tour:

It meant nothing to us if we were popular or not, or if we sold either a million or no records, so we were invulnerable to ploys by music scene weasels to get us to make mistakes in the name of success. To us, every moment we remained unfettered and in control was a success. We never had a manager. We never had a booking agent. We never had a lawyer. We never took an advance from a record company. We booked our own tours, paid our own bills, made our own mistakes, and never had anybody shield us from either the truth or the consequences. The results of that methodology speak for themselves: Nobody ever told us what to do, and nobody took any of our money.

Big Black was born in December 1981 in the living room of Albini's student apartment. Albini had been in two bands during his first couple of college years, a garage band called Small Irregular Pieces of Aluminum and a prominent local skinny-tie New Wave band called Stations, which kicked him out when he started trying to push their music in the direction of the train-wreck apocalypse that would be Big Black. "He had this really unusual bass sound that nobody else had," says Bob Orlowsky, who sang with Albini in Small Irregular Pieces of Aluminum and later moved out of the apartment they were sharing because, among other things, he couldn't stand the way Albini answered the phone with an angry "Fuck you!" all the time. "He'd wrap these cords around his waist and the bass so there was nothing interfering with his arms. It would wobble and he'd have the treble turned all the way up to ten and the bass turned down to zero, so it was this incredibly tinny, buzzy bass sound. He kind of played it like a guitar, too. He wasn't into rhythm so much as he was into sound."

By the time he was sacked from Stations, Albini couldn't find anyone who was into sound in quite the way he was, so he recorded the first Big Black album, Lungs, on a borrowed four-track tape deck, playing all the instruments himself. "It was completely unlistenable," says Santiago Durango, a founder of the seminal Chicago punk rock band Naked Raygun, who soon signed on to play guitar in Big Black. "That's one of its saving graces—that it's probably the worst piece ever put together by a human mind. It's horrible. But it's so horrible that there's something there. It transcends horrible."

Lungs was designed as a calling card: "I thought, Well, if I put out this record, that will give people the idea of what kind of music I want to make and then I'll be able to find people who want to be in a band with me," Albini says. "It worked." Jeff Pezzati, Naked Raygun's singer, soon joined Big Black on bass, and Durango followed. Albini sang and tortured the guitar, and a tireless, pounding drum machine named Roland rounded out the noise. After two more records, Pezzati left the band and was replaced by Dave Riley, who'd done time with a band called Savage Beliefs.

For a trio of anti-industry curmudgeons, the members of Big Black posed for an awful lot of photographs. Wearing fedoras and wire rims and serious stares, they peer out from these old black-and-white shots—murkily photocopied from valedictory articles extolling the blind fury and negating passion of Big Black—like three stolid Hollywood gentlemen farmers who've come to town to pick up some chaw and some feed at the general store. Intense workers from the heartland, solid family men. Their music was something else entirely.

Big Black's noise drove rock fanzine writers to metaphoric rapture. Sonic word pictures streamed from their fingers, trying desperately to compete with the assault they were hearing. In 1986, Albini trumped them all by writing his own unrelenting evocation of the Big Black sound (so unrelenting, in fact, that the following expurgated quote is a pallid shadow of the original, which appeared in Forced Exposure magazine): "I don't give two splats of an old negro junkie's vomit for your politico-philosophical treatises, kiddies. I like noise. I like big-ass vicious noise that makes my head spin. I wanna feel it whipping through me like a fucking jolt. We're so dilapidated and crushed by our pathetic existence we need it like a fix. … Big Black is a way to get the blood boiling without having to … hang around slaughterhouses. It's as simple as that. I want to push myself, the music, the audience and everything involved as close to the precipice as possible."

The lyrics, which were never the point (and which were often buried so deep in the mix that they were almost indecipherable anyway), probably got too much attention during the band's five-year existence, and garnered Albini a large chunk of his antisocial aura. Suffice it to say that they were little mini-documentaries about the perverse side of life in these United States: pedophilia, wife beating, frequenting and (possibly) immolating the town whore, murdering your retarded newborn. "Jordan, Minesota" is an account of a notorious mass-incest case. Anyone who wants to interpret its lyrics—"This is Jordan / we do what we like / This is Jordan / we do what we like / Stay with me / my five-year-old / stay with me / play hide and seek / And this will stay with you until you die / and I will stay with you until you die / And this is Jordan / we do what we like"–as some kind of glorification of child sexual abuse is entitled to his opinion.

The band broke up in 1987, near the height of their popularity, so that Santiago Durango could go to law school. They left a twofold legacy—sonic and psychic. "Unfortunately, the bad influences have been a million sound-alike bands that have watered down the Big Black thing and in some cases made a lot of money doing it," says Gerard Cosloy, co-owner of Matador Records, who knows Albini from when they were both writers for Matter magazine in the mid-eighties: "The positive influence comes from the fact that Big Black followed what they wanted to do. They conducted their business with dignity and honesty; they stuck to their guns; they broke up before they began to suck. They set a terrific example that most of these nineties bands just can't live up to."

A set of raw wooden shelves set into a nook just off the kitchen in Albini's house holds a sparse collection of banal household items: a full shelf of individually wrapped rolls of toilet paper, a family-size box of Pop Tarts, and a smaller package of Knox gelatin. A few steps away, on the wall of the living room, hangs a painting of a young woman, her upper body transparently clothed in a filmy negligee. Press on her right breast and the shelves slowly rise, revealing a set of stairs leading up to Albini's personal recording studio.

The black cloth walls of the studio slope to a peak for better acoustics. (With flat walls, sound would bounce back and forth from wall to wall.) Track spotlights shine down on an impressive variety of state-of-the-art analog recording equipment: a 24-track tape deck, a 36-channel recording console, stacks of cassette decks, something called a dual trace oscilloscope that visually displays the electrical properties of sound as a dancing green mass of sharp geometric shapes. "It's just another form of metering that has certain specific applications," Albini says. "But mostly it just looks good. I usually refer to it as the video, as in, 'Oh, that band has a really good video.'"

This, the recording studio, is Albini's bailiwick now, and has been more or less full-time since the breakup of Big Black in 1987. "All I want to do is, I want to make records that sound realistic and that kick my ass," he says. "Everything else is secondary to that." He spends half a day or more setting up microphones and tweaking sound levels. Then, while the band plays, he sits in a rolling desk chair, sliding from one piece of equipment to another, twisting the occasional knob. "The lion's share of the job is deciding what to do with the microphones," he says. "I'll take 30 mikes with me when I go out of town. It's unusual for another engineer to even own a microphone. I consider that the equivalent of a violin player who does not own his own bow."

And what Albini does with his microphones, what he's renowned for, is arrange them copiously and precisely around the drummer. He's a disciple and chief missionary of a recording approach that has swept underground and alternative rock circles and that has come to be known as lo-fi—an ironic name for a style of recording that's designed to maintain the highest fidelity to the band's actual sound, to produce a recording that's as "live" as possible. In one sense, it's hardly "producing" at all, which is one reason Albini prefers the title "recording engineer." His function, as he sees it, is to be a clear window, transferring the band's sound intact to vinyl or disc. The hallmarks of the Albini sound are a well-balanced interrelation among all the instruments, vocals that assume equal footing with the music instead of floating above the mix, an extraordinarily wide stereo stage (your right ear hears something completely different from your left), and a pristine, echoey drum.

"His drum sounds are legendary. I've been trying to rip him off for years," says Brad Wood, who has produced recent breakthrough Chicago alternative acts Liz Phair and Red Red Meat at his Idful Studio in Wicker Park. "He finds a good space, puts a drummer in it, and then records the sound of the drum in that space, without a lot of crap."

This attention to unerringly capturing the dynamics of live performance has led Wood, among others, to make what, on its face, sounds like a particularly absurd analogy for the kind of recording Albini does. "I think Steve ought to be recording classical music," Wood says. "I think that's where he's headed sonically. His pursuit of sonic excellence is getting to the level where he could go toe to toe with the great engineers who do these major recordings of giant orchestras."

Albini demurs, although he's flattered by the comparison. "I don't really have any interest in and I don't really have any understanding of music like that," he says. "I understand rock bands and I understand the physics and technology of making good recordings. So that's the kind of music I work on and that's the way I go about it." And he doesn't see any irony in the fact that he's making pristine, sonically beautiful recordings of bands that are, in many cases, simply making noise. "I consider that me doing a good job," he says. "I honestly just feel that music like this deserves to be taken seriously. And that means people who record them should be as concerned about quality as if they were recording the fucking Chicago Symphony."

Albini has an acute belief that his methods—and his prices—can be the greatest thing to happen to the small-fry, full-throttle punk rock bands that are his bread and butter. And he makes every attempt to accommodate as many as possible. "I try not to turn down anybody who comes to me desperate, with no other options, people who have no money and have no hope of making a record in any other way," he says. "There is literally no other place in the world where you can make a record of this caliber, using this caliber equipment in a studio of this caliber, with a guy like me—a guy that's made hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of records as the engineer—for any less money."

That goes double for the occasional major-label bands that solicit his services, bands that would typically expect to pay a name producer a flat fee plus "points"—royalties—on the retail price of every album sold, a ubiquitous practice that, if the record hits big, can add hundreds of thousands of dollars to a producer's take. Unlike just about any other big-name producer, however, Albini scorns the practice. "I think anyone taking a royalty on a record who did not write music and sing songs and play instruments and load equipment into a van and spend five years putting up with a whining, miserable drummer—anybody who's not in the band who's earning a royalty on a record is a fraud," he says. "Royalties belong to the artist. Period. A producer who takes a royalty on the record is a thief."

When rumors started to circulate that Nirvana would hire Albini to record its second major-label album, In Utero, it seemed to make sense. Nirvana was a band that had arisen from the ashes of punk, that was weaned on the same do-it-yourself ethos that is Albini's stock in trade, that fancied itself to be too specific and too extreme ever to be truly popular, and that had somehow emerged through some wormhole in the Zeitgeist to produce Nevermind, the top-selling album of the nascent nineties with more than eight million copies sold worldwide. Soon Seattle was the hippest place in the world; "grunge" was such a force that it was quickly co-opted by New York and Paris couturiers, who clothed their runway models in flannel, wool skull caps, and combat boots; and "alternative rock" was such a hot marketing niche that it spawned its own backlash, inspired by the self-evident question: "Alternative to what?" And just as soon, the members of Nirvana—most crucially the band's singer, songwriter, and world-famous heroin user and malcontent, Kurt Cobain—were looking for a way to reclaim their underground credibility.

The obvious choice to produce the next album was Steve Albini. But for the longest time it was just a rumor. For months Albini was pestered with calls to congratulate him, condemn him, or simply confirm the news—and he hadn't heard word one from the Nirvana camp, or from Geffen, the band's label. But, according to an old roommate, a Chicago booking agent who goes by the name Boche, Albini kept a lid on the news even after he had made the deal—for $100,000 and no points. "He outright denied it to me over and over again after I knew from Nirvana's management and someone from the label that he was doing the record," Boche says. "I would call him up just to give him the opportunity to lie to me. He did it three times."

And no wonder. It was simply unimaginable to many fellow travelers that Albini would consent to produce an album by such a huge-selling major-label act, no matter how strong a case could be made for the underlying integrity of the band. "A lot of people call him a hypocrite for doing the Nirvana record," says John Mohr, a friend of Albini's who sings in the band Tar. "Someone who's talking down major labels as scum and then doing this Nirvana record, you've got to wonder."

Albini's strident criticism of major labels and, by extension, any band stupid enough to sign to one is legendary. In an article titled "The Problem With Music" in a recent issue of The Baffler, a pop-culture lit mag published by students at the University of Chicago, Albini meticulously examined the economics of the music industry, concluding that even a putatively successful band, propelled by the full push of label promotion, is likely to end up with nothing but small change in its pockets and a host of headaches for its troubles. "Some of your friends are probably already this fucked," he concluded, in bold print.

But it's not just that he thinks that underground, uncommercial rock bands that sign to major labels are stupid; he thinks they're sellouts as well. Albini's definition of selling out is stark: "Doing things that you yourself would disapprove of under different conditions, in the hopes that it will increase your stature." And is signing to a major label a de facto sellout? "It depends. For example, if you see a guy lying on the floor with a bullet hole in his head, is that a sign that he was shot? Well, most of the time, but not always. It could have been that a meteorite precisely the size and shape of a bullet hit him in the head. A band making a move to a major label has convinced itself it is doing so for specific reasons. If those reasons are that it is currently dissatisfied with its status on an independent label and those reasons are valid, I can conceive of a band moving to a major label without being considered a total sellout. Although I have yet to encounter that."

Obviously, this is not a man who would be comfortable serving as the vehicle for a sellout band's credibility infusion. He had to vet Nirvana first. "I made it clear from the beginning that if they wanted me to work on their record it should be for concrete reasons," he says. "If they just wanted to use my name, I wasn't going to permit that. I was convinced from dealing with them that they had an honest, legitimate respect for the records that I've made, and that they wanted me to do that sort of a job for them. And I did."

And that's when the trouble started. Last spring, shortly after In Utero was recorded, Tribune rock critic Greg Kot began hearing rumblings that Geffen executives and Nirvana management hated it—Cobain's vocals were lost in the mix, you could hardly hear the bass, and it was just too damn noisy and uncommercial. Kot called Albini to get his reaction, and Albini, whose philosophy requires brutal honesty, gave it to him.

Here is how Kot's blurb on the front of the Tribune's April 19th Tempo section read: "Nirvana's new album, the most widely anticipated rock release of the year, has been recorded but may never be released by the band's Geffen label. That's the prediction made by the record's producer, Chicagoan Steve Albini. … 'Geffen and the band's management hate the record,' said Albini, known for his harsh, uncompromising production aesthetic. `They considered it an indulgence when Nirvana asked to record with me. I have no faith this record will be released.'

"'It sounds different than any record made this year,' he added. 'It's not a record for wimps.'"

Albini insists that he did not create the uproar that ensued, and in a sense he's right: The journalist called him. But his remarks turned a flaming matchstick into a forest fire. Newsweek followed up with a lengthy account of the apparent feud, commenting archly on the conflict between alternative rock and corporate America; Rolling Stone soon added its voice to the chorus; and before long, when word spread that Nirvana had enlisted R.E.M. producer Scott Litt to remix a couple of the songs, the natural conclusion was that the band had buckled under.

The reality was a bit thornier. It turns out that, almost from the moment they returned to Seattle, the members of Nirvana were themselves unsatisfied with certain aspects of the recording. "As soon as they came back I listened to the tape with them," says Michael Azerrad, a Rolling Stone writer and the band's unofficial biographer. "I was there, and they said, 'The vocals aren't loud enough and we can't hear the bass.' They were thinking this before anybody said anything."

The idea that the band itself was the prime motivator behind the move to remix presents a problem for Albini, who likes to portray himself as the undying advocate for the bands he works with. Ultimately, he extricates himself by impugning the band's credibility. What it comes down to, for Albini, is that Nirvana didn't have the courage of its own (or his own) convictions. "They had a great record on their hands," he says. "And they were so petrified that it wasn't a perfect record that they wanted to do anything possible to ensure that it was at least mediocre."

What they did was not only have a hit-making producer remix two songs for radio, but also completely change the tonal balance of the record during the mastering process, putting a more radio-ready sheen on it. "Ultimately, for whatever reasons, by the time the record was released they were not comfortable with the kind of job that I'd done, and they wanted to fiddle with it," Albini says. "Seeing as how it's their record and their career—if somebody wants to shit in his own soup, it's really none of my business."

This is, for Albini, a measured act of self-justification. By speculating in the media that In Utero would never be released (because it was too uncompromising), and by explaining how his sound was watered down (because it was too uncompromising), he's shoring up any underground credibility he may have lost by taking a hundred grand to record a big-budget major-label blockbuster. As his old roommate Boche says: "He was standing up there proud as a peacock in the press, going, 'Look what I did! I screwed 'em all up! I told them all to fuck off!'"

Albini scoffs. "If someone else chooses to perceive it as me trying to maintain my separation from the industry while working within it, I deny ever having worked within it," he says. "In my life I've worked on fewer than a half-dozen major-label records, and I've probably worked on well over a thousand records in total. In terms of a percentage of my attention, that's how much attention I'm willing to give major labels. And in the end the bills are paid by the band. I'm not working for major label; I never have."

Finally, though, all this sophistry begs a fundamental question: Knowing that he was going to get the kind of flak he's gotten for apparently diving so deep into the cozy embrace of corporate rock, why did Albini agree to record Nirvana in the first place? "It was obvious that they were in a unique position," he says. "They were ripe to be taken advantage of by whoever got involved with them; whoever was allowed to would try to fuck them. This kid wrote me a letter saying, 'I can't believe you're doing this Nirvana record. Why on earth did you do this?' The answer that I wrote him just off the top of my head was: I sort of felt sorry for them."

Early this year, Albini whipped out his poison pen and composed a few dozen lines of arsenic for Reader rock critic Bill Wyman and the newspaper's readership. "The opening paragraph of your Year-in-rock recap is one of the most brilliant bits of ass-forward thinking I've seen in years," he began, and the insults escalated from there: "Look at the shoes you're standing in, big nuts. Music press stooges like you tend to believe and repeat what other music press stooges write, reinforcing each other's misconceptions as though the tiny little world you guys live in (imagine a world so small!) actually means something to us on the outside.…"

He signed off with his trademark "Fuck you."

Wyman's sin? He had dared to tout the three Chicago acts who in 1993 ascended to national rock prominence—Smashing Pumpkins, Liz Phair, and Urge Overkill—not only for their music but for the message that Wyman saw underlying their success: "an explicit rejection of much of the insularity that increasingly characterizes underground music and the fringes of alternative music in America."

Wyman's article never mentioned Albini's name, and to those readers unschooled in the perverse dynamics of the local music scene, Albini's bluster must have seemed a bit paranoid. But they would be wrong. "It was directed specifically at him," Wyman says. "I've wanted to write something for a long time and just call it Albini-ism.'" For Wyman, Albini-ism—the pursuit of underground purity at all costs—represents a rather virulent strain of dogmatic navel-gazing. "Every generation manages to get itself in high dudgeon about the fact that we live in this capitalist world and they try to live in it with moral purity," he says. "It's sweet, but it doesn't matter."

What does matter to Wyman is that, by so carefully and publicly dividing the world into us and them, Albini obscures some of the more practical reasons for bands to sign with a major label. "Small labels have fucked over as many people as big labels have," he says. "And at least when these bands get fucked by the big labels, they get two years of fun in the sun; they get to have a good tour and good sound and publicity and people who get to buy their records in the stores. Nobody talks about the peace of mind of having insurance for two years. This whole major/minor thing is a sham."

If Albini's letter proved anything, it's that he is still as adept as he's ever been at pushing people's buttons. For several weeks afterward, the Reader letters column was dominated by reactions ranging from impassioned to bemused. Many writers questioned the integrity of the moral pedestal on which Albini stood. As one local musician wrote: "Steve, Steve, Steve, why all the bitterness? You blasted against three 'mainstream' bands, but in light of your recent production work with the multiplatinum, critic-adored (like yourself), and 'mainstream' Nirvana, all your erudite spleen purgings stink of hypocrisy.

"It sounds to me like you are pissing and moaning about the meal you have been served after devouring every morsel off your plate."

Last fall, Albini was featured in "40 Under Forty," a Crain's Chicago Business spotlight on up-and-coming young business leaders in Chicago. In the accompanying text, Albini said he was planning to build a new studio in Chicago "so nice and so cheap, you'd have to be stupid to make a record anywhere else." Now, though, after the Nirvana fallout, he says he's not sure he'll ever have the money. He's being squeezed from top and bottom, he says—anathema to major labels and scorned as a sellout or considered newly unapproachable by the punk nobodies who are historically the bulk of his business. "I'm doing less work and less interesting work than I was a year ago," he says. "And if that trend continues there's no chance that I'm going to be able to buy a recording studio."

There are, though, other reasons that bands may be shying away. Some may just be getting tired of his prickly nature and his sometimes domineering presence in the studio. Take, for instance, his pedantic rants while recording Nirvana. "Steve got into these big lectures," says Bob Weston, Albini's second engineer in the studio and the bass player for his band Shellac. "Kurt [Cobain] would say, 'I want to do a guitar overdub,' and Steve would explain to him for a half-hour why it wasn't a good idea, using all these weird technical terms. And Kurt would say, 'Well, that may be so, but I still want to do a guitar overdub.' And Steve would explain to him again why he shouldn't do it, and it would go back and forth. Steve does that a lot to bands. He figures that they hired him for his expertise and they like the way records that he's done have sounded and he's going to tell them what's on his mind, but he's really pedantic about it and really talks down to people, well below their level of intelligence. The last line of any of these lectures is always, 'But you're paying me, so I'll do what you want. I have to put in my two cents because you're hiring me.' But his two cents turns out to be, you know, five hundred dollars."

The Jesus Lizard, a Chicago band that Albini calls the best rock band in the world, and whose lead singer, David Yow, is Albini's best friend, briefly considered recording their latest album with someone else, apparently because they were tired of being berated for trying things in the studio that didn't fit with Albini's ideas of what sounds good.

Albini's obsessive iconoclasm has wreaked havoc on his personal life as well. He talks of having a tight hold on his external, professional life and a loose one on his personal life. "I don't do things for myself first and foremost," he says. "I do things because the things that interest me are trump. Playing music, recording music, reading good books, those things come first. Second would probably be billiards. Third would be the girlfriend. That's always been a problem. No girlfriend in the world would want to admit that she comes third to billiards."

It's a lonely life, the life of the iconoclast. But if anything, Albini shows signs, post-Nirvana, of upping the ante. Witness his approach to recording music with his current band, Shellac. "I wanted Shellac to be a band that behaved in a very responsible manner, a very personal manner," he says. "I wanted everything that Shellac did to have our fingerprints on it. We actually make and decorate by hand the sleeves for our singles here in the house. So far there have been 14,000 of them and there's going to be another 10,000 of them in the next couple of months. It's personal and very rewarding to me to know that everybody that buys a Shellac single is buying a record that was assembled in my house, that we decorated specifically, not that we hired someone to do for us for pennies an hour. We came up with an idea, we executed it, it's us, and they're buying a record that we made.

"I take a lot of pride in the music," he says, finally, "but I also think that it's important that we are not part of an industry."