When he opens the front door to his home on the North Shore—a downright unassuming residence, located on a typically suburban lane, standing across the street from an elementary school and a child-friendly park—it’s hard to believe that the man standing there—father, husband, teacher, writer—is a poker addict. Specifically, a junkie to Texas Hold ’Em. But unlike most of the similarly afflicted, James McManus no longer frequents 24-hour casinos or dimly lit Division Street backrooms. These days, almost all his card playing happens in his office, on the computer, about a dozen paces from his family’s rec room, with his wife, Jennifer Arra, working in the kitchen and the sports gear of two of his daughters directly in view.

Over the course of the last decade, McManus, like the game of poker itself, has become somewhat domesticated, at home with all the familiar features of normal suburban life. The most dramatic outward signs of his transformation are the trappings of the unexpected success of 2003’s Positively Fifth Street, a memoir in which McManus chronicles his big win at the 2000 World Series of Poker in Las Vegas, where he finished in fifth place, bringing home $247,760. After years as an acclaimed but scuffling novelist, McManus found himself with a New York Times bestseller and the reputation as a literary expert on poker. The success of the book also meant the chance to pursue his addiction as a career opportunity.

“Playing poker has now become a substantial part of our income, because online sites sponsor certain people, and you get paid to play on those sites: They give you an hourly rate and a rakeback, which is a small portion of the pot, and I get sponsored in tournaments, and if I’m on TV, I get a nice bonus,” he says. Although the legality of earning money from playing online poker is what McManus refers to as “a gray legal area,” with the federal government prosecuting various companies involved in the transfer of money for online games, he pays taxes on his winnings. “It’s no secret,” he says, referring to his new career.

* * *

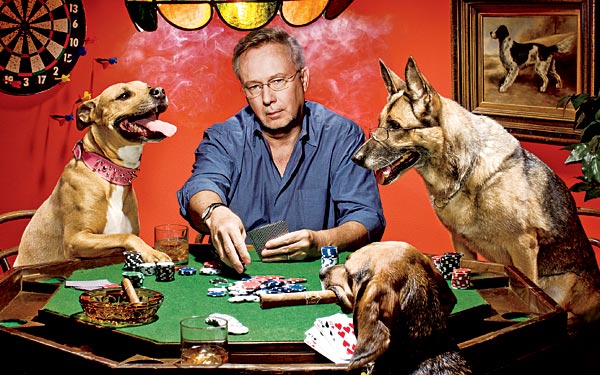

Photograph: Saverio Truglia

Producer: Stephanie Foyer Assistant: Richard Lech Animal casting: Annika Howe Hair and Makeup: Nika Vaughan Special thanks to Courtney Rust (animal talent, from left) Lola/Jeff Jenkins, Petie/Molly Topper, Vala/Jim Morgan

In person, Jim McManus, 58, has both the sharp intensity and the friendly charm of a former competitive athlete who does not like to lose. On an afternoon in midsummer, he is dressed in a T-shirt and running shorts, his hair gray, beard carefully groomed, looking like a dad on the way to his daughter’s soccer game. Nothing about him betrays the fact that he spends most of his day in front of the computer gambling, and, between hands, working on a novel about a poker player, titled The Winter Casino. The office where he writes and plays poker is nothing out of the ordinary, except that it has two bookshelves clearly divided by subject matter, which display his two most salient intellectual interests: fiction and history.

Recently McManus has combined these two loves, fiction’s magnetic draw and history’s preference for context and meaning, to create Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker, a dazzling new nonfiction book that covers the historical and cultural development of poker in the United States with all of the sweep, drama, and comedy of an epic novel. The book lays claim to the idea that poker—as often as it is maligned—is actually more demonstrative of our national character than any other American sport or game, even more than our dearly beloved baseball.

“Ever since the Mayflower carried [the Pilgrims] to Plymouth in 1620, what is often called the American Experiment has lavishly rewarded and punished those who take risks,” McManus writes. “We carry an immigrant-specific genotype, a genetic marker that expresses itself as energetic risk taking, restless curiosity, and competitive self-promotion.”

A prime example of the American character in poker technique is a formerly obscure Illinois state senator: “I’m a pretty good poker player,” Barack Obama once admitted. In Cowboys Full, McManus notes, “Springfield had long been the province of cynical, corrupt backroom operators. So how was this highly educated greenhorn supposed to get along with Chicago ward heelers and conservative downstate farmers? By playing poker with them, of course.” Obama often joined Democrats, Republicans, and lobbyists in a friendly game, where the future commander in chief displayed a preference for “calculated poker, avoiding long-shot draws in favor of patiently waiting for strong starting hands.” More importantly, by McManus’s reckoning, Obama’s poker experience demonstrates his ability to read bluffs. Unlike his predecessor, George W. Bush, Obama saw through Iraq’s empty threat of weapons of mass destruction, asserting in 2002, “I am not opposed to all wars. I’m opposed to dumb wars.” He understood even then that the most dire foreign threats to the United States were in Pakistan and Afghanistan, correctly reading the strength of the players in the game. McManus argues that Obama’s election affirms the nation’s inclination toward a leader who can coolly negotiate the ever-important balance between the slow play and going for the big score.

* * *

Cowboys Full—being published this month by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux—is a tribute to America’s love of those among us who have the heart to gamble big. The new book is something of a gamble for McManus, who has no formal training as a historian, having begun his career as a fiction writer and poet. He readily points out that Cowboys Full (a poker term for a full house with kings) is not a typical historical account, but a story that gives readers the opportunity to delve into the bigger-than-life characters, high-stakes moments, and startling changes that have occurred in poker over the last 200 years.

“I started investigating the history of poker, reading everything I could, and I was shocked that there wasn’t a book like this,” McManus says. “To me, it was so central to the American way of thinking.” He also admits he was “out there flapping by myself, trying to learn to write a history. I was 55 years old, trying to teach myself a new genre. So I forced myself to read books about American history, and it was fantastic. So much of the story of poker is undocumentable, because it doesn’t have the apparatus of typical history.”

Which is exactly what makes Cowboys Full so compelling: It’s a history that follows all the under-the-table trickery, subterfuge, and presidential card games of the nation’s popular imagination, subjects that before had been captured mostly in literature or song. McManus adds, “There’s room in the world for a straight, square history of poker, and this isn’t it. It’s a combination of history and lore, and a hybrid of [the truth and] what’s likely true.”

Take one of the book’s liveliest chapters, “Styles and Technologies of Cheating.” Here McManus details the strategies of various 19th-century riverboat gamblers, who made their way up and down the Mississippi fleecing the unsuspecting and unfortunate. In use at the time were all varieties of cheating instruments, from marked decks to holdout devices “capable of snatching a card from one’s hand and tugging it up that sleeve until the time was right to push it back down again.” Even with these accessories, a suspicious sucker might still call for a fresh deck at every hand, so the cardsharp would sometimes have to mark the new deck right in plain view—perhaps using a needle point welded to a ring to make tiny scratches or holes on high-value cards. Or there were “shiners,” reflective devices such as the surfaces of cigarette cases, snuffboxes, or mirrored rings, angled to reveal the faces of an opponent’s cards. Although extremely popular at the time, these instruments eventually led to the development of various antigambling statutes and to poker’s outlaw cachet.

* * *

This sometimes outlandish history seems to parallel Jim McManus’s lifelong love of the game. His story, like the story of America and the story of poker, begins with the gutsiness of immigrants: “There’s this amazing idea that America introduced to the world, that regular folk could control their own possibilities,” he says. “People today forget that. Throughout most of the world and all of human history, there have been hierarchies. In a poker tournament, everyone starts with the same number of chips. To win, you don’t have to be well-born—you just need to be inclined to take risks. We all know most of us are immigrants, but by studying the [social makeup of Americans], we’ve learned that certain characteristics have become more dominant here in America than in other places. This willingness to leave your homeland and take a risk is what we all have in common.”

McManus’s own great-great-great-grandparents traveled oversea from Ireland and ended up in an Irish community in the Bronx, New York. McManus was born there in 1951. His maternal grandparents, Thomas and Betsy Madden, first taught him how to play poker at the age of nine. Although McManus’s parents were devout Catholics who bristled at the idea of gambling, his grandfather Thomas “worked in the building trades and spent a lot of time at the racetracks, gin halls, and playing card games,” McManus says. “Both of my grandparents had gone through the Great Depression, and so we used to play what they called relief poker, which meant a fraction of every pot would go to a relief fund so that if you went bust, you could go and get money from that. I always thought that said a lot about what they thought of America. It was exactly like FDR.”

In 1958, McManus’s family moved to Joliet. Although he had been raised in the shadow of Yankee Stadium, McManus quickly became a diehard fan of the Chicago White Sox. His interest in poker also changed. By the time he was high-school age, he was playing more seriously and having to hide his winnings. Gone were the days of relief poker; by the mid-1960s he had his cards and buy-in money stashed in a baggie in the gravel of the family’s crawlspace. “If my parents caught me with seven or eight dollars—that was a huge amount of money in 1965—I would have some serious explaining to do.”

While still in high school, McManus began caddying at the Hinsdale Golf Club. “Caddyshacks are hotbeds of poker,” he says. “It was the first job where I made pretty good money, and some of the professional caddies were full-grown men, and they really knew how to play. I got schooled by those guys. One of the guys, his name was Tennessee. The other guy, the caddy master, his name was Doc. I remember one day, I caddied for nine or ten hours and had made 16 dollars or so, and in a few minutes, I had lost all the money I had made, playing poker. I must have been 15 at the time, because my father was picking me up. He said, ‘How did you do?’ and I don’t know why I admitted it, but I told him what happened. My father was sad and disappointed and furious, all at the same time. He was torn between not letting me go back to caddying and knowing it was good money, and so of course I had to swear up and down on a stack of Bibles that I wouldn’t play poker again. Of course, I did.”

By the late sixties, with the war in Vietnam raging, McManus was enrolled as a freshman at Loyola University and was less interested in card games and more interested in the politics of resistance. “We’d take over the campus and throw rocks through windows, thinking that was going to stop the war in Vietnam.” In May 1970, the Loyola campus closed briefly after the shootings at Kent State. McManus took some time off from college and later transferred to the University of Illinois Circle Campus (now UIC) to finish his degree in philosophy. “The next thing I knew, my girlfriend was pregnant, and I was having a kid; so I had a kid before I graduated from college. I don’t recommend it. I was so stuck for cash, trying to support a family on a teaching assistantship, so there was no time, no money, no opportunity to play poker.”

McManus began teaching full-time at the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1980s, and in 1983 A. Alvarez’s nonfiction poker book, The Biggest Game in Town, was published. Reading about the still-developing World Series of Poker—held annually at Binion’s Horseshoe casino in Las Vegas—McManus was mesmerized. “There were these no-limit Hold ’Em games for gigantic sums of money. I would have loved to play in an event like that, but it cost $10,000 to enter, and I was supporting my family on $8,000 a year.” Throughout the eighties, McManus routinely played in small, friendly games “whenever my budget allowed me to play, but I wasn’t making more than going-out-to-dinner money.”

His first marriage ended in 1988, and he began dating Jennifer Arra a year later. Around the same time, he ventured into journalism, which eventually led to the breakthrough book of his career. In 2000, McManus pitched Harper’s magazine a story about a killing in Vegas and how women and computer nerds were beginning to do well in poker tournaments. He admits that his dreams of Vegas and the World Series of Poker factored in. “The real reason I chose that subject is that I wanted a free trip to the tournament with expense money and a check. It was $4,000 for 4,000 words. My second child with Jennifer had just been born. It was a huge amount of money to write an article, going up against my 30-year burn to go play in a tournament out there. And so Jennifer and I had a debate. And then she said okay. So then I had to win the satellite tournament and get very, very off-the-charts lucky. I mean, it intensified my interest in poker by a million times—I’m writing about it for Harper’s, and I’m in this tournament, and all the people I’ve been reading about are at the table across from me. Some confluences of events turn out really, really badly. That was the year I got lucky.” He expanded the Harper’s story into Positively Fifth Street, which spent six weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

Even after the success of Positively Fifth Street, McManus continues to teach writing and literature at the Art Institute, though one of the biggest changes in his life is the income he now earns playing poker online. A beneficiary of the wireless age, he works on various writing assignments while simultaneously playing at fulltilt.com (where he’s listed and pictured as a “Friend of Full Tilt,” along with such other notables as the actor Don Cheadle and Brian Koppelman, who wrote the poker movie Rounders). Much of Cowboys Full was actually composed while playing small-stakes Hold ’Em, a technique he’s continuing for The Winter Casino. “I sit here and work on my book while I’m playing online. I’ll write, and occasionally, depending on what I get dealt, I’ll play the hand. I wait for a huge hand—kings, queens, aces. I get an hourly wage and rakeback, which adds up over the course of a month. Part of my job is to chat with online players. So as soon as I get to my desk in the morning, I put a game on, and then I begin writing. It makes me feel good to kill a bunch of birds with one stone.

“That’s more or less how my day goes—and instead of being in Las Vegas or Indiana, I’m right here with my wife and kids. Usually, it’s 80 or 90 percent of me writing. But I’m very happy to be writing a novel about a guy who’s addicted to playing poker, because I’m addicted. There’s no question about it.”