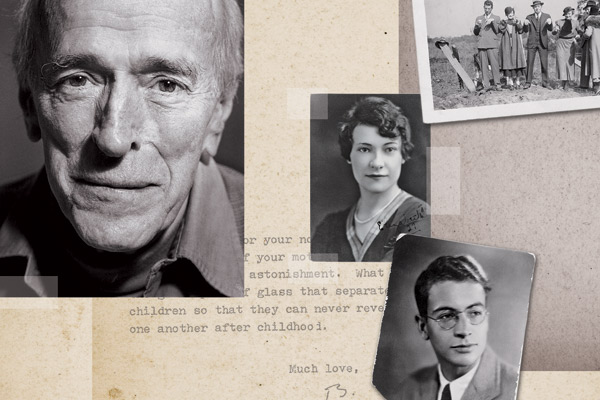

Days gone by: (from left) editor William Maxwell, circa 1992; Elizabeth and Norman Spelman, Maxwell’s college friends and the writer’s parents, circa 1928; with friends at the U. of I. (first from left); (background) a letter from Maxwell to Cornelia Maude Spelman, 1997

|

|

When I was growing up, I’d heard William Maxwell’s name spoken with a respect that Pop reserved for very few people. In the late 1920s, Maxwell and my parents had been part of a literary scene at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, but I had never met him. Although the three of them had fallen out of touch some years after college, Pop had followed Maxwell’s career at The New Yorker, where for 40 years he’d edited the work of writers such as Eudora Welty, John Updike, Vladimir Nabokov, and John Cheever. “For fiction writers, he was the headquarters,” Eudora Welty said of him.

Maxwell, a native of Lincoln, Illinois, was a writer himself—his novels and stories were republished by The Library of America this year. His novel So Long, See You Tomorrow—described as “rare” and “exquisite”—won a National Book Award in 1982. Pop kept Maxwell’s 1934 first novel, Bright Center of Heaven, with this note inside it:

Did you get my letter? Did Harper’s send the book like I told them to? Did Miss Mecker let you review it? What did you say about it? Do you think this is going to be a very Merry Christmas?

Billie Maxwell

* * *

Mother and Pop remained ravenous readers, though their lives were far away from literary circles. A happy memory from my childhood was of the three of us at home in Cincinnati reading, when the older children were not there. I would be in the blue slipcovered wing chair (I was small enough to curl into it, protected by the wings), Pop lying on the sofa, his pipe in his mouth, Mother in her red armchair next to a big round table piled with stacks of books, the oversize turquoise enamel ashtray filling up with crushed Pall Mall cigarettes as the evening wore on.

Pop had seemed proud of his early friendship with Maxwell, and I had understood, although it was never said, that Maxwell had succeeded, and Pop had not; that Maxwell had entered a larger world that Pop and Mother had aspired to enter also, but that, long before my birth, they had given up as impossible for themselves.

I was the youngest of five children, and by the time I came around, Mother and Pop were worn out. Whatever possibilities there had been for my parents’ life belonged to a time before any of us children were born, a time that I pictured as peaceful, free of Pop’s quick irritation, of Mother’s incessant smoker’s cough—when they were young and newly married, just out of college, still pals with Maxwell.

Then, in 1984, ten years after Mother had finally smoked herself to death, when Pop was seriously ill, my husband, Reg, needed to contact Maxwell about an anthology of Chicago writers. I suggested, “Tell him you’re married to Norman and Elizabeth Spelman’s daughter.” Maxwell’s response had been an invitation to tea on our upcoming trip to New York from our home in Evanston.

Reg and I rang his doorbell in a building on the Upper East Side, where Bill and his wife, Emmy, had lived for many years. I was 37 at the time, older by far than he, Pop, and Mother had been when they were friends at the University of Illinois.

The door to his apartment opened. “How you look like your mother and father!” he exclaimed at once. He was a small, dignified man with lively brown eyes. His apartment was light and spacious, filled with books. His spotlessly polished windows framed a view of the East River. “Just cleaned this week,” he told me, smiling, when I commented on them.

We’d arrived a bit too early and felt awkward, and we followed him into the kitchen where he was still making tea. Emmy was away preparing her first exhibition of paintings.

Bill didn’t speak rapidly, allowing more silences than most people do, and providing, I thought, an equivalent to white space on a page of writing. This could have the effect of making someone rush in to fill the quiet. I pressed my lips together. I felt a loyalty to my parents, a responsibility to represent them well, to not say the wrong thing.

Bill turned to me from the cupboard where he was seeking tea cookies. “Your father was a very handsome man, you know, one of the best-looking men on campus.” This surprised me. At that time I was just old enough to understand that my father had lived so much of his life without me as his daughter.

“Was he?” I replied. “Was he a ladies’ man?”

Bill was thoughtful, arranging cookies on a plate. After a moment he turned and said, “No. I don’t think very handsome men have to be. Do you?”

Reg brushed my hand with his, to indicate that he liked the way Bill spoke. The sun was pouring in through the kitchen window on this elderly man, on his white hair and almost translucent skin. Of course he’s old, I thought. He’s my father’s age, 76. Yet Bill’s face retained a puckish charm, and a few minutes later, seated in the living room, as he was pouring our tea, I said, “You have such a young face! I think you were a mischievous boy; perhaps you are still mischievous!” Something about his face and his brown eyes made me think of a boy I had known in school, smaller than I, always ready to be my ally in pranks or games to relieve our boredom, and usually the one to be caught and punished for what I, a proper little girl and therefore unsuspected, had initiated.

Bill regarded me, and for a moment I was afraid I’d been impolite. “You see, it’s odd,” he began after a moment of thought. “One gets older and yet feels the same inside. I find it a shock to see myself in the mirror, to see that I am somehow in this old man’s body.”

Pop had recently said the same thing to me, not long before what had turned out to be a brain tumor had erased such thoughts from his mind, had erased even his lifelong stutter, turning him into a blank, sweet child.

“I enjoy life so much,” Bill continued.

“I have no regrets—except that so many of my friends have died, or are ill. I’m not ready to die. I don’t want to miss the rest of the party.”

“I’m glad!” I said. “You have no sense, then, that the party has ended for you?”

“Oh, no, not at all. I just realize that my body is getting very old,” he replied.

“I’m afraid the party has ended for my father,” I said. “I’m sorry to tell you that he’s very ill right now.”

Bill shook his head and put his teacup down on the table. His hand trembled a little.

“This is so hard for me to believe,” he said. “I remember him only as a young man, you see.”

I thought of a photograph I loved, one taken a few years after my parents had graduated. It showed their first apartment—a “studio,” Mother had called it once, a description I liked because I associated it with artists. Mother is wearing a softly draped dress and a necklace of long beads. Her hair is swept to one side like a 1930s movie star’s. Pop is sitting in a large armchair, a pipe in his mouth, his thick dark hair tousled. He looks like an impossibly young version of the father I knew.

We all sat quietly.

“Your father was a journalist, was he not?” Bill asked me. I understood suddenly why Pop had never renewed contact with his old friend, why he had simply kept him in sight from afar, all these years.

“Oh, no. He would have liked to be a writer, or a college professor. He did write book reviews for The Kansas City Star for a while after college. No, he worked selling dials and nameplates for a manufacturing company.”

My voice or manner must have betrayed my reluctance to reveal my father’s failure. Bill sensed it at once, and was kind. “In a good novel one doesn’t look for a success story,” he said, “but for a story that moves one with its human drama and richness of experience.”

Grateful, I went on. “My parents’ life went off track somewhere. They got bogged down, with the children. Mother, too, wanted a bigger life. She loved reading and wrote a book manuscript herself once, a book about religion, but I don’t know what happened to it.”

“It would be interesting to read it, don’t you think?” he asked me. “You might learn a lot about her, reading her book.”

“Cornelia was hoping you could tell her something about her mother,” Reg said.

“She died ten years ago,” I explained. “And she was sick for many years before that. She ended up in such a sad way.”

Bill nodded and murmured, “I’m so sorry.” He was silent for a moment.

“Well,” he said, “your mother was great fun. She laughed a lot and was very witty. Did you find her witty?”

“Oh, yes,” I said. “She was very funny.” Though later, when I tried to think of funny things she had said, I realized her humor was self-deprecating and ironic, often dark, especially after she was sick. The humor of the prisoner or victim.

Bill continued, “She was brilliantly different and generally admired. More vivid than other girls—the way certain tropical birds are vivid. And while I can’t say she was beautiful—not like you—you’re beautiful, with her eyes and your father’s bones—she was enchanting.”

I smiled at him. I’d heard he was a charming man.

He told me that he and my parents had met at the University of Illinois through a sorority sister of Mother’s. “There was a small group of like-minded people—no more than enough to fill the kitchen of the sorority house—who formed a rather literary group,” Bill said. “In a college largely made up of engineering and agriculture students, the group felt—to me, I mean—aristocratic.

“The girls were all beautiful and saw no reason to hide the fact that they were intelligent. I was half in love with half a dozen of them. The boys were the boys they were dating. I don’t remember any that were not physically attractive. Your father was the most attractive of all. He was not only handsome, he was unpredictable, wildly amusing, and like no one else. Your mother, too.”

I waited, and he added, after a moment, “But I can’t think of any stories about her, really. I’m sorry if I disappoint you.”

He did recall a story about Pop, however. Once, after a tea party at the home of one of Mother’s sorority sisters, the hostess had acted haughty because Pop had used the wrong fork. Later, telling Bill about her reaction, Pop had stuttered, “Y-y-you’d th-th-think I’d t-t-taken out m-m-my p-p-pecker and wh-wh-whammed it on the gr-gr-grand p-p-piano!” We laughed together.

Bill’s tea was excellent, smoky and delicate. I had never tasted tea like it. He was impeccably courteous, and in his presence I wanted to be equally polite, so, although I wished to talk with him longer, after an hour I felt we should go.

He helped me on with my coat. I wished to embrace him, but for some reason I held back.

“I hope I will see you again,” he said to us at the door, and then closed it, extinguishing suddenly the lovely light from his clean windows.

* * *

Photography: (Maxwell) James Hamilton, all others courtesy of Cornelia Maude Spelman

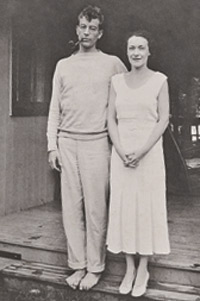

Norman and Elizabeth at home in 1933

Although I visited Bill and Emmy in New York only a few more times, I wrote to him, sharing my thoughts and feelings about Mother and Pop and about my own life, sometimes sending along brief excerpts from Mother’s diaries or letters because I was trying to understand and write about what had happened to that girl he’d described as “vivid.”

With his perfect courtesy, he always replied. I wondered, later, if I’d ended up asking more of him than he’d bargained for when he’d invited us to tea. But he had written to me, “‘Only connect[,]’ Mr. Forster said, and this we have never failed to do,” and as an inscription in one of his books, “For Cornelia Spelman, whom I loved at first sight.”

His affection emboldened me to imagine him as the parent—both father and mother—I wished I’d had, and to turn to him at times for guidance. His two daughters, years after his death, when asked what he was like as a father, spoke of their disappointments. But as Emmy once said to me, during a visit, when I was telling them about my parents’ failings, “Sometimes people make great friends but not great parents.”

Bill was not only a link to Mother’s past, when she had been young and healthy, but, like her, he had experienced the death of a parent when he was a child. His mother had died in January 1919 of the Spanish influenza, when he was ten, and Mother’s father had died of a ruptured appendix in November 1918, when she was seven.

Bill had written about his mother’s death in several of his novels, and when in So Long, See You Tomorrow, he described what it had been like for him, it was as if he was speaking, too, for what Mother must have felt:

The worst that could happen had happened, and the shine went out of everything. [. . .] Between the way things used to be and the way they were now was a void that couldn’t be crossed. [. . .] I hadn’t gone anywhere and nothing was changed, so far as the roof over our heads was concerned, it was just that she was in the cemetery.

When they were friends at the U. of I., Bill didn’t know that Mother, too, had lost a parent. They’d never talked about it. At that time, Mother seemed to be thriving. Bill, however, was not.

In his novel The Folded Leaf, the main character is a university student named Lymie whose mother’s death when he was a child has left him needing “more than the ordinary amount of love.”

Lymie becomes close friends with another student, the only close relationship he’s had since his mother died. But because of a misunderstanding, his friend turns against him. Lymie’s response is to swallow iodine and cut his throat and wrists.

I wrote Bill to ask if this had happened to him. He replied,

My novel is a mixture of autobiography and invention, but the three main characters and their relations to each other are all taken from life, and so are the details of the suicide attempt. I don’t know which is worse, clinical depression or a broken heart, but in my case it was the second. I didn’t so much wish that I was dead, as not want to go on living in a world where the truth (or what I thought was the truth) had no power to make itself believed. I also felt a conscious desire to go where my mother was and to be with her, being still enough of a child to believe, to half believe anyway, that this was possible.

I asked him what my parents had known of this. He replied,

I am sure that your father and mother knew that I had tried to commit suicide but how much else they knew I have no idea. I wore a turtle neck sweater, the only one on campus, until the scar had healed, so I wasn’t exactly inconspicuous. My friends were very supporting, and never mentioned the suicide or asked any questions. When I still had bandages on my throat I went to a dance at the Theta house and the girls saw to it that I had a lovely time.

Though he survived, of course, he continued to suffer. He wrote me that in order to avoid being hurt again by his friend,

I walked about twenty-five feet away and made myself stop loving him. The price for this was that I couldn’t love anyone else for a long long time. I went into analysis because I felt that what was happening to me was what happens to a tree when you cut the center branch out.

Bill’s psychoanalyst in New York was Theodor Reik, who had been a student of Freud’s. During one of my visits with Bill, he told me about the session with Reik in which he had finally returned to his grief at his mother’s death. In So Long, See You Tomorrow, he’d written the same scene he had told me about:

After six months of lying on an analyst’s couch [. . .] I relived that nightly pacing, with my arm around my father’s waist. From the living room into the front hall, then, turning, past the grandfather’s clock and on into the library, and from the library into the living room. From the library into the dining room, where my mother lay in her coffin. Together we stood looking down at her. I meant to say to the fatherly man who was not my father, the elderly Viennese, another exile, with thick glasses and a Germanic accent, I meant to say I couldn’t bear it, but what came out of my mouth was “I can’t bear it.” This statement was followed by a flood of tears such as I hadn’t ever known before, not even in my childhood.

* * *

I saw Bill for the last time in the late spring of 2000. I knew it would be the last. Illness had kept him going in and out of hospitals for months. Although I’d written ahead to ask if he would be well enough to see me, and phoned upon my arrival in New York, still, when I arrived at his door at the appointed time, it wasn’t his wife, Emmy, who opened it but a tall dignified woman, unknown to me—a housekeeper or nurse. Bill had spent the previous night in the hospital, but, she insisted, she would wake him.

I sat down on the sofa and looked around at this room where I’d sat on every visit, gazing out the clean windows. In a few moments I heard a raspy, “Cornelia!” and turned to see Bill, in his plaid flannel bathrobe, on the tall woman’s arm. Beaming at me, he raised both arms for an embrace.

At 91, he looked both ancient and very young. I thought of “Bunny,” the mother’s name for her beloved little boy, her “angel child” in his novel They Came Like Swallows.

We embraced and I helped him to the sofa. His breathing was rapid and shallow, like a puppy’s. I would have only a few minutes with him.

“I want to see you tell your mother’s story,” Bill whispered—he couldn’t speak in his old voice. “It seems it would even it out, somehow, for what happened to her.” I pressed his gnarly hand. I knew he would not be around long enough to know if I’d completed it.

“Bill,” I said, “I’ve been reading the books of Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk.”

He nodded, whispering, “I know of him.”

“And thinking about how when we die we change form,” I said.

After a pause, Bill whispered, “If I could come back in another form, I think it would be as sunshine.” He smiled gently.

“Then, whenever I feel the sun on my face, I will think of you,” I told him. “You will always be with me, Bill. Because of all I have felt for you, and all I have learned from you.”

He smiled. “When you feel the sun, then, you’ll think of me?”

“Yes. I will.”

The tall woman came back into the room to return him to bed. We embraced, and as they walked slowly down the hall away from me, I let myself out the door.

* * *

One fall, several years before he died, Bill had written me, from their summer home in Yorkville Heights,

It’s a gray day, maybe rain tonight, and everywhere a feeling of one thing ending and another beginning. The last of the peaches, and at the vegetable stand all the flowers and baskets of tomatoes removed in order to make room for pumpkins and squashes of the genteel ornamental kind. In about ten days we will be moving back to the city and the cat can no longer ask to be let in and out sixty times a day.

Don’t—or at least I don’t think it is reasonable to—feel sad about the transitoriness of things. What you have had you will always have if you are a rememberer.

Love,

Bill

Photograph: Courtesy of Cornelia Maude Spelman

Comments are closed.