A Glimpse Into Ware’s Work

|

Illustration: Provided by the Artist

|

|

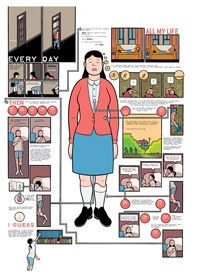

"I do have a self-portrait, which you’re welcome to use, as long as you don’t blow it up; please also make sure it appears completely; i.e. without cutting or "selecting" part of it or anything." "The rather disorienting structure is what I think of as an "exploded" mode of visual storytelling, rather than the more conventional grid of consecutive images through which comics are traditionally threaded. (For this compositional idea I have to credit the amazing artist Richard McGuire, whose strips in Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s Raw magazine changed my life as a young student cartoonist.) I’ve found that the pages I approach in this relational manner (i.e. with no real start or end) practically create themselves in a very strange sort of way." "I draw with non–photo blue Col-Erase pencils, Loew-Cornell synthetic sable brushes, and Dr. Martin’s "Tech" ink on four-ply vellum surfaced Strathmore Bristol board." |

Last year, when The New York Times Magazine decided to run its first serial cartoon, editor Gerald Marzorati selected Chicago cartoonist Chris Ware. It was a smart bet: Ware’s eerily juxtaposed panels-vivid in color yet gloomy in subject matter-had already graced The New Yorker and other publications, won the 2001 Guardian First Book Award, and appeared in the 2002 Whitney Biennial. It seemed that Ware, a native of Omaha and a fixture in Chicago’s comics community since the early 1990s, was poised to permeate the membrane that divides alternative culture from the mainstream.

This month, Ware’s trajectory veers in a slightly different direction, toward high art, with a four-month exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art. To gain insight into Ware’s world, Chicago asked the 38-year-old to take a break from his duties as the father of a one-year-old, Clara-and from his work in the uninsulated attic of his Oak Park home finishing two novels-and explain the intricacies of two panels to be exhibited. Chicago also asked other cartoonists and curators to weigh in on what makes Ware’s cartoons so special, and on what a show like this means for their genre.

Daniel Clowes

Creator of Ghost World and Twentieth Century Eightball (Fantagraphics); South Side native, now a resident of Oakland, California

[About 1991] there were a bunch of cartoonists hanging around Wicker Park. We used to go to Earwax and do little drawings for their menu in exchange for free food. . . . I don’t see the entirety of [Ware] in his work. He seems to fixate on a certain segment of himself. He certainly focuses on the tragic. But I find him surprisingly well adjusted for how one would interpret his work.

Ivan Brunetti

Creator of Schizo (Fantagraphics), Chicagoan, university instructor

The first time I saw his work, I kind of assumed that he was ten years older than I was [in actuality, Ware, 38, is a couple of months younger than Brunetti]. There was such a level of ability with this craft that I assumed he was somebody who had been at it a long time. Over time, it has gotten even more sophisticated. He is dealing more and more directly with core emotional issues. He has gotten more and more in control of the craft, and he continues to experiment with it, but it is always at the service of human storytelling.

Jessica Abel

Creator of La Perdida (Pantheon, April), former Chicagoan, now lives in Brooklyn

It’s important to remember that [Chris’s] work is literature-it’s not purely visual. Readers should read it and engage with it as a work of literature and not just get knocked out by the cool cover design. That’s the problem with an art show. Cartooning clearly is art in the way that a novel is art, or that film is art, or that another medium is art, but it is a medium that is essentially literary.

Gerald Marzorati

Editor, The New York Times Magazine

To me, Chris Ware was an easy call. He is sort of the Picasso and Proust of this graphic novel movement. He has a way of sweeping up everything that came before him and gently referencing it. The way you toggle back and forth between the graphic element and the literary, he has taken that to such a deeper and more experimental level. I really do think he is one of the most interesting artists in any visual medium working in America today.

Eric Kirsammer

Owner of Quimby’s and Chicago Comics

When we moved Quimby’s over to North Avenue [in 1998], I was like, "Hey, Chris, can you come up with an idea for a sign?" He comes by a month later, and he had built a scale model of the front of the store. It was incredible. I couldn’t believe it. The main sign that’s perpenidicular to the building now-that’s his design, the font and everything. The other stuff I couldn’t afford to do.

Commenting on Two Panels

Building Stories; Anatomy, I, 2002

|

Photograph: Courtesy of the Artist

h h |

"This is the first page of a three-page story I originally did for nest magazine in 2003. Though this first page is comparatively mild in its content, it is one of the only stories I’ve ever written about sex, and which was a lot more fun to write than I thought it would be, which is sort of an accomplishment as a repressed, nervous cartoonist."

Chris Ware

"Why is it that we like these characters that represent fragments of a depressed society? We do, I guess, because they represent the survival attitude of the soul, within a society or an historical moment that has put its soul at stake. Chris Ware’s characters represent the America we fear and love at the same time. . . . These individuals are weak but alive, they are miserable but deep."

Francesco Bonami

Senior curator-at-large, MCA

"I had in mind when beginning it those acetate overlay anatomy images which were bound into old encyclopedias and which I found secretly rather smutty as a kid."

"All three of the story pages are arranged . . . with the main character in the center, although the two pages that follow present her stripped of her clothing, and then, on the last page, of her skin . . . though I didn’t really know what this strip would be "about" when I began, it ended up focusing on the dwindling emotion and increasing sexual distance between her and her college boyfriend as their relationship became less and less intimate."

"It’s not told as a direct narrative but as a jumble of memories and associations, the main character peeling back the layers of herself in her mind to try to get to the bottom of why this one relationship ended so badly."

Chris Ware

Excerpt from Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth; Intro, 2000

|

Photograph: Courtesy of the Artist

|

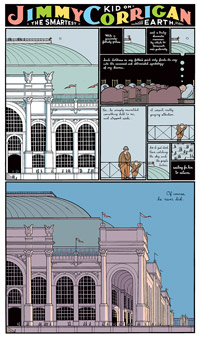

"Once I decided I did want to set part of [Jimmy Corrigan, Ware’s breakout novel] in Chicago at the time of the [1893 World’s Columbian] Exposition (as a contrast to the rather grim blahness of the Chicago of "today") I spent months and years researching. . . . I spent time at the Harold Washington Library looking through their unique documentary archives of the Fair’s construction, bought up or borrowed pretty much every picture or book I could find about the subject, and even work-avoidingly spent a couple of days down in Jackson Park with an antique map trying to determine the relative scale of the grounds. . . . Stupid! Of course, after all this preparation, the final section ended up being little more than ten quick pages, culminating with this selection."

Chris Ware

"Jimmy Corrigan’s sad eyes are looking at the Expo and at the world with pre-melancholic gaze. He looks as if he already knows that to be a real person means to give up any kind of idealism or utopia."

Francesco Bonami

Senior curator-at-large, MCA

"The panel to the left is halved in size to form the top panel and that panel is halved to yield the text and image panel that reads, "So I just stood there, watching the sky and the people below," which is halved to yield the image panel of the distant crowds, which is halved to yield the text panel "waiting for him to return." In what should be an utterly expansive moment, Jimmy’s world constricts and constricts and finally turns black."

"I am always amazed at the emotion he draws on the little cartoony faces, such as [Jimmy] Corrigan’s wonder at being at the World’s Columbian Exposition with his Dad, even as he senses something is terribly wrong, and he is in fact about to be abandoned."

"He seems to be attending the fair in his nightgown . . . remembering it as a semi-hallucinogenic experience."

Lynne Warren

Curator, MCA

"The manufacturer’s building, at that point the largest building in the world. I happily found out later that the World’s Fairs were actually quite convenient places to abandon children."

Chris Ware