|

photography: courtesy of the Marshall family

|

|

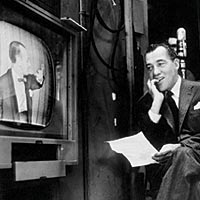

Marshall and his helping hand, Lefty, in 1947. |

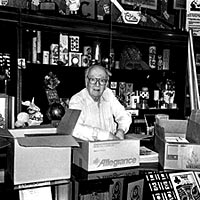

For more than 40 years, Magic, Inc., one of the nation’s oldest and most revered magic emporiums, has occupied a two-story building on the North Side of Chicago, at the corner of Carmen and Lincoln avenues. The structure’s brick-and-slate façade is deceiving; no one would guess that these walls could contain so much. An old-school, family-run operation, Magic, Inc., houses a shop for walk-in trade up front, a petite theatre where magic classes and lectures are held, a print shop that publishes a line of nearly 400 titles, workrooms, scores of nooks and crannies, and a warehouse-like space out back. In an apartment on the second floor of the main building, the incomparable Jay Marshall lived out the last 42 years of his life.

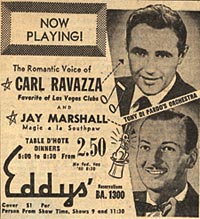

Born on August 29, 1919, too late to participate in the heyday of vaudeville, James Ward Marshall-a.k.a. Jay Marshall, a.k.a. The Great Jasper, a.k.a. the Dean of American Magicians-was a ventriloquist, magician, and comedian whose act took him practically everywhere. He played the Palace Theatre in New York and the London Palladium, stood in for Ed Sullivan as host of the live Sullivan road show, and appeared on nearly every major TV variety hour between the late 1940s and 1970, including 14 appearances on Sullivan’s Sunday night show, Toast of the Town (later The Ed Sullivan Show), on CBS. On almost every stage, Marshall was accompanied by his glove-puppet rabbit, Lefty, whose signature song was a sweet and salty version of “If I Had My Way.”

But while entertainment was Marshall’s business, collecting was his passion. He was quite probably the most voracious collector Chicago has ever known, over the years acquiring literally millions of items, an incredible range of things that tickled his countless interests. He was a gambler, a gourmet, an author, a juggler, a raconteur, and an all-around lover of life. If it interested Marshall-and nearly everything did-he collected it or anything associated with it: circus posters and banners, brass plates, tools (some used, some in never-opened boxes), furniture, broken record players, casino tokens and currency, musical instruments, toys, kitchen gadgets, pocket watches, and books-hundreds of thousands of books.

At the time of his death on May 10, 2005, every square inch of Magic, Inc., was crammed with stuff, some of it great and glorious, but much of it dreadful, down-and-dirty, hadn’t-been-touched-in-30-or-more-years junk.

|

photography: courtesy of the Marshall family

|

| Variety show host Ed Sullivan, who often featured Marshall, watches the magician at work. |

Beginning in the summer following Marshall’s death, my job was to sort through the millions of items he’d stockpiled. David Meyer, a lifelong friend of Marshall’s who was named executor of the magic collection, hired me to help him. My credentials? I’ve sold and collected antique magic miscellany for 12 years, since I was 15; I knew Marshall personally (despite a vast age difference, our friendship grew from when I first saw him perform, in my childhood, through recent years, when we would talk shop weekly, often traveling together to magic conventions); and, thanks to unfettered access granted by Marshall during his lifetime, I knew his collection intimately. Chris and Sandy, Marshall’s grandsons, would be our guides through the labyrinth, offering boxes full of dust masks along the way.

Meyer and I were responsible for the magic-related material only, perhaps 40 percent of Magic, Inc.’s total accumulation (the rest of the stuff, handled by a separate appraiser, was simply the “nonmagic”). Our task was to cull the magic memorabilia from the nonmagic and assess what we found. Some of our charge would be donated to the American Museum of Magic in Marshall, Michigan (no relation), as dictated by Marshall’s will. The balance of the collection-magic and nonmagic alike-would be disposed of via auction, private sale, donations, and the garage sale to end all garage sales, eBay. Sandy and Chris started work in June, a month after Marshall’s death. By the time Meyer and I arrived on the scene in August, the local Salvation Army was refusing further donations from the estate.

We entered the melee on a hot summer afternoon. Even though Meyer and I had peeked into the various rooms at Magic, Inc., many times before and seen the numerous piles and alcoves, it all looked different that day; now we were workers, and the mess was our task. Thousands of books overflowed onto the floor. Hundreds of posters, old and new, pristine and tattered, had been jammed into the rafters. Musical instruments were shoved into closets next to Christmas ornaments, busted telephones, and fast-fading television sets. Ventriloquist dummies-sometimes just sneering, amputated heads-were lying about as if casualties of a puppeteers’ war. The pantry in the upstairs apartment spilled over into the kitchen, aged liquor bottles cascading onto the linoleum. Tiny paths, barely wide enough to walk through, had been cut across some rooms. Lighting everywhere was inadequate, and so was ventilation. A thick layer of choking dust blanketed everything.

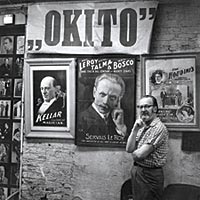

Woven into the patchwork of it all was Marshall’s magic collection, a legendary stockpile renowned worldwide and consulted by those who couldn’t find answers elsewhere. Contents ran the gamut: posters, playbills, photographs, Houdini-owned handcuffs, props used by megastar master magicians of yesteryear (such as Howard Thurston and Harry Kellar), playing cards, autographs, tricks, and stage effects. If it related in some way to magic or magicians, Marshall owned it-and had filed away thousands of facts about it. Teller, the single-named half of the Vegas magic team Penn & Teller, once called Marshall the world of magic’s “British Library and Library of Congress combined.”

|

photography: Sandy Marshall Jr.

|

| In some rooms at Magic, Inc., Marshall left only a narrow trail cutting through the clutter. |

James Edwin Marshall, Jay’s Father, was the treasurer of a bank in Chicopee, Massachusetts, and Edna Marshall, Jay’s mother, was a housewife. There was a love of books and culture in the home, but no propensity for unusual collecting habits or a career in entertainment. Until he dropped out of Bluefield College in Virginia, Marshall appeared to be a fairly average young man-well, almost. His parents indulged his budding interest in conjuring and ventriloquism, taking the future Great Jasper to performances by the day’s leading magicians, including Howard Thurston and Harry Houdini. In his later years, Marshall delighted in recounting the experience of seeing Houdini’s show at age seven. Although the magic portion of the program held his rapt attention, Marshall recalled sleeping through most of the “death-defying escapes.”

Marshall also liked to tell the story of how, at six or seven, he traded his bicycle for a copy of the Tarbell Course in Magic. At that time, Tarbell was the only weekly correspondence course in magic. Later repackaged as a series of eight books, it remains to this day the essential instructional course for budding magicians. In going through Marshall’s things at Magic, Inc., we found perhaps 75 bicycles, most of them broken, along with nearly a dozen copies of the Tarbell Course. Marshall owned everyday items from the life of Harlan Tarbell as well: diaries, correspondence, datebooks, and thousands of canceled checks.

After service in the Pacific in World War II, Marshall-by then a professional entertainer-caught the eye of Mark Leddy, one of New York’s premier theatrical agents and the head talent scout for Ed Sullivan. Marshall’s professional dance card began to fill with prime engagements in nightclubs and hotels, and on stage and television shows across the country and the world. He acted on Broadway in several productions, most notably as a magician in the Elia Kazan–directed Love Life, a show that required him to saw his costar Nanette Fabray in half nightly. In the 1950s, Marshall and Lefty the puppet started working Las Vegas, appearing at various casinos as a trusted emcee and opening act for the singer Pearl Bailey and others.

It was during the fifties that Marshall made the move from Manhattan to Chicago. After divorcing his first wife, Naomi Baker, Marshall began dating and eventually married Frances Ireland, widow of the sleight-of-hand magician Laurie Ireland and proprietor of Ireland’s Magic Shop at 109 North Dearborn Street in Chicago. In the early sixties, Frances and Jay consolidated the business, moved to the city’s North Side, and renamed the enterprise Magic, Inc.

|

photography: Sandy Marshall Jr.

|

| David Meyer (left) and Gabe Fajuri sort through decades of detritus. |

Much of Marshall’s collection was acquired during his working years as he crisscrossed the globe entertaining audiences. In those decades, from the late 1930s until the early 1980s, the concepts of “collectibles” and “antiques” meant something different from what they do today. In those years, most of the magic memorabilia Marshall purchased was not in great demand. Fewer people collected than do today, so prices were lower, and goodies were easier to come by. Houdini lithographs that command $40,000 or more today sold for as little as $5 or $10 in the 1940s. Decades later, in 1993, magicians David Copperfield and Norm Nielsen bought a significant chunk of Marshall’s stash of vintage magic posters for the then-astronomical sum of $250,000. Yet even that sale-in which Marshall unloaded crates full of posters-barely made a dent in his collection.

Meyer and I began our adventure in the second-floor bedroom Marshall had shared with Frances, who passed away in May 2002. We plucked magic-related material from the bookshelves lining the walls, from the closets, and from the dressers, and we covered the bed with our discoveries. In one dresser drawer, we found hundreds of pairs of cuff links, which immediately called to mind a favorite Marshall anecdote and a question: Which were the famous Frank Sinatra cuff links?

Long ago in Las Vegas, during one of his many appearances there, Marshall was winding up his act just ahead of the headliner, the head Rat Packer himself, when the stage manager signaled: Stretch! Sinatra wasn’t ready. Stretch Marshall did and, after six minutes of stalling, he received the high sign. Marshall introduced Sinatra, and the show proceeded as usual. After the curtains fell, Marshall sauntered back to Sinatra’s dressing room. What had happened? “I forgot my cuff links,” Marshall recalled Sinatra saying, “so they had to send someone out to the front of the hotel to get me a pair from the gift shop.” At that, the crooner took off the cuff links and threw them into the wastebasket.

“Are you throwing those away?” Marshall asked.

“Yeah, they’re just a cheap set,” Sinatra responded, according to Marshall’s version of the story.

“Mind if I take them?”

“Go ahead.”

Forever after, Marshall referred to those cuff links as the “pair that Frank Sinatra gave me.”

In the upstairs bedroom at Magic, Inc., we eyed hundreds of sets of old cuff links. None was marked; none seemed more notable than any other. Did we find the Sinatra set? I really don’t know.

|

photograph: Brittney Blair

|

| Marshall’s iconic store |

Could Marshall have found them? Generally, when asked, he was able to track down a specific item. Phone calls and written queries would send him scuttling through the collection. “In the fifties, sixties, and seventies, it was no problem. He knew where it all was,” Meyer told me. Only in Marshall’s later years did treasures disappear in the ever-expanding piles. No one had kept a catalog of the collection, and numerous attempts at organization had failed. The best Marshall did was to group some of his library by subject, and, infrequently, alphabetically-but only the magic books. As he got older, he’d brush off requests, saying, “It’s up there somewhere.”

Books were at the top of Marshall’s list of loves. At the time of his death, best estimates put his library at nearly 250,000 volumes covering countless subjects, from sewing, puppetry, cooking, games, toys, tattoos, gambling, and crime to magic tricks, mathematics, sex, scouting, and humor.

In Marshall’s inner sanctum-a room above the magic shop that held the core of his magic collection-Meyer and I found one of the finer libraries of conjuring literature in private hands. Houdini titles mingled with antiquarian tomes dating as far back as 1584. In a beat-up shirt box reeking of cat urine, Meyer turned up a pristine first edition of Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft, the first book in the English language describing magic tricks, easily worth more than $10,000. The copy had been given to Marshall on his 80th birthday by a friend in New York-and promptly lost. We had been combing the collection for months before Meyer came across it.

Marshall’s stash paired the valuable and the worthless, sometimes in a single item. Mixed in with books on minstrel shows and television, and biographies of fallen Hollywood stars, we found a copy of Father of the Blues, autobiography of the composer and trumpet player W. C. Handy. First editions are available for $20 and up from online bookstores, but in the front of Marshall’s copy, Handy himself had written an inscription: “To Jay Marshall, A pleasure to be

on the same bill with you, W. C. Handy, 7–7–1949.” On the opposite page, in his unmistakable whorly script, Marshall had added the note: “This book was given to me by Mr. Handy when we were on the bill at the Diamond Horseshoe (Billy Rose’s) in New York . . . Jay Marshall.”

|

photography: courtesy of the Marshall family

|

| Although Marshall reportedly traded his bicycle for magic lessons as a child, his collection included more than 75 bikes. |

What led to the obsession with collecting and hoarding? Marshall had a hankering for ownership, what friends and relatives surmise was a constant, pathological need to acquire. He would often trash-pick in alleys, bringing home this broken toy, that tattered piece of furniture, or any one of a thousand other ephemeral, used-up objects, always with the idea that, at some point, he would get back to the stuff: to fix it up, sell it, or learn from it. Sometimes he got around to the task but, more often than not, he didn’t. “Clearly this was something born out of being a Depression- or post-Depression-era child, like a lot of people from his generation,” his grandson Sandy suggests. “And when you’re a collector by nature, and you have all that space to put the stuff in, well, is it any real surprise that he owned and bought as much strange, esoteric stuff as he did?”

Marshall certainly used all the space he had available. Working in a stairwell one afternoon, I found myself trapped between the wall and stacks of books, bound copies of Harper’s Magazine, and decaying suitcases full of magic props. Moth-eaten silk handkerchiefs jutted from holes in 50-year-old shopping bags, and antique magic sets rested against a filing cabinet full of rare playing cards. There was scarcely room to breathe in those close quarters, and when I started moving boxes away from the wall, half of the stuff collapsed on me, plaster raining down like hail. No one had been down that stairwell in years, let alone touched those boxes.

And on the loading dock behind the shop’s little theatre, in a crawlspace no more than three feet high, Sandy and I discovered a huge, weathered theatrical trunk labeled “Brush the Great.” Our combined effort barely budged the box. We broke into it with a crowbar (the ancient locks wouldn’t give, either) and unloaded its contents: odd-looking magic apparatus used by Edwin Brush, a successful magician on the 1920s and ’30s Chautauqua and Lyceum circuits. We lugged the stuff down a rickety ladder before hauling down the empty trunk, which on its own was a struggle to heave.

Like the material in the stairwell, Brush’s trunk had been plunked down in that crawlspace years before and hadn’t been moved since. Marshall’s packrat instinct worked in a set pattern: buy something, absorb its meaning, and-often unintentionally-cast it aside. Trunks like the one we discovered in the crawlspace had grown roots, permanently cementing themselves into the building, blending into the walls, the floors, the scenery, disturbed only now, after Marshall’s death.

|

Seemingly dreary moments sometimes gave way to treasure-filled discoveries. On October 11th, for example, I found myself knee deep in back issues of Woman’s Day and Cat Fancy that had been stacked in the upstairs kitchen. At about 11 in the morning, after two hours of depressing searching and sorting, I struck gold. Three-quarters of the way through a stack, I came upon a nondescript blue plastic tub full of original Houdini ephemera. The tub itself looked like something bought off the shelf at Walgreens, but the Houdini-related papers I found inside were anything but ordinary: handwritten letters from the world’s most famous conjurer; posters; photographs; souvenirs from his performances (“pitch” books sold in theatre lobbies); rare cabinet photographs, with Houdini’s notes on back, of the Davenport Brothers, two famous “spiritualist” entertainers of the 1860s; and a thin diary penned in Houdini’s hand.

Eighty years after Houdini’s death, there is no commodity more valuable to magic collectors than original Houdiniana. Yet Marshall had been content to shuffle the priceless items together with penny-a-pound magazines, burying it all in a long-forgotten corner of his kitchen. At the moment of discovery, I couldn’t help but wonder whether Marshall was looking down and smiling, having known the jackpot was there all along, or if he was as surprised at the find as I was.

Behind the Magic, Inc., building sits a long and large two-story stuccoed warehouse with holes in its roof and windows. We called it the barn. The building had supposedly been a Chicago police stable at one time; then, just prior to Prohibition (or so another rumor has it), the structure was sold to Al Capone and turned into a neighborhood speakeasy. One early fall afternoon, while rooting through the wreckage in the barn, our little crew had nearly hit psychological rock bottom. Our backs ached, and our jeans, reeking of sweat, continually spat out clouds of dirt and grime. By 3 p.m. we hadn’t uncovered anything of significance and didn’t expect our luck to change-until Sandy struck apparent pay dirt. Buried in a mildewed cardboard box was a small cache of Playboy magazines, early ones. At the bottom of the box sat the prize of prizes, Playboy volume one, number one [December 1953], an issue worth as much as $2,000. The centerfold in that inaugural issue? Marilyn Monroe.

|

photograph: courtesy of the Marshall family

|

| Marshall, who as a child saw Harry Houdini perform, poses before posters later sold to magicians David Copperfield and Norm Nielsen. |

Chris and I huddled with Sandy like schoolboys awaiting our first peep. “Turn to the centerfold!” someone said. We quickly paged through the magazine, looking for our day’s salvation in glorious fifties-era color. Instead, we were confounded. Where was Marilyn? We checked the index just to be sure and turned back to the spot. The stumps of several pages stared us down. Some dunderhead had cut out the centerfold. The magazine was worthless.

The discovery of the half-treasures like these characterized many of our days on the job. Finding antiques soiled beyond repair or restoration in the barn was just as common as uncovering broken baubles in the apartment above the magic shop. Meyer told me the situation hadn’t always been that bad. “Things really only ended up that way,” he explained. “It was over the course of the last 30 years of his life that Jay’s collecting habit got out of hand. Fran had always tolerated Jay’s collection and allowed it to be an organized mess. It was always spread out in the apartment and in the barn. It used to be that, despite the piles, things never really were that messy. Jay could always find what he was looking for.”

In December, when I thought all of the magic posters had long been uncovered, I spied an oversize roll of heavy, yellowing paper tucked away in a dreary corner. The bundle was held together at its extremities by ratty pieces of Scotch tape, and it looked of a certain vintage. Curious, I unrolled it. Here was yet another rarity swallowed up by time and space: a billboard advertising the last tour of Houdini’s career, which spanned the 1925-26 theatrical season. The poster stretched some nine feet long, and stood three and a half feet tall. How had we missed such a massive piece in our previous five months on the job?

|

photograph: Mike Sackheim/courtesy of the Marshall family

|

| The magician, circa 1998-99, behind the counter at Magic, Inc. |

Those five months drew to a close on January 20, 2006, when we respectfully submitted our appraisal, and washed our hands clean of the dirt, grime, and legacy one last time. Magic, Inc., continued to lurch forward around us as we completed the job, and continues to do so today, months later. Now owned by the Marshall family, the store still dispenses the stuff of miracle making to miracle mongers the world over.

Meanwhile, per Marshall’s will, a significant portion of the collection was donated to the American Museum of Magic in Marshall, Michigan. The balance continues to be slowly organized, and the nonmagic is in the process of being sold, bit by bit. Some has been cast out into the world via eBay (if browsing, look for the seller named jayandlefty). The fate of the remaining trove has yet to be determined, though hopes are high a substantial auction will be organized in the coming months, thrusting Marshall’s name and his unique aggregation of all things magical back into the spotlight one more time.

Ultimately, for me, the long task of listing and valuing Marshall’s collection wasn’t just about executing an estate job. Sure, in the end, Meyer and I appraised hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of rare magic material. But we were also trying to wrap up Marshall’s 85 years of living, performing, and collecting. Occasionally we would come across worn-out Lefty puppets Marshall had created, used up, and abandoned. One afternoon we uncovered eight or so in a drawer overflowing with miscellaneous magic equipment. The little rabbits had been stowed away for years in darkness, unused and inanimate. Yet during their time on stage, as they sang and smarmed, those puppets had helped Marshall reach out to his audience and make people laugh. Well into his 80s, even when he’d forgotten some of the barbs he and the rabbit used to exchange, Marshall could still connect with his audience. On went the glove, and out the door went reality. It was as if that little rabbit really were singing, talking, and sassing Marshall.

There I stood, staring down at a beat-up bag full of Leftys, separated forever from their maker, their master-mouths painted on, black-button eyes sewn in place, ears detached, limp, and motionless.