|

Photo: Selena Salfen |

Kiyoko Lerner sits in the kitchen of her handsome Lincoln Park home on Webster Avenue and recalls people knocking on the door, asking to see the room.

“I have to explain to them that everything has been redone,” she says, shaking her head and laughing.

The pilgrims are hoping to glimpse an iconic space in the art world, the apartment in the building next door that was home to a curious man named Henry Darger, a tenant of Kiyoko and her husband, Nathan Lerner, a successful designer and photographer. In life, Darger worked as a janitor, had little to no contact with his neighbors, and regularly attended Mass-occasionally several times a day. In death, Darger left behind an astonishing collection of drawings, collages, and watercolors, now considered one of the foremost bodies of outsider art in the world.

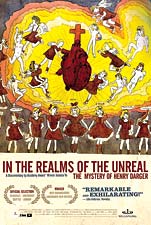

Before he died in 1973, at age 81, Darger gave the works to the Lerners, and over the years, tending the collection came to dominate their lives (Nathan died in 1997). Half a dozen books have been published about Darger and his work. The American Folk Art Museum in New York City has opened a Henry Darger Study Center, featuring pictures and original Darger manuscripts. Darger’s story has been the subject of poetry, an opera, and most recently a critically acclaimed documentary, In the Realms of the Unreal, which was released last year. And, according to Kiyoko, a feature film is in preproduction.

Sales of Darger’s paintings have brought in revenue to the Lerners conservatively estimated in Forbes magazine to be in the low seven figures-perhaps $2 million. But while Darger’s drawings remain in Chicago museums and private collections here, much of his work has been relocated to other cities, particularly New York. Though local museums that might want to acquire more Dargers have been inhibited by the tremendous cost of preserving the fragile material, some Chicagoans think the city has lost a treasure. “The art community in Chicago doesn’t always recognize its own geniuses until they go elsewhere,” says the local dealer Carl Hammer, one of the first gallery owners to sell Darger’s work. “Our artists are much more appreciated by the outside world.”

Meanwhile, Kiyoko Lerner has sold or given away two-thirds of her Dargers, and she is leaving the street where he lived and created his art. “I feel enormous responsibility with all this work, both to Henry and to Nathan,” Kiyoko says, but “I just couldn’t take care of it anymore by myself.”

|

Photo: Selena Salfen |

| A documentary about Darger was released to great acclaim in 2004 (poster, above), and a feature film is now in preproduction. |

Nothing had prepared Nathan and Kiyoko Lerner for the shock of their former tenant’s rise to the status of an icon of outsider art. Kiyoko was born in Tokyo and immigrated to Boston by way of San Francisco; she met Nathan Lerner while on a visit to New York in 1966. At the time, she was studying at the New England Conservatory in hopes of pursuing a career as a concert pianist. Her older sister had encountered Nathan while vacationing in Acapulco and recommended that he keep an eye on Kiyoko. “He certainly did keep an eye on me,” she says, laughing. He made a date to be in New York City when Kiyoko arrived, and they met when he stepped off the train from Chicago. Nathan was doing a project for Maxwell House at the time-in addition to being a photographer, he was also an industrial designer, his most noteworthy creation being the bear-shaped honey dispenser. The two met for breakfast almost every day, were married within a year, and headed back to Nathan’s home in Chicago, where Kiyoko has been ever since.

Nathan lived in a house at 849 West Webster and in 1959 he bought the building next door, where Henry Darger occupied an apartment on the third floor. Other tenants could hear him shouting late at night and arguing with himself. “When he was living here, a lot of younger people started moving in and Nathan felt pressure from the neighbors that he should kick Henry out, because he looked homeless,” Kiyoko recalls. “But he was totally harmless.” The Lerners kept him on, even lowering his rent at one point from $40 a month to $30.

In 1972, Darger’s health problems worsened, and he encountered more difficulty climbing the stairs to his apartment, so the Lerners moved him to a charity nursing home. In his room, they found years’ worth of junk, from balls of twine to towers of papers and magazines-as well as 300 or so drawings, collages, and watercolors, many of them ten feet long and painted on both sides. The works apparently illustrated Darger’s single-spaced 15,145-page novel entitled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. The book describes the adventures of the seven young Vivian Girls, who lead an uprising against murderous men attempting to enslave children. Darger drew penises on many of the girls, giving the works a bizarre sexual subtext.

Other than Darger himself, the Lerners were possibly the first people to view the works. “Nathan was already an established artist, and when he saw the work he knew it was something special,” Kiyoko says. “The colors just grabbed him.” When the Lerners approached Darger to see what he wanted done with the contents of the room, he said they could do whatever they wanted.

After Darger’s death in 1973, Nathan and Kiyoko threw away “two truckloads” of trash, she recalls, but stopped when they found the art. For several years after their discovery, Darger’s shabby room remained relatively untouched. Looking to garner interest in the work, Nathan would bring friends, colleagues, and even psychiatrists to view its contents. “Nathan would show Henry’s work to anyone who would listen,” Kiyoko says. “Anybody. It didn’t have to be artists.”

In 1977, the Hyde Park Art Center put together a Darger show, making it the first gallery to exhibit his work. But in order to display the illustrations, Nathan, in a controversial move, untied the strings that bound them together. While it made the work accessible to the public and helped escalate the popularity of outsider art-works created by artists who are self-taught-many people felt that it divided what was meant to be a single body of work.

Over the years, to secure Darger’s legacy, Nathan spent greater amounts of time with academics, journalists, and gallery owners. “Nathan didn’t promote himself as an artist,” says Mark Pascale, the associate curator of prints and drawings at the Art Institute. “He gained his notoriety from the photographic work he did in the thirties, especially of Maxwell Street, and then he had the design firm, but being the guy who discovered Darger eclipsed everything else.”

The Lerners began selling some of the work in 1979, with pieces bringing around $1,000 each. “Rather than continuing to protect [Darger’s] work, [Nathan] realized he had a marketable commodity,” says Michael Boruch, who was commissioned by Lerner to catalog the contents of the room shortly after Darger’s death. “[Keeping] everything intact fell to the wayside after that.”

The Lerners also donated 30 works to the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland-the premier outsider art museum in the world-four to the Milwaukee Art Museum, and, in Chicago, four to the Museum of Contemporary Art and three to the Art Institute of Chicago. Nathan and Kiyoko moved the remaining 100 or so illustrations, and later all the books, to the air-conditioned first floor.

Interest in the work picked up substantially after 1997, when the American Folk Art Museum mounted a Darger show, and national media celebrated the work.

At that time, it was the museum’s best-attended show.

While Nathan Lerner was open to selling the work, ideally he wanted to keep the collection together. This dilemma has become something of a hot-button issue. Some Dargerphiles have argued that the work should have remained, as it was, on Webster Avenue, while others just hoped that it stayed in Chicago, the artist’s hometown. And although discussions took place, no Chicago museum or gallery pursued it any further-preservation, cost, and relevance to their existing collections being the foremost reasons why.

The Art Institute’s primary concern was that the Dargers were not a good fit for a general collection. “At one point we were in a dialogue with Nathan and the MCA to split the cost of acquiring the pieces,” says Mark Pascale. “It would have been a combo purchase/gift. But there was no clear case that the MCA had the money, and we certainly didn’t either.” Preserving the work also presented a burden. “Our conservation lab was so small before we redid it in 1999 that working on his pieces would have taken the entire lab,” Pascale says. “But we just finished conserving the last one two weeks ago. I’ve been asking for it for ten years.”

For all the interest in Darger’s work, the art posed other issues for the major Chicago museums. Lynne Warren, the curator of the MCA, says, “We’re devoted to contemporary art, not works on paper, which is a whole other bowl of fish.” And Pascale suggests that the complexity of the material’s content made it difficult for the Art Institute to handle. “Everyone asks, Why don’t you put up your Dargers?” Pascale says. “You don’t put anything up you can’t contextualize.

It wasn’t until John MacGregor’s biography of Darger [Henry Darger: In the Realms of the Unreal] came out [in 2002] that we really understood what they meant. Nathan didn’t let many people read the manuscript and you don’t foolhardily put something on a wall and let people grasp at straws.”

For years, the Lerners were in a dialogue with the Milwaukee Art Museum, which houses a large collection of outsider art, but negotiations eventually ceased. And although Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, which was founded in Chicago in 1991, expressed interest, it just didn’t have the resources. “We would have needed at least a million dollars,” says the former director Jeff Cory.

|

Courtesy: Wellspring Media |

| Among the hundreds of works that illustrated Darger’s cataclysmic novel was this carbon transfer, pencil, and watercolor of the Vivian Girls being captured by the Calverinian Boy Scouts, who mistook them for the Glandelinian Girl Scouts (detail). |

Today Henry Darger is the most bankable of outsider artists, with his works bringing up to $150,000. “Since Nathan Lerner’s discovery of Darger’s output, he has always been desirable,” Pascale says. “So much art of the 20th century relied upon collage and montage that his drawings are not so far away from the mainstream of modern art. What made them astounding is their intricate narratives coupled with Darger’s grasp of gesture and context. These are tropes that have been a part of art since people began to make pictures.”

Until last year, Kiyoko continued to sell Darger’s works through galleries and used some of the profits to support a foundation established by the Lerners that provides instruction in fine arts to the mentally ill. Then, after announcing that she would stop selling pieces from the estate, dealers and investors clamored to buy her Dargers before the December 31, 2004, deadline. Andrew Edlin, a New York gallery owner who has sold some of Kiyoko’s Dargers, says that in some cases, prices rose as much as 40 percent in the span of a few months. “I never liked the business side of controlling the estate,” Kiyoko adds. “So I’m happy to have stopped selling them.”

Out of the hundreds of pieces she once owned, Kiyoko is down to about 100 and doesn’t plan to part with them. “I’m happy to loan them to galleries for exhibits-I have 35 at a museum in Europe right now,” she says. “What I have is available for show, but I want the business side to stay calm so I can simplify my life.” But it doesn’t always work that way. “Right when I am about to close this chapter and move, I end up with more activities, not less.”

A few years ago, she was paid $20,000 for a movie option on the Darger story by the Bedford Falls Company-the maker of Thirtysomething, Traffic, and The Last Samurai. Mark Andrus, who wrote As Good as It Gets and Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, has been working on the script. “Not only is there this movie but there is some interest in two more books on Darger and one on Nathan,” Kiyoko says.

For years, the Lerners kept Darger’s old room mostly intact, and Kiyoko even occasionally allowed Dargerphiles to stop by. Mark Pascale remembers visiting the space years ago. “John MacGregor was in town doing research, and Nathan and Kiyoko were out of town, so he invited me and a small group of my art students to see it,” Pascale recalls. “Two of those students I’m still in touch with and they tell me, to this day, that was the most defining moment of their education.”

In 2000, the real-estate developer Michael Lerner, Kiyoko’s stepson, bought the Webster building where Darger had lived and gutted it for remodeling, sweeping clean “the room.” Kiyoko donated the contents to Intuit, which plans to re-create the space, in all of its disheveled glory, at its gallery on Milwaukee Avenue. “Our goal is to create an installation that, although not an exact replication of Darger’s living and working space, will begin to communicate a sense of the environment where he lived and worked for so many years,” says Connie Gibbons, the new director of Intuit. “We want to have the installation completed within the next six months, but there’s still a lot to be done.”

Kiyoko has put her home on the market and plans to move into one of Michael Lerner’s projects in West Town. She hopes to concentrate again on the piano, and her new, one-story, high-ceilinged home includes a 40-by-20-foot living room, which she plans to use as a concert space.

And what will be history’s assessment of the odd genius who lived next door? Mark Pascale may have had a hint. He recalls being visited by a curator from Vienna’s Albertina Museum, which houses one of the largest graphic arts collections in the world. For some reason, Pascale had a Darger displayed in the visitor’s study center. The curator “walked over and said, ‘What is this and who is this master?'” Pascale recalls. “I’ll never forget that.”